Regional scenarios for Africa's future: freshwater

The interfacing and changes in these key driving forces, as used in the narratives in this chapter, are assumed to take the patterns reflected in Figure 1. The narratives presented in the subsequent sections are based on these patterns of change in the main driving forces.

In order to provide a holistic storyline, the regional and sub-regional narratives have been integrated for some issues while stand-alone sections have been reserved for issues more directly relevant to specific sub-regions. The four regional narratives focus on transboundary aspects and ecosystems at sub-regional and regional levels, and discuss the implications of policy choices for meeting the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) targets by 2025. The analysis is undertaken in the context of the Opportunity Framework (see Introduction). The policy lessons from the scenarios are closely related to the future state of the environment as presented in Section 2: Environment State-and-Trends: 20-Year Retrospective.

Freshwater

The key issues, for which scenarios have been presented under the freshwater theme, revolve around transboundary water resources management. As discussed in Chapter 4: Freshwater (Regional scenarios for Africa's future: freshwater), the potential methods for increasing the opportunities associated with Africa’s freshwater resources include the adoption of river basin or catchment management, improved regional cooperation, enhanced and more equitable distribution of water, better sanitation and the recognition of water as an asset for environmental management. Opportunities can only be harnessed if the issues and threats facing resource sustainability are understood and addressed. Issues regarding water quality and quantity, availability, variability and accessibility, low levels of investment in water infrastructure and technology, exploration and assessment of freshwater (including groundwater) potential, water-borne diseases (such as schistosomiasis (bilharzia) and onchocerciasis (river blindness)), invasive alien species (IAS) and competition (conflict) over resources are critical to sustainable management of Africa’s water resources and achieving the MDG 7 targets of halving the proportion of people without improved drinking water in urban and rural areas, and halving the proportion of people without sanitation in urban and rural areas.

The main driving force and pressure for changes in the state of freshwater is population growth, although climate change is also a driver. This is evident in [[Chapter 4: Freshwater (Regional scenarios for Africa's future: freshwater)]2] and it was also highlighted in the Africa Environment Outlook 1 (AEO-1) scenarios. The availability of water, both absolute and per capita, is a consequence of the growing number of people in Africa. There is growing demand for water for agricultural and industrial development, which can potentially lead to water scarcity. Population increases can also precipitate competition and conflict over available freshwater. Such conflicts may be between different economic sectors and, in some cases, between countries, or between communities which share common water bodies. Other drivers that affect the state of freshwater resources, and thus development opportunities, include climate, technological developments and socioeconomic and health factors. These driving forces are assessed in the following scenario narratives. The scenario narratives reveal the implications of different policy choices for realizing key objectives.

Market Forces scenario

Increasingly, Africa will be the home to environmentally harmful industries, including the chemical industry (see Chapter 11: Chemicals). This trend is related to increased measures for environmental protection in developed countries and an increasingly active civil society. In these circumstances, investors and industries target the still less restrictive legal systems, which are found predominately in the developing world. Northern Africa, given its strategic location close to Europe, and South Africa, with its more developed markets, become focuses of investment. Many new factories are established to manufacture the goods in Africa and then export them to Europe. The move appeals to and is welcomed by the local African governments, as it seems to be a magic solution to their struggling economies.

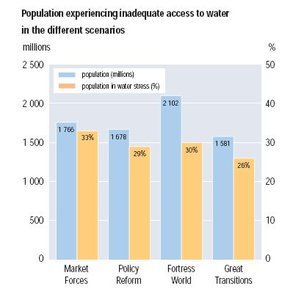

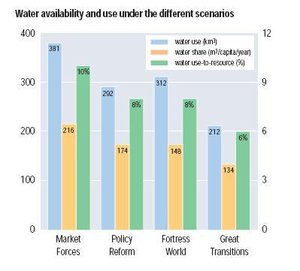

Rapid population growth does not seem to be a problem because the flourishing industry absorbs some of the unemployed population. However, the capacity of the African countries to develop their water resources and use them more efficiently still remains very low. Total annual water use amounts to 381 km3 that is about 10 percent of available resources. With the population reaching 1,766 million by 2050, per capita water share is very low at 216 m3/year. However, large variations are witnessed among the sub-regions.

There is an increase in industrial water use (16 per cent) in order to produce and ensure continued FDI.

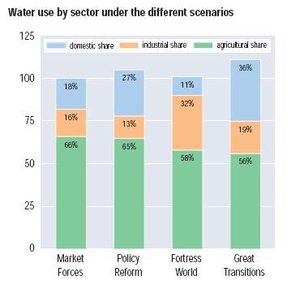

Competition over limited water resources rises between some sectors. Agriculture, the main water consumer, enjoys a large share of the resource (66 percent of the total) as it feeds the industries with some raw materials and exports agricultural products to foreign markets. There is also an increase in industrial water use (16 percent) in order to produce and ensure continued FDI. Domestic water use is 18 percent of the total. Surface water is mainly used for irrigated agriculture, whereas industry and some urban areas rely more on groundwater.

Overharvesting of groundwater by the industrial sector poses a serious risk to the sustainability of the resource, but governments feel unable to impose strict regulations on that powerful sector. In response, the governments try to reduce water use in public irrigation schemes and reduce expenditure in water utilities by privatizing them or turning them over to the beneficiaries. This move is intended to improve resource-use efficiency and bring the costs of operation and maintenance down. However, some of the utilities need large investments in order to rehabilitate them and make them profitable. The private sector makes those investments but also raises service fees. The prices of potable water in some urban centres and large cities become very high and unaffordable for many people. Therefore, although more people are connected to the water networks, the number of people who can afford to pay for it decreases. Alternative cheap, but unsafe, water sources emerge and the use of these increases. Many people are affected by water-borne diseases, which add to the strain on the national economies.

In this scenario, the economic and technological gap between urban and rural areas increases and there is a concentration of economic activities, particularly industry, around the urban areas. Typically, many people are attracted to move from rural to urban areas in search of better lives and incomes. However, because they are mostly unskilled labourers, they can only secure low income jobs and hence find themselves unable to cope with the high living costs in the urban areas. Slums proliferate on the outskirts of the large urban areas. Services are very minimal and of low quality. Untreated sewage water poses a serious risk to those communities as well as to surface and shallow groundwater resources in the downstream areas.

Policy Reform scenario

In this scenario, there is a clear shift in the development policies of countries, with water, along with other environmental resources, taking a higher priority than before. The new policies are centralized around some main goals: better availability of and access to water resources, equitable distribution of the resources among all beneficiaries, and the sustainable use of water resources in terms of both quantity and quality.

Overall, Africa is not short of water resources, but it is the spatial distribution of the resource that is rather uneven. Some countries, notably in Northern Africa, the Horn of Africa, and Southern Africa are experiencing water stress, while others, in Central Africa for example, have ample resources that are as yet untapped. This opens up opportunities for cooperation between different groups of riparian countries for the optimum use of the water resources for the benefit of all nations.

Nevertheless, until the above efforts materialize and start to achieve their goals, water availability is restricted by technical and financial obstacles. Despite a moderate increase in the population (1,678 million), total annual water use is only 292 km3 or just 8 percent of available resources. The per capita water share is therefore very low at 174 m3/year.

In meeting policy goals, attention is given to rural populations who have long been neglected. New water supply projects, financed by international donors and lending agencies, provide good quality and safe potable water to the rural populations. The objectives are two-fold:

- Safe potable water should improve population health leading to significant savings in expenditure on health care.

- Improving the quality of life in the rural areas should help reduce the tide of urbanization.

However, some difficulties are experienced. First, the cost of tap water is relatively high and unaffordable for most people in the rural areas. Second, the availability of better water supply without improved sanitation results in substantial health hazards as well as environmental risks, as people simply dump their increased volumes of untreated sewage water in watercourses. The problems are well known to the governments, but they are unable to take timely action due to limited financial resources. Technocrats and environmentalists advocate that rural areas should be provided with sanitation first, whereas politicians believe that water supply should take the first priority as water is an essential requirement for life.

Similarly, urban areas also benefit from the new policies and more people are connected to water supply networks. More people have access to safe potable water. Water tariffs also increase, and they are higher than those in the rural areas. Water use for domestic purposes is at a record high of 27 percent of total water use. As technical solutions are not available to protect the quality of water resources, governments adopt laws and regulations to protect water quality. It takes time, though, until the public begin to adopt sustainable water-use practices. Law enforcement along with public awareness campaigns, financial incentives and other economic instruments are among the tools used to promote more efficient and sustainable use.

