Southern Africa and forests and woodlands

Contents

- 1 Introduction Table 1: Forest and woodland cover in Southern Africa 2000 (Source: FAO) Southern Africa has a range of forest and woodland types that provide key goods-and-services and are a valuable source of export earnings and revenue as well as for local livelihoods. These forests and woodland types include tropical rain forests found in parts of Angola and the Congo basin; afromontane forests found in pockets in the high altitude and high rainfall areas of Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe; mangrove forests found on the coastline of Angola, Mozambique, Tanzania and South Africa; Zambezi teak forests found in the western parts of Zimbabwe and Zambia, extending into northern Botswana, north-eastern Namibia and parts of south-eastern Angola; Miombo woodlands found north of the Limpopo River; Mopane woodlands found in the dry and low-lying parts of Angola, Botswana, Mozambique, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe; and the Cape Floristic Centre forests found along the south-western coastline and located entirely within South Africa. (Southern Africa and forests and woodlands)

- 2 Overview of resources Forests and woodlands cover about 221.94 million hectare (ha) or 32.5 percent of the total land area. As shown in Table 1 there is considerable variation in vegetation cover across countries. Lesotho, Namibia and South Africa are the least forested countries with less than 30 percent forest cover. At 56 percent vegetation cover, Angola is the most densely forested country in the sub-region. Of the total forested area in the region, 2.5 million ha was under forest plantations in 2001. This represents a 9 percent growth in plantations when compared with the 2.3 million ha of plantations in 1992. Lesotho has experienced considerable growth in the extent of its forests, doubling the area under forest plantation from 7,000 ha in 2000 to 14,000 ha in 2003. As Table 7 shows, South Africa has the largest extent of forest plantations followed by Swaziland, Zimbabwe, Angola, Tanzania and Malawi. However, the total land under forests declined from 1990 to 2000. Over this period, South Africa experienced a deforestation (Southern Africa and forests and woodlands) rate of 0.1 percent per year, Angola, Mozambique and Tanzania 0.2 percent, Botswana and Namibia 0.9 percent, Swaziland 1.2 percent, Zimbabwe 1.5 percent, and Zambia and Malawi 2.4 percent.

- 3 Endowments and opportunities

- 4 Threats to the opportunities

- 5 Strategies to improve opportunities

- 6 Future challenges and recommendations

- 7 Further reading

Introduction Table 1: Forest and woodland cover in Southern Africa 2000 (Source: FAO) Southern Africa has a range of forest and woodland types that provide key goods-and-services and are a valuable source of export earnings and revenue as well as for local livelihoods. These forests and woodland types include tropical rain forests found in parts of Angola and the Congo basin; afromontane forests found in pockets in the high altitude and high rainfall areas of Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe; mangrove forests found on the coastline of Angola, Mozambique, Tanzania and South Africa; Zambezi teak forests found in the western parts of Zimbabwe and Zambia, extending into northern Botswana, north-eastern Namibia and parts of south-eastern Angola; Miombo woodlands found north of the Limpopo River; Mopane woodlands found in the dry and low-lying parts of Angola, Botswana, Mozambique, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe; and the Cape Floristic Centre forests found along the south-western coastline and located entirely within South Africa. (Southern Africa and forests and woodlands)

Overview of resources Forests and woodlands cover about 221.94 million hectare (ha) or 32.5 percent of the total land area. As shown in Table 1 there is considerable variation in vegetation cover across countries. Lesotho, Namibia and South Africa are the least forested countries with less than 30 percent forest cover. At 56 percent vegetation cover, Angola is the most densely forested country in the sub-region. Of the total forested area in the region, 2.5 million ha was under forest plantations in 2001. This represents a 9 percent growth in plantations when compared with the 2.3 million ha of plantations in 1992. Lesotho has experienced considerable growth in the extent of its forests, doubling the area under forest plantation from 7,000 ha in 2000 to 14,000 ha in 2003. As Table 7 shows, South Africa has the largest extent of forest plantations followed by Swaziland, Zimbabwe, Angola, Tanzania and Malawi. However, the total land under forests declined from 1990 to 2000. Over this period, South Africa experienced a deforestation (Southern Africa and forests and woodlands) rate of 0.1 percent per year, Angola, Mozambique and Tanzania 0.2 percent, Botswana and Namibia 0.9 percent, Swaziland 1.2 percent, Zimbabwe 1.5 percent, and Zambia and Malawi 2.4 percent.

Endowments and opportunities

Forests and woodlands provide essential materials for local consumption, trade and export. The significance of the timber industry is shown in Table 2. Other functions of forests and woodlands include environmental and cultural services. Forests and woodlands are often important sacred and burial sites. With the exception of South Africa, fuelwood is the primary source of energy. Fuelwood consumption continues to increase; in 2000 total fuelwood consumption was estimated at 178 million m3. About 87 percent of the roundwood production in the region is used as fuelwood. The situation is likely to continue since fuelwood remains the most reliable, affordable and accessible source of energy for poor households. However, several countries are investing in the development of renewable solar and wind energy.

In addition to timber, wood-processing and paper production, forests and woodlands provide a wide range of goods-and-services for subsistence and trade including medicinal plants, fruits, exudates, bee products, insects, roots, thatch grass, forage and mushrooms. As a result of expanding international trade in medicinal plants and indigenous fruit, it is important to develop a legal regime for intellectual and property rights which recognizes and respects local people’s interests, and ensures equitable benefit sharing.

Threats to the opportunities

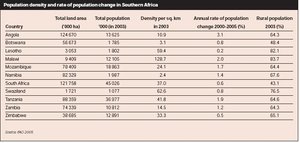

Some countries in Southern Africa have very fastgrowing populations, and face the challenge of needing to increase food supplies to meet demand for food. Population change is shown in Table 3. This has necessitated the opening up of large areas of forests and woodlands for agricultural production. Between 1990 and 2000, forest cover fell from 380 to 357 million ha. The increase in urbanization and the pressure on land in peri-urban areas for cultivation also present new challenges.

Fire plays an important role in determining the distribution and composition of some vegetation types. It is responsible for the widespread occurrence of grasslands in Southern Africa. Observations from Mbeya, Tanzania, indicate that burning encourages growth of grass and prevents regeneration of woody plants.

Strategies to improve opportunities

Many countries have made major investments in rural forestation programmes with a bias in indigenous species and agroforestry. Further, in attempting to reduce deforestation caused by the overharvesting of commercial indigenous timber, Botswana and Zambia have restricted logging of timber for commercial purposes while Zimbabwe has imposed a ban on the export of unprocessed indigenous timber.

All SADC Member States signed the SADC Forestry Protocol, and three countries had ratified it by 2004. The specific objectives of the Protocol include the promotion of the development, conservation, sustainable management and utilization of all types of forests and trees; the promotion of trade in forest products in order to alleviate poverty and generate economic opportunities; and the achievement of the effective protection of the environment and the safeguard of the interests of both present and future generations.

There is also growing pressure to certify the origin of wood products to show that they are obtained from sustainably managed areas as a response to growing awareness of the negative environmental and social impacts of deforestation. Certification has only been done in some exotic timber plantations where considerable value addition is done to timber products. The entire 974,000 ha of certified plantations in Africa are, however, mostly found in Southern Africa, with the highest proportions being in South Africa followed by Swaziland and then Zimbabwe.

Many governments acknowledge the potential value and opportunity that forests and woodlands bring to improving livelihoods, particularly in rural areas, and are increasingly recognizing that secure tenure is an important aspect of this. Several countries have initiated reforms to support local communities, including the empowerment of local bodies and communities to manage communal resources through a process of decentralization and devolution of administrative powers and responsibilities.

Future challenges and recommendations

The people of Southern Africa will continue to be highly dependent on forests and woodlands for the foreseeable future. Despite their aspirations, many people may even become more dependent on natural resources as poverty and population increase. The region is therefore challenged to realize the multiple benefits accruing from forests and woodlands, in addition to crop production which converts forests to cultivable land. The multiple uses of forests include commercial tiber production. Certification can serve as a check on management practices. However, the process of certification is expensive, and this challenges the region to add value to forest and woodland products and increase their revenue.

The commercialization of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) raises the issue of benefit sharing at the community, national and international levels. Legislation that regulates access to forest resources by outside parties is poorly developed. This deficiency may result in biopiracy, especially of medicinal plants, which are highly profitable on the global market and about which traditional healers have a lot of knowledge.

It must be noted that existing information on forests and woodlands is often outdated and incomplete. This is partly because most of it is obtained from secondary sources. For instance, no forestry inventory has been done in Angola since independence in 1975. Therefore, an important challenge is to develop and update its forest and woodlands database, and to develop effective monitoring and evaluation systems.

Further reading

- Chenje, M. (ed. 2000). State of the Environment Zambezi Basin 2000. Southern African Development Community / IUCN – The World Conservation Union / Zambezi River Authority / Southern African Research and Documentation Centre, Maseru/Lusaka/Harare.

- FAO, 2003. Forestry Outlook Study for Africa African Development Bank, European Commission and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

- FAO, 2005. State of the World’s Forests 2005. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome

- McCullum, H., 2000. Biodiversity of Indigenous Forests and Woodlands in Southern Africa. Southern African research and Documentation Centre, Harare.

- SADC, 2002. The Southern African Development Community Protocol on Forestry. Southern African Development Community, Luanda.

- UNEP, 2002. African Environment Outlook: Past, Present and Future Perspectives. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi.

- UNEP, 2006. Africa Environment Outlook 2

|

|

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |