Responses to genetically modified crop use in Africa

Contents

- 1 Introduction Box 1: Doing the right thing is not simple (Source: CBD and UNEP 2005) There are a wide range of responses, at multiple levels, to the growing challenges posed by the development of genetic modification (GM) technologies and products. These include global and regional intergovernmental responses, science-based responses and civil society initiatives. As a whole, the overall approach of African governments has been to encourage a range of biotechnology research (both transgenic and non-transgenic) while recognizing biosafety concerns and establishing systems to limit its impact. Box 2: The African Biotechnology Stakeholders Forum (Souce: ABSF undated) Biosafety approaches have been shaped by the worldwide acknowledgement of the growing threats which ecosystems and biodiversity (Responses to genetically modified crop use in Africa) face from human activity, and the long-term implications this has for development and human well-being. The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) secretariat along with UNEP for example notes: “The stakes are high: although some 40% of the world economy is derived directly from biological diversity, humanity is pushing ecosystems, species and gene pools to extinction faster than at any time since the dinosaurs died out 65 million years ago. At present, natural habitats and ecosystems are being destroyed at the rate of over 100 million hectares (ha) every year. More than 31,000 plant and animal species are threatened with extinction; according to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the UN, at least one breed of livestock dies out every week. Bandaids are not enough: only a fundamental and far-reaching solution can ensure a biologically rich world for future generations” (CBD and UNEP 2003).

- 2 Science-based risk analysis

- 3 Substantial equivalence and familiarity

- 4 Integrative approaches

- 5 Legal and policy issues

- 6 Cartagena Protocol

- 7 Regional responses

- 8 Sub-regional approaches

- 9 National policy and law

- 10 Further reading

Introduction Box 1: Doing the right thing is not simple (Source: CBD and UNEP 2005) There are a wide range of responses, at multiple levels, to the growing challenges posed by the development of genetic modification (GM) technologies and products. These include global and regional intergovernmental responses, science-based responses and civil society initiatives. As a whole, the overall approach of African governments has been to encourage a range of biotechnology research (both transgenic and non-transgenic) while recognizing biosafety concerns and establishing systems to limit its impact. Box 2: The African Biotechnology Stakeholders Forum (Souce: ABSF undated) Biosafety approaches have been shaped by the worldwide acknowledgement of the growing threats which ecosystems and biodiversity (Responses to genetically modified crop use in Africa) face from human activity, and the long-term implications this has for development and human well-being. The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) secretariat along with UNEP for example notes: “The stakes are high: although some 40% of the world economy is derived directly from biological diversity, humanity is pushing ecosystems, species and gene pools to extinction faster than at any time since the dinosaurs died out 65 million years ago. At present, natural habitats and ecosystems are being destroyed at the rate of over 100 million hectares (ha) every year. More than 31,000 plant and animal species are threatened with extinction; according to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the UN, at least one breed of livestock dies out every week. Bandaids are not enough: only a fundamental and far-reaching solution can ensure a biologically rich world for future generations” (CBD and UNEP 2003).

The range of actors involved in policy development has increased dramatically. Governments, scientists, the private sector and civil society have all become active players. The extent to which the concerns and interests of these respective groups are acknowledged varies between countries and across issues. However, as Box 1 shows, given the complexity of the issues and the risks associated with them, a growing number of policymakers, at the national, regional and global levels, are acknowledging the importance of inclusive policy processes. Box 2 looks at one initiative that brings together stakeholders at the regional level. Table 1 shows some of the national, subregional and regional organizations active in biotechnology issues.

Science-based risk analysis

Risk analysis is concerned with how to evaluate, contain or avoid negative impacts resulting from the uncertain behaviour of GM products and processes. To be effective, such assessments need to address all costs-and-benefits, and not be restricted to financial expenditures and profits. It needs to address direct and indirect costs-and-benefits, as well as opportunity costs, such as the impact on environmental goods-and-services as well as on agricultural and social systems. Field trials and how crops behave in conditions similar to those following actual release are a critical step in the assessment process, allowing product developers to address problems arising. They play an important role in identifying risks and creating an opportunity for mitigation and adaptation prior to full release.

However, the standardized approach to risk assessment does not allow for such levels of complexity. Most national risk analysis frameworks focus on risk-benefit assessments that are derived from economic cost-benefit type analysis. In general, they adopt narrow technical approaches, which focus on the characteristics of the host organism and the resulting GMO, the expression and properties of the gene product and the biophysical features of the recipient environment. These approaches and their general principles have been developed over several decades in response to technological development in the chemical and pharmaceutical industries. These standardized approaches are particularly attractive to companies and governments as they are simplified and avoid the costs of case-by-case analysis.

Two factors underlie the analysis of risk:

- The magnitude of each potential harm or benefit that might occur; and

- The likelihood of its occurrence.

Magnitude is particularly important from a human and environmental perspective; certain kinds of changes, such as biodiversity loss, may be irreversible. Magnitude is difficult to ascertain where there is insufficient experience with a product or activity. Likelihood is based on comparison with similar situations in the past.

Substantial equivalence and familiarity

In the area of GM crops, many national assessment systems are based on the concepts of “substantial equivalence” and “familiarity” to determine the likelihood of potential harm and to decide on further product testing and development as well as commercial release. In general, it neglects the socioeconomic aspects.

The concept of familiarity has been used in the chemical industry to determine safety levels on the assumption that closely related chemicals will behave in the same way. This approach is now used in GM risk assessment. Such models have a high level of appeal because they do not require regulators to deal with complex and case-specific factors. This framework neglects the issue of magnitude and rare but significant impacts. It may not be as well suited to LMO as these can behave in unpredictable ways.

Substantive equivalence between organisms is used as an indication of how they will behave. The concept was originally developed as a way for determining food safety. If a new GM product is substantially equivalent in chemical composition to its natural antecedent then it is assumed to be safe. This approach neglects the uncertainties around the actual modification of DNA.

Integrative approaches

(Source: M. Pimbert)

Risk is different from cost because, on the one hand, a certain level of risk is necessary for social, political and economic advancement and, on the other, risk is by its nature uncertain. The challenge in the area of GM is that risks posed by this technology are fundamentally different from those posed by earlier agricultural technologies. The range of uncertainties is greater than ever before and includes fundamental scientific uncertainties and ignorance about the potential environmental and health risks, as well as wider uncertainties about the impact on agricultural systems and rural livelihoods. The importance of recognizing uncertainties and ignorance is evident from the Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE) crisis, or mad cow disease, which resulted in major economic and health costs in the UK and Europe. Classical assessment approaches which treat scientific aspects separately from ethical, moral, social and economic considerations may be inappropriate and have been widely criticized over many years. In this context of uncertainty, other approaches, including the precautionary approach, can be a valuable part of risk assessment. Taking a precautionary approach requires acknowledging the potential for unforeseen consequences, complex effects and ignorance. The precautionary approach offers the opportunity to address normative values of justice, fairness and responsibility which classical risk assessment does not do.

A further challenge for risk assessment processes is that the range of actors in the development of new policy making and the negotiation process of regulatory and policy frameworks is wider than ever before: it includes global institutions, multinational companies, NGOs, governments and intergovernmental bodies, scientists and farmers acting at and across national, regional and global levels. This highlights the need for deliberative participatory processes over simple consultation. Participation is successful when it promotes responsiveness to local and national needs, legitimacy and “ownership” of policy and law. Thus, the processes for participation need to be appropriate and relevant to the country concerned. Many African countries have recognized this: participatory approaches have been used in policy development in relation to national law and policy development. Current risk assessment processes are closely allied to globalization in which individual (R&D, economic and propriety) rights trump social and cultural rights and concerns; these issues are assumed to be adequately addressed through the market and consumer choice.

A range of approaches that deal with such complex decision making have been developed which recognize the plurality of views as well as a level of uncertainty and ignorance. These include quantitative approaches designed to examine the multicriteria important in decision making, scenario approaches which systematically analyse future options, and deliberative participatory approaches; these approaches introduce rigour not by limiting the issues under consideration but by being transparent and addressing the full complexity of the issues.

Legal and policy issues

The introduction of GMOs has brought new challenges for authorities and policymakers who have to consider impacts on human health, poverty and hunger, livelihoods and food security, free trade and international markets, and the environment, particularly biodiversity. Laws and institutions need to ensure that an acceptable trade-off between competing and often conflicting interests is maintained. As GMO technology is relatively new, governance systems are also in their infancy and have not been able to take all these challenges on board.

