Fire in America

Lead Author: Stephen Pyne (other articles)

Content Partners: National Humanities Center (other articles) and TeacherServe (other articles)

Article Topics: Environmental history and Energy (Energy)

This article has been reviewed and approved by the following Topic Editor: Brian Black (other articles)

EDITOR'S NOTE: This entry was originally published as "History with Fire in Its Eye: An Introduction to Fire in America" in the series "Nature Transformed: The Environment in American History," developed by the National Humanities Center and TeacherServe. Citations should be based on the original essay.

Contents

Introduction

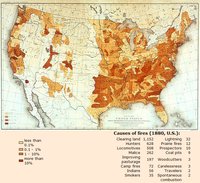

For the 1880 census, Charles Sargent mapped forest fires. wildfires were nearly everywhere, some places more vigorously than others. The amount of burning was, by today's standards, staggering. A developing nation, still primarily agricultural (Fire in America), the United States had a fire-flushed landscape not unlike those of Brazil and Indonesia in more recent decades. While lightning accounted for some ignition, and steam power (notably locomotives) for a growing fraction, the principal sources of fire were people—people burning for hunting, for traditional foraging, for land clearing, for clearing field fallow, for pasturage, for the ecological equivalent of housecleaning. And of course, there was a significant amount of sheer fire littering. Where spark met large caches of combustibles (as around logged sites), horrific fires, implacable as hurricanes, broke out. The idea that one might abolish fire seemed quixotic, in fact, dangerous. Without fire most lands were uninhabitable. Free-burning fires came and went with the seasons, as unstoppable as the movement of the sun across the heavens. Right-thinking conservationists, as good Progressives, argued for government intervention to stop them.

By the end of the 20th century, that scene had changed almost beyond recognition. Everywhere fire's domain was shrinking. Flame had vanished from houses and fields. Its primary habitats were the public lands of the West and those still-rural scenes of the forested South.

The problem with fires became one of maldistribution—too much of the wrong kind of fire, not enough of the right kind. Most fires burned as wildfires, set by lightning, accident, or arson. Many lands suffered from a fire famine, the shock of having a process to which they had long adjusted abruptly removed. On many sites, natural fuels had ratcheted up to levels against which fire suppression stood helpless. Government fire agencies sought to reinstate fire, often at considerable cost and risk, even in the face of public skepticism.

Between 1994 and 2000 the magnitude of the crisis became undeniable. In July 1994 a wildfire, kindled by lightning, overran a fire crew on Storm King Mountain in Colorado and killed fifteen crew members. The fatalities prompted not merely the usual review panels and reports but a profound soul-searching by the federal agencies about what justified putting those lives at risk. A revised federal policy emerged in December 1995. The alternative to fire control, it appeared, was controlled burning. This reflected common wisdom, accrued over the last thirty years.

In April 2000, however, the National Park Service set and lost two burns, the Outlet Fire on the North Rim of the Grand Canyon in Arizona and the Cerro Grande Fire at Bandelier National Monument in New Mexico. The first forced the evacuation of the North Rim and only ceased its run when it breached the canyon's rim. The second scoured the town of Los Alamos like the cutbank of a river. The agencies ordered a standdown from prescribed burning for a month and the Secretary of the Interior placed the Park Service program under a moratorium.

In truth, the 2000 fire season proved dismal for federal fire agencies, with burned area from wildfires reaching fifty-year highs, prescribed fires escaping, and suppression costs climbing to a stratospheric $1.3 billion. The two options for "managing" fire—fighting them and lighting them—had both failed, spectacularly. Fire suppression alone could not indefinitely contain fire. Yet prescribed fire was not ecological pixie dust that, sprinkled over degraded lands, could render them magically whole. More than starting and stopping ignition and shoving biomass around, the reintroduction of fire was akin to reintroducing a lost species. Fire needed a habitat. A National Fire Plan, authorized in late 2000, sought to begin reforms. Forest fuel reduction has been pinpointed as a national priority to minimize extent of future wildfire destruction.

The Humanities of Fire

We hold a species monopoly over fire. With fire we claim a unique ecological niche: this is what we do that no other creature does. Our possession is so fundamental to our understanding of the world that we cannot imagine a world without fire in our hands. Or to restate that point in more evolutionary terms, we cannot imagine another creature possessing it.

Yet while humans come genetically equipped to manipulate fire, we do not come programmed in its use. We apply and withhold it according to social institutions, cultural norms, perceptions of how we see ourselves in nature. Different people have created distinctive fire regimes, as they have distinctive literatures and architectures. In this way fire became both natural and cultural. If fire measures our ecological agency, so how we choose to apply and withhold it testifies to our understanding of that agency and the values, choices, and means by which we act. Fire enters humanity's moral universe, and thus into the scholarly realm of the humanities.

Consider, for example, Sargent's map, a complicated cartography. It records geographic conditions that make fire more plausible in some places than in others (the Northeast, for example, lacks a distinctive fire season; the Southwest experiences one annually). The map includes fires kindled from many sources. Lightning ignited some of them. But mostly people did, not simply out of perversity or recklessness but because fire is a profoundly interactive technology, and very few land-use practices happen without its catalytic presence somewhere in the web of causation.

It remains a map, not an image. Interpretation demands some understanding of fire behavior and fire ecology, and some understanding of how people use fire, because we compete with nature for fire control over the landscape and we compete with one another. Often rival fires clash. People rarely burn exactly as nature does, and what one group considers a controlled burn another might condemn as a wildfire. Interpreting the map thus requires some understanding of human history and how people have expressed their relationship to the natural world.

The Long Burn

A thumbnail history of fire would go like this. More than 400 million years ago the atmosphere had enough oxygen, the lands enough plant matter, and skies enough lightning for them to converge and create combustion. Fire has thrived on Earth ever since. It does so, however, in patterns called regimes, and these regimes are best understood as reflecting rhythms of wetting and drying. A place must be wet enough to grow combustible plants, and dry enough to ready them for burning. Some places experience this rhythm annually, some on longer scales of drought and deluge, some not at all. Individual fires are to fire regimes as individual storms are to climate. Still, biomass does not spontaneously combust; lightning must connect for ignition to result.

This narrative changed with early humans. Homo erectus could apparently maintain fire, and Homo sapiens make it, more or less at will. The Earth found a fire broker to link fuel with flame. Places that had the potential for fire but lacked regular ignition now had it. The outcome could be extraordinary, as, for example, with Madagascar and Australia, where change occurred on a continental scale.

Humanity found itself with a species monopoly that granted extraordinary power, but it would have to exercise that power according to social norms, values, perceptions, and institutions. Different people have created distinctive fire regimes, just as they have distinctive literatures and architecture. Thus fire became both natural and cultural, fit for analysis by both the natural sciences and the humanities. It became an agent of human change and an index of that change.

But immense limitations continued on humanity's firepower. Many places remained immune to ignition because they lacked the proper amount of dry fuel. The solution was to make fuel—cutting, burning, growing, stacking—which is, for fire history, the meaning of agriculture. Outside of floodplains, agriculture relied on a cycle of burning. In some cases, the farm moved through the landscape (as with classic slash-and-burn) or the landscape, in effect, revolved through a fixed plot of land (rotating fields). The practice of fallowing ensured that there would be sufficient fuel at the appropriate time. The fallowed land was not burned to remove its waste, but was grown in order to be burned. Thus agriculture expanded enormously the range and regimes of fire—bringing it to where it would not naturally have existed, reshaping its patterns into the discipline of fields and pastures.

Even so, anthropogenic fire could only burn what people or nature could produce. It remained within broad cycles of living biomass, the ancient rhythms of growth and decay. One could not take out more than one put back in.

This restriction lifted, however, when people reached in to the geological past and began exploiting fossil biomass—the petroleum, coal, and natural gas that had lain buried for eons. Suddenly fire—controlled combustion in the hands of people—could burn outside its ancient ecological constraints. It could burn day and night, winter and summer, without regard to the living world. It could burn within special habitats like combustion chambers. There is fuel enough to power machines for hundreds of years. For fire history, these events define industrialization.

Industrial fire is remaking every conceivable landscape, just as aboriginal fire and agriculture fire had before it. The environmental consequences have been extraordinary because the process is both adding a new and gigantic form of combustion and removing older forms. Both trends matter because fire can be just as ecologically powerful removed as applied. Biotas adapt to fire regimes just as they do to patterns of rainfall. More rain, less rain, a change in rainfall seasons—these can stress ecosystems. So it is with fire. Industrial societies have remade some landscapes by charging them with the flow of industrial combustion and remade others by removing older practices of open burning.

The human manipulation of fire has been complex. In some ways it resembles a simple tool. Flame sits at the end of a torch like an axe-head at the end of a handle. In other ways, it better approximates a process of domestication. People must tend a fire—birth it, feed it, propagate it, train it, as they would a sheep dog or milch cow. The tamed fire sustains, and is sustained by, a larger domesticated landscape. Yet, again, anthropogenic fire resembles a captive ecological process, something that people can start and stop and shape but which behaves largely as its quasi-wild context allows it to freely burn. Managing such fires is akin to training a grizzly bear to dance.

Industrialization has affected these variants of controlled fire differently. It is relatively simple to substitute one fire tool for another—to replace candles with light bulbs, and hearths with electric ovens. It is less easy to substitute for the domesticated flame on the landscape. Field fires behave according to the combustibles that feed them, and they do their ecological work according to their setting. Substituting for them is like substituting a tractor for a plow horse, and hence for the fields that grow the fodder for the horse and the barn that houses it, and so on. The exchange ripples beyond a simple replacement of one mechanical tool for another. Yet industrial fire is pushing such transformations through. Most spectacularly, it is eliminating the need for fallowing. Fire was a biotic catalyst that made agriculture possible beyond floodplains. But fire requires fuel, and fallow—the rank growth that flourished on abandoned fields—was the fuel that made fire possible and helped discipline it into the rhythms of farming and herding. Industrial agriculture, however, appeals to fossil fallow—fossil biomass that powers tractors, supplies artificial fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides, and overall finds replacements for the fertilizing and fumigation previously done by open fire. There is, however, no known surrogate for fire as an ecological process.

Fire at the Millennium

A fire map of the United States today would be a palimpsest of the three great fires of Earth:

- natural fire, primarily caused by lightning

- anthropogenic fire, human-made fire practices that rely on living biomass, such as burning trees to clear land and stimulate pasture

- industrial fire, those stoked by fossil fuels such as coal and petroleum, i.e., nonliving biomass.

- arson and fire emanating from homeless encampments in forests

Compared to the past, such a map would show a massive loss of open flame. Where people live most densely—in cities—fire is rare and considered intrinsically dangerous. Elsewhere, it exists largely as wildfire, and that on public wildlands. What has most vanished is the ancient realm of controlled burning. It flourishes most vigorously today in places of aggressive land clearing. Several problems dominate the contemporary discourse about American fire:

- The role of fire in wilderness and nature reserves. Many such sites (especially those in the American West) experience regular burning from lightning. These are natural events and should, it would seem, be tolerated, even encouraged. But how to reinstate "natural" fire has proved knotty, costly, and ironic. It has happened in a few places, notably along the Sierra Nevada. The scheme underwent a colossal collapse during the Yellowstone National Park fires of 1988. What to do with such fires is very much a matter of cultural choice.

- The increased mixing of wildlands and cities. In many places urban fragments are flung into quasi-wild landscapes that are prone to burn. In other places abandoned agricultural lands are regrowing to woody thickets, again abutting houses. A gross description is that the once-rural landscape is being recolonized by urban (or suburban or exurban) peoples according to values and an economy they derive from elsewhere. If fire is at all possible, this mixture has proved volatile and unstable. Almost annually more and more houses fall to flame. This is a dumb problem to have because technical solutions exist such as zoning, landscaping, and incombustible roofs.

Controlled burn, Florida, 2001. (Source: © South Florida Water Management District)

Controlled burn, Florida, 2001. (Source: © South Florida Water Management District) - The relative merits of fire control and controlled fire. As a solitary technique, fire suppression has failed, so the argument has developed that we must retool to start fires instead. We must light fires because we can no longer assume we can fight them. But this misstates the issue. The choice is not one or the other, but the proper proportions of each as tested site by site. Nature does not set those proportions, people do. And we do it according to a confusing welter of values, choices, accidents, institutions, knowledge, perceptions, and misinformation for which the humanities are aptly equipped to explain and advise. The reintroduction of fire will demand suitable habitats, which is to say, the issues are not simply about kindling fires but about land use, and about how we see ourselves in relation to particular places.

- The status of burning in a context of global change. Like human populations undergoing industrialization, the population of fires tends to swell up alarmingly as new combustion sources appear and old practices persist. Eventually the population shrinks as the old ways collapse. But how to reconcile the continued need for some open fire within a planet temporarily overcharged with combustion is a tough call. It will force us to choose from among environmental values, for example, between biodiversity and carbon sequestration. Allowing forests to overgrow into woody tangles can stockpile carbon, but will likely bury the biotic variety of the landscape under a pavement of needles and woody litter. Conversely, breaking open such groves may enhance biodiversity but at a cost of liberated carbon.