The use of groundwater is rationalized through new policies, which target integrated water resource management (IWRM). Water resources have become so vulnerable that any further misuse can lead to a state that will be extremely difficult to remedy. In response, priority for groundwater use is given to small communities and industries. Small communities mainly use shallow groundwater for domestic purposes, which can be easily contaminated if not properly protected. Industries rely more on deep groundwater, which requires good management to maximize the lifespan of the wells. Many countries acknowledge the fact that some of their deep groundwater aquifers are shared with their neighbours. For the first time, those countries sit together and draw plans for the sustainable utilization of this common resource, an act that has for long been limited to riparian countries only.

Fortress World scenario

In many developing countries, the differences between rich and poor are phenomenal and growing. Wealth and poverty are closely related to dispossession and deprivation, and to the extent of capabilities people have to make livelihood choices they value (Sen 1999). In many countries, the middle class is gradually diminishing and this trend is expected to continue under this scenario. The gap between rich and poor people gets wider, increasing the potential for conflict over natural resources. Although much smaller in numbers, the rich have the upper hand and therefore manage to control almost everything; this is done at the expense of the environment and sustainable water resources management.

Water availability varies considerably across Africa. In all societies, irrespective of social values or wealth, water is a vital resource. In the Fortress World scenario, the elite are very keen to maintain full control of this resource. Their control is not limited to the use and distribution of internal waters but goes beyond national boundaries, as a result of their influence on water management institutions in neighbouring countries. Transboundary technical and economic cooperation is minimal, with each country focusing on its own needs. In pursuit of huge profits, the elite focus on industry and trade with the West. They take advantage of the low cost of raw materials available in Africa and of abundant cheap labour. Water use by the industrial sector is high at 32 percent of the total use, and is at the expense of the agricultural sector and domestic water use among poor people. Many industries produce environmentally-hazardous waste that is disposed of without any treatment, further threatening freshwater systems.

(Source: UNEP 2006)

Potable water supply to the elite urban areas is secured. Domestic water use accounts for 11 percent of the total annual water use of 312 km3. Per capita water share is very low at 148 m3 per year due to the large increase in population (2,102 million). However, water availability and distribution is skewed with the elite taking much higher shares than poor people. About 30 percent of the population, mainly poor people, have inadequate access to water resources and are not able to meet their basic needs. This deteriorating situation is just one factor undercutting the opportunities available to poor people. Faced with no access to resources – natural resources, education, health care, among others – poverty increases.

Agriculture is embarked upon primarily to meet subsistence needs, however the lack of water availability makes this a challenge. Water that is available is of poor quality, and the impact of this on the quality of agricultural products and soils, from salinization and other pollutants, is evident.

Domestic water availability for poor people, whether in rural areas or on the fringes of urban areas, is very limited. The shortage of potable water is so acute that people have to use low-quality water. Disputes on access to potable water arise almost daily with the stronger getting higher shares than the weak. Female-headed households are at a particular disadvantage. Used domestic and industrial wastewater is disposed of in open watercourses causing serious damage to ecosystems and biodiversity, as well as to the health of poor people living in downstream areas. There is an outbreak of water-borne diseases such as malaria, bilharzia and diarrhea. Most affected are poor people, particularly children under five, due to inadequate access to good health care, and infant mortality is high.

Groundwater resources are not spared. The elite overharvest deep groundwater for their new modern urban compounds and leisure centres. Well-digging is neither regulated nor documented. No databases for the numbers and locations of wells exist. The exact amount of annual groundwater use is not known. The typical symptoms of groundwater degradation, such as declining water tables and increased well salinity, are evident. Many poor rural areas have to use shallow groundwater for domestic purposes. This water is not completely safe, but it is of better quality than that from many surface sources. Shallow groundwater is polluted by both seepage from polluted surface water sources and the poor management of the wells by the users themselves. Many wells are in very bad condition and need urgent rehabilitation, but the users, who are poor, lack the required technical and financial resources.

Great Transitions scenario

In this scenario, African countries fundamentally transform their water management policies and practices. The reforms aim at ensuring the sustainable use of all natural resources while at the same time improving living standards and well-being.

Agricultural practices which adversely affect water sustainability are no longer tolerated as there is proper enforcement of the law. For example, the use of cheap and illegal chemicals is successfully prevented through better monitoring and law enforcement, and public education. Modern irrigation systems that are highly efficient in water use become common practice in most of the better-off countries. As an incentive to farmers, the governments set special energy tariffs for agricultural uses. The tariffs, however, are not so low so as to encourage unsustainable energy and water use. Agricultural water use is successfully controlled at only 56 per cent of the total water use, a significant reduction from current trends where as much as 85 to 90 percent of water use is for agricultural purposes.

The reform in the agricultural sector encourages many foreign investors to establish farms. The availability of good land and water resources, low-cost labour and enabling national policies and laws encourages this development. The industrial sector also flourishes in light of the reform in policies and availability of raw materials. Industrial water use therefore increases to 19 percent of the total use. Improved regulations require that industrial waste must be properly treated before it is disposed of. Samples of industrial wastewater are collected randomly and analyzed to ensure that they comply with the regulations and are safe for disposal, and systems for self-monitoring are also established. This level of monitoring and enforcement is made possible through increased investment in human resource capacity.

Special attention is paid to the rural population. International aid and donors focus on water supply and sanitation projects in these areas. The target is to develop sustainable means of water supply and sanitation, using appropriate technology, which meets the needs of rural people. Partnerships are developed with potential users, who provide in-kind contributions. As an integral part of this investment, public education activities are embarked upon that focus on maintaining the new systems and infrastructure, to ensure the sustainability of supply. These initiatives are complemented by national level reforms, including in supply and treatment of water resources. Privatization of the water supply utilities, especially those supplying water to the urban areas, is seen as a necessity if the efficiencies of those utilities are to be increased. However, privatization usually comes with a higher cost of services and tariffs to the users. The tangible improvements in the quality of the services justify the higher costs to the users. In addition, higher living standards as a result of economic reforms and growth mean that most of the population can afford the high service fees and tariffs.

Nevertheless, as more people are provided with safe potable water, and due to the higher living standards, domestic water use sharply rises to 36 percent of the total use. This is not necessarily a good indicator of better water availability to more people, but is related to overuse of water among the more wealthy in urban areas. In fact, although rapid population growth is successfully controlled through better education of young people, 26 percent of the 1,581 million people in Africa still have inadequate access to water. Public campaigns and awareness programmes target wasteful use of water. Every saved drop of water simply means better water availability to others in the same country and across the boundaries in downstream countries.

Many African governments adopt new policies or reemphasize existing policies for stakeholder participation in management and decision making in water-resources related issues. The rationale is that if the stakeholders are involved in water resources management, they will develop a sense of ownership and become key players in sustaining those resources. Formal and informal water user associations are established to promote better communication and exchange of information between government and users. One of the lessons learned is that illiteracy is not a justification for excluding users from decision making. These associations are successful and are replicated at the national level.

Policy lessons from the scenarios

The different scenarios illustrate the potential for meeting agreed goals and targets, such as those of the Africa Water Vision 2025 and the MDGs under different policy options. In particular, opportunities for realizing the MDG targets related to access to water and sanitation are revealed. In addition, the different scenarios hold distinct potentials for meeting economic and development opportunities. Similarly, as illustrated in Box 1, different governance choices will also affect opportunities.

Taken as a whole, the scenarios demonstrate the complexity of the challenge of optimizing water use so as to meet human well-being and development targets, while ensuring the sustainability of the resource. One policy lesson that comes from various scenarios is the opportunities at all levels offered by adopting IWRM. Addressing and reconciling different needs in an equitable and productive manner will require policy and law reform, as well as investment in technology. Building human resource capacity also emerges, in several scenarios, as an invaluable means for enhancing opportunities. Further, establishing collaborative management regimes at the national as well as at the inter-state level is paramount to achieving sustainable water management.

Further reading

- ECA, AU and AfDB, 2000. The African Water Vision for 2025: Equitable and Sustainable Use of Water for Socioeconomic Development. Economic Commission for Africa, African Union and African Development Bank. Addis Ababa.

- OECD, 2001. Environmental Outlook for the Chemicals Industry. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

- UNEP, 2002c. Vital Water Graphics: An Overview of the State of the World’s Fresh and Marine Waters. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi.

- UNEP, 2006. Africa Environment Outlook 2.

|

|

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |