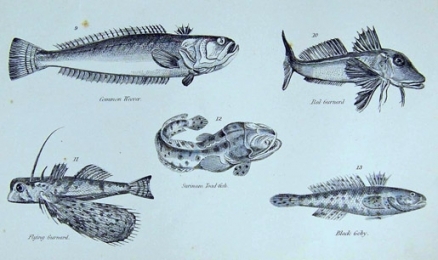

Fish morphology (Biodiversity)

Contents

Fish morphology

Fish morphology refers to the variety of anatomical design among fish species. Body architecture can be discussed in terms of the characteristic depth, predation style and other swimming specializations required for the survival success of a given speces. For example, the type, size and arrangement of a fish fins are inextricably related to their ecological niche. All fins (except the adipose fin) are supported internally by fin rays, but the bony fishes typically have flexible, segmented and branched fins, while the cartilaginous fishes (sharks and sting-rays) have stiff, unsegmented fins.

Body designs

Fish are amazingly diverse in their morphology. Some primitive species, such as the lampreys, lack jaws, scales and paired fins. Others, like the sharks do not have bones, but possess a cartilaginous skeleton instead. They come in all shapes and sizes, from the expected, to the bizarre. Form and function work together and examination of basic body shapes gives us insight to fish lifestyles. Most fish fall into one of six basic body forms: the rover predator, lie-in-wait predator, surface oriented, bottom dweller, deep-bodied or eel like.

Rover predator

A streamlined body, pointed head, narrow caudal peduncle and a forked tail are the characteristics of this typical fish. In fact, this is the shape most people think of when they think of a fish! Their evenly distributed fins provide stability and maneuverability, which is important for endurance swimming and actively seeking prey. This body type is typical of stream dwellers, which forage in fast water. Common examples of this body form are the trouts (family Salmonidae), some minnows (family Cyprinidae), tuna (family Scombridae) and swordfish (family Xiphiidae).

Lie-in-wait predator

These are typical ambush predators on fast moving prey. Their bodies are streamlined and elongate, with a flattened head and a mouth full of pointy teeth. In some families with this body plan, such as the pikes, the dorsal and anal fins are inserted far toward the rear, very near the caudal fin. This fin arrangement allows the normally still fish to generate rapid acceleration when the large muscle mass of the cylindrical body pushes against the water with the combined area of the dorsal, caudal and anal fins. In this way, they are able to thrust forward at high speeds to attack a passing fish. Their cryptic colouration and secretive behaviour helps to conceal them from suspecting prey. The pikes (family Esocidae), gars (family Lepisosteidae) and the marine barracudas (family Sphyraenidae) have this body plan.

Surface oriented

The upward turned mouths of these fish allow them to exploit plankton and small fish at the surface of the water. These fish are typically small in size, with a dorsoventrally flattened head, large eyes, streamlined body and a dorsal fin that occurs far back on the body. In stagnant water, this body design is ideal for taking advantage of the rich oxygen supply at the air-water interface. The Arctic cod (family Gadidae) and many killifishes (family Fundulidae) have this body form.

Bottom oriented

As the name suggests, this body plan is suited for living in benthic habitats. Many body shapes accomplish this goal, but generally fish with this body plan have a reduced or absent swim bladder and are flattened. Bottom fishes can be further classified into five categories: bottom rovers, bottom clingers, bottom hiders, flatfish and rattails.

Bottom rovers have a shape similar to the rover-predator, but have a flattened head, humped back and enlarged pectoral fins. These fish often possess barbels or "whiskers" with taste buds to locate prey in muddy water. The mouth shapes of these fish vary to exploit different food sources found on the bottom. Catfishes (family Ictaluridae) have large, terminal mouths, while sturgeons (family Acipenseridae) have fleshy, protrusible lips to suck plant and animal material off the bottom.

Bottom clingers, such as the sculpins (family Cottidae), have enlarged, closely spaced pelvic fins and specialized pectoral fins which help to anchor them to the bottom. The pectoral fins of gobies (family Gobiidae) and clingfishes (family Gobiesocidae) are actually modified into suction cups.

Bottom hiders are typically found under rocks, in crevices or remain still at the bottom. Darters (family Percidae) and blennies (family Blennidae) have this strategy.

Flatfish are also specially designed for benthic habitats. Flounders (family Pleuronectidae) are unusual looking, deep-bodied fish with both eyes on one side of their head. Their mouth is twisted for feeding on the bottom. Skates (family Rajidae) and rays (family Dasyatidae) are also flattened, but have a completely ventral mouth.

Finally, rattail shaped fish as seen in the grenadiers (family Macrouridae), brotulas (family Ophidiidae) and chimaeras (family Chimaeridae) have large pointy snouts, large pectoral fins and pointed rat-like tails. These fish inhabit the deep sea where they prey on benthic invertebrates.

Deep-bodied

This deepened body form is adapted for maneuverability in spatially complex habitats. The pelvic fins are moved far forward, so that the pectorals and pelvics together form a single control surface for turning, stopping and holding position. The mouth is small, the eyes large and the snout short, adaptations for feeding on small invertebrates at the bottom or in the water column. These fish are not designed for speed and instead rely on their maneuvering ability and spiny fins for protection from predators. The butterflyfish (family Chaetodontidae), which live in coral reefs, and the sunfish (family Centrarchidae) have this body form.

Eel-like

Elongate bodies, rounded heads and rounded tails allow these fish to explore a diversity of habitats including crevices and holes in rocky and reefed areas, soft muddy bottoms and densely vegetated areas. Long dorsal and anal fins allow these fish to exploit open water habitats as well. Eels (family Anguillidae), loaches (family Balitoridae) and gunnels (family Pholidae) have this body plan.

External anatomy

Although they are incredibly diverse in form, most fish share common morphological characteristics, such as fins, gills, scales, lateral line and caudal peduncle. Two basic body forms show the anatomical features of most fish: the soft ray-finned fish and the spiny ray-finned fish.

The ancestral body plan, represented by the soft-rayed fish, is best adapted for endurance swimming and cruising. These fish typically have one dorsal fin and an adipose fin.

The laterally compressed and dorsoventrally deepened body of the spiny-rayed fishes is adapted for maneuverability in spatially complex habitats. These fish typically have two dorsal fins; the first with spiny projections and behind it, a soft-rayed fin.

Caudal Peduncle

The caudal peduncle is the slender region between the base of the last dorsal and anal fin rays and the caudal fin base. The depth of the caudal peduncle is significant for propulsion.

Lateral Line

The lateral line is a sensory system made up of mechanoreceptors that detect vibrations in the water around the fish.

Fins

Fish have several fins, including the dorsal, adipose, caudal, anal, pelvic and pectoral fins. Each of these fins plays an important role in maneuvering, braking, turning or propulsion. Fins are often highly variable in function, position and shape.

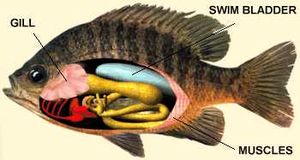

Internal anatomy

Internal anatomy

Gills

Gills are the main site for gas exchange in almost all fish. They also serve an important function in osmoregulation and ion exchange.

Muscles

Fish require a large muscle mass for swimming and maintaining activity for sustained periods of time. In fact, the muscles of the body and tail make up a significant portion of their total body mass. The body muscles can be divided into red and white muscle fibre, each serving a different purpose.

Red muscle fibre is best suited for prolonged, slow contractions and endurance swimming. Fish that are active for long periods at a time typically have a lot of this muscle tissue.

In contrast, white muscle fibre is best suited for short-term, rapid contractions. These are thicker than red fibre, have a poorer blood supply and lack an oxygen carrying pigment like myoglobin. These muscles are most useful for short bursts of swimming and are most common in sluggish fish.

Swim bladder

The swim bladder, or gas bladder, is an important gas-filled sac found in the dorsal portion of the body cavities of many bony fishes. It functions to maintain bouyancy. Some sedentary, benthic fishes lack a swim bladder.

Otoliths

Otoliths are calcified structures found in the inner ears of fishes. These structures have layers, much like an onion. Using microscopy to count the layers and measure their width, allows fish biologists to age a fish, as well as assess its rate of development in relation to other individuals. For young fish, the layers can represent daily growth increments.

Scale types

Scales

Scales are usually considered a fundamental part of a fish, yet not all fish have them! In fact, fish can have large, bony plates, small, fine scales, modified scales, or no scales at all. The size and type of scales which a fish possesses is indicative of its lifestyle. Active fish that live in fast moving streams, such as trout, often have many, fine scales. In contrast, perch and sunfish, which live in quiet water and have, fewer, larger scales. Scales can be classified into four different types: ganoid, cycloid, ctenoid and placoid.

| Ganoid scales This scale type is typically found on gars (family Lepisosteidae). This is the ancestral scale of the bony fishes. These heavy scales are covered with a hard enamel. |

|

| Cycloid scales Cycloid scales are round, flat and thin, with a smooth rear edge. They are smooth to the touch. Trout, minnows and herrings have this type of scale. |

|

|

Ctenoid scales |

|

|

Placoid scales |

Fin types

Introduction

The types, sizes and arrangement of a fishes' fins are inextricably related to their ecological niche. All fins (except the adipose fin) are supported internally by fin rays, but the bony fishes typically have flexible, segmented and branched fins, while the cartilaginous fishes (sharks and rays) have stiff, unsegmented fins.

Adipose fins

Adipose fins

The adipose fin, located between the dorsal and caudal fins, is typical of the trouts (family Salmonidae), smelts (family Osmeridae) and the lanternfishes (family Myctophidae). It is small and fleshy, without stiffening rays. Its function is largely unknown, but it may help swimming ability in the post larval stage of development, when other fins are still developing.

Anal fins

Anal fin

The anal fin is usually long. It can be used for propulsion and maneuvering during swimming. This fin is also erected during aggressive interactions.

Caudal fins

Caudal fins

Caudal_Fin.gif

The caudal fin is often thought of as the tail. This fin is most important in propulsion, but is also used by some fish, such as salmons, for digging nests. The shape of the caudal fin is related to the fish's swimming ability. Fast swimming fish, such as the tuna, have a sleek, quarter-moon shaped tails. Strongly forked tails are efficient for activity and sustained swimming, while square, rounded or slightly forked tails are found in deep-bodied and bottom fish. Caudal fins can have these various different external shapes, but there are also basic differences in the internal structure:

The heterocercal tail is the most primitive form and is typical of the cartilaginous fishes (class Elasmobranchii) and the sturgeons (family Acipenseridae). Here, the vertebral column extends into the upper lobe of the caudal fin, making it longer than the lower lobe.

The homocercal tail is characteristic of most of the bony fishes (class Osteichthyes). In this type of tail, the vertebral column ends in a modified vertebrae (called the urophore complex), which supports a symmetrical, fan-like tail.

The protocercal and leptocercal caudal fins are similar in appearance and extend to join the dorsal and anal fins forming one confluent fin. Although they look similar, these tails have different evolved independently in different groups. The protocercal tail is found in the lampreys (family Petromyzontidae), while the rattails (family Chimaeridae) have leptocercal tails.

Dorsal fins

Dorsal fins

As its name suggests, the dorsal fin runs down the length of a fish's back. It is usually the longest fin and is used for stability while swimming. The dorsal fin can also be used for propulsion, maneuvering during locomotion, and can be erected during aggressive interactions. Fish can have one, two or three dorsal fins, the first may or may not be spiny.

Pectoral fins

Pectoral fins

Paired pectoral fins, one located on each side of the fish, are attached to the shoulder girdle, just behind the head. These fins are variable in both function and shape. During locomotion, they are used for propulsion, turning and braking. Some species even use these fins to push a fresh, oxygenated supply of water across their developing eggs. Bottom fish often have rounded and broad pectoral fins that are ventral in position, while fast moving fish tend to have long, pointed pectorals. Rounded fins are found in fish that need increased surface area for stability when swimming. Accurate maneuvering is accomplished by pectoral fins that are located high up on the sides of deep-bodied fish. Occasionally, enlarged pectoral fins serve as a defense to startle predators, or to warn them of poisonous spines.

Pelvic fins

In general, the paired pelvic fins are located on the lower part of the fish body. However, the pelvic fins are highly variable in both location and function. Like the pectorals, the pelvic fins can be used for propulsion, turning and braking. In some fish, these fins are modified, reduced or even absent. Reduced or absent pelvics allow eel-like fish to squeeze through small crevices. In bottom fish, such as the sculpins, these appendages are modified for holding on to the substrate. The pelvic fins of sharks and rays is modified into a sperm transfer appendage.

Pelvic fins can appear in an abdominal (toward the rear of the fish), thoracic (just under the pectoral fins) or jugular (in front of the pectoral fins) position.

Finlets

In some fast swimming fishes, such as the tuna or the mackerel, the rear portion of the dorsal and anal fins are specialized into many finlets. When the fish is swimming, the main fins collapses into a slot to reduce drag, while the finlets act to stabilize the motion.