Mixed economies in the Arctic

This is Section 12.2.2 of the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment

Lead Author: Mark Nuttall; Contributing Authors: Fikret Berkes, Bruce Forbes, Gary Kofinas,Tatiana Vlassova, George Wenzel

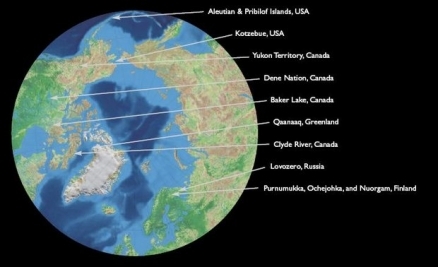

In indigenous communities in the Arctic today, households are economic units within villages, settlements, and small towns characterized by a blend of formal economies (e.g., commercial harvesting of fish and other animals, oil and mineral extraction, forestry, and tourism) and informal economies (e.g., harvesting renewable resources from land and sea). The ability to carry out harvesting activities is not just dependent on the availability of animals, but on the availability of cash, as the technologies of modern harvesting activities are extremely expensive in remote and distant arctic communities. Throughout the Arctic, many indigenous communities (whether they are predominantly seal hunting communities in northern Greenland or Canada, fishing communities in Norway, or reindeer herding societies in Siberia) are increasingly characterized by pluri-activity in that cash is generated through full-time or part-time paid work, seasonal labor, craft-making, commercial fishing, or other pursuits such as involvement in tourism that support and supplement renewable resource harvesting activities.

In mixed economies, half or more of household incomes may come from wage employment, simple commodity production, or from government transfer payments[1]. Increasing reliance on other economic activities does not mean that production of food for the household has declined in importance. Hunting, herding, gathering, and fishing activities are mainly aimed at satisfying the important social, cultural, and nutritional needs, as well as the economic needs, of families, households, and communities (see Bodenhorn[2] for northern Alaska, Hovelsrud-Broda[3] for East Greenland, and Wenzel[4] for eastern Baffin Island).

Research points to the continued importance of harvesting activities despite a growing proportion of the population of indigenous communities not being directly involved in harvesting (e.g., [5]). Purchased foodstuffs supplement diets composed mainly of wildlife resources[6] and individuals and households that do not have the means or ability to hunt often have regular access to country foods through local distribution channels and networks of sharing (see the case study of Inuit sharing patterns in Nunavut in Section 12.3.2 (Mixed economies in the Arctic)).

Nor has money diminished subsistence-oriented production as a central feature of life in the Arctic – indeed cash has made the continuation of hunting, herding, and gathering possible in some cases, rather than contributing to its decline[7]. In parts of the Arctic commercial and subsistence uses of country foods are intrinsically linked. In Alaskan villages fish for the household are often taken during commercial fishing trips, the profits from which are often invested in new equipment for subsistence pursuits[8].

Cash is often used to buy equipment for procuring food from harvesting activities (e.g., boats, rifles, snow-machines). Cash also meets demands for a rising standard of living: to purchase oil to heat homes, to buy consumer goods, or to travel beyond the community. While food procured from renewable resource harvesting continues to provide arctic peoples with important nutritional, socio-economic, and cultural benefits, finding ways to earn money is a major concern in many arctic communities[9]. The interdependence between formal and informal economic sectors, as well as the seasonal and irregular nature of wage generating activities (such as tourism) means that families and households are often faced with a major problem in ensuring a regular cash flow. For example, Callaway et al.[10] demonstrated that the ability to carry out harvesting activities in Alaska – and thus the quality of life in rural communities – is linked to the state’s economic and political environments.

The impacts of climate change on formal economic activities will also have implications for renewable resource harvesting activities. In Alaska, recent climate change has increased the cost and risk of subsistence pursuits. On the coast of northern Alaska, where the ice pack has retreated a significantly greater distance from land, North Slope hunters have to cross a greater expanse of open water to reach hunting grounds. The increased time and distance added to a hunting trip adds to the cost and risk of accessing marine mammal resources. Fuel and maintenance costs are greater because of the longer distance to travel, which also decreases the use and expectancy of the technology used (boats, engines, rifles). For safety reasons, boats with larger engines are required, adding strain to limited budgets[11].

The economic value of traditional/country food is emphasized by the level of food insecurity common among indigenous peoples. In a major dietary survey in Yukon First Nation communities, 39% of respondents reported having insufficient resources to purchase all the food they would need from the store if traditional food was not available; the average weekly "northern food basket" was priced at Can$164 in communities, compared to Can$128 in Whitehorse[12]. The Nunavut case study ([[Section 12.3.2 (Mixed economies in the Arctic)]2]) illustrates the problems hunters face in gaining access to money. While hunting produces large amounts of high quality food – the Government of Nunavut estimates that it would cost approximately Can$ 35,000,000 to replace this harvest production – as the case study illustrates, virtually none of this traditional wealth can be converted into the money needed to purchase, operate, and maintain the equipment hunters use. Abandoning hunting for imported food would be less healthy and immensely costly.

