Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve (Coral reefs (collection))

Contents

- 1 Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve

- 1.1 Introduction The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (NWHI) Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve is the single largest conservation area under the U.S. flag, and the largest marine conservation area in the world. It encompasses 137,792 square miles of the Pacific Ocean - an area larger than all the country's national parks combined. Map of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. The extensive coral reefs found in the NWHI - truly the rainforests of the sea - are home to over 7,000 marine species, one quarter of which are found only in the Hawaiian Archipelago. Many of the islands and shallow water environments are important habitats for rare species such as the threatened green sea turtle and the endangered Hawaiian monk seal. The NWHI are also of great cultural importance to Native Hawaiians with significant cultural sites found on the islands of Nihoa and Mokumanamana. The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Marine National Monument was created by Presidential proclamation on June 15, 2006. (Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve)

- 1.2 Cultural History

- 1.3 Maritime Heritage

- 1.4 Research and Monitoring

- 1.5 Flora and Fauna

- 1.6 Further Reading

Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve

Introduction The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (NWHI) Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve is the single largest conservation area under the U.S. flag, and the largest marine conservation area in the world. It encompasses 137,792 square miles of the Pacific Ocean - an area larger than all the country's national parks combined. Map of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. The extensive coral reefs found in the NWHI - truly the rainforests of the sea - are home to over 7,000 marine species, one quarter of which are found only in the Hawaiian Archipelago. Many of the islands and shallow water environments are important habitats for rare species such as the threatened green sea turtle and the endangered Hawaiian monk seal. The NWHI are also of great cultural importance to Native Hawaiians with significant cultural sites found on the islands of Nihoa and Mokumanamana. The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Marine National Monument was created by Presidential proclamation on June 15, 2006. (Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve)

Cultural History

Early Settlers

The Pacific Ocean covers one-third of the surface of the Earth and is comprised of thousands of islands that are scattered over a vast expanse of water with shifting winds, and strong currents. The movement of ancestral Oceanic people, or kanaka maoli, across remote Oceania was one of the most remarkable feats of open-ocean voyaging and settlement in all of human history. In the Hawaiian archipelago, the northwestern region were the most peripheral islands that relied heavily on interaction and networking between core islands (the main Hawaiian Islands) as a social mechanism to help reduce the possibility of extinction of their geographically isolated populations.

The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands were explored, colonized, and in some cases permanently settled by Native Hawaiians in pre-contact times. Nihoa and Mokumanamana, the islands that are closest to the Main Hawaiian Islands, have archaeological sites including agricultural, religious, and habitation features. Based on radiocarbon dating, it has been estimated that Nihoa and Mokumanamana could have been inhabited from 1000 A.D. to 1700 A. D. These islands pose the same dilemma as a score of other islands in Oceania, which were small targets for voyaging and often at some distance from their nearest occupied neighbor. All of these islands were either empty at contact or abandoned, having been occupied some time previously. Due to the environmental constraints of being small, geographically isolated, and not having enough resources to allow self-sustainability, demographic stability (in initial and later stages of colonization) has been thought to be the main reason why interaction was so vital to these regions.

Cultural Research and Significance

The first discoverers of the Hawaiian Archipelago, Native Hawaiians have continued to inhabit these islands for thousands of years prior to Western contact. During this time, Native Hawaiians developed complex resource management systems and a specialized set of skills to survive on these remote islands with limited resources. Native Hawaiians continue to maintain their strong cultural ties to the land and sea and continue to understand the importance of managing the islands and waters as inextricably connected to one another.

More specifically, the ocean played an important role to Native Hawaiians as it was used for resources and physical and spiritual sustenance in their everyday lives. Poetically referred to as ke kai popolohua mea a Kane (the deep dark ocean of Kane), the ocean was divided into numerous smaller divisions and categories beginning from the nearshore to the deeper pelagic waters. Likewise, channels between islands were also given names and served as connections between islands, as well as a reminder to their larger oceanic history and identity.

In Hawaiian traditions, the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (NWHI) are considered a sacred place, a region of primordial darkness from which life springs and spirits return after death (Kikiloi 2006). Much of the information about the NWHI has been passed down in oral and written histories, genealogies, songs, dance, and archaeological resources. Through these sources, Native Hawaiians are able to recount the travels of seafaring ancestors between the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands and the main Hawaiian Islands. Hawaiian language archival resources have played an important role in providing this documentation, through a large body of information published over a hundred years ago in local newspapers (e.g., Kaunamano 1862 in Hoku o ka Pakipika; Manu 1899 in Ka Loea Kalai‘aina; Wise 1924 in Nupepa Kuoko‘a). More recent ethnological studies (Maly 2003) highlight the continuity of Native Hawaiian traditional practices and histories in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Only a fraction of these have been recorded, and many more exist in the memories and life histories of kupuna.

Historical Period

By the time of Western European contact with the Hawaiian Islands, little was collectively known by the majority of the population about the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands as few had traveled to these remote islands and seen them with their own eyes. Within the next century, a number of expeditions were initiated by Hawaiian ali‘i to visit these islands and bring them under Hawaiian political control and ownership. The accounts of these historical expeditions were published in great detail in the newspapers from 1857 through 1894, as they related to each visit.

The sovereignty, life (ea), and responsibility (kuleana) for the entire Hawaiian Archipelago continues to exist in the hearts and minds of many Native Hawaiians. This position was recognized by the “Apology Bill” (U.S. Public Law 103-150), a joint resolution of Congress signed by the President in 1993. The Apology Bill acknowledges the wrongful role of United States’ officers in the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawai‘i and “apologizes to Native Hawaiians on behalf of the people of the United States” for the unlawful overthrow and the “deprivation of the rights of Native Hawaiians to self-determination.” It also recognizes that “the health and well-being of the Native Hawaiian people is intrinsically tied to their deep feelings and attachment to the land.”

Cultural Access for Native Hawaiian Practices

The Executive Order that established the Reserve states that “culturally significant, non-commercial subsistence, cultural, and religious uses by Native Hawaiian should be allowed within the Reserve, consistent with applicable law and long-term conservation and protection of Reserve resources.” Sanctuary goals and objectives reinforce this position, and go further with Objective 5B to “develop a plan for Native Hawaiian access and use in the NWHI, collaboratively with Native Hawaiians and regional partners.”

While subsistence, and more broadly Native Hawaiian practices, are recognized and protected in the Hawaiian Islands (Constitution of the State of Hawaii), definitions differ in various marine managed areas (Constitution of the State of Hawaii). The Sanctuary definition of Native Hawaiian practices and subsistence use is based on a review of existing definitions, the goal and objectives of the Sanctuary, and the July 2004 Reserve Advisory Council recommendation.

Native Hawaiian Practices means cultural activities conducted for the purposes of perpetuating traditional knowledge, caring for and protecting the environment, and strengthening cultural and spiritual connections to the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands that have demonstrable benefits to the Native Hawaiian community. This may include, but is not limited to, the non-commercial use of Sanctuary resources for direct personal consumption while in the Sanctuary.

Contemporary connections

Today, Native Hawaiians remain deeply connected to the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands on genealogical, cultural, and spiritual levels. Kaua‘i and Ni‘ihau families voyaged to these islands indicating that they played a role in a larger network for subsistence practices into the 20th century. In recent years, Native Hawaiian cultural practitioners voyaged to the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands to honor their ancestors and perpetuate traditional practices. In 1997, Hui Malama i Na Kupuna o Hawai‘i Nei repatriated sets of human remains to Nihoa and Mokumanana that were collected by archaeologists in the 1924-25 Bishop Museum Tanager Expeditions (Ayau and Tengan 2002). In 2003, a cultural protocol group, Na Kup‘eu Paemoku, traveled to Nihoa on the voyaging canoe Hokule‘a to conduct traditional ceremonies. In 2004, Hokule‘a sailed over 1,200 miles to the most distant end of the island chain to visit Kure Atoll as part of a statewide educational initiative called “Navigating Change.” In 2005, Na Kupu‘eu Paemoku sailed to Mokumanamana to conduct protocol ceremonies on the longest day of the year, June 21—the Summer Solstice.

Archaeology

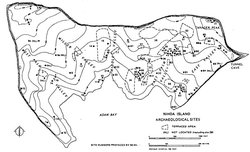

Nihoa and Mokumanamana Islands are recognized as culturally and historically significant and are listed on the National and State Register for Historic Places and protected by the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service in accordance with the National Wildlife Refuge System Administration Act of 1966, as amended. Archaeological surveys on Nihoa and Mokumanamana have documented numerous cultural sites and material (Emory 1928; Cleghorn 1988; Graves and Kikiloi, in prep.). Nihoa Island, where there is significant soil development, has over 88 cultural sites, including ceremonial, residential, and agricultural features. Mokumanamana Island has 52 cultural sites, including ceremonial and temporary habitation features. Several archaeological surveys have collected cultural artifacts from both these islands, which are now curated at the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum and University of Hawai‘i at M?noa Archaeological Laboratory. The range in types of cultural artifacts stored in these collections is testimony to the various uses these islands and surrounding waters served for Native Hawaiians.

Maritime Heritage

The unique islands and atolls of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (NWHI), due to their isolation, are reserves for ecosystem diversity, and the intelligent management of their natural resources is of critical concern. The NWHI also possess a rich maritime history and special non-renewable resources—for example, submerged maritime heritage resources, such as shipwrecks, sunken aircraft, and other archaeological sites. Such historic sites are like windows into the past. There may be as many as 60 vessels known lost among the atolls and at least 67 naval aircraft sunk in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, but who knows how many more have yet to be discovered.

Shipwrecks in the NWHI have been a well-known phenonmenon for many years. In 1915 the Reverend J.M. Lydgate, in his opening remarks to “Wrecks to the North-west,” summarized the hazardous nature of the atoll environment:

The islands and reefs to the northwest of Hawaii have been a veritable graveyard of marine disaster. The two sufficient reasons for this have been, first, the low, inconspicuous character of the islands, and, second, the faulty or insufficient location of them on the marine charts. The menace of the iceberg is the fact that it lies seven-eighths underwater and you strike some submerged, protruding spur of it before you dream of danger. In a much more disastrous way the same thing is true of many of these islands. --Reverend J.M. Lydgate, 1915

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA’s) National Marine Sanctuary Program seeks to increase the public awareness of America’s maritime heritage by conducting scientific research, monitoring, exploration and educational programs. This heritage component is supported by the National Marine Sanctuaries Act (16 USC 1431) which states: “…a federal program which establishes areas of the marine environment which have special conservation, recreational, ecological, historical, cultural, archeological, scientific, educational, or esthetic qualities as national marine sanctuaries managed as the National Marine Sanctuary System.”

Today, 13 national marine sanctuaries encompass more than 18,000 square miles of America’s ocean and Great Lakes natural and cultural resources. NOAA’s Maritime Heritage Program, created in 2002, is an initiative of the National Marine Sanctuaries Program (NMSP). The program focuses on maritime heritage resources within the thirteen designated National Marine Sanctuaries, and also promotes maritime heritage appreciation throughout the entire nation.

Maritime heritage is a broad legacy that includes not only physical resources, such as historic shipwrecks and prehistoric archaeological sites, but also archival documents, oral histories, and traditional seafaring and ecological knowledge of indigenous cultures. The vision of the Maritime Heritage Program is that a broad spectrum of Americans will be engaged in the stewardship and appreciation of our national maritime heritage.

As with natural resources, numerous user and interest groups, from archaeologists to recreational divers, seek to interact with maritime heritage resources in many different ways (exploration, photography, excavation, etc.). These resources also are impacted by natural factors such as storms, currents and corrosion. Therefore, responsible, informed decisions must be made on how to manage these resources for the enjoyment and appreciation of current and future generations. Maritime heritage resources, unlike living resources, are nonrenewable, so it is especially important that we protect these important links to our past.

Maritime heritage resources, when properly studied and interpreted, add an important dimension to our understanding and appreciation of our nation’s rich maritime legacy, and make us more aware of the critical need for us to be wise stewards of our ocean planet.

Research and Monitoring

Scientific, cultural, and maritime research are important parts of the overall operations of the Monument. The Monument's coral reef research program focuses on basic habitat characterization. Reef surveys have recorded the diversity and abundance of fishes, algae, corals, and other reef invertebrates at numerous locations throughout the archipelago. Historical and cultural resources such as shipwrecks have also been documented on shallow reefs by Monument and National Marine Sanctuary Pacific Region archaeologists. Research in deeper offshore waters has utilized multibeam sonar and submersibles to document rarely seen biological resources and topographical features contained within Monument waters. The results of these shallow and deep-water research efforts will aid in the creation of management plans for the largest coral reef system in the United States.

Flora and Fauna

Marine Mammals

The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands attract many diverse species of whales, dolphins, and seals. These mammals spend most of, if not their entire lives, in the water. Their front limbs have evolved into paddle shaped flippers and their tails are flattened laterally. Whales and dolphins have stream-lined bodies and an external blowhole on the top of the head. They can be found living alone or in large aggregations, and can dive for extended periods of time, sometimes to great depths. There are a number of whales and dolphins within reserve waters, including humpback, sperm, false killer and melon-headed whales, as well as spinner, rough-toothed and Risso’s dolphins. Hawaiian waters and beaches are also home to the endangered Hawaiian monk seal, a solitary species that can be found feeding around coral reefs, or resting on beaches.

Fish

This diverse group includes bony fish, sharks, and rays that live within a variety of habitats including seagrass beds, coral or rocky reefs, sandy bottoms and the open ocean. Hawaiian waters are home to hundreds of unique and endemic coral reef fish species, one quarter which are found nowhere else in the world. The reefs, atolls, and deep-water banks and seamounts provide critical habitat for many ecologically and commercially important fish species, which play an important role in the ecosystem and the economy.

Marine Birds

Seabirds do not comprise a taxonomic or evolutionary group of birds; they are simply defined as birds that spend most of their life feeding and living on the open ocean, coming to land only to breed. The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands have productive, food-rich waters that make it a major foraging area for thousands of seabirds such as albatross, terns, boobies, shearwaters, petrels, tropicbirds, and other offshore species. The numerous islands and small atolls in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands create important nesting habitat for the many migratory and resident species. For some bird species, such as the Laysan Albatross, the region supports the largest colony in the world, and is found on Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge, managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Invertebrates

Marine invertebrates are the most diverse and abundant group of organisms in the ocean. This grouping is not based on a single taxon, but is defined as a group of animals found in the marine environment which lack a vertebral column. There are hundreds of species of invertebrates in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, such as corals, urchins, lobsters, crabs, snails, octopus, jellies, and sea stars. The coral reefs themselves are built by extremely large numbers of colonial invertebrate polyps which collectively provide habitat for countless other invertebrate species. The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands support about 70% of all coral reef habitat in U.S. waters.

Plants and Algae

Both plants and algae are primary producers, deriving energy from the sun through photosynthesis to form the base of the food web in the ocean. There are over 150 species of alga that live among the Northwestern Hawaiian Island reefs, including red, green, and brown algae as well as some seagrasses. These undersea plants and algae produce oxygen during photosynthesis, provide habitat for marine animals, and are a food source for numerous species. Some species produce calcified structures that actually aid in reef building. There are even several newly-discovered endemic algae species in the waters of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

Marine Reptiles

Reptiles are relatively uncommon residents of the marine environment. Of the small group of reptiles that inhabit the sea, perhaps the most easily recognized are the sea turtles. There are only seven species of sea turtles worldwide, and all but one are endangered. Sea turtles, such as the loggerhead, hawksbill, green, and olive ridley, are found in the waters of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve. Over 90% of the threatened Hawaiian population of green sea turtles travel through reserve waters to nest on the sandy islets of the Hawaiian Islands National Wildlife Refuge at French Frigate Shoals.

Further Reading

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the National Marine Sanctuary. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the National Marine Sanctuary should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |