Snake River

| Topics: |

Geology (main)

|

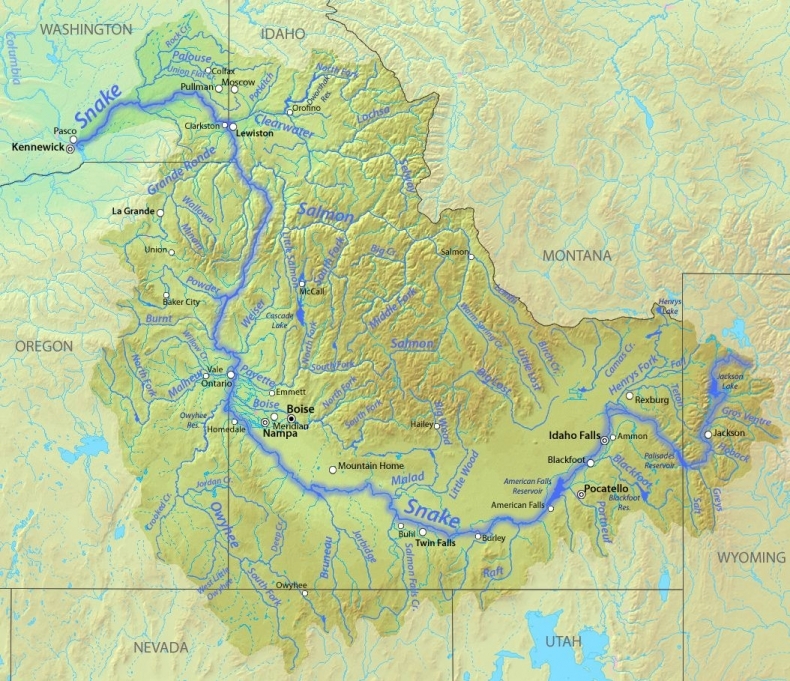

The Snake River is one of the major watercourses in the western USA, with headwaters rising in Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming, ultimately discharging to the Columbia River. The catchment area of the Snake River and its tributaries span portions of seven states, encompassing an area of 278,450 square kilometers.

One of the main conservation and water quality issues is reversing the agricultural diversions of the Snake, which actions would correspondingly reduce agricultural runoff of nitrate, herbicides and pesticides; other desirable conservation issues would be removal of hydroelectric dams, which inundate habitat and interfere with fish migration.

Source: USGS/ modified for Wikimedia Commons

Contents

Hydrology

The Snake River discharges to the Columbia River with a mean flow of approximately 1500 cubic meters per second, at its discharge in the state of Washington. Chief tributaries of the Snake River are Salt River, Gros Ventre River, Portneuf River, Owyhee River, Malheur River, Powder River, Wood River, Grande Ronde River, Henrys Fork, Malad River, Boise River, Payette River, Salmon River, Clearwater River and the Palouse River

Wild bison grazing on the Snake River Plain, Wyoming. @ C.Michael Hogan

Wild bison grazing on the Snake River Plain, Wyoming. @ C.Michael Hogan

From Jackson Lake to King Hill the Snake River travels about 810 kilometers, with an average gradient of slightly less than two percent. Surface water as well as groundwater exits the eastern plain of the upper Snake basin via the Snake River channel. Surface streamflow from six tributaries north of the Snake River Plain fails to reach the Snake River, but is lost via evapotranspiration and infiltration to groundwater underlying the Plain. Approximately 4.8 million acre-feet of water per year enters Idaho through the Snake River surface flow, with around 7.9 million acre-feet per annum exiting the Snake at King Hill.

In the irrigation season, the majority of the Snake’s volumetric flow upstream from Twin Falls is diverted for agricultural irrigation. Before irrigation commenced around 1900, two-thirds of the groundwater recharge to the eastern Snake River Plain was attributed to drainage basins tributary to the plain. However, by 1980, two-thirds of the groundwater recharge came from percolation of excess surface water diverted for irrigation, twenty percent came from tributary drainage basins, and about 13 perecent from precipitation on the plain.

A remarkable occurrence is found in the headwaters reach, where Two Ocean Creek actually splits at the Continental Divide in a relatively level marshy area; a pond is formed which simultaneously discharges to Atlantic Creek that flows east and into Pacific Creek that eventually reaches the Snake and hence the Pacific Ocean.

Water quality

Some of the principal water quality issues of the Snake River derive from agricultural runoff, including sedimentation, nitrate, phosphate, herbicide and pesticide substances. For example, in the Snake River plain of southern Idaho and eastern Oregon, more than three million acres of agricultural lands are irrigated, resulting in annual sediment loss of ten to 100 megagrams of sediment loss per hectare, due to the erodible silty soils.

Nitrates in the Upper Snake Basin are 70 to 80 percent attributable to agricultural return flow, via initial infiltration to groundwater. Greatest impacts to nitrate concentrations are from rill-irrigated row crops, as distinguished from drip or sprinkler type irrigation; correstpondingly sediment loads are much higher from rill-irrigation.

Aquatic biota

The endemic Cottus leiopomus. found in the upper Snake River. A number of [[fish] species] having very limited distributions are found in the Snake River Basin. For example, the Snake River sucker (Chasmistes muriei), is known only to a restricted reach of the Snake River below Lake Jackson, Wyoming; however, this fish is deemed to have become extinct by the year 1986. The endemic Wood River sculpin (Cottus leiopomus) occurs only in the Wood River and in a section of the Snake River near the Wood River confluence.

The endemic Cottus leiopomus. found in the upper Snake River. A number of [[fish] species] having very limited distributions are found in the Snake River Basin. For example, the Snake River sucker (Chasmistes muriei), is known only to a restricted reach of the Snake River below Lake Jackson, Wyoming; however, this fish is deemed to have become extinct by the year 1986. The endemic Wood River sculpin (Cottus leiopomus) occurs only in the Wood River and in a section of the Snake River near the Wood River confluence.

Shoshone Falls is thought to have formed in the time period 60,000 to 30,000 years before present. These falls presently form an absolute barrier to fish migration; moreover, the Shoshone Falls have formed a biological migration barrier for sufficiently long that only about 35 percent of the fish fauna above these falls with fish taxa of the lower Snake.

Early 1890s surveys from the upper Snake basin indicate the following historically abundant fish species: Utah sucker (Catostomus ardens), silver-sided minnow (leuciscus hydrophlox), longnose dace (Rhinichthys dulcis) and Utah chub (Gila atraria).

Terrestrial ecosytems

The Snake River traverses a number of ecoregions, chiefly:

Source: World Wildlife Fund

- Snake-Columbia scrub steppe - An endemic forb on the sagebrush steppe of the Snake River Plain is Lepidium papilliferum, a rare ephemeral species that is found in Lepidium (slickspot) microhabitats, and is threatened by overgrazing and trampling by domesticated livestock.

- Palouse grasslands - have been mostly destroyed (Habitat destruction) and degraded by overgrazing and by historic [[agricultural] land] conversion. The Palouse historically resembled the mixed-grass vegetation of the central grasslands, except for the absence of short grasses. Such species as Agropyron spicatum, Festuca idahoensis, and Elymus condensatus, and the associated species Poa scabrella, Koeleria cristata, Elymus sitanion, Stipa comata, and Agropyron smithii originally dominated the Palouse prairie grassland.

- Blue Mountains forests

- North Central Rockies forests - have a number of notablepopulations of large carnivores, including wolves (Canis lupus), grizzly bears (Ursus arctos), and wolverines (Gulo luscus). There are also populations of rare woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus ssp. caribou), the only caribou to live in areas of deep snow. Other wildlife include: black bear (Ursus americanus), mountain goat (Oreamnos americanus), grouse (Dendragapus spp.), waterfowl, black and white-tailed deer (Odocoileus hemionus and O. virginianus), and moose (Alces alces). In the southeast, marten (Martes ameriana) and bobcat (Lynx rufus) occur.

- South Central Rockies forests - have considerable intact habitat units including much of Yellowstone National Park, Grand Tetons, Frank Church Wilderness, central Idaho; Lemhi and Lost River Ranges, eastern Idaho; the Beaverhead, southwestern Montana;Anaconda-Pintler, southwestern Montana; Pioneer, southwestern Montana; Tobacco Root, southwestern Montana; Snowcrest, southwestern Montana; Centennial, southwestern Montana; and the Madison Ranges, southwestern Montana.

- Montana Valley and Foothill grasslands

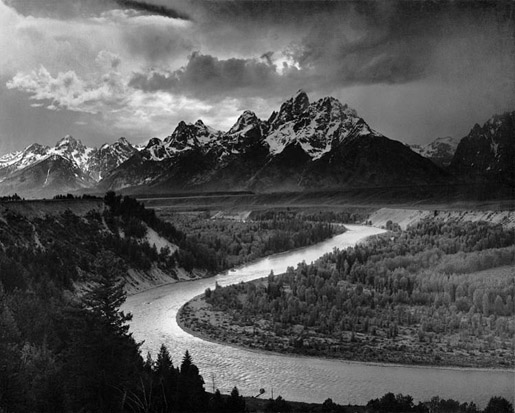

Looking south along the Snake with Tetons in background. @ Ansel Adams 1942

Looking south along the Snake with Tetons in background. @ Ansel Adams 1942

History

Early explorers and fur traders recorded two main prehistoric centers on the Snake river Plain in the early 1800s: the vicinity of Camas Prairie, and along the lower reaches of the Weiser and Payette rivers. These sites functioned as elements of a continental network, where commodities, manufactured goods, and environmental information were exchanged. They also served as a locus for dancing, gambling, tribal intermarriage and other social activities.

The Weiser sites were active as early as 2500 years BC, featuring obsidian trading along a Blue Mountain north-south trading axis stretching from Timber Butte in southeast Idaho north to the Clearwater River and even to the Pacific Ocean, via the Columbia Plateau, while Ollivella shell beads were also traded.

The Fremont Culture in southern Idaho is evinced by diagnostic artifacts, such as pottery, basketry and arrow-points. Shoshone Ware was found to be too broad a pottery type for the Snake River Plain here. Instead Southern Idaho Plain pottery has become recognized here to denote a finely made pottery, distinct from the classic thick-walled, flat-bottomed vessels usually called Shoshone Ware.

Satellite imagery of lower Snake River. @ NASA 1994

Satellite imagery of lower Snake River. @ NASA 1994

The Midvale Complex was first defined based on archaeological digs conducted at a sites near Midvale. The sites display a suite of activities including basalt quarrying for stone tool production, hunting, and root and seed processing. The Midvale Complex assemblage contains Bitterroot large side-notched arrow-points, Cascade arrow-points, leaf-shaped arrow-points, scrapers, choppers, edge-ground cobbles, elongate scrapers, and a gamut of unifacial and bifacial blanks or roughouts. Manos, pestles, milling stones, mortars, gravers, drills and pitted pebbles were also found, dating to 2500 BC to the time of Christ.

The corresponding assemblage has been documented at a host of sites throughout east Oregon and southwest Idaho. The distribution of the Midvale Complex includes most of the Blue Mountains region in eastern Oregon, Hells Canyon along the Idaho-Oregon border and much of southeast Idaho. The temporal span of this complex appears focused between 2500 to 500 years BC. The Midvale Complex has been linked to the Western Idaho Archaic Burial Complex found in southeastern Idaho. The Midvale Complex demarcates the convergence, by 2500 BC, of a subsistence lifestyle focused on regional trading. Its attributes are the cotemporaneous appearance of sizable pithouses, an array of highly stylized point types, diversification of ground stone tools, and burial grounds containing elaborate interments with rich burial furniture, a pattern noted for much of the Columbia Plateau. This complex is associated not only with enhanced residential sedentism and intensified exploitation of root-crops and salmon.

The explorer David Thompson was the first to note the Native American appellation for the Snake River as the Shawpatin as he arrived at the discharge location to the Columbia River in the year 1800.

References

- Robin A. Abell. 2000. Freshwater ecoregions of North America: a conservation assessment. books.google.com World Wildlife Fund (U.S.) 319 pages

- Gregory J.Fuhrer & Henry M.Johnson. 2000. Water Quality in the Yakima River Basin, Washington, 1999–2000. U.S.Geological Survey. Google eBook

- Idaho Water Resources Research Institute at Idaho Falls.Snake River Tributary Basins. University of Idaho, Idaho Falls.

- J.C.Kammerer. 1990. Largest Rivers in the United States. U.S.Geological Survey Government Printing Office. Washington DC

- Mark D.Lovell and Gary S.Johnson. 1999, Assessment of Needs and Approaches for Evaluating Ground Water and Surface Water Interactions for Hydrologic Units in the Snake River Basin. Idaho Water Resources Research Institute, University of Idaho, Moscow, Idaho

- Daniel S. Meatte. 1990. Prehistory of the Western Snake River Basin. Idaho Museum of Natural History. Abe Books. 107 pages

- Susan E.Meyer, Dana Quinney & Jay Weaver. 2005. A life history study of the Snake River plains endemic Lepidium papilliferum (Brassicaceae) Western North American Naturalist, Vol 65, No 1

- William F.Ritter & Adel Shirmohammadi. 2001. Agricultural nonpoint source pollution: watershed management and hydrology. 342 pages Google eBook

- Sarah V. Thomas & Claudia Copeland. 2008. Water pollution issues and developments. 280 pages Google eBook

- U.S.Fish Commission. 1893. Bulletin of the United States Fish Commission: Volume 11 United States. Google eBook