Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary

Contents

- 1 Introduction Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary is administered by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and was designated in 1994 as the first National Marine Sanctuary in the Pacific Northwest. It encompasses 3,310 square miles off of Washington State's Olympic Peninsula, extending 135 miles along the Washington Coast from about Cape Flattery to the mouth of the Copalis River. The seaward boundary of the Sanctuary varies from about 25 to 40 miles offshore. This includes most of the continental shelf, as well as parts of three important submarine canyons, the Nitinat Canyon, the Quinault Canyon and the Juan de Fuca Canyon. It shares 65 miles of coastline with Olympic National Park, including some of the last remaining wilderness coastline in the lower 48 states. Olympic National Park and the Sanctuary share resource management jurisdiction in the intertidal zone (Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary)

- 2 History

- 3 Ocean Processes

- 4 Coastal Geology

- 5 Habitats

- 6 Further Reading

History

What is now Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary has a long tradition of exploration. The northwest tip of the Olympic Peninsula has had an almost magnetic attraction for sailors and cartographers for almost 400 years. Juan de Fuca was the name of a Greek ships' pilot who reported visiting what is now known as the the Strait of Juan de Fuca in the 1590s. It was here, according to the itinerant Greek ship pilot named Juan de Fuca, that the Northwest Passage emptied into the Pacific Ocean. Juan de Fuca, also known as Apostolos Valarianos, claimed that he found a passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans in 1592. His visit was never confirmed although his name was preserved on later English maps.

For 200 years after his account was published in 1596, Spain, England, France and Russia all sent explorers to confirm his report and lay claim to the region and its riches. The earliest European explorations of the Pacific coast were conducted by the 16th century Spanish. These voyages were cloaked in secrecy. Documented Spanish exploration on the Northwest Coast began in earnest in the mid-1770s. The first known landing on the Washington coast was attributed to Bruno Heceta in 1775 at the mouth of the Hoh River. His crew were turned back by Indians and he returned to the south having missed the entrance to the strait.

During the next twenty years several European expeditions explored and mapped the Northwest Coast. Captain James Cook was already a noted Pacific explorer when he passed Cape Flattery on his way to Nootka in March 1787. It was on this voyage that Cook named Cape Flattery because it deceived (or "flattered") him into believing he might find Juan de Fuca's fabled strait to the east.

The otter pelts the English obtained from the Indians were to be the key to opening the coast to European colonial ambitions. Cook's sailors sold the furs at great profit when they stopped in China after their Northwest Coast visit. Home in England, the sailors spread stories about the fantastic prices to be had for Northwest pelts in China. Following the publication of Cook's reports in 1784, British ships began to travel to the Pacific Northwest to hunt the sea otters.

Thanks to John Ledyard, one of Cook's Americanized crewmen, American traders began to learn about the potential wealth. New England ship owners, too, began to exploit the region's otters for their luxuriant fur.

Sea otters were hunted to extinction in Washington in the early 1900s. Otters from Alaska were reintroduced in 1969 and 1970 and gradually have made a comeback. The current sea otter population numbers over 500 and otters have been seen in the Strait of Juan de Fuca and along the west coast of Vancouver Island.

As the British and Americans competed for economic supremacy in the Northwest fur trade, the Spanish were slowly eclipsed. Political events in Continental Europe combined to distract Spanish and English attention while the Americans seized the economic advantage. Spain's three-hundred year old New World empire had weakened while France's attempts at European empire building left the Pacific open to New England's seafaring Yankee traders. In an attempt to curb their competitors' incursions into the region, the Spanish had attempted to establish outposts at strategic places. Their primary port was at Nootka Bay on Vancouver Island. They established several outposts about the region including on at Neah Bay to serve as a base for surveying the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the San Juan Islands and the Georgia Strait. Although the bay commanded the entrance to the Strait and provided access to the sea, its shallow rocky bottom and exposure to northwest winds were disadvantages. The pallisaded settlement and port of Nuñez Gaona was briefly established at Neah Bay in spring 1792 under command of Salvador Fidalgo.

Because of tensions with the Makah and an unsettled political relationship with the British, Neah Bay was abandoned in the fall of 1792, leaving behind only the crude bricks of a primitive bread oven. The last established Spanish foothold on the Northwest Coast was also the first to fall.

Two hundred years later, our explorations are very different. Instead of exploring to conquer, we are exploring to learn how to protect the marine environment. Although this place has been on the map for several centuries, we do not know much of what is below the surface other than rough contours of the bottom. Exploration involves discovery and it involves mystery. But it also involves something more important—not just what flag flies over this part of the world, but what biological riches of the marine environment will be passed on to future generations.

Cultural History

The Olympic Coast has sustained human communities for at least 6,000 years and possibly much longer. Prehistoric archaeology sites have revealed human occupation along much of the shoreline. One site—Ozette Village—has given us a dramatic glimpse of Makah culture which centered around whaling and other ocean-dependent hunting, gathering and fishing activities. Today's Makah, Quileute, Hoh and Quinault tribes carry their heritage forward balancing their roles as natural resource managers and stewards of traditional culture. Browse here to learn more about Native Cultures and Contemporary Tribes of the Olympic Coast.

Since the dawn of the Age of European Exploration, the Olympic Coast has occupied a special place on the map. As early as the 17th Century, the rumor of a Northwest Passage was associated with this area. European "discovery" of the Strait of Juan de Fuca in the 1790s brought a rush of explorer/traders and sparked intense competition among Spain, Russia, England and the fledgling United States. Over 180 shipwrecks mark the history of maritime shipping on the Olympic Coast, their remains broken by the intense natural forces of the coastline or concealed from us in deeper parts of the Sanctuary.

Throughout the period of settlement of the western Olympic Peninsula, the link between the land and the ocean has shaped history. Early canneries, logging operations and hotels reflected not just the economic opportunities brought about by coastal resources, but the hardships imposed by the Olympic Coast's remoteness.

Maritime History

The combination of fierce weather, isolated and rocky shores, and heavy ship commerce established, early on, the Olympic Coast as a graveyard for ships. More than 150 wrecks have been historically documented in the vicinity of the Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary, an amount proportional to the commercial development in the region and the region's significance in the economic lives of the United States and Canada.

There are few recorded shipwrecks prior to the mid-nineteenth century, and no authentically-reported wrecks during the eighteenth century. The number of losses increased significantly as Puget Sound developed as an economic center and as Victoria developed on the north side of the Strait in the later 19th century.

Ship losses were predominantly weather-related, including founderings, collisions and groundings. Many ships simply disappeared, their last known location recorded by the lighthouse tender at Tatoosh before they disappeared into watery oblivion. "Last sighted, Cape Flattery," is the grim epitaph for many unfortunate ships and crew.

One of the best-known wrecks on the Olympic Coast was that of the Austria, a Bath, Maine-built "downeaster" converted from a fullrigged ship to a bark to ply the West Coast trade. Fragments of the Austria remain visible at Cape Alava during extreme low tides.

Ocean Processes

One of the most important ocean processes on the Olympic Coast is upwelling. Seasonal weather patterns create summer winds from the north that push coastal surface water offshore. This in turn draws deeper, nutrient-rich water upward and into the sunlight zone. This triggers explosive growth of plankton and organisms all the way up thefood chain.

Large seasonal currents are important for the distribution of fish as well as the movement of sediment along the shore. Smaller-scale currents are important for distributing fish and invertebrate larvae, carrying them from rich breeding areas and spreading them over a wide range of suitable habitats.

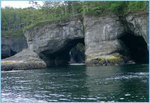

The raw power of the ocean is apparent almost everywhere along the Olympic Coast. Winter storms that arrive from the southwest create waves that have chiseled the shore into rugged cliffs, headlands, offshore islands and seastacks.

Coastal Geology

The Pacific rim of the United States is the geologically active edge of the North American continental plate. It is and has been in a constant state of colliding and overriding the sea floor of the Juan de Fuca oceanic crustal plate. The Sanctuary is subject to tectonic forces caused by the combined movements of the large Pacific and North America Plates and the smaller Juan de Fuca Plate. The altered sedimentary rocks of the Olympic Mountains and the volcanoes of the Cascade Range (Mount Saint Helens, for example) are the result of the convergence of these plates composed of oceanic and continental crusts.

The coastal rim of the continental plate is marked by earthquakes associated with geological faulting and volcanism. A continental shelf reaches out from Washington's coast from eight to forty miles (Washington State Dept. of Ecology, 1986). This shelf provides a relatively shallow coastal environment within the Sanctuary. Submarine canyons cut into the continental shelf and slope along the entire coastline of the sanctuary.

In the northern portion of the Sanctuary, the underwater continental shelf slope is steep and jagged. The underlying sediments are largely glacial deposits. Modern sediments are brought in along the Strait of Juan de Fuca. The Columbia River is the dominant source of modern sediments for the southern Washington Shelf (Nittrouer, 1978 in Baker and Hickey, 1986). Year-round bottom currents and winter storms transport much of this sediment north to northwest. The sediment accumulates on the shelf as a band of sandy silt with the inner shelf sandy and the outer shelf comprised primarily of silt and clay (Carson, et al., 1986). Much of this sediment is transported to and deposited in the Quinault Canyon where it gradually works downhill into the Cascadia Basin.

Overlying the bedrock along many areas of the coast are deposits of sand and gravel laid down by glacial streams during extensive glaciation of the Olympic Mountains during the Pleistocene Epoch some 17,000 to 70,000 years ago. Prominent gravel pockets lie off Cape Flattery, Grays Harbor, and the mouth of the Quinault River.

The uplifted broad coastal plain that forms the coast of Washington extends from Cape Flattery southward and includes two tidal inlets, Willapa Bay and Grays Harbor (Weissenborn and Snavely, 1968). Broad beaches, dunes, and ridges dominate the coastline from Cape Disappointment on the north side of the Columbia River mouth, to the Hoh River (Moore and Luken, 1979). The plain rises eastward and merges with the foothills of the Olympic Mountains. Wave action has eroded the plain through time and formed steep cliffs along the coast, except at river mouths.

For most of the coast between Cape Flattery and Point Grenville these cliffs rise abruptly 50 to 300 feet above a wave-cut platform. This wave-cut platform, which normally extends about half a mile from shore, is nearly two miles wide west of Ozette Lake. Small islands, sea stacks, and rocks dot the platform's surface.

Islands can be found in all stages of development from partially isolated promontories to true islands several acres in extent. The largest, Destruction Island, is 1.5 km long.

Habitats

Habitats are building blocks in the living ecosystem. A habitat is like an organism's home address—the place where it finds food, water, shelter, and space—everything it needs in order to survive. Marine habitats, like those on land, form the key to healthy communities of marine wildlife. The Olympic Coast contains many different habitats—some we see from land and others hidden beneath the water.

At the water's edge is the intertidal zone, a habitat that alternates between the dry and wet worlds. Tide pools occur where boulders and rocky outcrops trap seawater when the tide recedes. At high tide, they form surge channels, crevices and cracks that are home to many familiar seashore animals, like seastars, hermit crabs and sea anemones.

Because they contain so many interesting life forms, tide pools are often damaged by careless trampling and collecting. Enjoying tidepool life calls for special tide pool etiquette in order to experience and enjoy these special habitats without damaging them.

The kelp forest is another important habitat visible from the water's edge. Gently swaying blades of bull kelp and giant kelp form the Olympic Coast's most important kelp habitats. Kelp beds form dense stands resembling old growth forests of the land, in which many species of fish and invertebrates thrive. Sea otters are most often seen rafting and resting in and near kelp forests.

Other habitats are found underwater. Reefs and rock outcrops form important structures that attract many types of fish. The ocean floor, from the sunlit shallows to the perpetually dark depths, support many types of fishes and invertebrates.

In the midwater realm, vast clouds of plankton bloom, attracting schools of fish and their predators. Jellies and other lifeforms drift, wiggle, rotate and dart as they hang in the currents. And far offshore, the pelagic ocean sustains wandering flocks of pelagic seabirds, and migrating whales.

Further Reading

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the National Marine Sanctuary. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the National Marine Sanctuary should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |