Layard's beaked whale

Layard's beaked whale (also well known as the Strap-toothed whale; scientific name: Mesoplodon layardii) is one of 21 species of beaked whales (Hyperoodontidae or Ziphiidae), medium-sized whales with distinctive, long and narrow beaks and dorsal fins set far back on their bodies. They are marine mammals within the order of cetaceans.

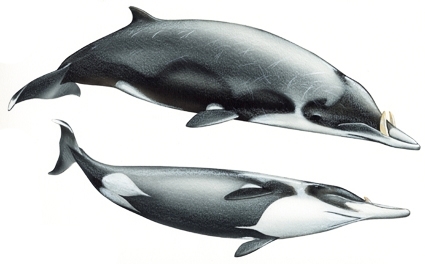

Stranded Strap-toothed Whale. Source: New Zealand Department of Conservation Stranded Strap-toothed Whale. Source: New Zealand Department of Conservation

|

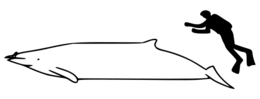

Size comparison of an average human against Layard's beaked whale. Source: Chris Huh Size comparison of an average human against Layard's beaked whale. Source: Chris Huh

|

|

Conservation Status: |

|

Scientific Classification Kingdom: Animalia |

|

Common Names: |

One of the largest and most distinctly marked of the beaked whales, the strap-toothed whale is named for the unique and somewhat bizarre teeth of the adult male. In common with other beaked whales, only two teeth become well developed, one on each side of the lower jaw, but in the male strap-toothed whale these grow up and over the upper jaw, reaching to over 30 centimetres in length, and curling over the top of the jaw so that the mouth is clamped nearly shut. Female and immature strap-toothed whales have no visible teeth, making them more difficult to distinguish from other beaked whale species.

The teeth of the male, not needed for feeding, have developed into weapons, with adult males often bearing scars from fights. However, the adaptive significance of this species' unique tooth shape has never been fully explained, although it is not thought to hinder feeding, despite severely restricting the male's gape.

Beaked whales are rarely seen in the wild, and so very little is known about the biology of these elusive species. The strap-toothed whale may be solitary or occur in small groups of two to three individuals.

The diet of the strap-toothed whale is thought to comprise mainly squid, as well as some fish and crustaceans, and like other beaked whales it is believed to be a suction feeder, sucking prey into the mouth and swallowing it whole.

Contents

Physical Description

Adult strap-toothed whales exhibit a body mass ranging between 907 and 2721 kilograms and are 5.0 to 6.2 meters (m) in length. Newborns tend to be 2.5 to 3.0 m in length.

The body of the strap-toothed whale is robust and spindle-shaped, with a small dorsal fin about two-thirds of the way down the body, small flippers, and an unnotched tail fluke with pointed tips. Unusually, the species shows the reverse of typical cetacean colouration, being dark below and lighter above. The body is mainly black, with a white throat and upper back, white front to the beak, a white patch around the genital area, and a dark mask over the eyes and melon. The pattern of light and dark areas is reported to be reversed in juveniles.

The most distinctive morphological characteristic of Strap-toothed whales is the single pair of mandibular teeth that are found only in adult males. These teeth curve over the upper jaw allowing the mouth to open only 11 to 13 cm. It is assumed that these teeth are used for intraspecific competition between males due to the high number of scars observed on the males. (MacLoed, 2000; Sekiguchi, Klages, and Best, 1996)

Other Physical Features: Endothermic; Homoiothermic; Bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: Sexes shaped differently; Ornamentation

Behaviour

Strap-toothed whales tend to shy away from boats, therefore they are rarely seen in the wild. When they are observed it is reported that they slowly sink below the surface of the water and rise again 150 to 250 meters away. Sometimes an individual will perform a lateral roll, exsposing a single flipper. Typically the dives last 10 to 15 minutes. (Bannister, Kemper, and Warnke, 2001; Texas AandM University-Corpus Christi, 2002)

The large tusks in adult males are presumably a form of visual or tactile communication. Other toothed whales also use echolocation. It is likely that there are some forms of accoustic communication within the species, also. (MacLoed, 2000)

Key Behaviors: natatorial; diurnal; motile

Communication Channels: visual; tactile; acoustic

Perception Channels: visual; tactile; acoustic; echolocation; chemical

Lifespan

Lifespan of Strap-toothed whales is unknown. However, members of other species in the genus are reported to have lived from 27 to 48 years. (Bannister, Kemper, and Warnke, 2001; Nowak, 1999)

Reproduction

The mating system of Strap-toothed whales has not been observed, so that little is known about their reproductive behavior. It is thought that mating occurs in summer and calving occurs in summer to autumn after a 9 to 12 month gestation period. (Bannister, Kemper, and Warnke, 2001)

The female gives birth to a single calf in spring or summer, after a gestation period of around nine to twelve months, with the calf measuring about 2.2 metres at birth. Strap-toothed whales breed once per year.

There have been no studies of parental care in Strap-toothed whales. However, groups consisiting of a single female with calf pairs are often observed. In general, newborn cetaceans are precocial. They are able to follow the mother from birth. Although the female nurses the offspring, the duration of lactation is not known for this species. The role of the male in parental care is likewize unknown. (Bannister, Kemper, and Warnke, 2001)

Key Reproductive Features: Iteroparous; Seasonal breeding; Gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); Sexual; Fertilization; Viviparous

Distribution and Movements

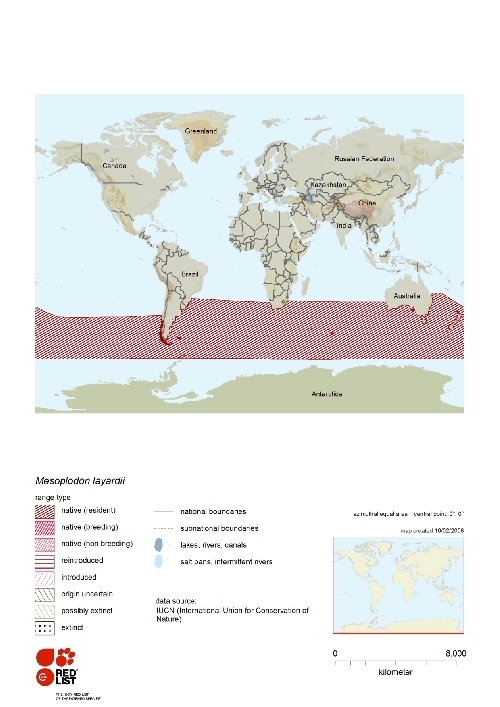

Layard's beaked whale tends to live in the cold temperate waters of the Southern Hemisphere.

A majority of the sightings have been around Australia, New Zealand, and Tasmania, but there have also been sightings in South Africa, Namibia, the Falkland Islands, Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay. (Sekiguchi, Klages, and Best, 1996; Texas AandM University-Corpus Christi, 2002)

Habitat

Strap-toothed whales are found in deep oceanic waters of the temperate to subantartic regions. They may use adjacent waters for feeding and calving. (Bannister, Kemper, and Warnke, 2001)

Habitat Regions: Saltwater or marine

Feeding Habits

Twenty-four species of oceanic squid, along with some deep-sea fishes make up the main diet of Strap-toothed whales; mollusks are also consumed.

Confusion and fascination surround the feeding habits of these whales due to the enlarged mandibular teeth in the males. At first they were thought to interfere with feeding, but it is now thought that they may act as "guide rails" to send food to the throat. Even this hypothesis is questioned because it is quite possible that Layard's beaked whale, like other beaked whales, suck food into their mouths, regardless if how far they can open their mouths. (Sekiguchi, Klages, and Best, 1996)

Predation

These whales may be prey for Killer whales. (Bannister, Kemper, and Warnke, 2001)

Economic Importance for Humans

These marine mammals are not reported to have any positive economic impact on humans. These animals are not reported to have any negative impacts on humans.

Threats and Conservation Status

The Strap-toothed whale is thought to be relatively common, but a lack of information on its global abundance or population trends makes it difficult to assess its conservation status. However, beaked whales appear to have naturally quite low populations, meaning even low-level threats can have unsustainable impacts.

The strap-toothed whale is not directly hunted, although bycatch in gillnets and longline fisheries is likely occurring. Other threats may include noise pollution, which has been linked to mass strandings of other beaked whale species, as well as chemical pollution,and ingestion of plastic waste.

The strap-toothed whale's preference for deep waters may have helped protect it in the past from the threats facing more coastal species, but as fisheries expand into deeper waters the species may face increasing competition for its squid prey, and an increased threat from entanglement in nets.

In 1982, the National Stranding Contigency Plan was designed to outline scientific objectives and appropriate biological/veterinary research activies for the stranded whales. (Bannister, Kemper, and Warnke, 2001)

Another focus for the conservation efforts lies in the development of objectives and agreements to protect cetaceans and their environment under federal and state laws. Strap-toothed whales are listed on Appendix II of CITES. (Bannister, Kemper, and Warnke, 2001)

The strap-toothed whale is listed on Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), meaning international trade in this species should be carefully monitored and controlled.

Research is needed to determine the impacts of the threats to the strap-toothed whale, in addition to further investigating its biology, seasonal movements and population trends. International efforts may be needed to control current and potential threats to the species, in particular the development of fisheries directed at its deep-sea squid prey.

IUCN Red List classifies the species asData Deficient. The US Federal List note: No special status. CITES lists the species inAppendix II.

References

- Mesoplodon layardii (Gray, 1865). Encyclopedia of Life. Accessed 11 May 2011.

- Flohr, A. 2004. Mesoplodon layardii (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed May 11, 2011 .

- Taylor, B.L., Baird, R., Barlow, J., Dawson, S.M., Ford, J., Mead, J.G., Notarbartolo di Sciara, G., Wade, P. & Pitman, R.L. 2008. Mesoplodon layardii. In: IUCN 2010. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2010.4. . Downloaded on 15 May 2011.

- Perrin, W.F., Würsig, B. and Thewissen, J.G.M. (2002) Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press, San Diego, California.

- Macdonald, D.W. (2006) The Encyclopedia of Mammals. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- CITES (May, 2009) http://www.cites.org

- Jefferson, T.A., Leatherwood, S. and Webber, M.A. (1993) FAO Species Identification Guide. Marine Mammals of the World. FAO, Rome.

- Convention on Migratory Species: Mesoplodon layardii (May, 2009)

- Tinker, S.W. (1988) Whales of the World. EJ Brill Publishing Company, New York.

- The Beaked Whale Resource: Strap-toothed whale Mesoplodon layardii (May, 2009)

- Carwardine, M., Hoyt, E., Fordyce, R.E. and Gill, P. (1998) Whales and Dolphins: The Ultimate Guide to Marine Mammals. HarperCollins Publishers, London.

- Martin, A.R. (1990) Whales and Dolphins. Salamander Books, London.

- Nowak, R.M. (1991) Walker's Mammals of the World. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London.

- Bannister, J.L., Kemper, C.M. and Warneke, R.M. (1996) The Action Plan for Australian Cetaceans. Australian Nature Conservation Agency, Canberra.

- Sekiguchi, K., Klages, N.T.W. and Best, P.B. (1996) The diet of strap-toothed whales (Mesoplodon layardii). Journal of Zoology, 239: 453 - 463.

- Reeves, R.R., Smith, B.D., Crespo, E.A. and Notarbartolo di Sciari, G. (2003) Dolphins, Whales and Porpoises: 2002-2010 Conservation Action Plan for the World's Cetaceans. IUCN/SSC Cetacean Specialist Group, IUCN, Gland.

- Banks, R. C., R. W. McDiarmid, and A. L. Gardner. 1987. Checklist of Vertebrates of the United States, the U.S. Territories, and Canada. Resource Publication, no. 166. 79

- Bannister, J., C. Kemper, R. Warnke. 2001. The Action Plan for Australian Cetaceans (On-line ). Accessed 11/04/02.

- MacLoed, C. 2000. Species Recognition as a Possible Function for Variations in Position and Shape of the Sexually Dimorphic Tusks of Mesoplodon Whales. Evolution, 54/6: 2171-2173. Accessed 12/03/02.

- Mead, James G., and Robert L. Brownell, Jr. / Wilson, Don E., and DeeAnn M. Reeder, eds. 2005. Order Cetacea. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 3rd ed., vol. 1. 723-743

- Nowak, R. 1999. Walker's Mammals of the World, Sixth Edition. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Perrin, W. (2010). Mesoplodon layardii (Gray, 1865). In: Perrin, W.F. World Cetacea Database. Accessed through: Perrin, W.F. World Cetacea Database on 2011-05-05

- Rice, Dale W. 1998. Marine Mammals of the World: Systematics and Distribution. Special Publications of the Society for Marine Mammals, no. 4. ix + 231

- Sekiguchi, K., N. Klages, P. Best. 1996. The Diet of Strap-toothed Whales (Mesoplodon layardii). Journal of Zoology,London, 239/3: 453-463.

- The Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society. 2002. "The Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society" (On-line ). Accessed 11/04/02.

- UNESCO-IOC Register of Marine Organisms

- Wilson, Don E., and DeeAnn M. Reeder, eds. 1993. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 2nd ed., 3rd printing. xviii + 1207

- Wilson, Don E., and F. Russell Cole. 2000. Common Names of Mammals of the World. xiv