Somali Coastal Current large marine ecosystem

Contents

- 1 Introduction Location of Somali Coast Current LME. (Source: NOAA (Somali Coastal Current large marine ecosystem) )

- 2 Productivity

- 3 Fish and Fisheries

- 4 Pollution and Ecosystem Health

- 5 Socio-economic Conditions

- 6 Governance

- 7 References

- 7.1 Articles and LME Volumes Alexander, Lewis M. 1998. Somali Current Large Marine Ecosystem and Related Issues. In K. Sherman, E.N. Okemwa, and M.J. Ntiba, eds. Large Marine Ecosystems of the Indian Ocean: Assessment, Sustainability, and Management. (Oxford: Blackwell Science). pp.327-333. ISBN: 0632043180 (Somali Coastal Current large marine ecosystem) . * Baars, M. A.; Schalk, P. H. and Veldhuis, M. J. W. "Seasonal Fluctuations in Plankton Biomass and Productivity in the Ecosystems of the Somali Current, Gulf of Aden, and Southern Red Sea", In K. Sherman, E.N. Okemwa, and M.J. Ntiba, eds. Large Marine Ecosystems of the Indian Ocean: Assessment, Sustainability, and Management (Oxford: Blackwell Science). pp. 143-174. ISBN: 0632043180. * Bakun, Andrew; Roy, Claude; and Lluch-Cota, Salvador. 1998. "Coastal Upwelling and Other Processes Regulating Ecosystem Productivity and Fish Production in the Western Indian Ocean," In K. Sherman, E.N. Okemwa, and M.J. Ntiba, eds. Large Marine Ecosystems of the Indian Ocean: Assessment, Sustainability, and Management. (Oxford: Blackwell Science). pp. 103-141. ISBN: 0632043180. * Dwivedi, S.N. and A.K. Choubey, 1998. Indian Ocean Large Marine Ecosystems: need for national and regional framework for conservation and sustainable development. In: K Sherman, E.N. Okemwa, and M.J. Ntiba, eds. Large Marine Ecosystems of the Indian Ocean: Assessment, Sustainability, and Management. (Oxford: Blackwell Science). 361-368. ISBN: 0632043180. * FAO, 2003. Trends in oceanic captures and clustering of large marine ecosystems—2 studies based on the FAO capture database. FAO fisheries technical paper 435. 71 pages. * Mailu, GM, 1998. Implications of Agenda 21 of the UNCED on marine resources in East Africa with particular reference to Kenya and Tanzania. In K. Sherman, E.N. Okemwa, and M.J. Ntiba, eds. Large Marine Ecosystems of the Indian Ocean: Assessment, Sustainability, and Management (Oxford: Blackwell Science). 313-326. ISBN: 0632043180. * Muhando, C. and NS Jiddawi, 1998. Fisheries resources of Zanzibar: problems and recommendations. In: K. Sherman, E.N. Okemwa, and M.J. Ntiba, eds. Large Marine Ecosystems of the Indian Ocean: Assessment, Sustainability, and Management. (Oxford: Blackwell Science). 247-254. ISBN: 0632043180. * Nguta, C. Mweu. 1998. An overview of the status of marine pollution in the East African region. In K. Sherman, E.N. Okemwa, and M.J. Ntiba, eds. Large Marine Ecosystems of the Indian Ocean: Assessment, Sustainability, and Management. (Blackwell Science). 61-71. ISBN: 0632043180. * Okemwa, Ezekiel, 1998. "Application of the Large Marine Ecosystem Concept to the Somali Current". In K Sherman, E.N. Okemwa, and M.J. Ntiba, eds. Large Marine Ecosystems of the Indian Ocean: Assessment, Sustainability, and Management. (Oxford: Blackwell Science) pp.73-99. ISBN: 0632043180. * Pollock, D.E., 1998. Spiny lobsters in the Indian Ocean: speciation in relation to oceanographic ecosystems. In K. Sherman, E.N. Okemwa, and M.J. Ntiba, eds. Large Marine Ecosystems of the Indian Ocean: Assessment, Sustainability, and Management (Oxford: Blackwell Science). 215-222. ISBN: 0632043180. * Raal, P.A. and L. Barwell, 1998. Application of integrated environmental management toward solving the problems affecting the Tana River Delta and its linkage with the Somali Current ecosystem. In K. Sherman, E.N. Okemwa, and M.J. Ntiba, eds. Large Marine Ecosystems of the Indian Ocean: Assessment, Sustainability, and Management (Oxford: Blackwell Science). 343-352. ISBN: 0632043180. * Weru, S.D.M., 1998. Marine conservation areas in Kenya. In K. Sherman, E.N. Okemwa, and M.J. Ntiba, eds. Large Marine Ecosystems of the Indian Ocean: Assessment, Sustainability, and Management (Oxford: Blackwell Science). 353-360. ISBN: 0632043180.

- 7.2 Other References

- 7.3 Citation

Introduction Location of Somali Coast Current LME. (Source: NOAA (Somali Coastal Current large marine ecosystem) )

This Large Marine Ecosystem (LME) is characterized by its tropical climate. It is a monsoon-influenced Indian Ocean ecosystem, which lies off the northeastern margin of the African continent. It includes the continental shelf areas of Yemen, Somalia, Kenya and Tanzania. In the summer, its dominant oceanographic feature is the strong, northerly flowing Somali Current. In the winter the Somali Current reverses its flow. Book chapters and articles pertaining to this LME include Alexander, 1998, Baars et al, 1998, Bakun et al, 1998, Dwivedi and Choubey, 1998, Mailu, 1998, Nguta, 1998, Okemwa, 1998, Pollock, 1998 and Weru, 1998. The Global International Waters Assessment (GIWA) has a Somali Coastal Current page.

Productivity

With the summer monsoon (from April to October), the South Equatorial Current flows northward, forming the Somali Current. It penetrates deep into the water column, causing strong upwelling. During the winter monsoon, the Somali Current is weaker. It reverses its flow and joins the South Equatorial Current off of Northern Kenya (see Nguta, 1998). For more information on the LME’s tectonic structure, ocean currents, tides and climate, see Okemwa, 1998. For a map of prevailing winds in this LME, see Mailu, 1998. For more information on coastal upwelling as it relates to ecosystem productivity and fish production, see Bakun et al, 1998. The Somali Coastal Current LME is considered a Class II, moderately productive (150-300 grams of Carbon per square meter per year (gC/m2-yr)) ecosystem based on SeaWiFS global primary productivity estimates. For seasonal fluctuations in plankton biomass and productivity, see Baars et al, 1998. Very little is documented about the abundance of zooplankton in this LME, which makes it difficult to determine which species of copepods, euphausiids, salps, and doliolids dominate the shelf (see Okemwa, 1998). Coral reefs, mangroves, seagrass beds, beaches, and estuaries serve as a home, breeding ground, or nursery for many species (see Okemwa, 1998). Cetacea and other endangered (IUCN Red List Criteria for Endangered) species depend on these ecosystems. The coastal waters represent a unique biotic region and contains diverse and endemic plants and animals. For information on Somalia’s coral reefs, see Pilcher and Krupp, 2000. For more information on coral reefs in this LME, click on Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network (GCRMN), and ReefBase project.

Fish and Fisheries

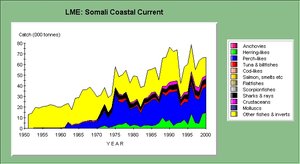

(Source: NOAA)

(Source: NOAA) The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) 10-year trend shows a decrease from 60,000 tons in 1990 to about 50,000 tons in 1999, with several peaks and troughs in fisheries catch (see FAO, 2003, appendix figure 19). The bulk of the catch (40%) consists of miscellaneous coastal fishes. Small pelagic species include herrings, sardines and anchovies. Pelagic shrimp are fished by Tanzania and Kenya (see Okemwa, 1998). For a description of fishery resources, see Mailu, 1998. The fisheries are predominantly small, traditional and artisanal. Statistics are reported with poor species breakdown. For more information on the spiny lobster in the Indian Ocean, see Pollock, 1998. For fisheries in Zanzibar (part of Tanzania), see Muhando and Jiddawi, 1998. Fishing activity follows a strong seasonal pattern with the lowest effort in June-August, and peak landings from October to January. The Global International Waters Assessment (GIWA) has issued a matrix that ranks LMEs in the area of fisheries. GIWA characterizes the Somali Current LME as severely impacted in the area of overexploitation of fisheries, excessive bycatch and discards, and destructive fishing practices. Fishermen use handlines, traps, spear guns and gill and seine nets. These fisheries impacts are increasing. The University of British Columbia Fisheries Center has detailed fish catch statistics for this LME. Compiled FAO data is is available by clicking on the graph below.

Pollution and Ecosystem Health

(Source: NOAA)

(Source: NOAA) The countries surrounding the Somali Current LME are experiencing significant and widespread environmental degradation as a result of increasing pressures from human population growth and expansion and intensification of land use (see Okemwa, 1998). Large quantities of fertilizer and pesticides are used in agricultural areas that gradually make their way to the sea as runoff. There is stress and degradation of coastal habitats. Coral reefs, mangroves, beaches, estuaries, and seagrass beds are impacted by sedimentation, dynamiting for fish, the removal of coral souvenirs by tourists, the dredging of harbors, coastal industry, hazardous waste and garbage, speedboats, damaging fishing methods such as trawling and oil pollution (see Okemwa, 1998). For more information on endangered (IUCN Red List Criteria for Endangered) marine species (marine turtles, marine mammals), pollution (sewage, agricultural wastes, industrial wastes and siltation, and ocean-based pollution), and on the design of a monitoring strategy, see Okemwa, 1998. Siltation has increased each year as a result of human activities on land such as mining, clearing for agriculture, industry, urban growth and dredging. This is changing the coastal configurations of river deltas. Oil pollution from ships is caused by spills, ballast discharges, bilge washings, offshore oil exploration, and refinery effluents. This type of pollution is prevalent in the Somali Coastal Current LME because it encompasses major tanker routes for oil shipped to the Persian Gulf. The Global International Waters Assessment (GIWA) has issued a matrix that ranks LMEs according to the destruction and degradation of [[ecosystem]s], habitat and community modification, pollution and global change. GIWA characterizes the Somali Current LME as severely impacted economically and socially in the area of habitat and community modification, and severely impacted in the area of fisheries (see above). These impacts are increasing. Nguta, 1998, presents an overview of the status of marine pollution in East Africa. A number of marine parks and reserves have been established. For information on marine conservation areas in Kenya, see Weru, 1998.

Socio-economic Conditions

Subsistence fishermen, with their dependents and those involved in fish distribution and processing, are at the core of the small, traditional, and artisanal fishing industry, although Kenya and Tanzania are developing industrial fleets. Artisanal fishing is concentrated in the coastal lagoons. The income of traditional fishing families is below the national average and frequently below the poverty line. The growing industrial fleet creates tension with the traditional fishermen by taking more of already overexploited coastal resources and destroying their stationary gear. The traditional fishermen must also compete with long-distance foreign fleets, from the Republic of Korea, Japan, France, Taiwan and Spain (see Okemwa, 1998). Reliable economic data is scarce, especially as regards Somalia, hampered by continuing internal political strife. The biodiversity resources of this LME are of critical environmental and economic value. A managed expansion of fisheries (Fisheries and aquaculture) could provide food security to the human populations living in the coastal areas. The LME’s varied [[ecosystem]s] (coastal lagoons, coral reefs, mangroves, seagrass beds and estuaries) could serve as sites for aquaculture projects. The diverse and endemic plants and animals are important to the further development of tourism and marine wildlife utilization (see Weru, 1998, for marine conservation areas in Kenya). For a description of non-living resources (oil and gas, salt, harbors and beaches), see Mailu, 1998.

Governance

(Source: NOAA)

(Source: NOAA) There is a need to implement monitoring efforts on spatial and temporal scales, to identify the ecosystem effects of climate change, and to discover the major driving forces causing large scale changes in biomass yields. The coral reefs of the LME require a form of regional collaboration in coral reef management. A research assessment and management program needs to be implemented but a major management constraint is the political situation in Somalia, where civil war and factional fighting have taken place for the last decade. As a result, the country cannot manage the national economy nor seriously address issues of marine ecosystem management. National legislation in Somalia is at this time virtually non-existent. Countries such as Kenya and Tanzania are in a different situation. They have a long history of strong interest in the preservation and conservation of their wildlife resources and critical habitats through the creation of parks. Kenya has a major Marine and Fisheries Research Institute. For a study of the Tana River Delta’s linkage with the Somali Current ecosystem and attempts at integrated environmental management, see Raal and Barwell,1998. Mailu, 1998, examines the implications of UNCED and Agenda 21 on the management of marine resources in Kenya and Tanzania. The countries bordering the Somali Current LME and the Agulhas Current LME are planning for a Global Environment Facility-supported LME assessment and management project. For the latest information on intergovernmental agreements, action programs, projects, and other Somali Current LME initiatives, click on the GIWA Somali Coastal Current page.

References

Articles and LME Volumes Alexander, Lewis M. 1998. Somali Current Large Marine Ecosystem and Related Issues. In K. Sherman, E.N. Okemwa, and M.J. Ntiba, eds. Large Marine Ecosystems of the Indian Ocean: Assessment, Sustainability, and Management. (Oxford: Blackwell Science). pp.327-333. ISBN: 0632043180 (Somali Coastal Current large marine ecosystem) . * Baars, M. A.; Schalk, P. H. and Veldhuis, M. J. W. "Seasonal Fluctuations in Plankton Biomass and Productivity in the Ecosystems of the Somali Current, Gulf of Aden, and Southern Red Sea", In K. Sherman, E.N. Okemwa, and M.J. Ntiba, eds. Large Marine Ecosystems of the Indian Ocean: Assessment, Sustainability, and Management (Oxford: Blackwell Science). pp. 143-174. ISBN: 0632043180. * Bakun, Andrew; Roy, Claude; and Lluch-Cota, Salvador. 1998. "Coastal Upwelling and Other Processes Regulating Ecosystem Productivity and Fish Production in the Western Indian Ocean," In K. Sherman, E.N. Okemwa, and M.J. Ntiba, eds. Large Marine Ecosystems of the Indian Ocean: Assessment, Sustainability, and Management. (Oxford: Blackwell Science). pp. 103-141. ISBN: 0632043180. * Dwivedi, S.N. and A.K. Choubey, 1998. Indian Ocean Large Marine Ecosystems: need for national and regional framework for conservation and sustainable development. In: K Sherman, E.N. Okemwa, and M.J. Ntiba, eds. Large Marine Ecosystems of the Indian Ocean: Assessment, Sustainability, and Management. (Oxford: Blackwell Science). 361-368. ISBN: 0632043180. * FAO, 2003. Trends in oceanic captures and clustering of large marine ecosystems—2 studies based on the FAO capture database. FAO fisheries technical paper 435. 71 pages. * Mailu, GM, 1998. Implications of Agenda 21 of the UNCED on marine resources in East Africa with particular reference to Kenya and Tanzania. In K. Sherman, E.N. Okemwa, and M.J. Ntiba, eds. Large Marine Ecosystems of the Indian Ocean: Assessment, Sustainability, and Management (Oxford: Blackwell Science). 313-326. ISBN: 0632043180. * Muhando, C. and NS Jiddawi, 1998. Fisheries resources of Zanzibar: problems and recommendations. In: K. Sherman, E.N. Okemwa, and M.J. Ntiba, eds. Large Marine Ecosystems of the Indian Ocean: Assessment, Sustainability, and Management. (Oxford: Blackwell Science). 247-254. ISBN: 0632043180. * Nguta, C. Mweu. 1998. An overview of the status of marine pollution in the East African region. In K. Sherman, E.N. Okemwa, and M.J. Ntiba, eds. Large Marine Ecosystems of the Indian Ocean: Assessment, Sustainability, and Management. (Blackwell Science). 61-71. ISBN: 0632043180. * Okemwa, Ezekiel, 1998. "Application of the Large Marine Ecosystem Concept to the Somali Current". In K Sherman, E.N. Okemwa, and M.J. Ntiba, eds. Large Marine Ecosystems of the Indian Ocean: Assessment, Sustainability, and Management. (Oxford: Blackwell Science) pp.73-99. ISBN: 0632043180. * Pollock, D.E., 1998. Spiny lobsters in the Indian Ocean: speciation in relation to oceanographic ecosystems. In K. Sherman, E.N. Okemwa, and M.J. Ntiba, eds. Large Marine Ecosystems of the Indian Ocean: Assessment, Sustainability, and Management (Oxford: Blackwell Science). 215-222. ISBN: 0632043180. * Raal, P.A. and L. Barwell, 1998. Application of integrated environmental management toward solving the problems affecting the Tana River Delta and its linkage with the Somali Current ecosystem. In K. Sherman, E.N. Okemwa, and M.J. Ntiba, eds. Large Marine Ecosystems of the Indian Ocean: Assessment, Sustainability, and Management (Oxford: Blackwell Science). 343-352. ISBN: 0632043180. * Weru, S.D.M., 1998. Marine conservation areas in Kenya. In K. Sherman, E.N. Okemwa, and M.J. Ntiba, eds. Large Marine Ecosystems of the Indian Ocean: Assessment, Sustainability, and Management (Oxford: Blackwell Science). 353-360. ISBN: 0632043180.

Other References

- Bryceson, I., T.F. de Souza, I. Jehangeer, M.A.K. Ngoile and P. Wynter, 1990. State of the marine environment in the Eastern African Region. UNEP Regional Seas Reports and Studies No. 113. Nairobi, Kenya: 46 pp.

- McClanahan, T.R., 1994. Kenyan coral reef lagoon fish: effects of fishing, substrate complexity, and sea urchins. Coral Reefs 13(4): 231-241.

- McClanahan, T.R. and J.C. Mutere, 1994. Coral and sea urchin assemblage structure and interrelationships in Kenyan reef lagoons. Hydrobiologia 286:109-124.

- McClanahan, T.R. and D. Obura, 1994. Status of Kenyan coral reefs. In: Ginsburg, R.N. (compiler), Proceedings of the Colloquium on Global Aspects of Coral Reefs: Health, Hazards and History, 1993: 392-396. McClanahan, T.I. and S.H. Shafir. 1990. Causes and consequences of sea urchin abundance and diversity in Kenyan coral reef lagoons. Oecologia 83: 210-218. ISBN: 0520232550.

- Muthiga, N. 1995. Coral reefs of Kenya: A review of past and current research activities and priorities. Background paper presented at the ICLARM Workshop, Cairo, Egypt (22-27 September, 1995), 12 pp.

- Pilcher, N. and Krupp, F., 2000, The Status of Coral Reefs in Somalia. Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network (GCRMN).

- R.V. Salm, N. Muthiga and C. Muhando, on coral reefs. ICRI homepage.

- Smith, S.L. 1982. "The Northwestern Indian Ocean During the Monsoons of 1979: Distribution, Abundance, and Feeding of Zooplankton." Deep Sea Resources. 29: 1331-1353.

- Spalding, M.D., C. Ravilious and E.P. Green , 2001. World Atlas of Coral Reefs. Prepared at the UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre. University of California Press, Berkeley, USA. At ReefBase, under Kenya.

- United Nations Environmental Programme. 1985. "Management and Conservation of Renewable Marine Resources in the East Africa Region." UNEP Regional Seas Reports and Studies. No. 66, Nairobi, Kenya.

- United Nations Environmental Programme. 1982. "Pollution and the Marine Environment in the Indian Ocean." UNEP Regional Seas Reports and Studies. No. 13, Nairobi, Kenya.

- Waldichuk, M. 1976. "Global Marine Pollution: An Overview." Paris: UNESCO.

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |