Socio-cultural conditions, health status, and demography in the Arctic

This is Section 15.2 of the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment.

Lead Authors: Jim Berner, Christopher Furgal; Contributing Authors: Peter Bjerregaard, Mike Bradley, Tine Curtis, Edward De Fabo, Juhani Hassi, William Keatinge, Siv Kvernmo, Simo Nayha, Hannu Rintamaki, John Warren.

Social conditions and lifestyles among indigenous populations vary widely throughout the Arctic. Many indigenous peoples rely on the food that they hunt and harvest from the land and sea, as it provides for much of their nutritional intake as well as being a critical component of their cultural identity, and in many cases, their local informal economy[1]. Members of the urban population, of whom many are of European descent, have lives that are to some extent indistinguishable from those of their kinfolk in Europe or North America, although the arctic climate still determines much of their daily life and is an underlying condition for infrastructure and transport.

Contents

Socio-cultural conditions and health status (15.2.1)

Living conditions are changing throughout the Arctic for indigenous as well as non-indigenous residents as a consequence of the change from an economy based on hunting to modern wage earning[2].The following description of social change in Greenland (Bjerregaard and Curtis, 2002) is similar to that in many other circumpolar regions. The shift from a traditional Inuit community to a modern society started at the beginning of the 20th century when fishing began to replace the hunting of marine mammals as the main source of livelihood. This was accompanied by population movement from a large number of small villages to larger – although still small by many standards – population centers, and by the gradual supplement of the traditional subsistence economy by a cash economy. By the end of the Second World War, however, Greenland still had a relatively isolated and traditional society where most people lived in small villages and subsisted on small-scale hunting and fishing activities. During the latter half of the 20th century unprecedented changes occurred in Greenland resulting in a very modern society thoroughly integrated in global political and economic systems. Fishing and the associated processing industry are the basis of the present economy but at a very advanced level with ocean-going fishing vessels existing alongside smaller crafts and some fishing from the ice. Subsistence hunting and fishing are still widespread but are increasingly becoming a leisure activity. Daily connections by air to Denmark now exist, and even small villages have telephone service and internet access. Supermarkets contain products such as fresh mangos and papayas, as well as a range of European meats, dairy, and vegetable products, and frozen Greenlandic fish and seal meat.

The influence of such changes on physical health and everyday life are obvious; positive changes include vastly improved housing conditions, a stable supply of food and increased access to western goods, and decreased mortality and morbidity from infectious diseases including tuberculosis. However, societal change and modernization have also brought a number of social and mental health problems as well as increasing prevalence of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular diseases and diabetes[3]. Children have been brought up with values that were useful for hunters and hunters’ wives living in small communities: independence, self-reliance, non-interference with other people’s lives, and physical strength. As adolescents and adults they have had to cope with life in much larger and more densely populated communities, in a world that rewards formal education, language skills, and discussion instead of action.The majority of individuals have adjusted to the new situation but for some the burden has been a significant challenge. In some cases, these changes have been associated with historical changes in climatic conditions. The relationship between climate and settlement in Greenland illustrates the complexity of these changes in arctic communities (see Box 15.1).

|

Box 15.1. Climate change impacts on settlement in Greenland In the early 20th century, climate warming resulted in Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) appearing in great shoals off the west coast of Greenland. Cod fishing became a source of cash income for the Greenlanders and the traditional society based on hunting of seals and whales began to make way for a modern fishing society and cash economy. The population of Greenland concentrated in fewer and larger towns and the number of villages decreased. This development was intensified after the Second World War due to deliberate concentration of the population in towns with schools, health care, and shops. Fishing was planned to be the major source of revenue for the Greenland society. In the 1960s, however, climate cooling together with overfishing resulted in the disappearance of cod from the west coast of Greenland[4] (see also Section 15.5.5.3 (Socio-cultural conditions, health status, and demography in the Arctic)). In the 1960s, large numbers of shrimp were detected in Disko Bay. Over the course of a few years, the village of Qasigiannguit with a population of only 343 in 1955 developed into a lively town centered on the shrimp factory. During the 1990s, the shrimp disappeared from the coastal waters. Large sea-going vessels now fish and process the shrimp far from the coast and the factory has closed. People have started moving from the town. In 1982 when the population was at its maximum there were 1800 inhabitants; in 2000 the population of Qasigiannguit was only 1400. The unemployment rate is among the highest in Greenland: 14.4% compared to 7.1% in the towns in general. The examples show how climate change can influence the occurrence of commercially important species and how the disappearance of a species can have negative impacts on socio-economic conditions within a local community. Many Inuit communities are particularly vulnerable to changes in species availability because they often rely on the availability of only one or a few species. |

Over the last 50 years, the population of most arctic regions has dramatically increased. Much of this increase is due to a reduction in infant mortality and mortality from infectious diseases, particularly tuberculosis and the vaccine preventable diseases of childhood. Also, safe water supplies, sewage disposal, development of rural hospitals, and in some regions, community-based medical providers, have contributed to improved care and access to care for injuries and illness. All regions have greatly improved transportation infrastructure, resulting in the availability of western food items, tobacco, and alcohol on a scale not previously possible. Plus, in many arctic regions communications technology has made western culture visible in even the most remote settlements. Arctic indigenous residents are, in most regions, encouraged to become permanent residents in fixed locations, to facilitate the provision of services and economic opportunities. This has eliminated the historic practice of families and groups of families to move, intact, when climate or other environmental change made a region unable to sustain them. Also, there are often few products or services that many small communities can contribute to the overall economy, such that survival often depends on a complex web of government-funded economic support, combined with primarily service-based employment in schools, sanitation facilities, and transportation infrastructure. The establishment of fixed village locations has also affected subsistence activities.

Indigenous culture is under stress from competing western culture, and subsistence activities are affected by climate change and concerns about the contamination of traditional food resources by contaminants, both from local sources and from long-range sources transported to the Arctic via ocean and atmospheric currents. Zoonotic diseases (animal diseases that can be passed to humans) and parasitic diseases are also associated with some traditional food species and traditional food preparation methods (e.g., trichinosis or botulism). Assessments of food safety have resulted in the collection of information on micronutrients and anthropogenic chemicals and have often resulted in the release of confusing or conflicting messages to rural residents[6]. As a result, erosion of cultural support, a decrease in traditional activities, and substitution of western foods for traditional foods are becoming more important as the causes of morbidity and mortality among arctic populations such that, in some respects, they now more closely resemble western populations.

Historically, there was little heart disease, cancer, obesity, or diabetes in circumpolar populations. Major causes of mortality were infectious diseases, especially tuberculosis, pneumonia, and injury. Life expectancy was short, and infant mortality was high[7]. However, for the reasons discussed in this section much has now changed. The section Population structure and health statistics (below) presents the current population structure, birth rates, infant mortality, and causes of adult mortality for the countries with arctic residents. Arctic regions of the Russian Federation have few comparable data but there is no reason to believe that this region does not also have similar serious health problems as seen elsewhere.

Many technological advances have made subsistence hunting safer, such as modern protective clothing, Global Positioning System (GPS) devices, radio, cellular telephones, and weather forecasts. Hunting efficiency has also improved dramatically through the use of modern firearms and improved transportation, such as boats, snowmobiles, all terrain vehicles, and aircraft.These advances have the potential to erode traditional knowledge and skills, which could increase risk. For instance, loss of traditional knowledge of short-term weather changes and ice thickness could result in injury or death.

Population structure and health statistics (15.2.2)

Some regions of the Arctic have a different population structure compared to that of more temperate regions of the same country.This is true for the indigenous rural arctic populations; including Alaska Natives, Canadian Arctic indigenous groups, Inuit, and Greenland Inuit.

The populations of the Northwest Territories (NWT, including Nunavut) and the Yukon (which are predominantly indigenous), as well as Alaska Natives and Greenland residents (who are 90% Inuit), have a greater percentage of children and a smaller percentage of older people than in the Nordic countries (Fig. 15.1[12]).These three groups represent the majority of rural arctic residents for whom comparable health data exists. All these groups typically reside in very small communities (of around 50 to 5000 inhabitants), in remote regions, and with traditional foods comprising a significant part of the diet.

The health of arctic populations can be determined from a range of health status indicators, including life expectancy at birth, birth rate, infant mortality, population mortality, and age-adjusted causes of death.

Life expectancy (15.2.2.1)

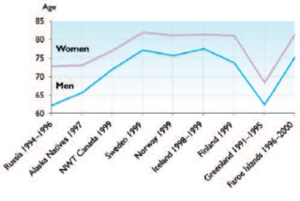

Life expectancy in arctic populations has improved owing to a wide variety of changes in social conditions and lifestyles. A significant contributor to improved life expectancy is decreased infant mortality. Alaska Natives, NWT residents, and Greenland residents generally have lower life expectancies than residents in the Nordic countries and on average, life expectancy is lower for indigenous populations (Fig. 15.2[13]).

Birth rate (15.2.2.2)

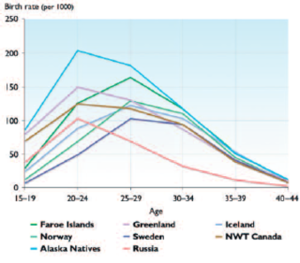

Alaska Natives, NWT residents, and Greenland residents have higher birth rates than residents in the Nordic countries (Fig. 15.3). This reflects the greater proportion of children in these populations.

Infant mortality (15.2.2.3)

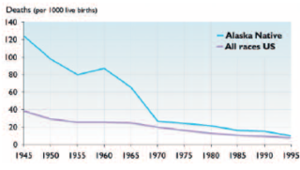

Infant mortality has decreased considerably since around 1950 for Alaska Natives (Fig. 15.4). Despite the improvement the overall infant mortality rates for indigenous arctic residents in Alaska and Greenland remain higher than for all races infant mortality rates in the United States and Canada. Infant mortality rates are lowest in the Nordic countries.

Common causes of death (15.2.2.4)

Differences also exist in the most common causes of death based on death certificate data. To account for differences in population age structure (see Fig. 15.1) the mortality rates were adjusted to those for a standardized population structure; although the standard population structure used for the Nordic countries is slightly different to that for Canada and the United States. Figure 15.5 compares death rates for a range of conditions in indigenous populations (or largely indigenous in the case of the NWT) and the American and European populations. It is evident that Alaska Natives and Greenland residents have much higher mortality rates for injury and suicide. Mortality rates for heart disease and cancer are now similar in arctic indigenous populations and in relation to overall rates for the United States, Canada, and Northern European countries.

Chapter 15: Human Health

15.1. Introduction (Socio-cultural conditions, health status, and demography in the Arctic)

15.2. Socio-cultural conditions, health status, and demography

15.3. Potential impacts of direct mechanisms of climate change on human health

15.4. Potential impacts of indirect mechanisms of climate change on human health

15.5. Environmental change and social, cultural, and mental health

15.6. Developing a community response to climate change and health

15.7. Conclusions and recommendations (Socio-cultural conditions, health status, and demography in the Arctic) (Socio-cultural conditions, health status, and demography in the Arctic)

References

Citation

Committee, I. (2012). Socio-cultural conditions, health status, and demography in the Arctic. Retrieved from http://editors.eol.org/eoearth/wiki/Socio-cultural_conditions,_health_status,_and_demography_in_the_Arctic- ↑ Duhaime, G. (ed), 2002. Sustainable Food Security in the Arctic: State of the Knowledge. Canadian Circumpolar Institute, University of Alberta, Occasional Publication Series No. 52.

- ↑ AMAP, 2003. AMAP Assessment 2002: Human Health in the Arctic. Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme, Oslo.

- ↑ Bjerregaard, P. and K.T.Young, 1998.The Circumpolar Inuit – Health of a Population in Transition. Munksgaard, Copenhagen.

- ↑ Hamilton, L.C., B.C. Brown and R.O. Rasmussen, 2003.West Greenland’s cod-to-shrimp transition: local dimensions of climatic change. Arctic, 56(3P):271–282.

- ↑ WHO, 2000.World Health Organization International Statistical Database. <a class="external free" href="http://www.who.int/whosis" rel="nofollow" title="http://www.who.int/whosis">http://www.who.int/whosis</a>

- ↑ AMAP, 2003, Op. cit.;-- CACAR II, 2003. Canadian Arctic Contaminants Assessment Report II, vols: Human Health, Biotic Environment, Abiotic Environment, Knowledge in Action, Highlights. Indian and Northern Affairs, Canada.

- ↑ Bjerregaard and Young, 1998, Op. cit.

- ↑ IHS, 1999b. Regional differences in Indian health, 1998–99. Indian Health Service, Rockville, Maryland.;-- WHO, 2000, Op. cit.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ AMAP, 2002. Arctic Pollution 2002: Persistent Organic Pollutants, Heavy Metals, Radioactivity, Human Health, Changing Pathways. Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme, Oslo. xii+112pp.

- ↑ ; Statistics Canada, 2003