Inequity and growth

| Topics: |

The current economic textbook conviction is that income or wealth inequity is good for economic growth. The idea of incentive driven growth permeates the development and growth agenda so much that equity is rarely discussed in relation to economic growth. The works of Kaldor and Kuznets in the 1950s and 1960s seemed to help establish the idea that equity and growth could not be achieved simultaneously. Robert Solow’s landmark work on growth theory added to the equity-blind growth agenda so ubiquitous today. The net result was the belief that 1) inequity induced growth, 2) growth would eventually reduce national inequity and 3) by pursuing growth all nations would converge to the same growth path, hence reducing international inequity.

For his part, Kuznets found (to his surprise) that as Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States moved from agrarian to industrial societies the income gap increased at first, peaked several decades after industrialization began, and then decreased as full industrialization approached. His inverted U relationship between income growth and equality – eventually became known as the Kuznets Curve, and despite the fact that he warned his results were “speculative” this relationship has come to represent the traditional growth path of nations.

Kaldor following similar assumptions formalized saving rates as an increasing function of real income, and the idea that profits largely outweighed workers’ savings. Building on this assumption, Kaldor used empirical data to show that productivity growth in the 1950s and 1960s in Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries was largely a function of investment behavior. The logic that capitalists and high-income earners had a greater marginal propensity to save, combined with the importance of investment for growth, led to the conclusion that inequality fostered growth.

Robert Solow’s growth theory suggested that with low initial labor and capital productivity it was assumed that less developed countries (LDCs) would ‘grow’ at a faster rate and attract the bulk of international investment. The assumption remains today and is often invoked, along with the theory of comparative advantage, as the rational for liberalization policies. The long run assumption is a world without artificial barriers to trade (Free trade), where both the developed countries and the LDCs would converge to the same growth path.

Taken together, these three streams of thought have helped to establish the equity-blind growth prescription so ubiquitous today, but the theories that Kuznets, Kaldor, and Solow divined do not stand up to recent empirical findings.

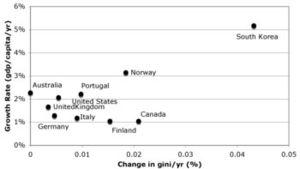

Recent data has shown the Kuznets Curve hypothesis is on shaky ground, particularly within many OECD nations, which over the past 20 years have experienced a sharp increase in inequity despite strong economic growth (see Figure 1). Earnings inequality has accelerated most notably in the US, UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

The bulk of more recent empirical work investigating Solow’s idea of growth convergence has generally shown that (1) cross-country convergence has been non-existent to minimal; (2) poor countries have not seen higher investment rates due to greater marginal return; and (3) inequality can hinder or promote economic growth in the near term, but seems to come down on the side of hindering in the longer term.

The development policies of capital accumulation of the 1950’s and 1960’s, the end to import substitution projects by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank in the 1980’s and the current neoliberal policies, have all greatly affected the development landscape over the past 50 years, often ignoring (implicitly and/or explicitly) equity issues in pursuit of growth.

The vital role played by institutions in Japan and Korea’s development, the recent acknowledgment of the IMF that their liberalization policies may have exacerbated the 1997-98 global financial crisis, and the astounding fact that global poverty and inequity are likely to have worsened over the past 20 years of liberalization are all reasons why the current development policy prescriptions should be called into question. The positive growth-equity results in the past 20 years have been mainly the result of institutions, not markets, and the lessons of recent empirical work into growth and equity must find their way into economic policy.

Further Reading

- Aghion, P., E. Caroli, et al., 1999. "Inequality and economic growth: The perspective of the new growth theories." Journal of Economic Literature, 37(4):1615-1660.

- Forbes, K. J., 2000. "A reassessment of the relationship between inequality and growth." American Economic Review, 90(4):869-887.

- Kaldor, N., 1958. Capital Accumulation and Economic Growth. The Essential Kaldor. New York, Holmes and Meier: 229-281.

- Kaldor, N., 1967. Strategic Factors in Economic Development. Ithaca, NY, Cornell University. ISBN: 0875460240

- Kuznets, S., 1955. "Economic Growth and Income Inequality." American Economic Review, 45(1):1-28.

- Prasad, E., K. Rogoff, et al., 2003. Effects of Financial Globalization on Developing Countries: Some Empirical Evidence. Washington D.C., International Monetary Fund.

- Skott, P. and P. Auerbach, 1995. "Cumulative causation and the 'new' theories of economic growth." Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 17(3):381-402.

- Stiglitz, J. E., 2002. Globalization and its discontents. New York, W.W. Norton. ISBN: 0393324397

- Wade, R. H., 2004a. "Is globalization reducing poverty and inequality?" World Development, 32(4):567-589.

- Wade, R. H., 2004b. "On the Causes of Increasing World Poverty and Inequality, or Why the Matthew Effect Prevails." New Political Economy, 9(2):163-188.

This Informational Box is an excerpt from An Introduction to Ecological Economics by Robert Costanza, John H Cumberland, Herman Daly, Robert Goodland, Richard B Norgaard. ISBN: 1884015727