Northern Africa and biodiversity

Contents

- 1 Introduction Table 1: The biodiversity features of Northern Africa. (Source: Groombridge and Jenkins 2002, Hoekstra and others 2005, Mayaux and others 2004 and WRI 2005) Northern Africa falls within the arid belt extending from the Atlantic to central Asia. Aridity and the geographical location of its six countries determine its biodiversity. The occurrence of long shores with vast coastlines, oases in the Sahara and the different landforms create considerable habitat and species diversity. The sub-region is vulnerable to desertification (Northern Africa and biodiversity) and drought. However, due to particular climatic conditions, it is rich in biodiversity, with many species being endemic. The total number of known endemic species of flora is 1,129, of mammals 22, of birds 1, of reptiles 20, and of amphibians 4. At the country level, the highest numbers of endemic biota are mostly found in Morocco, with recorded higher plant species ranging from 1,875 in Libya to 3,675 species in Morocco. Mammals range from 76 species in Libya to 267 species in Sudan. The number of bird species varies from 80 in Libya to 938 in Sudan. Reptiles and amphibians are still under-investigated in most of the countries, but the numbers of known reptile and amphibian species in Egypt are 83 and 6, respectively.

- 2 Challenges faced in realizing opportunities for development

- 3 Strategies for enhancing biodiversity values

- 4 Further reading

Introduction Table 1: The biodiversity features of Northern Africa. (Source: Groombridge and Jenkins 2002, Hoekstra and others 2005, Mayaux and others 2004 and WRI 2005) Northern Africa falls within the arid belt extending from the Atlantic to central Asia. Aridity and the geographical location of its six countries determine its biodiversity. The occurrence of long shores with vast coastlines, oases in the Sahara and the different landforms create considerable habitat and species diversity. The sub-region is vulnerable to desertification (Northern Africa and biodiversity) and drought. However, due to particular climatic conditions, it is rich in biodiversity, with many species being endemic. The total number of known endemic species of flora is 1,129, of mammals 22, of birds 1, of reptiles 20, and of amphibians 4. At the country level, the highest numbers of endemic biota are mostly found in Morocco, with recorded higher plant species ranging from 1,875 in Libya to 3,675 species in Morocco. Mammals range from 76 species in Libya to 267 species in Sudan. The number of bird species varies from 80 in Libya to 938 in Sudan. Reptiles and amphibians are still under-investigated in most of the countries, but the numbers of known reptile and amphibian species in Egypt are 83 and 6, respectively.

The major part of the biodiversity of Northern Africa is drawn from the pool of species broadly represented in the Mediterranean basin. There are locations of endemism in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia accounting for about a fifth of the plant species in the sub-region (Table 1). Since Northern Africa has been the location of successive civilizations over a period of up to eight millennia, the landscape and its biodiversity are highly transformed in the areas of human settlement.

Hundreds of plant species are used in traditional medicine and represent a wealth of genetic resources rarely found elsewhere. Pharmacopoeial plants include Hyoscyamus muticus, Urginea maritima, Colchicum autumnale, Senna alexandrina, Plantago afra, Juniperus communis, Anacyclus pyrethrum, and Citrullus colocynthis. Endemic plants, some of which are endangered, include Argania spinosa, Arbutus pavari, Cedrus atlantica, antieuphorbium, Thymus algeriensis, and Thymus broussonettii (Batanouny 1999). To date, they have not been studied in detail or valued. About 70 percent of wild plants are known to be useful in more than one context, of which 35 percent are under-utilized.

Challenges faced in realizing opportunities for development

The major underlying threats to biodiversity include population growth, agricultural and urban expansion to ecologically important areas, poverty, unsustainable use of biota, and macro-scale stresses such as drought. Emerging factors threatening biodiversity include IAS and the use of genetically modified (GM) species, which may result in an increasing homogenization of the biota (Hegazy and others 1999). The sections Genetically modified crops in Africa and Invasive alien species in Africa consider some of these challenges. The depletion of underground water level in many countries has led to the deterioration and loss of unique water springs and wetlands with their associated biota.

Human settlement patterns and activities are located close to available water resources and compete with biodiversity. In such a dry landscape, perennial rivers, oases and ephemeral moist areas, such as wadis, are inevitably the focus of people and biodiversity. Northern Africa straddles the migratory bird flyways between Europe and SSA and is an important stopping-off point for an estimated billion migratory raptors, passerines and Palaearctic waterbirds.

The Nile is a key biodiversity corridor across the arid Sahara and Sahel belt, but is highly impacted by human actions in its lower reaches. The functioning of this system (specifically the periodic flooding and discharge to the sea, which brought large amounts of sediment and nutrients to the river banks and delta) was substantially altered by completion of the Aswan Dam in 1934 and the subsequent construction of the Aswan High Dam in 1965. As a result of the intensive water use in Egypt, there is virtually no discharge into the Mediterranean Sea, and only small pockets of relatively undisturbed coastal marshland remain in the delta. New irrigation schemes may further diminish water supplies in the lower Nile system and impose additional threats to the biodiversity. Similarly other development projects, including those related to hydropower, will increase demands on the existing water resources and this, in turn, will exert additional pressures on the basin’s ecosystems and biodiversity.

In the coming decade, the abuse of agrochemicals and uncontrolled fishing and hunting are expected to Euphorbia echinus, Euphorbia resinifera, Senecio put more pressure on the fragile ecosystems and the threatened endemic species, particularly in hotspots. Protection of critical sites is imperative. The growing need for transborder conservation is also an emerging issue in some areas, such as the borders between Egypt and Sudan, and between Morocco and Algeria.

Strategies for enhancing biodiversity values

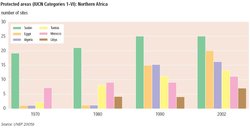

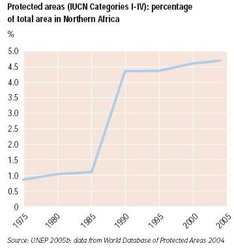

There are ongoing schemes to establish protected areas and biosphere reserves throughout the sub-region. The total area of official protected areas remains less than 5 per cent of the land area, which is below the Convention on Biological Diversity CBD standard of 10 per cent. Nevertheless, some countries aim to increase their protected areas to more than 15 per cent within the next three decades. Currently, Northern Africa has over 90 protected areas and 12 biosphere reserves. Many other sites are proposed for protection.

Further reading

- Groombridge, B. and Jenkins, M., 2002. World Atlas of Biodiversity: Earth’s Living Resources in the 21st Century. University of California Press, Berkeley.

- Hegazy,A. K., Fahmy,A.G. and Mohamed, H. M., 2001. Shayeb El-Banat mountain group on the Red Sea coast: a proposed biosphere reserve.

- Hoekstra, J.M., Boucher, T.M., Ricketts,T.H. and Roberts, C., 2005. Confronting a biome crisis: global disparities of habitat loss and protection. Ecology Letters. 8, 23-9. Symposium on Natural Resource Conservation in Egypt and Africa, Cairo, Egypt, 19-21 March

- IUCN (undated – b). North Africa Programme. IUCN – The World Conservation Union.

- Mayaux, P., Bartholomé, E., Fritz, S. and Belward, A., 2004. A new landcover map of Africa for the year 2000. Journal of Biogeography. 31(6), 861-77.

- UNEP, 2005b. GEO Africa Data Portal. United Nations Environment Programme.

- UNEP, 2006. Africa Environment Outlook 2

- WRI, 2005. EarthTrends: The Environmental Information Portal. World Resources Institute, Washington, D.C.

|

|

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |