Pipeline Safety in the United States

Contents

Current status

On September 7, 2011 the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure introduced the The Pipeline Safety, Regulatory Certainty, and Job Creation Act of 2011 (H.R. 2845), a bill to enhance pipeline safety and abet job creation. The bill was authored under leadership of John Mica (R-Fl) by the Republican controlled Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure and passed by the Republican controlled House of Representatives on December 12, 2011; the law took effect on January 3, 2012 after Senate approval.

Overview

Nearly half a million miles of pipeline transporting natural gas, oil, and other hazardous liquids crisscross the United States. While an efficient and fundamentally safe means of transport, many pipelines carry materials with the potential to cause public injury and environmental damage. The nation’s pipeline networks are also widespread and vulnerable to accidents and terrorist attack. The 2006 partial shutdown of the Prudhoe Bay, Alaska oil field, and the 2010 pipeline accidents in Marshall, Michigan, San Bruno, California, Allentown, Pennsyvannia, and Laurel, Montana have demonstrated this vulnerability and have heightened congressional concern about pipeline risks. Both government and industry have taken numerous steps to improve pipeline safety and security over the last 10 years. While many stakeholders agree that federal pipeline safety programs have been on the right track, recent pipeline incidents suggest there continues to be room for improvement. Likewise the threat of terrorist attack on U.S. pipelines remains a concern.

| Note: This article was derived from the Congressional Research Service ReportR41536 Keeping America’s Pipelines Safe and Secure: Key Issues for Congress by Paul W. Parfomak |

The U.S. Congress is considering new legislation to improve the safety and security of the U.S. pipeline network. Proposed changes in law would:

- require pipeline operators to provide immediate telephonic notice of a pipeline release to federal emergency response officials;

- increase civil penalties for pipeline safety violations;

- increase the number of federal pipeline safety inspectors;

- require automatic shutoff valves for natural gas pipelines;

- mandate internal inspections of transmission pipelines;

- require public access to pipeline emergency response plans;

- change natural gas pipeline integrity assessment intervals; and,

- mandate a new federal pipeline security study.

As Congress debates reauthorization of the federal pipeline safety program and oversees the federal role in pipeline security, key questions may be raised concerning pipeline agency staff resources, automatic pipeline shutoff valves, penalties for pipeline safety violations, and the possible need for pipeline security regulations. In addition to these specific issues, Congress may wish to assess how the various elements of U.S. pipeline safety and security activity fit together in the nation’s overall strategy to protect transportation infrastructure. Pipeline safety and security necessarily involve many groups: federal agencies, oil and gas pipeline associations, large and small pipeline operators, and local communities. Reviewing how these groups work together to achieve common goals could be an oversight challenge for Congress.

Introduction

Nearly half a million miles of high-volume pipeline transport natural gas, oil, and other hazardous liquids across the United States.1 These transmission pipelines are integral to U.S. energy supply and have vital links to other critical infrastructure, such as power plants, airports, and military bases. While an efficient and fundamentally safe means of transport, many pipelines carry volatile, flammable, or toxic materials with the potential to cause public injury and environmental damage. The nation’s pipeline networks are also widespread, running alternately through remote and densely populated regions, some above ground, some below; consequently, these systems are vulnerable to accidents and terrorist attack. The 2006 partial shutdown of the Prudhoe Bay, AK, oil field due to pipeline leaks, and the 2010 pipeline accidents in San Bruno, CA, and Marshall, MI, have demonstrated this vulnerability and have heightened congressional concern about pipeline risks.

The federal program for pipeline safety resides primarily within the Department of Transportation (DOT), although its inspection and enforcement activities rely heavily upon partnerships with state pipeline safety agencies. The federal pipeline security program began with the DOT as well, immediately after the terror attacks of September 11, 2001, but pipeline security authority was subsequently transferred to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) when the latter department was created. The DOT and DHS have distinct missions, but they cooperate to protect the nation’s pipelines. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission is not operationally involved in pipeline safety or security, but it can examine safety issues under its siting authority for interstate natural gas pipelines, and can allow pipeline companies under its rate jurisdiction to recover pipeline security costs. Collectively, these agencies administer a comprehensive and complex set of regulatory authorities which has been changing significantly over the last decade and continues to do so.

Safety and Security in the Pipeline Industry

Of the nation’s approximately half million miles of transmission pipeline, roughly 170,000 miles carry hazardous liquids—over 75% of the nation’s crude oil and around 60% of its refined petroleum products, along with other products.2 Within this network, there are nearly 200 interstate crude oil and liquid fuel pipelines, which account for roughly 80% of total pipeline mileage and transported volume.3

The U.S. natural gas pipeline network consists of around 217,000 miles of interstate transmission, and 89,000 miles of intrastate transmission.4 It also contains some 20,000 miles of field and gathering pipeline, which connect gas extraction wells to processing facilities.5 Around 120 systems make up the interstate gas transmission network; another 90 or so systems operate strictly within individual states.6 These interstate and intrastate gas transmission pipelines feed around 1.2 million miles of regional pipelines in some 1,400 local distribution networks.7 Natural gas pipelines also connect to 113 liquefied natural gas (LNG) storage sites, which augment pipeline gas supplies during peak demand periods.8

Pipeline Safety Record

Taken as a whole, releases from pipelines cause few annual fatalities compared to other product transportation modes. According to the Department of Transportation (DOT), hazardous liquid pipelines reported an average of 2.4 deaths per year from 2005 through 2009. During the same period, natural gas transmission and distribution pipelines reported an average of 1.0 and 10.4 deaths per year, respectively.9 Accidental pipeline releases result from a variety of causes, including third-party excavation, corrosion, mechanical failure, control system failure, and operator error. Natural forces, such as floods and earthquakes, can also damage pipelines. There were 102 hazardous liquid pipeline accidents, 84 natural gas transmission (including gathering) pipeline accidents, and 1,608 natural gas distribution accidents in 2009.10

Although pipeline releases have caused relatively few fatalities in absolute numbers, a single pipeline accident can be catastrophic in terms of deaths and environmental damage. Notable pipeline accidents in recent years include:

- 1999?A gasoline pipeline explosion in Bellingham, WA, killed two children and an 18-year-old man, and caused $45 million in damage to a city water plant and other property.

- 2000?A natural gas pipeline explosion near Carlsbad, NM, killed 12 campers, including 4 children.

- 2006?Corroded pipelines on the North Slope of Alaska leaked over 200,000 gallons of crude oil in an environmentally sensitive area and temporarily shut down Prudhoe Bay oil production.

- 2007?An accidental release from a propane pipeline and subsequent fire near Carmichael, Mississippi killed 2 people, injured several others, destroyed 4 homes, and burned over 70 acres of grassland and woodland.

- 2010?A pipeline spill in Marshall, Michigan released 819,000 gallons of crude oil into a tributary of the Kalamazoo River.

- 2010—A natural gas pipeline explosion in San Bruno, California, killed 8 people (including 1 child), injured 60 others, and destroyed 37 homes.

Such accidents have generated persistent scrutiny of pipeline regulation and have increased state and community activity related to pipeline safety.11

Pipeline Security Risks

In addition to their vulnerability to accidents, pipelines may also be intentionally damaged by vandals and terrorists. Some pipelines may also be vulnerable to “cyber-attacks” on computer control systems or attacks on electricity grids and telecommunications networks.12 Oil and gas pipelines, globally, have been a favored target of terrorists, militant groups, and organized crime. In Colombia, for example, rebels have bombed the Caño Limón oil pipeline and other pipelines over 950 times since 1993.13 In 1996, London police foiled a plot by the Irish Republican Army to bomb gas pipelines and other utilities across the city.14 Militants in Nigeria have repeatedly attacked pipelines and related facilities, including the simultaneous bombing of three oil pipelines in May 2007.15 A Mexican rebel group similarly detonated bombs along Mexican oil and natural gas pipelines in July and September 2007.16 In June 2007, the U.S. Department of Justice arrested members of a terrorist group planning to attack jet fuel pipelines and storage tanks at the John F. Kennedy (JFK) International Airport in New York.17 Natural gas pipelines in British Columbia, Canada, were bombed six times between October 2008 and July 2009 by unknown perpetrators.18 In 2009, the Washington Post reported that over $1 billion of crude oil had been stolen directly from Mexican pipelines by organized criminals and drug cartels.19

Since September 11, 2001, federal warnings about Al Qaeda have mentioned pipelines specifically as potential terror targets in the United States.20 One U.S. pipeline of particular concern, and with a history of terrorist and vandal activity, is the Trans Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS), which transports crude oil from Alaska’s North Slope oil fields to the marine terminal in Valdez. TAPS runs some 800 miles and delivers nearly 17% of United States domestic oil production.21 In 1999, Vancouver police arrested a man planning to blow up TAPS for personal profit in oil futures.22 In 2001, a vandal’s attack on TAPS with a high-powered rifle forced a twoday shutdown and caused extensive economic and ecological damage.23 In January 2006, federal authorities acknowledged the discovery of a detailed posting on a website purportedly linked to Al Qaeda that reportedly encouraged attacks on U.S. pipelines, especially TAPS, using weapons or hidden explosives.24 In November 2007 a U.S. citizen was convicted of trying to conspire with Al Qaeda to attack TAPS and a major natural gas pipeline in the eastern United States.25 To date, there have been no known Al Qaeda attacks on TAPS or other U.S. pipelines, but such attacks remain a possibility.

Pipelines and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration

The Natural Gas Pipeline Safety Act of 1968 (P.L. 90-481) and the Hazardous Liquid Pipeline Act of 1979 (P.L. 96-129) are two of the principal early acts establishing the federal role in pipeline safety. Under both statutes, the Transportation Secretary is given primary authority to regulate key aspects of interstate pipeline safety: design, construction, operation and maintenance, and spill response planning. Pipeline safety regulations are covered in Title 49 of the Code of Federal Regulations.26 The DOT administers pipeline regulations through the Office of Pipeline Safety (OPS) within the Pipelines and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA). The OPS is funded for 206 full-time equivalent staff in 2010, based in Washington, DC; Atlanta; Kansas City; Houston; and Denver.27 This includes funding for 137 inspectors, although the agency actually employed 110 inspectors as of September 15, 2010.28 In addition to its own staff, PHMSA’s enabling legislation allows the agency to delegate authority to intrastate pipeline safety offices, and allows state offices to act as “agents” administering interstate pipeline safety programs (excluding enforcement) for those sections of interstate pipelines within their boundaries.29 Over 400 state pipeline safety inspectors are available in 2010.

PHMSA’s pipeline safety program is funded primarily by user fees assessed on a per-mile basis on each regulated pipeline operator (49 U.S.C. § 60107). P.L. 109-468 authorized annual pipeline safety program expenditures of $79.0 million in FY2007, $86.2 million in FY2008, $91.5 million in FY2009, and $96.5 million in FY2010. The President’s FY2010 budget request included $105.2 million for pipeline safety.30 The FY2011 budget requested $111.1 million.31 H.R. 5850 and S. 3644 would appropriate $111.1 million to fund the PHMSA pipeline safety program for FY2011. S. 3856 would authorize annual pipeline safety program expenditures of $111.1 million in FY2011, $115.8 million in FY2012, $119.9 million in FY2013, and $122.8 million in FY2014. The bill would also authorize $2.0 million annually through FY2014 for grants to state pipeline damage prevention programs.

PHMSA uses a variety of strategies to promote compliance with its safety standards. The agency conducts programmatic inspections of management systems, procedures, and processes; conducts physical inspections of facilities and construction projects; investigates safety incidents, and maintains a dialogue with pipeline operators. The agency clarifies its regulatory expectations through published protocols and regulatory orders, guidance manuals, and public meetings. PHMSA relies upon a range of enforcement actions, including administrative actions such as corrective action orders (CAOs) and civil penalties, to ensure that operators correct safety violations and take measures to preclude future safety problems. From 2005 through 2009, PHMSA initiated approximately 1,300 enforcement actions against pipeline operators.32 Civil penalties assessed by PHMSA for safety violations during this period totaled approximately $27.2 million.33 PHMSA also conducts accident investigations and system-wide reviews focusing on high-risk operational or procedural problems and areas of the pipeline near sensitive environmental areas, high-density populations, or navigable waters.

Since 1997, PHMSA has increasingly required industry’s implementation of “integrity management” programs on pipeline segments near “high consequence areas.” Integrity management provides for continual evaluation of pipeline condition; assessment of risks to the pipeline; inspection or testing; data analysis; and followup repair, as well as preventive or mitigative actions. High consequence areas include population centers, commercially navigable waters, and environmentally sensitive areas, such as drinking water supplies or ecological reserves. The integrity management approach directs priority resources to locations of highest consequence rather than applying uniform treatment to the entire pipeline network. PHMSA made integrity management programs mandatory for most oil pipeline operators with 500 or more miles of regulated pipeline as of March 31, 2001 (49 C.F.R. § 195).

Pipeline Safety Improvement Act of 2002

On December 12, 2002, President Bush signed into law the Pipeline Safety Improvement Act of 2002 (P.L. 107-355). The act strengthened federal pipeline safety programs, state oversight of pipeline operators, and public education regarding pipeline safety.34 Among other provisions, P.L. 107-355 required operators of regulated natural gas pipelines in high-consequence areas to conduct risk analysis and implement integrity management programs similar to those required for oil pipelines.35 The act authorized the DOT to order safety actions for pipelines with potential safety problems and increased violation penalties. The act streamlined the permitting process for emergency pipeline restoration by establishing an interagency committee, including the DOT, the Environmental Protection Agency, United States, the Bureau of Land Management, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, and other agencies, to ensure coordinated review and permitting of pipeline repairs. The act required DOT to study ways to limit pipeline safety risks from population encroachment and ways to preserve environmental resources in pipeline rights-of-way. P.L. 107-355 also included provisions for public education, grants for community pipeline safety studies, “whistle blower” and other employee protection, employee qualification programs, and mapping data submission.

Pipeline Inspection, Protection, Enforcement, and Safety Act of 2006

On December 29, 2006, President Bush signed into law the Pipeline Inspection, Protection, Enforcement and Safety Act of 2006 (PIPES Act, P.L. 109-468). The main provisions of the act address pipeline damage prevention, integrity management, corrosion control, and enforcement transparency. The PIPES act created a national focus on pipeline damage prevention through grants to states for improving damage prevention programs, establishing 811 as national “call before you dig” one-call telephone number, and giving PHMSA limited “backstop” authority to conduct civil enforcement against one-call violators in states that have failed to conduct such enforcement. The act mandated the promulgation by PHMSA of minimum standards for integrity management programs for natural gas distribution pipelines.36 It also mandated a review of the adequacy of federal pipeline safety regulations related to internal corrosion control, and required PHMSA to increase the transparency of enforcement actions by issuing monthly summaries, including violation and penalty information, and a mechanism for pipeline operators to make response information available to the public.

DOT Pipeline Security Activities

Presidential Decision Directive 63 (PDD-63), issued during the Clinton administration, assigned lead responsibility for pipeline security to the DOT.37 These responsibilities fell to the OPS, at that time a part of the DOT’s Research and Special Programs Administration (RSPA), since the agency was already addressing some elements of pipeline security in its role as safety regulator.38 In 2002, the OPS conducted a vulnerability assessment to identify critical pipeline facilities and worked with industry groups and state pipeline safety organizations “to assess the industry’s readiness to prepare for, withstand and respond to a terrorist attack....”39 Together with the Department of Energy and state pipeline agencies, the OPS promoted the development of consensus standards for security measures tiered to correspond with the five levels of threat warnings issued by the Office of Homeland Security.40 The OPS also developed protocols for inspections of critical facilities to ensure that operators implemented appropriate security practices. To convey emergency information and warnings, the OPS established a variety of communication links to key staff at the most critical pipeline facilities throughout the country. The OPS also began identifying near-term technology to enhance deterrence, detection, response, and recovery, and began seeking to advance public and private sector planning for response and recovery.41

On September 5, 2002, the OPS circulated formal guidance developed in cooperation with the pipeline industry associations defining the agency’s security program recommendations and implementation expectations. This guidance recommended that operators identify critical facilities, develop security plans consistent with prior trade association security guidance, implement these plans, and review them annually.42 Although the guidance was voluntary, the OPS expected compliance and informed operators of its intent to begin reviewing security programs within 12 months, potentially as part of more comprehensive safety inspections.43 Federal pipeline security authority was subsequently transferred outside of DOT, however, as discussed below, so the OPS did not follow through on a national program of pipeline security program reviews.

Transportation Security Administration

In November 2001, President Bush signed the Aviation and Transportation Security Act (P.L. 107- 71) establishing the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) within the DOT. According to TSA, the act placed the DOT’s pipeline security authority (under PDD-63) within TSA. The act specified for TSA a range of duties and powers related to general transportation security, such as intelligence management, threat assessment, mitigation, security measure oversight and enforcement, among others. On November 25, 2002, President Bush signed the Homeland Security Act of 2002 (P.L. 107-296) creating the Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

Among other provisions, the act transferred to DHS the Transportation Security Administration from the DOT (§ 403). On December 17, 2003, President Bush issued Homeland Security Presidential Directive 7 (HSPD-7), clarifying executive agency responsibilities for identifying, prioritizing, and protecting critical infrastructure.44 HSPD-7 maintains DHS as the lead agency for pipeline security (par. 15), and instructs the DOT to “collaborate in regulating the transportation of hazardous materials by all modes (including pipelines)” (par. 22h). The order requires that DHS and other federal agencies collaborate with “appropriate private sector entities” in sharing information and protecting critical infrastructure (par. 25). TSA joined both the Energy Government Coordinating Council and the Transportation Government Coordinating Council under provisions in HSPD-7. The missions of the councils are to work with their industry counterparts to coordinate critical infrastructure protection programs in the energy and transportation sectors, respectively, and to facilitate the sharing of security information.

HSPD-7 also required DHS to develop a national plan for critical infrastructure and key resources protection (par. 27), which the agency issued in 2006 as the National Infrastructure Protection Plan (NIPP). The NIPP, in turn, required each critical infrastructure sector to develop a Sector Specific Plan (SSP) that describes strategies to protect its critical infrastructure, outlines a coordinated approach to strengthen its security efforts, and determines appropriate funding for these activities. Executive Order 13416 further required the transportation sector SSP to prepare annexes for each mode of surface transportation.45 In accordance with the above requirements the TSA issued its Transportation Systems Sector Specific Plan and Pipeline Modal Annex in 2007.

TSA Pipeline Security Activities

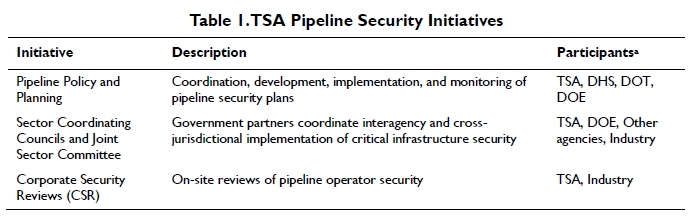

Pipeline security activities at TSA are led by the Pipeline Security Division (PSD) within the agency’s Office of Transportation Sector Network Management.46 According to the agency’s Pipeline Modal Annex (PMA), TSA has been engaged in a number of specific pipeline security initiatives since 2003 as summarized in Table 1.

In 2003, TSA initiated its Corporate Security Review (CSR) program, wherein the agency visits the largest pipeline and natural gas distribution operators to review their security plans and inspect their facilities. During the reviews, TSA evaluates whether each company is following the intent of the OPS security guidance, and seeks to collect the list of assets each company had identified meeting the criteria established for critical facilities. In 2004, the DOT reported that the plans reviewed to date (approximately 25) had been “judged responsive to the OPS guidance.”47 As of August 2010, TSA had completed CSR’s covering the largest 100 pipeline systems (84% of total U.S. energy pipeline throughput) and was in the process of conducting second CSR’s of these systems.48 According to TSA, CSR results indicate that the majority of U.S. pipeline systems “continue to do a good job in regards to pipeline security” although there are areas in which pipeline security can be improved.49 Past CSR reviews have identified inadequacies in some company security programs such as not updating security plans, lack of management support, poor employee involvement, inadequate threat intelligence, and employee apathy or error.50 In 2008, the TSA initiated its Critical Facility Inspection Program (CFI), under which the agency conducts in-depth inspections of all the critical facilities of the 100 largest pipeline systems in the United States. By the end of 2011, TSA expects to complete CFIs for all 373 critical facilities identified by pipeline operators.51

In addition to the initiatives in Table 1, TSA has worked to establish qualifications for personnel applying for positions with unrestricted access to critical pipeline assets and has developed its own inventory of critical pipeline infrastructure.52 The agency has also addressed legal issues regarding recovery from terrorist attacks, such as FBI control of crime scenes and eminent domain in pipeline restoration. In October 2005, TSA issued an overview of recommended security practices for pipeline operators “for informational purposes only ... not intended to replace security measures already implemented by individual companies.”53 The agency released revised guidance on security best practices at the end of 2006, and is currently reviewing an updated version for possible release in 2011. The guidelines include a section on cybersecurity developed with the assistance of the Applied Physics Laboratory of John Hopkins University as well as other government and industry stakeholders.54

The mission of TSA’s Pipeline Security Division (PSD) currently includes developing security standards; implementing measures to mitigate security risk; building and maintaining stakeholder relations, coordination, education and outreach; and monitoring compliance with security standards, requirements, and regulations. The President’s FY2011 budget request for DHS does not include a separate line item for TSA’s pipeline security activities. The budget request does include a $137.6 million line item for “Surface Transportation Security,” which encompasses security activities in [transportation] modes, including pipelines.55 The PSD has traditionally received from the agency’s general operational budget an allocation for routine operations such as regulation development, travel, and outreach. According to the PSD, the budget funds 13 full-time equivalent staff within the office.56

In 2007 the TSA Administrator testified before Congress that the agency intended to conduct a pipeline infrastructure study to identify the “highest risk” pipeline assets, building upon such a list developed through the CSR program. He also stated that the agency would use its ongoing security review process to determine the future implementation of baseline risk standards against which to set measurable pipeline risk reduction targets.57 Provisions in the Implementing Recommendations of the 9/11 Commission Act of 2007 (P.L. 110-53) require TSA, in consultation with PHMSA, to develop a plan for the federal government to provide increased security support to the “most critical” pipelines at high or severe security alert levels and when there is specific security threat information relating to such pipeline infrastructure (§ 1558(a)(1)). The act also requires a recovery protocol plan in the event of an incident affecting the interstate and intrastate pipeline system (§ 1558(a)(2)). According to TSA, a draft plan has been completed and is currently under review in the TSA/DHS clearance process.58

Security Incident Investigations

In addition to the above pipeline security initiatives, the TSA Pipeline Security Division has performed a limited number of vulnerability assessments and has supported investigations for specific companies and assets where intelligence information has suggested potential terrorist activity. The PSD, along with PHMSA, was involved in the investigation of an August 2006 security breach at an LNG peak-shaving plant in Lynn, MA.59 Although not a terrorist incident, the security breach involved the penetration of intruders through several security barriers and alert systems, permitting them to access the main LNG storage tank at the facility. The PSD also became aware of the JFK airport terrorist plot in its early stages and supported the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s associated investigation. The PSD engaged the private sector in helping to assess potential targets and determine potential consequences. The PSD worked with the pipeline company to keep it informed about the plot, discuss its security practices, and review its emergency response plans.60

GAO Study of TSA’s Pipeline Security Activities

In December 2008, the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation requested a study by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) examining TSA’s efforts to ensure pipeline security. GAO’s report, released in August 2010, focused on TSA’s use of risk assessment and risk information in securing pipelines, actions the agency has taken to improve pipeline security under guidance in the 9/11 Commission Act of 2007 (P.L. 110-53), and the agency’s efforts to measure such security improvement efforts.61 Among other findings, GAO concluded that, although TSA had begun to implement a risk management approach to prioritize its pipeline security efforts, work remained to ensure that the highest risk pipeline systems would get the necessary scrutiny. GAO also concluded that TSA was missing opportunities under its CSR and CFI programs to better ensure that pipeline operators understand how they can enhance the security of their pipeline systems. TSA could also make better use of CSR and CFI recommendations for analyzing pipeline vulnerabilities and was not following up on these recommendations. GAO found that linking TSA’s pipeline security performance measures and milestones to the goals and objectives in its national security strategy for pipeline systems could aid in achieving results within specific time frames and could facilitate more effective oversight and accountability.62 TSA concurred with all of GAO’s recommendations for addressing the issues and is in the process of implementing them.63

Federal Energy Regulatory Commission

One area related to pipeline safety and security not under either PHMSA’s or TSA’s primary jurisdiction is the siting approval of new gas pipelines, which is the responsibility of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). Companies building interstate natural gas pipelines must first obtain from FERC certificates of public convenience and necessity. (FERC does not oversee oil pipeline construction.) FERC must also approve the abandonment of gas facility use and services. These approvals may include safety and security provisions with respect to pipeline routing, safety standards and other factors.64 As a practical matter, however, FERC has traditionally left these considerations to the other agencies.65

On September 14, 2001, FERC notified jurisdictional companies that it would “approve applications proposing the recovery of prudently incurred costs necessary to further safeguard the nation’s energy systems and infrastructure” in response to the terror attacks of 9/11. FERC also committed to “expedite the processing on a priority basis of any application that would specifically recover such costs from wholesale customers.” Companies could propose a surcharge over currently existing rates or some other cost recovery method.66 In FY2005, the commission processed security cost recovery requests from 14 oil pipelines and 3 natural gas pipelines.67 FERC’s FY2006 annual report stated that “the Commission continues to give the highest priority to deciding any requests made for the recovery of extraordinary expenditures to safeguard the reliability and security of the Nation’s energy transportation systems and energy supply infrastructure.”68 FERC’s subsequent annual reports do not mention pipeline security.

In February 2003, FERC promulgated a new rule (RM02-4-000) to protect critical energy infrastructure information (CEII). The rule defines CEII as information that “must relate to critical infrastructure, be potentially useful to terrorists, and be exempt from disclosure under the Freedom of Information Act.” According to the rule, critical infrastructure is “existing and proposed systems and assets, whether physical or virtual, the incapacity or destruction of which would negatively affect security, economic security, public health or safety, or any combination of those matters.” CEII excludes “information that identifies the location of infrastructure.” The rule also establishes procedures for the public to request and obtain such critical information, and applies both to proposed and existing infrastructure.69

On May 14, 2003, FERC handed down new rules (RM03-4) facilitating the restoration of pipelines after a terrorist attack. The rules allow owners of a damaged pipeline to use blanket certificate authority to immediately start rebuilding, regardless of project cost, even outside existing rights-of-way. Pipeline owners would still need to notify landowners and comply with environmental laws. Prior rules limited blanket authority to $17.5 million projects and 45-day advance notice.70

National Transportation Safety Board

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) is an independent federal agency charged with determining the probable cause of transportation accidents (including pipeline accidents), promoting transportation safety, and assisting accident victims and their families. The board’s experts investigate significant accidents, develop factual records, and issue safety recommendations to prevent similar accidents from recurring. The NTSB has no statutory authority to regulate transportation, however, so its safety recommendations to industry or government agencies are not mandatory. Nonetheless, because of the board’s strong reputation for thoroughness and objectivity, the average acceptance rate for its safety recommendations is over 80%.70a

San Bruno Pipeline Accident Investigation

In August 2011, the NTSB issued preliminary findings and recommendations from its investigation of the San Bruno Pipeline accident. The investigation included testimony from pipeline company officials, government agency officials (PHMSA, state, and local), as well as testimony from other pipeline experts and stakeholders. In addition to specifics about the San Bruno incident, the hearing addressed more general pipeline issues, including public awareness initiatives, pipeline technology, and oversight of pipeline safety by federal and state regulators.70b

The NTSB’s findings were highly critical of the pipeline operator (PG&E) as well as both the state and federal pipeline safety regulators. The board concluded that “the multiple and recurring deficiencies in PG&E operational practices indicate a systemic problem” with respect to its pipeline safety program.70c The board further concluded that

the pipeline safety regulator within the state of California, failed to detect the inadequacies in PG&E’s integrity management program and that the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration integrity management inspection protocols need improvement. Because the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration has not incorporated the use of effective and meaningful metrics as part of its guidance for performance-based management pipeline safety programs, its oversight of state public utility commissions regulating gas transmission and hazardous liquid pipelines could be improved.

In her opening statement about the San Bruno accident report, NTSB Chairman Hersman summarized the board’s findings as “troubling revelations … about a company that exploited weaknesses in a lax system of oversight and government agencies that placed a blind trust in operators to the detriment of public safety.”70d The NTSB’s final accident report “concludes that PHMSA’s enforcement program and its monitoring of state oversight programs have been weak and have resulted in the lack of effective Federal oversight and state oversight.”70e The NTSB issued 39 recommendations stemming from its San Bruno accident investigation, including 20 recommendations to the Secretary of Transportation and PHMSA. These recommendations included:

- Conducting audits to assess the effectiveness of PHMSA’s oversight of performance-based pipeline safety programs and state pipeline safety program certification,

- Requiring pipeline operators to provide system-specific information to the emergency response agencies of the communities in which pipelines are located,

- Requiring that automatic shutoff valves or remote control valves be installed in high consequence areas and in class 3 and 4 locations,70f

- Requiring that all natural gas transmission pipelines constructed before 1970 be subjected to a hydrostatic pressure test that incorporates a spike test,

- Requiring that all natural gas transmission pipelines be configured so as to accommodate internal inspection tools, with priority given to older pipelines, and

- Revising PHMSA’s integrity management protocol to incorporate meaningful metrics, set performance goals for pipeline operators, and require operators to regularly assess the effectiveness of their programs using meaningful metrics.70g

More detailed discussion of the accident findings and the NTSB’s recommendations are publicly available in the final accident report.

Key Policy Issues

The U.S. CongressCongress is considering federal pipeline safety program reauthorization as well as numerous new legislative proposals following major pipeline accidents in 2010 and 2011. In the context of its broader oversight of federal pipeline safety and security activities, and in addition to the findings of the NTSB’s San Bruno investigation, Congress may examine certain key issues which have drawn particular attention in recent policy deliberations.

Staffing Resources for Pipeline Safety and Security

The U.S. pipeline safety program is based upon on a combination of federal and state staff to implement and enforce federal pipeline safety regulations. To date, PHMSA has relied heavily on state agencies for pipeline inspections, with only 20% of inspectors in 2010 being federal employees. Some in Congress have criticized this level of inspector staffing at PHMSA as being insufficient to adequately cover pipelines under the agency’s jurisdiction, notwithstanding state agency cooperation. The Strengthening Pipeline Safety and Enforcement Act of 2011 (S. 234)

would increase the number of full-time equivalent employees at PHMSA by at least 100 in increments of 25 annually between FY2011 and FY2014 (§3(a)). S. 275 and H.R. 2937 would increase PHMSA pipeline safety staffing by 39 through FY2014. In considering such PHMSA staff increases, three distinct issues that may warrant further consideration are the overall number of federal inspectors, the agency’s historical use of staff funding, and the staffing of pipeline safety inspectors among the states.

PHMSA Inspectors

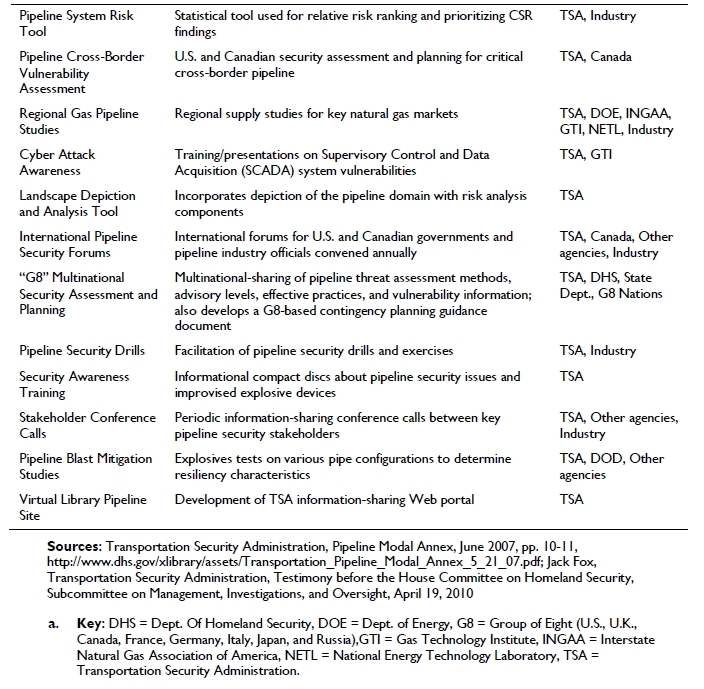

The President’s FY2012 budget request listed PHMSA’s estimated staffing in 2011 under the continuing resolution as 206 full-time equivalent employees (FTEs). The budget request would fund an estimated 225 FTEs in 2011.71 As Figure 1 shows, the addition of 100 staff (as proposed in S. 234) would increase the DOT’s overall pipeline safety staff by approximately 50% over current levels, and would represent a nearly 300% increase in funded staff since 2001. Thus, staff increases under that proposal would be a continuation of staff growth (of mostly inspectors) begun 10 years ago in response to the 1999 Bellingham accident, the terrorist attacks of 9/11, implementation of PHMSA’s integrity management regulations, and the continued growth of U.S. pipelines.

Whether 300 PHMSA pipeline safety staff in 2014 would be the optimal number is open to debate. However, the additional employees available under proposed legislation would not necessarily all be field inspectors, as inspectors are only one of several categories of hiring “focus” for the agency listed under these bills.

PHMSA Staffing Shortfalls

One issue that complicates the PHMSA staffing debate is a long-term pattern of understaffing in the agency’s pipeline safety program. At least as far back as 1994, PHMSA’s (or RSPA’s) actual staffing for pipeline safety as reported in each of its annual budgets requests has fallen short of the level of staffing anticipated in the prior year’s budget request. For example, the president’s FY2011 budget request for pipeline safety reports 175 actual employees in 2009. However, the FY2010 budget request stated an expectation of 191 employees (“estimated”) for 2009. On this basis, between 2001 and 2009, the agency reported a staffing shortfall averaging approximately 24 employees every year. (Note that, due to this annual shortfall, the FTEs reported in Figure 1 are higher than the number actually employed by PHMSA.) In testimony before Congress in September 2010, DOT officials reported that PHMSA employed only 110 of 137 inspectors for which it was funded—a shortfall of 27 inspectors.72 In March 2011, agency officials reported 126 inspectors employed.72 As of September 13, 2011, there were no vacancies posted for a PHMSA pipeline safety inspector position at the USAJobs website.

PHMSA officials offer a number of reasons for the persistent shortfall in inspector staffing. These reasons include a scarcity of qualified inspector job applicants, delays in the federal hiring process during which applicants accept other job offers, and PHMSA inspector turnover— especially to pipeline companies which often hire away PHMSA inspectors for their corporate safety programs. Because PHMSA pipeline inspectors are highly trained by the agency (typically for two years before being allowed to operate independently) they are highly valued by pipeline operators seeking to comply with federal safety regulations. PHMSA officials also cite structural issues associated with the agency’s appropriations which can require the use of FTE salary funding to meet other obligations.73 The pipeline safety staffing shortfall raises the question of how the DOT will achieve and maintain a sharply increased inspection workforce under proposed legislation when it has not been able to staff the number of inspectors for which it is already budgeted.

State Pipeline Inspector Funding

Because state agencies would continue to account for the majority of U.S. pipeline safety inspectors, even if proposed legilation were enacted, another important consideration is how the number of state inspectors might be affected by budget shortfalls and possible agency funding cuts faced by many states due to the recent U.S. economic recession. Under P.L. 109-468 (§ 2(c)), PHMSA is authorized to award grants reimbursing state governments for up to 80% of the cost of the staff, personnel, and activities required to support the federal pipeline safety program (although reimbursement has not reached the 80% level since the passage of the act). According to DOT these grant are essential to “enable the states to continue their current programs and hire additional inspectors... [and] assure that states do not turn over responsibility for distribution pipeline systems to the Federal inspectors,” among other reasons.74 Notwithstanding these federal grants, inspector staffing at state pipeline safety agencies has been negatively affected by state budget deficits. According to the National Association of Pipeline Safety Representatives, pipeline safety employees in 17 states have been furloughed without pay for up to three weeks.75 PHMSA officials have also reportedly cited unfilled positions among state pipeline safety agencies as eroding the state pipeline safety workforce.76 Senior DOT officials consider financial problems among state pipeline safety agencies a matter of “great concern” and have granted to states waivers from certain regulatory financial requirements to increase their access to federal grant money.77 Nonetheless, the future availability of state pipeline safety inspectors remains uncertain. In particular, the possibility that some states may choose to end their roles as agents for the federal pipeline safety program—or that states may lose federal pipeline safety program certification for performance reasons—and thereby shift a greater burden for pipeline inspections back to the federal government, may require continued attention from Congress.

TSA Pipelines Security Resources

Similar to its concerns about the adequacy of federal pipeline safety staffing, Congress has long been concerned about staff resources available to implement the nation’s pipeline security program. For example, as one Member remarked in 2005, “aviation security has received 90% of TSA’s funds and virtually all of its attention. There is simply not enough being done to address ... pipeline security.”78 At a congressional field hearing in April 2010, another Member expressed concern that TSA’s pipeline division did not have sufficient staff to carry out a federal pipeline security program on a national scale.79

At its current staffing level of 13 FTEs, TSA’s Pipelines Security Division has limited field presence. In conducting a pipeline corporate security review, for example, TSA typically sends one to three staff to hold a three- to four-hour interview with the operator’s security representatives followed by a visit to only one or two of the operator’s pipeline assets.80 TSA’s plan to focus security inspections on the largest pipeline and distribution system operators tries to make the best use of its limited resources. However, there are questions as to whether the agency’s CSRs as currently structured allow for rigorous security plan verification and a credible threat of enforcement. The limited number of CSRs the agency can complete in a year is a particular concern. According to a 2009 GAO report, “TSA’s pipeline division stated that they would like more staff in order to conduct its corporate security reviews more frequently,” and “analyzing secondary or indirect consequences of a terrorist attack and developing strategic risk objectives required much time and effort.”81 P.L. 110-53 specifically authorized funding of $2 million annually through FY2010 for TSA’s pipeline security inspections and enforcement program (§ 1557(e)). It is an open question whether $2 million annually is sufficient to enable TSA to meet congressional expectations for federal pipeline security activities.

Since both PHMSA and TSA have played important roles in the federal pipeline security program, with TSA the designated lead agency since 2002, Congress has raised questions about the appropriate responsibilities and division of pipeline security authority between them.82 According to TSA, the two agencies “continue to enjoy a 24/7 communication and coordination relationship in regards to all pipeline security and safety incidents.”83 Nonetheless, given the limited staff in TSA’s pipeline security division, and the comparatively large pipeline safety staff (especially inspectors) in PHMSA, legislators have considered whether the TSA-PHMSA pipeline security relationship optimally aligns staff resources across both agencies to fulfill the nation’s overall pipeline safety and security mission.84 The Transportation Security Administration Authorization Act of 2011 reported by the House Committee on Homeland Security’s Subcommittee on Transportation Security on September 14, 2011, would mandate a study regarding the relative roles and responsibilities of the Department of Homeland Security and the Department of Transportation with respect to pipeline security (§ 325).84a

Automatic Shutoff Valves for Transmission Pipelines

In the 2010 San Bruno pipeline accident, natural gas continued to flow from the pipeline for nearly two hours after the initial explosion—fueling the intense fire, hindering emergency response, and increasing damage caused by the fire. The long duration of flowing gas reportedly was due to delays in the closing of manually operated valves by the pipeline operator, and may have been exacerbated by inadequate employee training in valve closure procedures.85

Consequently, some advocates have called for widespread installation of remotely or automatically controlled valves in natural gas and hazardous liquids transmission pipelines. As noted earlier, the NTSB has recommended the installation of such valves in all “high consequence” and relatively more populated areas. S. 234 would require the installation of remotely or automatically controlled valves capable of “shutting off the flow of gas” in natural gas pipelines “wherever technically and economically feasible” (§6). The Pipeline Safety and Community Empowerment Act of 2011 (H.R. 22) would require the installation of “automatic or remote shut off valves” for all new transmission pipelines and for existing transmission pipelines near significant earthquake faults or in relatively populated areas (§6). S. 275 would require automatic or remotely controlled shut off valves “where economically and technically feasible” for all new transmission pipelines (§5). H.R. 2937 contains a similar requirement and would mandate a study of retrofit installations in high consequence areas (§ 5). The Pipeline Safety, Regulatory Certainty, and Job Creation Act of 2011 (H.R. 2845) would authorize “if determined appropriate ... the use of automatic or remotecontrolled shut-off valves, or equivalent technology, where economically, technically, and operationally feasible” for all new transmission pipelines (§ 4).

Previous Consideration

The possibility of requiring remotely controlled or automatic shut off valves for natural gas pipelines is not new. Congress previously considered such requirements in reaction to a 1994 natural gas pipeline fire in Edison, NJ, similar to the San Bruno accident in which it took the pipeline operator 2½ hours to close its manually operated valves.86 In 1995, during the 104th Congress, H.R. 432 and S. 162 would have required the installation of remotely or automatically controlled valves in natural gas pipelines “wherever technically and economically feasible” (§ 11). Under the Accountable Pipeline Safety and Partnership Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-304), Congress mandated a DOT assessment of remotely controlled valves (RCVs) on interstate natural gas pipelines, and empowered the agency to require such valves if appropriate based upon its findings (§4(h)).

The DOT’s assessment, released in 1999, reported that installation of RCVs would provide only “a small benefit from reduced casualties because virtually all casualties from a rupture occur before an RVC could be activated.”87 Moreover, the DOT reported that it lacked data to compare pipeline fire property damage with and without RCVs. Nonetheless, the DOT study advocated the deployment of RCVs, at least in some gas pipeline locations.

We have found that RCVs are effective and technically feasible, and can reduce risk, but are not economically feasible. We have also found that there may be a public perception that RCVs will improve safety and reduce the risk from a ruptured gas pipeline. We believe there is a role for RCVs in reducing the risk from certain ruptured pipelines and thereby minimizing the consequences of certain gas pipeline ruptures.... Any fire would be of greater intensity and would have greater potential for damaging surrounding infrastructure if it is constantly replenished with gas. The degree of disruption in heavily populated and commercial areas would be in direct proportion to the duration of the fire. Although we lack data enabling us to quantify these potential consequences, we believe them to be significant nonetheless, and we believe RCVs may provide the best means for addressing them.88 Notwithstanding this conclusion, the DOT has not mandated the use of RCVs in natural gas transmission pipelines.

The natural gas pipeline industry historically has objected to federal mandates to install remotely controlled or automated valves. Although pipeline operators already employ such valves under specific circumstances, such as in hard-to-access locations or at compressor stations, they have opposed the installation of such valves more widely throughout their pipeline systems on the grounds that they are usually not cost-effective. They also argue that such valves do not always function properly, would not prevent natural gas pipeline explosions (which cause most fatalities), and are susceptible to false alarms, needlessly shutting down pipelines and disrupting critical fuel supplies.89 Automatic valves, in particular, may be susceptible to unnecessary closure, potentially disrupting critical flows of natural gas to distribution utilities and—as a result—increasing safety risks associated with residential furnace relighting, among other concerns.90 Some operators also claim higher maintenance costs for valves that are not manually operated.

Remotely Controlled Valves for Liquids Pipelines

The use of remotely controlled or automatic valves has also been a long-standing consideration for hazardous liquid pipeline systems. The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) began to address the need for rapid shutdown of failed hazardous liquid pipelines using remotely controlled or automatic valves in the 1970s.91 In 1987, the NTSB recommended that the DOT “require the installation of remote-operated valves on pipelines that transport hazardous liquids, and base the spacing of remote-operated valves on the population at risk.”92 The Pipeline Safety Act of 1992 (P.L. 102-508) required the DOT to assess the effectiveness of “emergency flow restricting devices (including remotely controlled valves and check valves)” on hazardous liquid pipelines, and required the DOT to “issue regulations prescribing the circumstances under which operators of hazardous liquid pipeline facilities must use emergency flow restricting devices” (§ 212). Notwithstanding this Congressional mandate, the NTSB found the DOT’s efforts to promote the use of such devices inadequate. In 1996, the NTSB stated that the DOT “has performed studies, conducted research, and sought industry input, but has failed to carry through and develop requirements for leak detection and rapid shutdown of failed pipelines.”93 In its integrity management regulations, issued in December 2000, the DOT opted to leave the decision whether to install emergency flow restricting devices up to pipeline operators.94

Valve Replacement Costs

Cost would be a major factor in a broad national program to retrofit manual valves with remotelycontrolled or automatic valves. For example, in the interstate natural gas pipeline network, valves are typically installed every 5 to 20 miles. Assuming a 10-mile separation between valves, the nation’s 306,000 mile gas transmission system contains over 30,000 valves. The spacing of valves can be much closer together in particular pipeline systems, however, such as systems located in more populated areas. In October 2010 PG&E reported 300 valves that could be candidates for automation in approximately 565 miles of high consequence area pipelines in its California system.95

The potential costs of retrofitting manual valves vary greatly by pipeline and specific location. A 1998 Southwest Research Institute report estimated a cost of $32,000 (approximately $40,000 in 2010 dollars) per valve for retrofitting 30-inch pipeline valves to make them remotely controlled.96 The DOT’s 1999 study reported an average cost of $83,000 (approximately $100,000 in 2010 dollars) for Texas Eastern Transmission Corporation (TETCO) to retrofit 90 existing valves in a large part of its pipeline system.97 PG&E estimates the average cost of retrofitting an automatic or remotely controlled valve on an existing large diameter pipeline at approximately $750,000, but ranging as low as $100,000 and as high as $1.5 million.98

Applying, for illustration, a $100,000 cost to some 30,000 valves yields $3.0 billion in capital investment required, not counting any higher future maintenance expenses. Even if such valve retrofits were required only in heavily populated areas, industry costs could still be hundreds of millions of dollars—a significant cost to the pipeline industry and therefore likely to increase rates for pipeline transportation of natural gas. To the extent that some pipeline systems, like PG&E’s, contain more valves then others per mile of pipe, they could be disproportionately affected. Gas pipeline service interruptions would also be an issue as specific lines could be repeatedly taken out of service during the valve retrofit process. The hazardous liquids pipeline industry could face capital costs and service interruptions of the same magnitude if required to do a widespread valve retrofit on existing lines. Additional right-of-way costs, environmental impacts, and construction accidents associated with the valve replacements could also be a consideration. For new pipelines, the incremental costs of installing remotely controlled or automatic valves instead of manual valves would be lower than in the retrofit case, but could still increase future pipeline costs.

SCADA and Leak Detection System Requirements

To effectively reduce the impact of pipeline accidents, installing remotely controlled or automatic valves may require associated investments in supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) systems along with other operational changes to improve leak detection. As one pipeline expert has stated,

The pipeline operator’s focus on keeping the pipeline system operating and the lack of remotely-operable valves are the primary factors that control the quantity of product released after a rupture or leak. Even with remote control valves this relationship will not change unless the pipeline is equipped with a reliable leak detection subsystem that works with the SCADA system and [unless] those who control pipeline operations are trained for and dedicated to minimizing product release (safety and environmental mindset) rather than trained for and dedicated to keeping the system operating (economic mindset).99

In its report about a 1996 pipeline accident in Tiger Pass, LA, the NTSB similarly concluded that the operator’s “delay in recognition ... that it had experienced a pipeline rupture at Tiger Pass was due to the piping system’s dynamics during the rupture and to the design of the company’s SCADA system.”100 Consistent with these concerns, S. 3824 would mandate standards for natural gas leak detection with the goal of identifying substantial leaks in high consequence areas as expeditiously as technologically possible (§ 7). S. 3856 includes leak detection requirements for hazardous liquid pipelines (§ 10). H.R. 6295 mandates leak detection standards for both types of pipeline. Estimates of converting manual valves may, therefore, need to account for the costs of SCADA changes, leak detection systems, and associated training. These costs may also include significant reliability and security components, since increasing reliance upon new or expanded SCADA systems may also expose pipeline systems to greater risk from operating software failure or cyberterrorism.101

Consistent with the concerns above, S. 234 would mandate standards for natural gas leak detection with the goal of identifying substantial leaks in high consequence areas as expeditiously as technologically possible (§7). S. 275 (§10) and H.R. 2845 (§10) includes leak detection requirements for hazardous liquid pipelines. S. 1502 would require PHMSA to review the need for leak detection performance standards, although it does not mandate such standards (§5). H.R. 22 mandates leak detection standards for both gas and liquids pipelines. H.R. 2845 would require a DOT analysis of the technical limitations of leak detection systems as well as the feasibility of establishing standards for such systems (§8(a)). The bill would, however, prohibit standards for the capability of leak detection systems or requiring operators to use leak detection systems (§8(b)).

Public Perceptions

Some stakeholders have argued that public perceptions of improved pipeline safety and control are the highest perceived benefit of remotely controlled or automatic valves.102 Although the value of these perceptions is hard to quantify (and, therefore, not typically reflected in costeffectiveness studies), the importance of public perception and community acceptance of pipeline infrastructure can be a significant consideration in pipeline design, expansion, and regulation. In 2001, a representative of the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners testified before Congress that “the main impediment to siting energy infrastructure is the great difficulty getting public acceptance for needed facilities.”103 Likewise, the National Commission on Energy Policy stated in its 2006 report that energy-facility siting is “a major cross-cutting challenge for U.S. energy policy,” largely because of public opposition to new energy projects and other major infrastructure.104

One result of public concern about pipeline safety has been to prevent new pipeline siting in certain localities, and to increase pipeline development time and costs in others. In a 2006 report, for example, the EIA stated that “several major projects in the Northeast, although approved by FERC, have been held up because of public opposition or non-FERC regulatory interventions.”105

In the specific case of the Millennium Pipeline, proposed in 1997 to transport Canadian natural gas to metropolitan New York, developers did not receive final construction approval for nine years, largely because of community resistance to the pipeline route.106 Numerous other proposed pipelines, especially in populated areas, have faced similar public acceptance barriers.107 Even where there is federal siting authority, as is the case for interstate natural gas pipelines, community stakeholders retain many statutory and regulatory avenues to affect energy infrastructure decisions. Consequently, the public perception value of remotely controlled or automatic pipeline valves may need to be accounted for, especially with respect to its implications for general pipeline development and operations.

Natural Gas Distribution Excess Flow Valves

While the San Bruno, CA, and Edison, NJ, gas pipeline accidents have focused attention on automatic valves in large diameter transmission pipelines, this technology also applies to smaller gas distribution lines serving individual buildings. In natural gas distribution systems, “excess flow” valves are safety devices which can automatically shut off pipeline flow in the event of a leak. In this way, the valves can minimize the release of natural gas during a pipeline accident, thereby reducing the likelihood or severity of a fire or explosion. P.L. 109-468 required PHMSA to promulgate minimum standards for natural gas distribution systems requiring the installation of excess flow valves on new gas distribution lines in single-family homes (§ 9). The agency issued final regulations for excess flow valves as part of its final rule for natural gas distribution integrity management programs on December 3, 2009.108 S. 3856 would mandate excess flow valves for new or entirely replaced distribution branch pipelines, as well as service lines to multi-family residential buildings and small commercial facilities. Although smaller in scale, automatic valves in distribution lines raise the same cost and safety tradeoffs as automatic valves in large diameter pipelines.

PHMSA Penalties and Pipeline Safety Enforcement

The adequacy of the PHMSA’s enforcement strategy has been an ongoing focus of congressional oversight.109 Provisions in the Pipeline Safety Improvement Act of 2002 (P.L. 107-355) put added scrutiny on the effectiveness of the agency’s enforcement strategy and assessment of civil penalties (§ 8). In April 2006, PHMSA officials testified before Congress that the agency had institutionalized a “tough-but-fair” approach to enforcement, “imposing and collecting larger penalties, while guiding pipeline operators to enhance higher performance.”110 According to the agency, $4.6 million in proposed civil penalties in 2005 was three times greater than penalties proposed in 2003, the first year higher penalties could be imposed under P.L. 107-355 (§ 8(a)).111 Proposed penalties totaled $6.5 million in 2009.112Proposed penalties through August, 23, 2011, totaled $2.5 million, with an average penalty of approximately $63,000.113 S. 234 (§2(a)), S. 275 (§2(a)), and H.R. 2937 (§2(a)) would increase the maximum civil penalty from $1.0 million to $2.5 million for a related series of major consequence violations, such as those causing serious

injuries, deaths, or environmental harm. H.R. 2845 (§2(a)) would increase the maximum civil penalty to $1.75 million.

Although PHMSA’s imposition of pipeline safety penalties appears to have risen under P.L. 107- 355, the role of federal penalties in promoting greater operator compliance with pipeline safety regulations is not always clear. To understand the potential influence of penalties on operators, it can be helpful to put PHMSA fines in the context of the overall costs to operators of a pipeline release. Pipeline companies, seeking to generate financial returns for their owners, are motivated to operate their pipelines safely (and securely) for a range of financial reasons. While these financial considerations certainly include possible PHMSA penalties, the costs of a pipeline accident may also include fines for violations of environmental laws (federal and state), the costs of spill response and remediation, penalties from civil litigation, the value of lost product, costs for pipeline repairs and modifications (e.g., to resolve federal regulatory interventions), and other costs. Depending upon the severity of a pipeline release, these other costs may far exceed pipeline safety fines, as illustrated by the following examples.

- Kinder-Morgan. In April 2006 Kinder Morgan Energy Partners entered into a consent agreement with PHMSA to resolve a corrective action order stemming from three hazardous liquid spills in 2004 and 2005 from the company’s Pacific Operations pipeline unit.114 According to the company, the agreement would require Kinder Morgan to spend approximately $26 million on additional integrity management activities, among other requirements.115 Under a 2007 settlement agreement with the United States Justice Department and the State of California, Kinder Morgan also agreed to pay approximately $3.8 million in civil penalties for violations of environmental laws and approximately $1.5 million related to response and remediation associated with these spills. The spills collectively released approximately 200,000 gallons of diesel fuel, jet fuel, and gasoline.116 This volume of fuel would have a product value on the order of $0.5 million based on typical wholesale market prices at the time of the spills.

- Plains All American. In 2010, Plains All American Pipeline agreed to spend approximately $41 million to upgrade 10,420 miles of U.S. oil pipeline to resolve Clean Water Act (CWA) violations for 10 crude oil spills in Texas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Kansas from 2004 through 2007. Among these upgrades, the company agreed to spend at least $6 million on equipment and materials for internal corrosion control and surveys on at least 2,400 miles of pipeline. The company was required to pay $3.25 million civil penalty associated with the CWA violations.117

- Enbridge. Enbridge Energy Partners estimated expenses of $475 million to clean up two oil spills on its Lakehead pipeline system in 2010, including the spill in Marshall, MI. This estimate did not include fines or penalties which might also be imposed in connection with the spills. The pipeline operator also reported $16 million in lost revenue from pipeline shipments it could not redirect to other lines while the Lakehead system was out of service.118 The full impact of these expenditures on the company’s business is unclear, however as Enbridge stated in a subsequent quarterly report that “substantially all of the costs” related to its 2010 oil pipeline spills “will ultimately be recoverable under our existing insurance policies.”119

- Olympic Pipe Line. After the 1999 Bellingham pipeline accident, Olympic Pipe Line Company and associated defendants reportedly agreed to pay a $75 million settlement to the families of two children killed in the accident.120

- El Paso. In 2002, El Paso Corporation settled wrongful death and personal injury lawsuits stemming from the 2000 natural gas pipeline explosion near Carlsbad, NM, which killed 12 campers.121 Although the terms of those settlements were not disclosed, two additional lawsuits sought a total of $171 million in damages.122 However, El Paso’s June 2003 quarterly financial report stated that “our costs and legal exposure ... will be fully covered by insurance.”123

PHMSA Penalties in Perspective

The threat of safety enforcement penalties is often considered one of the primary tools available to pipeline safety regulators to ensure operator compliance with their safety requirements. However, as the examples above suggest, pipeline safety fines, even if they were raised to $2.5 million for major violations, could still account for only a limited share of the financial impact of future pipeline releases. So it is not clear how large an effect increasing PHMSA’s authorizedfines, alone, might have on operator compliance. On the other hand, the authority of PHMSA to influence pipeline operations directly—for example, through corrective action orders or shutdown orders in the event of a pipeline failure—can have a large financial impact on a pipeline operator in terms of capital expenditures or lost revenues. Indeed, some have suggested that this operational authority is the most influential component of PHMSA’s pipeline safety enforcement strategy. Therefore, as Congress continues its oversight of PHMSA’s enforcement activities, and considers new proposals to increase compliance with federal pipeline safety regulations, it may evaluate how PHMSA’s authorities to set standards, assess penalties, and directly affect pipeline operations may reinforce one another to improve U.S. pipeline safety.

Regulation of Canadian Oil/Tar Sands Crude Pipelines123a

Canadian oil exports to the United States have been increasing rapidly, primarily due to growing output from the oil sands in Western Canada. Oil sands (also referred to as tar sands) are a mixture of clay, sand, water, and heavy black viscous oil known as bitumen. Oil sands are processed to extract the bitumen, which can then be upgraded into a product that is suitable for pipeline transport. Canada’s oil sands production can be exported as either a light, upgraded synthetic crude (“syncrude”) or a heavy crude oil that is a blend of bitumen diluted with lighter hydrocarbons (“dilbit”) to ease transport. The bulk of oil sands’ supply growth is expected to be in the form of the latter.123b Five major pipelines have been constructed in recent years to link the oil sands region to markets in the United States. A sixth pipeline, Keystone XL, is in the final stages of review by the U.S. State Department.123c If approved and constructed, Keystone XL would bring Canada’s total U.S. petroleum export capacity to over 4.1Mbpd, enough capacity to carry over a third of current U.S. petroleum imports.123d

This expansion of petroleum pipelines from Canada has generated considerable controversy in the United States. One specific area of concern has been perceived new risks to pipeline integrity of transporting heavy Canadian crudes. Some opponents of the new Canadian oil pipelines, notably the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), argue that these pipelines could be more likely to fail and cause environmental damage than other crude oil pipelines because the bitumen mixtures they would carry are “significantly more corrosive to pipeline systems than conventional crude,” among other reasons.123e They have called for a moratorium on approving new oil pipelines from oil sands regions, and a review of existing pipeline permits, until these safety concerns are researched further and addressed in federal environmental and safety studies. Canadian officials and other stakeholders have rejected these arguments, however, citing factual inaccuracies and a flawed methodology in the NRDC analysis, which compares pipeline spill rates in Canada to those in the United States.123f

Some in Congress have called for a review of PHMSA regulations to determine whether new regulations for Canadian heavy crudes are needed to account for any unique properties they may have. Accordingly, S. 275 would require PHMSA to review whether current regulations are sufficient to regulate pipelines transmitting “tar sands crude oil,” and analyze whether such oil presents an increased risk of release (§22). H.R. 2845 (§15) and H.R. 2937 (§21) would similarly mandate a review of PHMSA regulations to determine whether they are sufficient to regulate pipelines transporting diluted bitumen.

Pipeline Security Regulations

As noted earlier in this article, federal pipeline security activities to date have relied upon voluntary industry compliance with PHMSA security guidance and TSA security best practices.

By initiating this voluntary approach, PHMSA sought to speed adoption of security measures by industry and avoid the publication of sensitive security information (e.g., critical asset lists) that would normally be required in public rulemaking.124 Provisions in P.L. 109-468 require the DOT Inspector General to “address the adequacy of security standards for gas and oil pipelines” (§ 23(b)(4)). P.L. 110-53 similarly directs TSA to promulgate pipeline security regulations and carry out necessary inspection and enforcement—if the agency determines that regulations are appropriate (§ 1557(d)). Addressing this issue the 2008 IG report states that TSA’s current security guidance is not mandatory and remains unenforceable unless a regulation is issued to require industry compliance.... PHMSA and TSA will need to conduct covert tests of pipeline systems’ vulnerabilities to assess the current guidance as well as the operators’ compliance.125

Although TSA’s FY2005 budget justification stated that the agency would “issue regulations where appropriate to improve the security of the transportation modes,” the agency has not done so for pipelines, and is not currently working on such regulations.126 The pipelines industry has expressed concern that new security regulations and related requirements may be “redundant” and “may not be necessary to increase pipeline security.”127 The PHMSA Administrator in 2007 testified that enhancing security “does not necessarily mean that we must impose regulatory requirements.”128 TSA officials have questioned the IG assertions regarding pipeline security regulations, particularly the IG’s call for covert testing of pipeline operator security measures. They have argued that the agency is complying with the letter of P.L. 110-53 and that its pipeline operator security reviews are more than paper reviews.129 In accordance with P.L. 110-53 (§ 1557 (b)), the TSA has been implementing a multi-year program of pipeline system inspections, including documentation of findings and follow up reviews.130 In its oversight of potential pipeline security regulations, Congress may evaluate the effectiveness of the current voluntary pipeline security standards based on findings from the TSA’s CSR reviews, pipeline inspections, and future DOT Inspector General reports.

Additional Issues

In addition to the issues mentioned above, Congress may consider several issues related to proposed legislation or otherwise raised by pipeline stakeholders.

Accuracy and Completeness of Pipeline System Records

On January 3, 2011, as a response to its initial investigation of the San Bruno pipeline accident, the NTSB issued urgent new safety recommendations “to address record-keeping problems that could create conditions in which a pipeline is operated at a higher pressure than the pipe was built to withstand.”130a The NTSB issued these recommendations after it had concluded that there were significant errors in the records characterizing the San Bruno pipeline, and that “other pipeline operators may have discrepancies in their records that could potentially compromise the safe operation of pipelines throughout the United States.”130b PHMSA officials have also testified that some operators may not be collecting all the pipeline system data necessary to fully evaluate safety and compliance with federal regulations.130c In 2006, questions were raised about the accuracy of pipeline location data provided by operators and maintained by PHMSA in the National Pipeline Mapping System.130d At the time, agency officials reportedly acknowledged limitations in NPMS accuracy, but did not publicly discuss plans to address them. S. 234 (§17), S. 275 (§13), and H.R. 2937 (§13) would authorize PHMSA to collect additional pipeline data from operators to achieve the purposes of the NPMS. S. 1502 would require PHMSA to create a publicly available database of all pipeline water crossings in the United States (§4). Congress may consider whether these or other statutory measures would be sufficient to verify that pipeline operator information is complete and correct, particularly for older parts of the pipeline network.

Mandatory Internal Inspection or Hydrostatic Testing