Chapter 12. Hunting, herding, fishing, and gathering: indigenous peoples and renewable resource use in the Arctic

12.1 Introduction (Mixed economies in the Arctic)

12.2 Present uses of living marine and terrestrial resources

12.2.1 Indigenous peoples, animals, and climate in the Arctic

12.2.2 Mixed economies

12.2.3 Renewable resource use, resource development, and global processes

12.2.4 Renewable resource use and climate change

12.2.5 Responding to climate change

12.3 Understanding climate change impacts through case studies

12.3.1 Canadian Western Arctic: the Inuvialuit of Sachs Harbour

12.3.2 Canadian Inuit in Nunavut

12.3.3 The Yamal Nenets of northwest Siberia

12.3.4 Indigenous peoples of the Russian North

12.3.5 Indigenous caribou systems of North America

References

Citation

Committee, I. (2012). Mixed economies in the Arctic. Retrieved from http://editors.eol.org/eoearth/wiki/Mixed_economies_in_the_Arctic- ↑ Caulfield, R., 2000. The political economy of renewable resource harvesting in the Arctic. In: M. Nuttall and T. V. Callaghan (eds.). The Arctic: Environment, People, Policy. Harwood Academic Press.–Langdon, S.J., 1986. Contradictions in Alaskan Native economy and society. In: S. Langdon (ed.). Contemporary Alaskan Native Economics, pp. 29–46. University Press of America.–Weinstein, M.S., 1996. The Ross River Dena: a Yukon Aboriginal Economy Ottawa. Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples.

- ↑ Bodenhorn, B., 2000. It’s good to know who your relatives are but we are taught to share with everybody: shares and sharing among Inupiaq households. In: G. W. Wenzel, G. Hovelsrud-Broda and N. Kishigami (eds.). The Social Economy of Sharing: Resource Allocation and Modern Hunter-Gatherers, pp. 27–60. Senri Ethnological Series. National Museum of Ethnology, Osaka.

- ↑ Hovelsrud-Broda, G., 2000. Sharing, transfers transactions and the concept of generalized reciprocity. In: G. W. Wenzel, G. Hovelsrud-Broda, N. Kishigami (eds.). The Social Economy of Sharing: Resource Allocation and Modern Hunter-Gatherers, pp. 61–85. Senri Ethnological Series. National Museum of Ethnology, Osaka.

- ↑ Wenzel, G. W., 2000. Sharing, money, and modern Inuit subsistence: obligation and reciprocity at Clyde River, Nunavut. In: G. W. Wenzel, G. Hovelsrud-Broda and N. Kishigami (eds.). The Social Economy of Sharing: Resource Allocation and Modern Hunter-Gatherers, pp. 61–85. Senri Ethnological Series. National Museum of Ethnology, Osaka.

- ↑ Usher, P. 2002. Inuvialuit use of the Beaufort Sea and its resources, 1960–2000. Arctic, 55(1):18–28.

- ↑ Callaway, D., 1995. Resource use in rural Alaskan communities. In: D.L. Peterson and D.R. Johnson (eds.). Human Ecology and Climate Change: People and Resources in the Far North. Taylor and Francis.–Nuttall, M., 1992. Arctic Homeland: Kinship, Community and Development in Northwest Greenland. University of Toronto Press.

- ↑ Kruse, J., 1991. Alaska Inupiat subsistence and wage employment patterns: understanding individual choice. Human Organization, 50(4):317–326.–Nuttall, M., 1992. Arctic Homeland: Kinship, Community and Development in Northwest Greenland. University of Toronto Press.–Wenzel, G. W., 1991. Animal Rights, Human Rights: Ecology, Economy and Ideology in the Canadian Arctic. University of Toronto Press.–Wolfe, R.J., and R.J. Walker, 1987. Subsistence economies in Alaska: productivity, geography and development. Arctic Anthropology, 24(2):56–81.

- ↑ Callaway, D., J. Eamer, E. Edwardsen, C. Jack, S. Marcy, A. Olrun, M. Patkotak, D. Rexford and A. Whiting, 1999. Effects of climate change on subsistence communities in Alaska. In: G. Weller, P. Anderson (eds.). Assessing the Consequences of Climate Change for Alaska and the Bering Sea Region, pp. 59–73. Center for Global Change and Arctic System Research, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

- ↑ Caulfield, R., 2000. The political economy of renewable resource harvesting in the Arctic. In: M. Nuttall and T. V. Callaghan (eds.). The Arctic: Environment, People, Policy. Harwood Academic Press.

- ↑ Callaway, D., J. Eamer, E. Edwardsen, C. Jack, S. Marcy, A. Olrun, M. Patkotak, D. Rexford and A. Whiting, 1999. Effects of climate change on subsistence communities in Alaska. In: G. Weller, P. Anderson (eds.). Assessing the Consequences of Climate Change for Alaska and the Bering Sea Region, pp. 59–73. Center for Global Change and Arctic System Research, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

- ↑ Callaway, D., J. Eamer, E. Edwardsen, C. Jack, S. Marcy, A. Olrun, M. Patkotak, D. Rexford and A. Whiting, 1999. Effects of climate change on subsistence communities in Alaska. In: G. Weller, P. Anderson (eds.). Assessing the Consequences of Climate Change for Alaska and the Bering Sea Region, pp. 59–73. Center for Global Change and Arctic System Research, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

- ↑ Receveur, O., N. Kassi, H.M. Chan, P.R. Berti and H. V. Kuhnlein, 1998. Yukon First Nations’ Assessment Dietary Benefit/Risk. Report to communities. Centre for Indigenous Peoples’ Nutrition and Environment.