Northern minke whale

The Northern minke whale (scientific name: Balaenoptera acutorostrata), is a very large marine mammal, in the family of Rorquals (Balaenoptera), part of the order of cetaceans. The Minke is a baleen whale, meaning that instead of teeth, it has long plates which hang in a row (like the teeth of a comb) from its upper jaws. Baleen plates are strong and flexible; they are made of a protein similar to human fingernails. Baleen plates are broad at the base (gumline) and taper into a fringe which forms a curtain or mat inside the whale's mouth. Baleen whales strain huge volumes of ocean water through their baleen plates to capture food: tons of krill, other zooplankton, crustaceans, and small fish.

The smallest of the rorqual whales (and the second-smallest baleen whale), the minke whale is also the most abundant. Two species are now recognised, the northern hemisphere minke whale (the subject of this species page) and the southern hemisphere Antarctic minke whale (Balaenoptera bonaerensis). Minke whales are slim in shape, with a pointed dolphin-like head, bearing a double blow-hole. The smooth skin is dark grey above, while the belly and undersides of the flippers are white, and there is often a white band on the flipper. When seen at close quarters, minke whales have variable smoky patterns which have been used to photo-identify individuals.

Minke whales feed on fish and various invertebrates; like all baleen whales they filter their food from the water using their baleen plates like sieves. Although largely a solitary species, when feeding minke whales can often be seen in pairs, and on particularly good feeding grounds up to a hundred individuals may congregate. A number of feeding techniques have been observed, including trapping shoals of fish against the surface of the water. After a ten month gestation period, births occur in mid-winter, at birth the calf measures up to 2.8 metres in length. It will be weaned at four months of age, and will stay with its mother for up to two years, becoming sexually mature at seven years of age. Minke whales have an average life span of around 50 years. Minke whales are fairly inquisitive and often swim by the side of boats for up to half an hour.

Contents

Physical Description

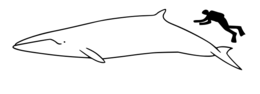

There is a clear sexual dimorphism for the species, with females being larger than males. The species length for an adult range from 6.7 to 9.8 metres (m) in males, but reaching 7.3 to 10.7 m females. Body mass is generally in the range of 20,000 to 40,000 kilograms. Distinguishing characteristics are: white flipper patches; blow not readily visible. colour being light grey with white belly.

The Minke is a medium sized whale, sleek in shape, with a very pointed head. It is dark grey to black in colour with a white underside and has white patches behind the head and a bright white band on the outer part of the flippers. The newborn calf is approximately 2.5 m long and weighs about 350 kg. There are 30 to 70 throat grooves that always end before the navel (umbilicus). The dorsal fin is sickle-shaped, and about two-thirds of the way back from the tip of the animal's snout. The tail flukes are a quarter of the animal's length in width, and are not shown when diving. There are 230 to 360 baleen plates, 12 to 20 cm long, in each half of the upper jaw, which are yellowish-white at the front to grey-brown at the rear.The blow is very weak and can been seen at the same time as the dorsal fin appears. Spyhopping and breaching are common for this species, which forms small groups of up to three individuals. The Minke can remain submerged for up to 20 minutes (Kinze, 2002).

This whale could be confused at a distance with the Sei whale and the Bryde's whale as they are relatively the same size, however the weak blow of the Minke whale and dorsal fin appearing at the same time as the blow is characteristic. At close range the white bands on the minke's flippers are diagnostic (Jefferson et al., 1993; Kinze, 2002).

Behavior

Minke whales travel either singly or in small groups (2-4), although they can be found in large aggregations in the hundreds where krill is abundant. They are thought to be curious, approaching ships and wharfs which is not typical of its family. They are also highly acrobatic, able to leap completely out of the water like a dolphin. Minkes are fast swimmers. Some populations are migratory--both southern and northern populations often spend winter in tropical waters, although these are actually at different times of year as a result of seasonal differences in their homelands.

Sounds

Balaenoptera acutorostrata produces an extensive range of soundvocalizations. Mellinger and Carson (2000) analyzed pulse trains of minke whales in the Caribbean Sea and classified them into two categories: the “speed-up” trains and the less common “slow-down” trains. Pulse trains are sequences of pulses produced at both regular or irregular intervals. There is limited information, however, as to whether this type of vocalization is also present in B. bonaerensis and what function it serves in B. acutorostrata. (Mellinger and Carson, 2000)

Reproduction

Only one calf is born at a time. Gestation lasts for 10 to 11 months. Body mass at birth is 450 kg. The young are weaned at around five months, but they do not become sexually mature until age six. Females are thought to have young every other year. The breeding period is long: from December to May in the Atlantic and year-round in the Pacific. Peak months for births are December and June. Growth ceases at about 18 years for females and 20 years for males.

Lifespan/Longevity

These animals have been estimated to live up to 50 years in the wild (Bernhard Grzimek 1990).

Distribution and Movements

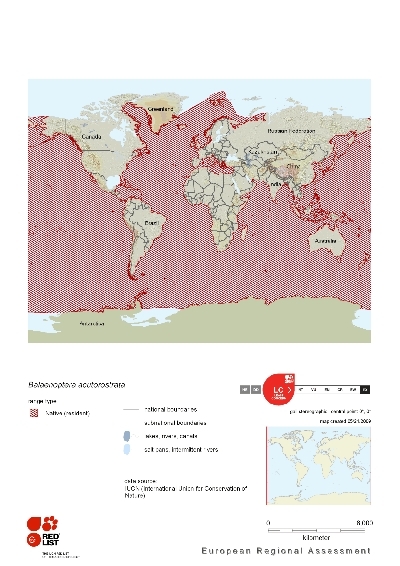

Minke whales have a worldwide distribution, appearing in all oceans and some adjoining seas. Note that only the Antarctic minke whale is found in the Southern Ocean. Cooler regions seem to be preferred over tropical regions.

Although not considered coastal, these baleen whales rarely venture farther than 169 km from land. They also commonly enter estuaries, bays, fjords, and lagoons. They are also know to move farther into polar ice fields than other rorqual species.

This whale is usually more concentrated in higher latitudes during the summer and lower latitudes during the winter, but migrations vary from year to year.

Food and Feeding Habits

A baleen whale, this species feeds primarily on krill and some small fish. There are regional differences in the diet. Minkes eat krill almost exclusively in the Antarctic, but they are more omnivorous in the northern hemisphere, taking as food squid and small vertebrates such as cod, herring, and sardines.

Threats and Conservation Status

The common name of this species indicates the main threat that has faced it for many years; Minke was an 18th Century Norwegian whaler who hunted small whales, flouting the whaling rules of the day. Minke whales have been hunted by people for products such as meat, oil, and baleen since the Middle Ages. Regardless, it has never been of large commercial importance until other whale species were overhunted.

Annual kill peaked in 1976 with 12,398 individuals, but now is down to less than 1000. These are taken primarily by indigenous peoples for food, or by scientists for research. Despite the world moratorium on commercial whaling set up by the International Whaling Commission (IWC) in 1982, minke whales are still hunted by Norway and Japan. Norway officially objected to the moratorium, and Japan kills whales for 'scientific research', but the carcasses are commercially processed after the research has been carried out. Other potential threats facing minke whales, and indeed all cetacea, include pollution and reduction in prey abundance, perhaps as a result of over-fishing. Entanglement in fishing nets poses problems.

The global population is estimated at over 300,000 individuals, and there seems to be no cause for concern, since this species is not commonly hunted anymore. Many populations are on appendix 1 of CITES. Numbers have also been on the rise since the early 1900's because close competitors (other rorqual species) have been overhunted.

Classified as Least Concern (LC) on the IUCN Red List (1). Listed on Annex IV of the EC Habitats Directive. All whales are listed on Annex A of EU Council Regulation 338/97 and are therefore classed as if they are listed on Appendix 1 of CITES. Under the Fisheries Act of 1981 whaling is illegal in UK waters. All cetaceans (whales and dolphins) are fully protected under the Wildlife and Countryside Act, 1981 and the Wildlife (Northern Ireland) Order, 1985. The UK recognises the authority of the International Whaling Commission in matters concerning whaling regulations (4).

Further Reading

- Balaenoptera acutorostrata Lacépède, 1804, Encyclopedia of Life (accessed February 16, 2011)

- IUCN Red List (November, 2008)

- Cawardine, M., Hoyt, E., Fordyce, R.E. and Gill, P. (1998) Whales and Dolphins, The Ultimate Guide to Marine Mammals. Harper Collins Publishers, London.

- Burnie, D. (2001) Animal. Dorling Kindersley, London.

- UKBAP (June, 2002)

- WDCS (Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society) (June, 2002)

- Macdonald, D. (2001) The New Encyclopedia of Mammals. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Cawardine, M. (1995) Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises. Dorling Kindersley, London.

- Bruyns, W.F.J.M., (1971). Field guide of whales and dolphins. Amsterdam: Publishing Company Tors.

- Howson, C.M. & Picton, B.E. (ed.), (1997). The species directory of the marine fauna and flora of the British Isles and surrounding seas. Belfast: Ulster Museum. Museum publication, no. 276.

- Jefferson, T.A., Leatherwood, S. & Webber, M.A., (1994). FAO species identification guide. Marine mammals of the world. Rome: United Nations Environment Programme, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Kinze, C. C., (2002). Photographic Guide to the Marine Mammals of the North Atlantic. Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Reid. J.B., Evans. P.G.H., Northridge. S.P. (ed.), (2003). Atlas of Cetacean Distribution in North-west European Waters. Peterborough: Joint Nature Conservation Committee.

- Aphia-team

- Banks, R. C., R. W. McDiarmid, A. L. Gardner, and W. C. Starnes. 2003. Checklist of Vertebrates of the United States, the U.S. Territories, and Canada Search! Banks, R. C., R. W. McDiarmid, and A. L. Gardner. 1987. Checklist of Vertebrates of the United States, the U.S. Territories, and Canada. Resource Publication, no. 166. 79

- Bernhard Grzimek (1990) Grzimek's Encyclopedia of Mammals. McGraw-Hill: New York.

- Borges, P.A.V., Costa, A., Cunha, R., Gabriel, R., Gonçalves, V., Martins, A.F., Melo, I., Parente, M., Raposeiro, P., Rodrigues, P., Santos, R.S., Silva, L., Vieira, P. & Vieira, V. (Eds.) (2010). A list of the terrestrial and marine biota from the Azores. Princípia, Oeiras, 432 pp.

- Felder, D.L. and D.K. Camp (eds.), Gulf of Mexico–Origins, Waters, and Biota. Biodiversity. Texas A&M Press, College Station, Texas.

- Gordon, D. (Ed.) (2009). New Zealand Inventory of Biodiversity. Volume One: Kingdom Animalia. 584 pp

- Grizemek's Encyclopedia of Mammals. McGraw-Hill Publishing Co.

- Jefferson, T.A., S. Leatherwood and M.A. Webber. 1993. Marine mammals of the world. FAO Species Identification Guide. Rome. 312 p.

- Keller, R.W., S. Leatherwood & S.J. Holt (1982). Indian Ocean Cetacean Survey, Seychelle Islands, April to June 1980. Rep. Int. Whal. Commn 32, 503-513.

- Koukouras, Athanasios (2010). check-list of marine species from Greece. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Assembled in the framework of the EU FP7 PESI project.

- Lacépède, B-G, 1804. Histoire Naturelle des Cétacées, Paris: Plassan An XII, p. 134.

- MEDIN (2011). UK checklist of marine species derived from the applications Marine Recorder and UNICORN, version 1.0.

- Mead, James G., and Robert L. Brownell, Jr. / Wilson, Don E., and DeeAnn M. Reeder, eds. 2005. Order Cetacea. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 3rd ed., vol. 1. 723-743

- Mellinger, D., C. Carson. 2000. Characteristics of minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata) pulse trains recorded near Puerto Rico. Marine Mammal Science, 16(4): 739-756.

- North-West Atlantic Ocean species (NWARMS)

- Nowak, R.M. Walker's Mammals of the World, 5th Edition. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Perrin, W. (2011). Balaenoptera acutorostrata Lacépède, 1804. In: Perrin, W.F. World Cetacea Database. Accessed through: Perrin, W.F. World Cetacea Database at http://www.marinespecies.org/cetacea/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=137087 on 2011-02-05

- Ramos, M. (ed.). 2010. IBERFAUNA. The Iberian Fauna Databank

- Rice, Dale W. 1998. Marine Mammals of the World: Systematics and Distribution. Special Publications of the Society for Marine Mammals, no. 4. ix + 231

- Slijper, E.J. (1938). Die Sammlung rezenter Cetacea des Musée Royal d'Histoire Naturelle de Belgique Collection of recent Cetacea of the Musée Royal d'Histoire Naturelle de Belgique. Bull. Mus. royal d'Hist. Nat. Belg./Med. Kon. Natuurhist. Mus. Belg. 14(10): 1-33

- UNESCO-IOC Register of Marine Organisms

- Wilson, Don E., and DeeAnn M. Reeder, eds. 1993. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 2nd ed., 3rd printing. xviii + 1207

- Wilson, Don E., and F. Russell Cole. 2000. Common Names of Mammals of the World. xiv + 204

- Wilson, Don E., and Sue Ruff, eds. 1999. The Smithsonian Book of North American Mammals. xxv + 750

- van der Land, J. (2001). Tetrapoda, in: Costello, M.J. et al. (Ed.) (2001). European register of marine species: a check-list of the marine species in Europe and a bibliography of guides to their identification. Collection Patrimoines Naturels, 50: pp. 375-376