Stakeholder participation in sustainable development

| Topics: |

Contents

Introduction

Wikipedia describes a stakeholder in seemingly broad terms as: “anyone who has an interest in the project. Project stakeholders are individuals and organizations that are actively involved in the project, or whose interests may be affected as a result of project execution or project completion. They may also exert influence over the project’s objectives and outcomes.” By this definition a ‘stakeholder’ includes those who may live far away from the environs of a sustainable development project, but who may take an interest nonetheless. Thus the construction of a dam in China may have little direct impact on someone living in the Bronx, but if that person takes an interest in the project from reading about it in the media then they automatically become a stakeholder. At first glance this may seem very unconvincing. Why should someone living in the Bronx be a stakeholder for a project thousands of miles away in China just because they take an ‘interest’? Similarly, but perhaps more convincingly, the employees of the company charged with constructing the dam are also stakeholders as they are ‘affected’ in one way or another (via job retention, promotion, salary, completion bonuses etc.). One can reasonably assume that these stakeholders will largely be in favor of the project. There is a further group of people who are stakeholders in such a project; those that commissioned it and have paid the contractor. Included here may be politicians (democratically elected or not), civil servants and parastatals but could also include other companies. These groups have their motives for wanting the project and thus along with the contractor they have a clear interest in its success. But the list of stakeholders is even longer. After all what about those living in the vicinity of the dam and who may well have to be relocated or perhaps those that will find themselves living near to a new shoreline or in the path of a force of water if the dam is breached? Feelings within this group will likely be far more diverse. Some of them may want the project if they see a benefit while others will not. Then there are those that are not charged with the ‘doing’ of the project but will benefit nonetheless from the electricity which is generated even if they live some distance (many miles) away from the dam. Finally there are those who may not gain from the dam in any way but who will feel that it will have a negative impact on the environment. Destruction of unique habitats (Stakeholder participation in sustainable development) perhaps that they regard as a legacy to the world and not just China, and thus leading to serious questions as to whether this is indeed a sustainable development project at all. Included here may be neighboring countries through to international environmental agencies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). With the inclusion of the latter as stakeholders we can indeed go full circle back to the Bronx as many of these international NGOs have memberships that span the globe.

Thus the Wikipedia definition is seemingly broad because a list of those having an interest in a project can also be broad. In the end we are left with familiar ‘trade offs’ within sustainable development and familiar conundrums as to how these ‘trade offs’ should take place (if at all). Which voices should have prominence here and why? Who makes these decisions?

Stakeholder participation within sustainable development has been accepted as not just desirable but a central requirement of any project. The rationale behind this is straightforward and is founded upon two arguments:

- that stakeholders have a fundamental right to be included in deliberations that will have an impact upon their lives. For those that hold this view argument 2 below is almost irrelevant; a right is a right irrespective of whether or not stakeholder involvement helps make any change ‘better’.

- Even if argument 1 is not accepted per se there is the practical argument that listening to the voice of stakeholders and including them within a process of change can help make that change better. This assumes that if people feel that they are included as partners then they will have a heightened sense of wanting it to work, partly because they helped to envision what change is needed but also because they are involved as ‘change agents’ rather than having change imposed upon them. In this sense, the change comes from the ‘inside out’, rather than being imposed from the ‘outside in’. Change is therefore a deeply held product of the community’s self-interest and self-promoting to that community. This type of change might be seen as being viable.

These two arguments are powerful and may provide a space for the conflicting interests of the dam project to be resolved; perhaps not to everyone’s satisfaction but at least to minimize negative impacts and maximize positives. The project could perhaps be made more sustainable.

Problems of stakeholder participation

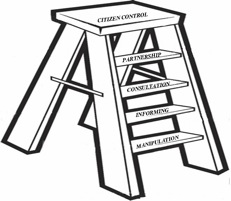

Figure 1. Sherry Arnstein’s ladder of participation. People are manipulated into decisions. People are consulted about what needs to be done but the way in which they are asked is set by external agents and this group also controls the analysis and presentation of the results. People mobilize themselves and initiate actions without the involvement of any external agency, although the latter can help with an enabling environment when approached.

Figure 1. Sherry Arnstein’s ladder of participation. People are manipulated into decisions. People are consulted about what needs to be done but the way in which they are asked is set by external agents and this group also controls the analysis and presentation of the results. People mobilize themselves and initiate actions without the involvement of any external agency, although the latter can help with an enabling environment when approached. While ‘participation’ may be desirable there is a significant leap to be made between theory as espoused above and practice. Just how are people to be included within a participatory process? This may seem like a straightforward question but there are many complex dimensions which are often overlooked. For example, take the following logical steps in sequence:

- Who are the stakeholders of the process? As outlined above in any one intended process of change the population which could be impacted upon could number thousands, if not millions, and may stretch well beyond the immediate ‘place’ where the activities are to be implemented. Within this population there may well be groupings of ‘like-minded’ individuals who share a common agenda (such as the contractor of the dam project and those doing the contracting), but as discussed earlier it is a mistake to assume homogeneity within groups and there can be much diversity in perspective. Hence while the term ‘stakeholder’ is an all too convenient label the identification of those to be included is not as straightforward as it may sound.

- How to represent stakeholders? If the stakeholder groups can be identified then how are they to be represented within the process? It may not be possible to include everyone except in a very limited form (postal survey for example) so it may be necessary to identify a limited number of representatives of the various stakeholder groups. But can all groups be included? What about groups that have internal division? Should sub-groups be included as well? Sociologists often refer to the myth of community - that we often conveniently assume homogeneity within groups in order to make the process of participation easier – but such assumptions can be highly misleading. The answers to these questions will be driven by the inevitable constraints on time and resource, but that does not diminish their importance. For any given process of change which involves stakeholders there can be many perspectives depending upon who is – and who isn’t – included. This is well known, but there has been no research on how different groups of stakeholder can create the ‘many worlds’ of sustainable development; some no doubt more sustainable than others but still valid as a sustainable worldview nonetheless.

- What is the ‘best’ form of participation? If (1) and (2) can be achieved in a way which does provide fair (whatever that may mean) representation of stakeholders then the next question is the form which the process of participation should take? There are many different ways in which stakeholders can be included within a process, and there are many champions of each of these approaches espousing their relative advantages over competitors. The literature is replete with imaginative acronyms for these varied approaches. Each does indeed have its own set of pros and cons, including resources required. There is no space here to provide summaries of all these methods, and the reader is referred to Participation Resource Centre’ hosted at the Institute of Development Studies (IDS) in the United Kingdom for a taste of the diversity. IDS can be thought of as a key influence in the origin of some of the early efforts to develop such methods within a development context. Included here are Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA) and its later derivative Participatory Learning and Action (PLA). All that needs to be stressed here is that which method is ‘best’, if such an adjective can be employed in any meaningful sense, will depend upon context and the expertise of those attempting to facilitate the participation. Bad decisions over which approach to take, and indeed a poor implementation of what should be a viable approach, can greatly reduce and even eliminate the value of including stakeholders even if steps (1) and (2) have been done well.

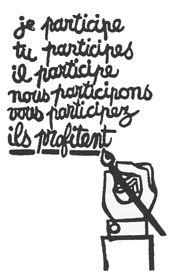

What one gets out of stakeholder participation will depend upon how questions 1 to 3 above have been addressed. If they have been addressed superficially then the result may be pseudo-participation; some stakeholders included but they are not representative and have little (if any) power to make changes to a preconceived project plan. These gradations in participation have long been known and Sherry Arnstein in the United States coined the term ‘ladder of participation’ (Figure 1), with rungs of the ladder representing a spectrum of participation from exploitation at one end to community-led initiatives at the other. A French student poster from the 1960s sets out the same idea in a much simpler form (Figure 2); from stakeholder participation to stakeholder exploitation.

Questions 1 to 3 are certainly challenges for stakeholder participation but there are others.

Sustainability and the bisociate mind

One of the gaps in the ‘participatory’ literature is an understanding of group dynamics in sustainable development. How do the interactions that take place within groups influence the envisioning of sustainable development by those groups? Do more homogeneous groups (assessed in various ways) yield familiar and unimaginative visions of sustainability or do groups need conflict and stress to create more imaginative and challenging visions? There are many such unanswered questions and indeed theories. For example, in this work Koestler sought the origins for and the conditionality required for creativity. His deliberations took him into a variety of areas: laughter and sagacity, visual creation and habitual states, art and science. Early in his book he states the central tenant of his thesis:

“I have coined the term bisociation in order to make a distinction between the routine skills of thinking on a single ‘plane’ as it were, and the creative act, which, as I shall try to show, always operates on more than one plane. The former may be called single minded, the latter double-minded, transitory state of unstable equilibrium where the balance of both emotions and thought is disturbed.” Koestler, 1989

For Koestler creativity and originality arise from the bisociate mind; the mind where opposite or contradictory planes coincide. If this is right then ‘biscoiate groups’ within a stakeholder participatory process could be fertile territory for sustainable development. The opposite type of group, where there is stability and uniformity in position, would generate one-dimensional visions of sustainability that while familiar and perhaps comfortable would not spark new ideas.

Whether Koestler is right or wrong, there remains a potential correlation between the form of stakeholder groups and how those groups would feed insights into a sustainable development project. This is uncharted territory in participatory sustainability but one that needs to be explored nonetheless. How could such an exploration take place?

Exploring participatory sustainability: triple-task

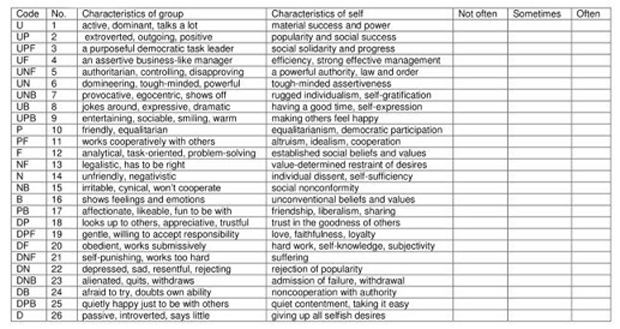

In one sense the analysis of group dynamics is not new. Bridger and others have sought to analyze the dynamics that take place within stakeholder groups, and there is a methodology called Symlog (SYstem for the Multiple Level Observation of Groups) designed specifically for the analysis of small groups. Symlog has a history going back to 1979 when it was first introduced by Bales and Cohen and has since grown to become a popular approach to the analysis of group work and has been applied in a wide variety of contexts. The SYMLOG questionnaire has the structure shown in Table 2. For a group of individuals the answers to the questionnaire generate a table and the results are mapped onto a ‘field diagram’ and interpreted. Based upon this body of work we have developed an approach called ‘Triple-task’ which can be applied within the context of sustainable development. The 3 components of ‘Triple Task’ are:

Task 1. A variant on the participatory methodology described in Bell and Morse and which in turn an extension of ‘Soft Systems Analysis’ developed by Checkland and others as a participatory methodology to be applied within an organizational context. Task 1 seeks to encourage participants to arrive at a shared understanding of ‘what is’ and ‘what can be done’ in any context. In the project summarized here the aim was to arrive at a shared understanding of the use of indicators in sustainable development, but the same process could be applied in any context.

Task 1 involves a 7-step process and a brief summary of the steps is provided as follows. In essence these 7 steps mirror what almost all participatory methods set out to achieve; namely a shared understanding of what is the current situation as well as what are the priorities that need to be addressed and how best to do it:

|

1. Rich Picture mapping |

All participants involved in drawing a Rich Picture of their combined experience of the problem being discussed (e.g. meaning of sustainable development or perhaps the context which a project is meant to address). The RP represents a shared understanding of the group. |

|

2. Tasks and Issues |

Participants draw out major issues or problems with their shared understanding of the sustainable development context. Included here are things that might be done to improve the situation |

|

3. Key Challenges |

Participants put together tasks and issues in four or five ‘Key Challenges’ (priorities) out of the many that may exist and provide them with catchy titles to indicate their main meaning. |

|

4. Defining transformation |

The group identifies what is required to address the challenges set out in step 3? |

|

5. Vision of Change |

What is the vision of change the group would like to see? |

|

6. Scenarios for the future |

The group identifies Who needs to do What and When in order to achieve the vision of change. |

|

7. Review and reflect |

A self and group analysis of the groups progress (See Task 3 below). |

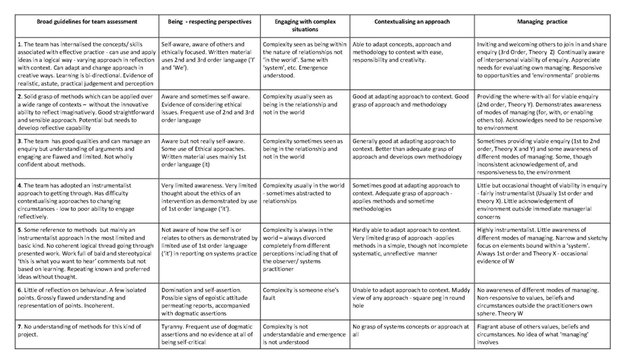

Table 1. Criteria which can be employed within an externally-led BECM analysis of groups. The rows represent a gradation from excellent group function (row 1) and interaction to dysfunctional (row 7). Columns provide a set of characteristics that can be looked for when placing a group into an appropriate row.

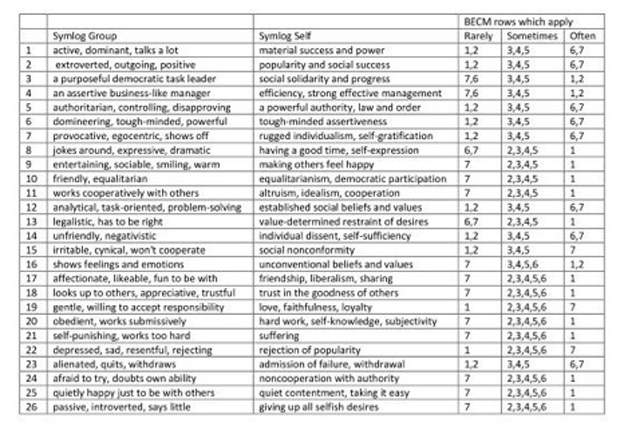

Table 1. Criteria which can be employed within an externally-led BECM analysis of groups. The rows represent a gradation from excellent group function (row 1) and interaction to dysfunctional (row 7). Columns provide a set of characteristics that can be looked for when placing a group into an appropriate row. Task 2. An external analysis of group interactions arrived at by facilitators who are not within groups. This is a reflective review of the manner in which the group(s) work using Action Learning Cycle (including the Being, Engaging, Contextualizing and Managing or BECM matrix. The criteria employed in the BECM assessment are shown in Table 1. There are 7 rows with each row representing a scale from ‘positive’ group behavior (score 1) to ‘negative’ (score 7). The columns list the criteria which can be employed to place groups within respective rows. Even though criteria are set out this is nonetheless a subjective assessment based upon an ‘external’ observation of group interactions. However, stakeholders can be interviewed afterwards to see whether they can confirm (or not) the researchers placement of the group within the BECM matrix.

Task 3. A self-analysis by individuals within groups of themselves and their group interaction using the Symlog approach. The Symlog questions at the individual and group level help to generate the categories within the BECM matrix (Table 2).

The result of putting these 3 tasks together is a triangulation including a group process along with an analysis as to why groups may have arrived at the outputs they did. Table 3 for example shows how the BECM criteria can be theoretically correlated with Symlog results. Thus it is possible to derive explanatory factors behind the visions created by the groups. To date most participatory approaches have only dealt with Task 1 – the arrival at the shared understanding without a formal analysis as to how the groups managed to arrive at that understanding. Triple-Task takes that much further.

What ‘Triple Task’ or any such analysis of participation doesn’t do, of course, is make any valued judgment about whether any vision is better than any other. This is, of course, an important and recurring issue in the broader context of sustainable development. Much of the contestation that takes place tends to revolve around conflict over which vision(s) for the future is best and who has responsibility for achieving it, and this in turn often comes down to which vision is best for whom? Sustainable development is simply not defined in anything like enough detail to significantly narrow down the range of worldviews that it can theoretically encompass, and arguably it should not be defined in this way. After all, the world is a diverse place. Any participatory method such as Triple Task should not seek to work with one normative definition or hold any up as being ‘better’ but instead embraces diversity of worldview and tries to understand the rules which produce and orientate it. This can be a difficult position for sustainable development experts to take; to stand back and allow others a real voice. But there is no point in doing participation unless this occurs.

Summary

Stakeholder participation is very much in vogue within sustainable development projects. There is logic to this popularity, both in terms of a basic human right and also as a way of helping to make projects ‘better’ for those meant to benefit. But unfortunately it is also a convenient ‘catchall’ to add respectability and confidence that what is being done is the ‘right’ thing. The term ‘stakeholder participation’ is much easier said than done and there are many pitfalls in the practice which can lead to ‘stakeholder exploitation’. There are also significant gaps in our knowledge about how stakeholder groups can generate new ideas and insights that can potentially be very useful within sustainable development projects.

There is indeed much still to do.

References

- Arnstein, SR (1969). A Ladder of Citizen Participation. Journal of the American Planning Association 35(4), 216-224.

- Bell, S. (2008) Systemic Approaches to Managing Across the Gap in the Public Sector: Results of an action research programme. Systemic Practice and Action Research 21(3), 227 - 240.

- Bell, S. and Morse, S. (2003) Measuring Sustainability: Learning from doing. London. Earthscan.

- Bell, S. and Morse, S. (2008) Sustainability Indicators: Measuring the immeasurable. London, Earthscan.

- Bales, R. F. and Cohen, S. P. (1979) SYMLOG: A system for the multiple level observation of groups. New York: Free Press.

- Checkland, P. (1981) Systems Thinking, Systems Practice. Chichester. Wiley.

- Koestler, A. (1989) The Act of Creation. London, Penguin.

Further reading

- Wikipedia definitions for ‘stakeholder’

- More on Symlog

- There are many websites on participation but the ‘Participation Resource Centre’ hosted at the Institute of Development Studies in the UK is an excellent starting point.