Africa is responding to these challenges at multiple levels. It has supported initiatives at the global level such as the CBD and its Cartagena Protocol. It has developed cutting-edge solutions at the regional level such as the African Union’s (AU) Model Law on Safety in Biotechnology (African Biosafety Model Law) and has begun to develop national frameworks for GMO development and biosafety. The AU has also adopted a Model Law for the Protection of the Rights of Local Communities, Farmers, Breeders and Regulation of Access to Biological Resources.

The AU’s Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) promotes an integrated multilevel response to the challenges of agriculture. This framework should serve as the basis for developing agricultural strategies. As the Millennium Task Force on Science and Technology cautions, technology cannot of itself determine social change but it can be a useful tool when aligned with development goals and when supporting governance structures are created.

Cartagena Protocol

At a global level, the key response to concerns about biosafety is the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety adopted in 2000 under the CBD of 1992. The Protocol is primarily concerned with transboundary movement of living modified organisms (LMOs); it provides a framework for countries to assess risks associated with LMO prior to authorizing importation. It seeks to ensure:

“An adequate level of protection in the field of the safe transfer, handling and use of living modified organisms resulting from modern biotechnology that may have adverse effects on the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity, taking also into account risks to human health, and specifically focusing on transboundary movements” (Secretariat of the CBD 2000).

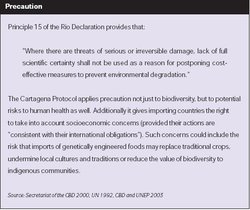

Two key concepts, biosafety and precaution, form the basis for the framework developed in the Protocol. Biosafety is based on the concept of precaution and implies minimizing the risk to human, animal and environment health (see Box 3). It includes a range of measures, policies and procedures to minimize potential risks. The precautionary approach has been specifically incorporated in the Protocol.

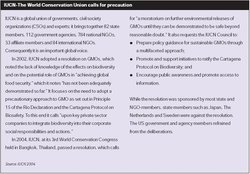

Although there remains much controversy about what exactly constitutes a precautionary approach, there is evidence of wide support for it as reflected in Box 4. The Cartagena Protocol applies the precautionary approach to biodiversity and to human risks. It gives importing countries the right to take socioeconomic considerations into account, as long as these are consistent with their international obligations. The Protocol allows governments on the basis of precaution to prohibit the import of a GMO, even where there is insufficient scientific evidence about potential adverse effects.

The Protocol entered into force in July 2003. Although the Protocol has been signed by 37 African countries, many of these have not yet ratified it or developed laws to incorporate it into their legal framework: Algeria, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Libya, Madagascar, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Seychelles, South Africa, Sudan, Swaziland, Togo, Tunisia, Uganda, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Table 2 shows the status of the Cartagena Protocol in African countries.

African countries are faced with the challenge of dealing with transboundary movement of GMOs and illegal use or research activities. Some African country borders are porous, difficult to police and at times subject to bribery. GM maize and rice are already being planted illegally in various regions of Tanzania. Adoption and ratification of the Protocol could be a useful option. In the absence of effective monitoring and enforcement, bans on the import of GM seeds are of no effect. The shipment of grain requires leak-proof containers to avoid unintended GMO product contamination. Therefore, responsible deployment of GM crops needs to encompass the whole technology development process, from the pre-release risk assessment, to biosafety considerations, to post-release monitoring. Monitoring GM crops will provide information for policies and regulations; it will give producers and policymakers better information to help them develop safer adoption processes.

Regional responses

The African Biosafety Model Law was adopted by the AU at its 74th Ordinary Session in Lusaka, Zambia, in July 2001, and urged member states to use the African Biosafety Model Law to draft their own national legal instruments.

This model law emanated from a highly participatory process which included researchers, governments, and civil society groups. It reflects a broad consensus on issues of biotechnology development. The regulatory framework utilizes the discretion given by the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety for countries to adopt more stringent protective measures than the agreed minimum set out in the Protocol. The African Biosafety Model Law recognizes the importance of Africa as a centre of origin and a centre of diversity with regard to food and other crops. It makes provision for considering socioeconomic factors in assessing risks and opportunities. Key legal principles and approaches incorporated include:

- Precautionary;

- The sovereign right of every country to require a rigorous risk assessment of any GMO for any use before any decision regarding the GMO is made; and

- A liability and redress regime.

The African Biosafety Model Law provides a holistic and comprehensive set of biosafety rules including issues that are not dealt with by the Biosafety Protocol. These include mandatory labelling and identification or traceability requirements for GMOs and GM food, and liability and redress for harm caused by GMOs to human health and the environment, and for resultant economic loss (Mayet 2003).

Sub-regional approaches

Box 5: SADC recommendations on genetically modified organisms

Box 5: SADC recommendations on genetically modified organisms(Source: SADC 2004)

Six regional economic communities in Africa, namely the Economic Commission of West African States (ECOWAS), the East African Community (EAC), the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the Arab Mahgreb Union (AMU) have taken the lead in developing policy guidance on GMO research, production and marketing in their respective regions.

In Kampala, in November 2002, agricultural ministers of the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), agreed to create a regional policy on GMOs. Similarly, the SADC established an advisory committee on GMOs to develop guidelines and to assist member states in guarding against potential risks in food safety, contamination of genetic resources, ethical issues, traderelated issues and consumer concerns. These are set out in Box 5. The EAC has recommended reviewing and developing a common policy on GMOs. The IGAD members formed a Verification and Monitoring Team (VMT) to ensure that food assistance be certified as free of GMOs. Fifteen members of ECOWAS attended a meeting to better understand and discuss the benefits and threats of GMOs.

National policy and law

The need for adequate national policies and laws to regulate biotechnology research and establish effective assessment processes which safeguard human and environmental health is widely acknowledged. There is a need to develop harmonized approaches to biotechnology and the African Biosafety Model Law provides a good basis for this, as does the Model Law for the Protection of the Rights of Local Communities, Farmers, Breeders and Regulation of Access to Biological Resources. Other region-wide organizations such as New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD), and its Science and Technology Secretariat could have an important role.

At least nine countries have biosafety legislation or guidelines including Benin, Cameroon, Malawi, Mauritius, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho and Swaziland all have draft legislation that addressees the issue of biosafety, the commercialization of GM crops and the importation of GM foods.

Developed country aid agencies and international organizations have had a keen interest in supporting the development of an enabling legal environment for transgenic research and biosafety. Some of these initiatives appear in Annex 3 Table 2. The United States Agency for International Development is the most active in this area. The US has been a keen supporter of GM crop development, offering it as food aid, and the US is also the largest producer of GM crops. Several African countries have or are in the process of developing biosafety policies and law through a United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) – Global Environmental Facility (GEF) initiative. This capacitybuilding project supported 100 developing countries to prepare national biosafety frameworks. Thirty-six African countries have or are participating in this project. An AU biosafety capacity-building project designed to spearhead the harmonization of biosafety legislation between member states based on the African Biosafety Model Law has been developed.

Further reading

- Balile, D., 2005. Minister says Tanzania is growing GM tobacco. Science and Development Network News, 22 April.

- CBD, 2006. Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety (Montreal, 29 January 2000) – Status of Ratification and Entry into Force.

- CBD and UNEP, 2003. Biosafety and the Environment: An introduction to the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety. Convention on Biological Diversity and the United Nations Environment Programme.

- FAO, 2005. Annex 3: Special Note From The Experts Who Participated In The Consultation. In Genetically modified organisms in crop production and their effects on the environment: methodologies for monitoring and the way ahead. Report of the Expert Consultation, 18-20 January. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

- Glover, D., 2003b. Public participation in National Biotechnology Policy and Biosafety Regulation. IDS Working Paper 198. Institute of Development Studies, Brighton.

- GMWatch, 2005. Rumpus over GMO’s in Africa.

- Mohamed-Katerere, J.C., 2003. Risk and rights: challenging biotechnology policy in Zimbabwe. IDS Working Paper 204. Institute of Development Studies, Brighton.

- Scoones, I., 2002. Science, policy and regulation: challenges for agricultural biotechnology in developing countries. IDS Working Paper 147. Institute of Development Studies, Brighton.

- UN Millennium Project, 2005b. Innovation: Applying Knowledge in Development. Task Force on Science,Technology, and Innovation. Earthscan, London.

- UNEP, 2006. Africa Environment Outlook 2.

- UNEP, 2006. Africa Environment Outlook 2, ANNEXES.

- Young, T., 2004. Genetically Modified Organisms and Biosafety: A background paper for decision-makers and others to assist in consideration of GMO issues. IUCN – The World Conservation Union, Gland.

|

|

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |