Introduction to Indigenous Peoples and Renewable Resource Use in the Arctic

Published: September 28, 2009, 1:34 pm Updated: August 2, 2012, 2:43 pm Author: International Arctic Science Committee (Introduction to Indigenous Peoples and Renewable Resource Use in the Arctic)

This is Section 12.1 of the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment

Lead Author: Mark Nuttall; Contributing Authors: Fikret Berkes, Bruce Forbes, Gary Kofinas,Tatiana Vlassova, George Wenzel

Indigenous peoples throughout the Arctic maintain a strong connection to the environment through hunting, herding, fishing, and gathering renewable resources. These practices provide the basis for food production and have endured over thousands of years, with cultural adaptations and the ability to utilize resources often associated with or affected by seasonal variation and changing ecological conditions.

Climatic variability and weather events often greatly affect the abundance and availability of animals and thus the abilities and opportunities to harvest and process animals for food, clothing, and other purposes. Many species are only available seasonally and in localized areas and indigenous cultures have developed the capacity and flexibility to harvest a diversity of animal and plant species. Indigenous cultures have, in many cases, also shown resilience in the face of severe social, cultural, and economic change, particularly in the last 100 years.

The longstanding dependence of present indigenous societies on hunting, herding, fishing, and gathering continues for several critically important reasons. One is the economic and dietary importance of being able to access customary, local foods. Many of these local foods – fish, and meat from marine mammals or caribou and birds, for instance, as well as berries and edible plants – are nutritionally superior to the foodstuffs which are presently imported (and which are often expensive to buy). Another reason is the cultural and social importance of hunting, herding, and gathering animals, fish, and plants, as well as processing, distributing, consuming, and celebrating them[1].

These activities remain important for maintaining social relationships and cultural identity in indigenous societies. They define a sense of family and community and reinforce and celebrate the relationships between indigenous peoples and the animals and environment upon which they depend[2]. Hunting, herding, fishing, and gathering activities are based on continuing social relationships between people, animals, and the environment[3]. As such, they link people inextricably to their histories, their present cultural settings, and provide a way forward for thinking about sustainable livelihoods in the future.

The significance of hunting, herding, fishing, and gathering has wide cultural ramifications. Seal hunting, for example, is not only an occupation and a way of life, but also a symbolic part of Inuit cultures[4]. The cultural role of activities relating to the use of living marine and terrestrial resources is not only of concern to those who depend economically on these activities, but also to those who live in towns and are involved in occupations with no direct attachment to hunting, fishing, and herding (e.g., [5]). Yet whatever the importance for social identity and cultural life, the primary need for, and use of animals is based purely on a need for survival.

Arctic communities have experienced, and are experiencing, stress from a number of different forces that threaten to restrict harvesting activities and sever these relationships. The arctic regions are tightly tied politically, economically, and socially to the national mainstream and are inextricably linked to the global economy[6]. Rapid social, economic, and demographic change, resource development, trade barriers, and animal-rights campaigns have all had impacts on hunting, herding, fishing, and gathering activities. The material in this chapter on the Russian North, for example, illustrates how poaching, oil development, and clear-cutting of forests undermine the subsistence base for indigenous peoples. Hunting, herding, fishing, and gathering are also being challenged by environmental changes such as climate variability. Despite this, indigenous peoples have reasserted cultural rights and identities, have called for the recognition of self-determination, and are achieving significant levels of regional government[7].

For many arctic residents, consuming food from animals is fundamentally important for personal and cultural well-being. Indigenous peoples have reported a loss of vitality, a decline in health, and a decrease in personal well-being when they are unable to eat traditional/country foods[8]. These problems do not just emerge when climate change denies people access to traditional/country foods, but are very much linked to problems associated with the undermining of local modes of production. The erosion of a person’s position as a provider of welfare to family and community also has serious ramifications. A recent study of the importance of whaling for Inuit societies illustrates the negative social, cultural, economic, and nutritional consequences of not being able to gain access to, and to eat, traditional/country foods[9] and points to the kinds of problems that indigenous peoples may experience if climate change denies them access to wild food resources.

The conservation of arctic wildlife and ecosystems depends in part on maintaining the strength of the relationship between indigenous peoples, animals, and the environment, and in part on securing the rights of indigenous peoples to continue customary harvesting activities. As this assessment shows, these activities and relationships appear to be threatened by severe climate change. The potential impacts of climate change on harvesting wildlife resources are of fundamental concern for the social and economic well-being, the health, and the cultural survival of indigenous peoples throughout the Arctic, who live within institutional, legal, economic, and political situations that are often quite different from non-indigenous residents. Furthermore, indigenous peoples rely on different forms of social organization for their livelihoods and well-being[10].

Many of the concerns about climate change arise from what indigenous peoples are already experiencing in some areas, where climate change is an immediate and pressing problem, rather than something that may happen, or may or may not have an impact in the future. For example, Furgal et al.[11] discussed local anxieties over environmental changes experienced by communities in northern Quebec and Labrador, and argued that the impacts on human health and the availability of important traditional/country foods from plants and animals can already be observed. Indigenous accounts of current environmental change say that such changes in climate and local ecosystems are not just evident in animals such as caribou shifting their migration routes and altering their behavior, but in the very taste of animals.

As the various chapters of this assessment show, scientific projections and scenarios suggest that there will be significant changes in the climate of the Arctic, in the character of the environment, and in its resources. For example, latitudinal shifts in the location of the taiga–tundra ecotone will have significant effects on ecosystem function and biodiversity at the regional scale. One dramatic anticipated change, taking place over several decades to hundreds of years, is the gradual forestation of tundra patches in the present forest–tundra mosaic and a northward shift of the treeline by hundreds of kilometers. These changes will affect vegetation structure and the composition of the flora and fauna and will have implications for indigenous livelihoods, particularly reindeer herding and hunting and gathering (see Chapter 7 (Introduction to Indigenous Peoples and Renewable Resource Use in the Arctic)).

The aims of this chapter are:

- to discuss the present economic, social, and cultural importance of harvesting renewable resources for indigenous peoples;

- to provide an assessment of how climate change has affected, and is affecting, harvesting activities in the past and in the present; and

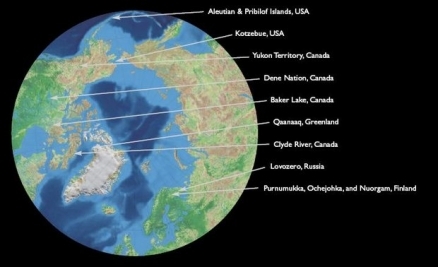

- through a selection of detailed case studies based on extensive research with indigenous communities in several arctic settings, to discuss some of the past, present, and potential impacts of climate change on specific activities and livelihoods.

The case studies were selected to provide a sense of the impacts that climate change is having in the present, or could have in the near future, on the livelihoods of indigenous peoples. It is not possible to provide circumpolar coverage of the situation for all indigenous peoples. Apart from space constraints, detailed descriptions are not available for all regions of the Arctic. The material presented in this chapter, especially through the case studies, illustrates the common challenges faced by indigenous peoples in a changing Arctic.

Another purpose of this chapter is to assess the adaptive strategies that have enabled communities to respond to and cope with climate change in the past and to establish the extent to which these options remain open to them. There are few data published on this topic, but based on those that are available the chapter shows that while indigenous peoples have often adapted well to past climate change, the scale and nature of current and projected climate change brings a very different sense of uncertainty for indigenous peoples, presenting different kinds of risks and threats to their livelihoods.

It should be noted that, compared to the scientific chapters in this assessment, data on the impacts of climate change on the livelihoods of indigenous peoples are limited, particularly in the case of the indigenous peoples of Russian North. The case studies in this chapter illustrate the complexity of problems faced by indigenous peoples today and underscore the reality that climate change is but one of several, often interrelating problems affecting their livelihoods.

This chapter is, therefore, as much a scoping exercise as it is an assessment of current knowledge. It emphasizes the urgency for extensive, [[regional]ly]-focused research on the impacts of climate change on hunting, herding, fishing, and gathering activities, research that will not just contribute to a greater understanding of climate impacts, but will place these impacts within the broader context of rapid social, economic, and environmental change.

Chapter 12. Hunting, herding, fishing, and gathering: indigenous peoples and renewable resource use in the Arctic

12.1 Introduction

12.2 Present uses of living marine and terrestrial resources

12.2.1 Indigenous peoples, animals, and climate in the Arctic

12.2.2 Mixed economies

12.2.3 Renewable resource use, resource development, and global processes

12.2.4 Renewable resource use and climate change

12.2.5 Responding to climate change

12.3 Understanding climate change impacts through case studies

12.3.1 Canadian Western Arctic: the Inuvialuit of Sachs Harbour

12.3.2 Canadian Inuit in Nunavut

12.3.3 The Yamal Nenets of northwest Siberia

12.3.4 Indigenous peoples of the Russian North

12.3.5 Indigenous caribou systems of North America

References

Citation

Committee, I. (2012). Introduction to Indigenous Peoples and Renewable Resource Use in the Arctic. Retrieved from http://editors.eol.org/eoearth/wiki/Introduction_to_Indigenous_Peoples_and_Renewable_Resource_Use_in_the_Arctic- ↑ Freeman, M.M.R. (ed.), 2000. Endangered Peoples of the Arctic. Greenwood Press, Westport, 304pp.

- ↑ Callaway, D., 1995. Resource use in rural Alaskan communities. In: D.L. Peterson and D.R. Johnson (eds.). Human Ecology and Climate Change: People and Resources in the Far North. Taylor and Francis.

- ↑ Brody, H., 1983. Maps and Dreams: Indians and the British Columbia Frontier. Penguin, Harmondsworth.–Callaway, D., 1995. Resource use in rural Alaskan communities. In: D.L. Peterson and D.R. Johnson (eds.). Human Ecology and Climate Change: People and Resources in the Far North. Taylor and Francis.–Freeman, M.M.R., L. Gogolovskaya, R. A. Caulfield, I. Egede, I. Krupnik and M.G. Stevenson, 1998. Inuit, Whaling and Sustainability. Altamira Press.–Nuttall, M., 1992. Arctic Homeland: Kinship, Community and Development in Northwest Greenland. University of Toronto Press.–Wenzel, G. W., 1991. Animal Rights, Human Rights: Ecology, Economy and Ideology in the Canadian Arctic. University of Toronto Press.

- ↑ Nuttall, M., 1992. Arctic Homeland: Kinship, Community and Development in Northwest Greenland. University of Toronto Press.–Wenzel, G. W., 1991. Animal Rights, Human Rights: Ecology, Economy and Ideology in the Canadian Arctic. University of Toronto Press.

- ↑ Caulfield, R. A., 1997. Greenlanders, Whales and Whaling: Sustainability and Self-determination in the Arctic Hanover. University Press of New England, 219pp.

- ↑ Caulfield, R., 2000. The political economy of renewable resource harvesting in the Arctic. In: M. Nuttall and T. V. Callaghan (eds.). The Arctic: Environment, People, Policy. Harwood Academic Press.–Nuttall, M., 1998. Protecting the Arctic: Indigenous Peoples and Cultural Survival. Routledge Harwood.–Osherenko, G. and O R. Young, 1989. The Age of the Arctic: Hot Conflicts and Cold Realities. Cambridge University Press.–Young, O., 1992. Arctic Politics: Conflicts and Cooperation in the Circumpolar North. Hanover, Dartmouth College.

- ↑ Nuttall, M., 1998. Protecting the Arctic: Indigenous Peoples and Cultural Survival. Routledge Harwood.

- ↑ Wein, E.E. and M.M.R. Freeman, 1992. Inuvialuit food use and food preferences in Aklavik, Northwest Territories, Canada. Arctic Medical Science, 51:159–172.

- ↑ Freeman, M.M.R., L. Gogolovskaya, R. A. Caulfield, I. Egede, I. Krupnik and M.G. Stevenson, 1998. Inuit, Whaling and Sustainability. Altamira Press.

- ↑ Freeman, M.M.R. (ed.), 2000. Endangered Peoples of the Arctic. Greenwood Press, Westport, 304pp.

- ↑ Furgal, C., D. Maritn and P. Gosselin, 2002. Climate change and health in Nunavik and Labrador: lessons from Inuit knowledge. In: I. Krupnik and D. Jolly (eds.). The Earth is Faster Now: Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change, pp 266–300. ARCUS.