Phthalates

This article was researched and written by a student at Mount Holyoke College participating in the Encyclopedia of Earth's (EoE) Student Science Communication Project. The project encourages students in undergraduate and graduate programs to write about timely scientific issues under close faculty guidance. All articles have been reviewed by internal EoE editors, and by independent experts on each topic.

Contents

Phthalates

Figure 1. Structural formula of DEHP. (Source: Wikipedia)

Figure 1. Structural formula of DEHP. (Source: Wikipedia) Phthalates are synthetic man-made chemical compounds used in industrial (polyvinyl chloride [PVC], carpet flooring, vinyl), household, personal care and medical products. People are exposed to phthalates in their daily lives without realizing it since there is no requirement for the chemicals to be listed in the ingredients list of such products as medical tubing or rubber duckies. Ten diverse classes of phthalates have been identified, and each class has varying usage and different toxicity profiles affecting the human body in both similar and in different ways.

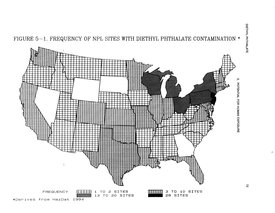

Phthalate molecules are ring-shaped and composed of esters (dialkyl) of 1,2-benzenedicarboxylic acid (Figure 1). Their physical properties are determined by the length and branching of the dialkyl side chains. Di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP) is one of the most widely used phthalates. Increasing numbers of studies are now becoming available on DEHP used in building products, food packaging, children’s products and medical devices. Trade names used for DEHP are Platinol DOP, Octoil, Silicol 150, Bisoplex 81 and Eviplast 80. It has been identified at 248 of the nation's 1,397 National Priorities List (NPL) hazardous waste site (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Frequency of NPL sites with DEHP contamination. (Source: CDC/ATSDR)

Figure 2. Frequency of NPL sites with DEHP contamination. (Source: CDC/ATSDR) Phthalates are used widely as plasticizers for polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastics. PVC products, for which environmental and health dangers are well documented, include household articles (for example, shower curtains, dishwashers, rain wear, car seats, and food wraps), medical devices (for example, medical tubing used for kidney dialysis, gloves and blood bags) and children's toys (for example, rubber duckies 3) and infant care products (for example, teethers and pacifiers). Also, PVC is used in the packaging material of such personal care items as baby oil, shampoo and lotion.

[3]. Soft rubber ducks like these may contain pthalates. (Source: Wikipedia)

[3]. Soft rubber ducks like these may contain pthalates. (Source: Wikipedia) Phthalates function to impart softness and flexibility to PVC polymers. Also, some respiratory care supplies are made either from or packaged in DEHP-softened vinyl bags and tubing. In fact, PVC plastics may contain up to 40% DEHP by weight. DEHP’s suitable properties contribute to the equipments’ flexibility, strength, ability to tolerate broad temperate change and resistance to bending. Phthalates are added to perfumes, deodorant, hair gels, mousses, hair sprays, and lotions to fix and make the fragrance last longer. Nail polish contains high concentrations of unlabeled Di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP) for preventing nail chipping and breaking. DBP, DnOP (Di-n-octyl-phthalate) and DEP are contained in insect repellents—at times triggering dermal and inhalation exposures.

|

Table 1. Use of phthalates. (Modified from: "Phthalates: toxicology and exposure", International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health[1]) | |

|

Class of phthalates |

Use |

|

Di-ethyl-phthalate (DEP) |

Personal care products, cosmetics |

|

Butyl benzyl phthalate (BBP) |

Vinyl tiles, food conveyor belts, artificial leather |

|

Di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP) |

PVC plastics, latex adhesives, cosmetics, personal care products, cellulose plastics, solvent for dyes |

|

Di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP) |

Building products (wallpaper, wire and cable insulation), car products (vinyl upholstery, car seats), clothing (footwear, raincoats), food packaging, children's products (soft toys, rubber duckies), medical devices |

|

Di-n-hexyl-phthalate (DnHP) |

Tool handles, dish-washer baskets, flooring, vinyl gloves, flea collars, conveyor belts used in food processing |

|

Di-n-octyl-phthalate (DnOP) |

Garden hoses, pool liners, flooring tiles, tarps |

|

Di-isononyl phthalate (DINP) |

Garden hoses, pool liners, flooring tiles, toys |

|

Di-isodecyl phthalate (DIDP) |

PVC plastics, PVC wires and cables, artificial leather, toys, pool liner |

DEHP in the environment

Usually DEHP adheres to dust particles in air or settles down on the ground due to gravity and rain. DEHP is broken down by microorganisms in water and soil to carbon dioxide and to other chemical products under the presence of oxygen. DEHP does not break down easily in deep soil or in rivers and lakes where there is little or no oxygen.

Human exposure to DEHP

Phthalate compounds are not bound to its main constituents in PVC polymers. They can be released, therefore, into air and water in the environment and into food materials through leaching from the plastic into the solid or water contents of plastic products. Heating or abrasion of the plastic contributes to increase leaching.

Phthalates enter the human body system through four exposure routes:

- oral (ingestion of DEHP-containing food including sucking children’s toys, or DEHP can leach into food material from plastics during processing and storing);

- dermal (absorption from contact with such DEHP-containing materials such as clothing, PVC gloves and personal care products);

- inhalation (DEHP-bound dust particles from building products and household furnishings); and

- intravenous (phthalates can leach from medical bags and tubes made from PVC (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Medical tubes used for intravenous therapy may contain phthalates. (Source: Wikipedia)

Figure 4. Medical tubes used for intravenous therapy may contain phthalates. (Source: Wikipedia) Studies have shown that DEHP concentrations may be higher in indoor air in newly furnished rooms—for example, rooms that have been freshly painted—than in outdoor air. High DEHP levels were found in German house dust samples, and the issue gained popular attention in light of the assumption that a child ingests 100mg dust per day.

The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) and the National Toxicology Program (NTP) began studying phthalates following a discovery that blood stored in PVC plastic bags for transfusion contained significant concentrations of phthalates. For an adult weighing 70kg and undergoing blood transfusion, exposure can be in doses of 3.5-4.3 mg/kg (parts per million). Special risk groups may include patients undergoing kidney dialysis who may have higher concentrations of DEHP in their blood, and ill children and pregnant women undergoing therapies or medical treatments using DEHP-containing medical devices. Also, workers may breathe higher than average levels of these compounds during manufacturing process in factories.

DEHP has been found in groundwater near landfills and industrial waste disposal sites where large amounts of plastics containing DEHP are buried. Higher than average levels of DEHP may be acquired from drinking water from wells located near such sites.

|

Table 2. An overview of the phthalates analyzed for their status and the highest measured concentration in perfumes is given. (Modified from: Scientific Committee on Consumer Products, 2007, Opinion on phthalates in cosmetic products). | |

|

Name |

Highest concentration in mg/kg (in perfumes) |

|

di-methyl phthalate (DMP) |

2,982 |

|

di-ethyl phthalate (DEP) |

22,299 |

|

di-isobutyl phthalate (DIBP) |

38 |

|

di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP) |

14 |

|

benzylbutyl phthalate (BBP) |

110 |

|

di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) |

167 |

|

di-n-octyl phthalate (DOP) |

Not found in study |

|

di-iso-nonyl phthalate (DINP) |

26 |

|

di-iso-decyl phthalate (DIDP) |

37 |

Some studies show that humans do not absorb phthalates as readily as rodents do. Two different metabolic processes occur in our body for lower and heavier molecule weight phthalates and the metabolic byproducts are eventually excreted through urine and feces. Low weight phthalates such as DEP undergo hydrolysis of one of their ester bonds and are converted to monoesters. The heavier phthalate molecules such as DEHP go through the same hydrolysis process of ester bonds, but this is followed by enzymatic oxidation resulting in a more hydrophilic molecule. In both cases resulting metabolites can then be excreted in urine and feces. Additionally, some secondary metabolites of DEHP undergo glucuronidation. This additional metabolism results in a more water soluble metabolite, and increased urinary excretion. Measurement of certain metabolites in body fluids such as urine or breast milk can and has been used as a biomarker of human exposure to pthalates.

Health effects of DEHP and metabolites in laboratory animals

Research in laboratory animals by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and others indicates that some phthalates behave as endocrine disruptors interfering with reproduction and development in both male and female rodents.

Rodents, primarily rats, exposed to DEHP have shown abnormalities in the nurse cell of the testes (sertoli cells) that facilitate sperm maturation. Also seen were a variety of male genital abnormalities including hypospadias (birth defect of the urethra in the male genitilia) and cryptorchidism (absence of one or both testes). Although these findings suggest that DEHP may function as an antiandrogen, there is no evidence that DEHP or any of its metabolites binds with the androgen receptor. It is possible however, that these effects may be the result of altered testosterone metabolism in the developing animal.

Other studies have demonstrated an association between DEHP exposure and skeletal, cardiovascular and eye abnormalities, neural tube defects and decreased anogenital distance in rodent pups. In female rats, DEHP and its metabolite disrupt normal biological processes by prolonging oestrous cycles, suppressing or delaying ovulation and reducing estrogen and progesterone concentrations. Also, di-iso-nonyl phthalate (DINP) demonstrated related patterns of reproductive toxicity although only at higher doses. The exact implication in humans is currently unclear.

DEHP in children

Studies have detected DEHP metabolites in breast milk—that upon ingestion can get directly into infants’ bodies. Exposure from indoor air is anticipated to be higher in infants and young children. Oral exposure in infants and children can occur through mouthing behaviors upon placing teethers into their mouths. Additionally, a recent study of infant urine (collected from diapers) demonstrated the correlation between the use of infant lotion, powder and shampoos with higher phthalate metabolite concentrations in urine samples of babies.

The transmission of DEHP and its metabolites via placenta to the fetus is known. Although it is uncertain, there is some chance that babies born to pregnant mothers may contain high levels of DEHP in their bodies. Phthalate exposure in pregnancy has been associated with changes in anogenital distance in newborn babies.

Reducing the use of phthalates to protect human health

Conscious efforts have been made by the European Union since 1999 in banning DINP from children’s soft plastic toys that are likely to be put in their mouths. The EU has banned the use of DEHP, DBP (di-n-butyl phthalate) and BBP (butylbenzyl phthalate) from any children’s toy products permanently. The German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment has proposed a stop to use of PVC materials containing DEHP where they can come in direct contact with food substances. In 1999, the Minneapolis-based Health Care Without Harm appealed the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for labeling of blood-storage bags and any DEHP-containing products.

In response to findings of DEHP’s toxicity and the threat it may pose to reproductive systems, U.S toy makers agreed to reduce DEHP use in soft vinyl toys to 3% in 1986. Instead of DEHP, many toy makers however began substituting DINP in those products. There has been removal of phthalate-containing teethers, rattles, and bottle nipples from some store shelves—but not completely. Only last October 2007, Arnold Schwarzenegger, the Governor of California, approved a ban on the use of three different phthalate congeners in products that children under three are likely to mouth. One of the top toys selling store—Toys “R” Us™—claimed it will comply with this ban by Jan 1, 2009.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) identifies DEHP as one of the most hazardous toxicants. The existence of such public interest organizations as Green Peace—and with such agencies as the EPA, NIEHS, NTP, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) battling for eliminating the use of various chemicals from consumer products as well as publishing reports on health hazards and disseminating information—promotes consumers to seek entitlement to safer products.

Notes (Phthalates)

References

- Agency for Toxic Substance and Disease Registry. 2002. Public Health Statement for Diethyl Phthalate.

- Babich, M.A. 1998. The risk of Chronic Toxicity Associated with Exposure to Diisononyl Phthalate (DINP) in Children’s Products. U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. December 1998.

- Barrett, J.R. 2005. Chemical Exposures: The Ugly Side of Beauty Products. Environmental Health Perspectives, January 2005.

- Becker, K., Seiwert, M., Angerer, J., Heger, W., Koch, H. M, Nagorka, R., Robkamp, E., Schluter, C., Seifert B., Ullrich, D. 2004. DEHP metabolites in urine of children and DEHP in house dust. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 207: 409-417.

- Chen, S.B., 1998. Migration of DINP from polyvinyl chloride children’s products. U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. p 2-20.

- Environmental Health Perspectives. 1999. Toxic Toys.

- Environment Science and Technology Online News. EU bans phthalates in children’s toys.

- Hauser, R., Calafat, A.M. 2005. Phthalates and Human Health. Occup. Environ. Med., 62, 806-818.

- Heudorf, U., Mersch-Sundermann, V., Angerer, J. 2007. Phthalates: Toxicology and Exposure. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 210: 623-634.

- Lovekamp-Swan, T., Davis, B.J. 2003. Mechanisms of Phthalate Ester Toxicity in the Female Reproductive System. Environmental Health Perspectives, 111: 139-144.

- Pickrell, John. 2002. More than Skin Deep? Beauty products may damage fetal development. Science News Online, 20 July 2002.

- Raloff, Janet. 2000. New concerns about Phthalates. Science News Online, 2 September 2000.

- Sathyanarayana, S., Karr, C.J., Lozano, P., Brown, E., Calafat, A.M., Liu, F., Swan, S.H. 2008. Baby Care Products: Possible Sources of Infant Phthalate Exposure. American Academy of Pediatrics, 121: 260-268.

- SCCP (Scientific Committee on Consumer Products). 2007. Opinion on phthalates in cosmetic products, p 1-19.

- Schettler, Ted. 2005. Human exposure to phthalates via consumer products. International Journal of Andrology, 29: 134-139.

- Schwartz, D.A , Korach, K.S. 2007. Emerging Research on Endocrine Disrupters. Environmental Health Perspectives, 115 (1): p A-13.

- Shea, K.M. and Committee on Environmental Health. 2003. Pediatric Exposure and Potential Toxicity of Phthalate Plasticizers. American Academy of Pediatrics, 111: 1467-1474.

- Stringer, R., Johnston, P., Erry, B. 2001. Toxic Chemicals in a Child's World: An investigation into PVC. Greenpeace Report.

- Underwood, Anne. The Chemicals Within. Newsweek, 4 February 2008.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. EPA Technology Transfer Network Air Toxics Web Site - Bis(2-ethylhexyl)pthalate (DEHP).