Federal environmental review of oil and gas activities in the Gulf of Mexico: environmental consultations, permits, and authorizations

Editor's Note: This article is excerpted directly from National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and Offshore Drilling, "Federal Environmental Review of Oil and Gas Activities in the Gulf of Mexico: Environmental Consultations, Permits, and Authorizations," Draft, Staff Working Paper No. 21. It has been edited only to conform to the Encyclopedia's style guidelines.

This staff working paper summarizes many of the ocean and coastal environmental laws that are applicable to oil and gas activities on the [Continental Shelf].1 It discusses the environmental review, interagency consultation, and permitting requirements of these laws, as well as how the federal agencies charged with their administration applied those requirements in the Gulf of Mexico in advance of the Deepwater Horizon incident. Finally, the paper concludes with an appraisal of relevant issues related to the environmental review of oil and gas activities for consideration by the Commissioners. Appendix I of the paper provides additional background and analysis regarding Oil Spill Response Plans and Oil Spill Risk Analyses, as well as discussing their connection to the offshore oil and gas (A brief history of offshore oil drilling) environmental review process.

Contents

- 1 Background

- 2 Major Federal Environmental Laws Applying to Oil and Gas Activities in the Gulf of Mexico

- 3 Additional Areas for Commission Consideration

- 4 Appendix I: Oil Spill Response Plans and Oil Spill Risk Analyses

- 5 End Notes

Background

Credit: Idaho.gov Credit: Idaho.gov

|

The Deepwater Horizon incident has focused a great deal of attention on the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) process for reviewing [Continental Shelf] oil and gas activities. However, there are a number of other important ocean and coastal environmental laws applicable to offshore oil and gas (A brief history of offshore oil drilling) activities that include their own environmental review and interagency consultation requirements. In certain respects, these laws can be more demanding than NEPA’s requirements. NEPA’s mandate is essentially procedural, requiring federal agencies to consider the adverse environmental impacts of their actions without mandating that they not cause those impacts. In contrast, many of the other environmental laws go further, requiring federal agencies to state their rationale for not taking more environmentally protective measures, or imposing limits on the extent to which the activities under consideration may harm the environment. The resulting statutes provide for a layer of detailed environmental review beyond NEPA, generally resulting in recommendations to decrease environmental impacts on individual species or ecosystems. A diverse set of issues are covered by these laws, including marine mammals, endangered species, marine fish and their habitats, marine sanctuaries, the coastal zone, and water quality. Environmental reviews conducted under these statutes are important to understanding and minimizing the environmental impacts of offshore oil and gas (A brief history of offshore oil drilling) activities.

The following environmental statutes and associated consultations, permits, or authorizations for oil and gas activities in the Gulf of Mexico are examined in this paper: the Magnuson Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act; Endangered Species Act; Marine Mammal Protection Act; National Marine Sanctuaries Act; Coastal Zone Management Act; and the Clean Water Act.

Major Federal Environmental Laws Applying to Oil and Gas Activities in the Gulf of Mexico

Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act

Bringing the net aboard during shrimp trawling operations in the Gulf of Mexico (Aug. 1968). Credit: NOAA Bringing the net aboard during shrimp trawling operations in the Gulf of Mexico (Aug. 1968). Credit: NOAA

|

As its title suggests, the Fishery Conservation and Management Act of 1976 (known as the Magnuson-Stevens Act) is focused on the conservation and management of marine fishery resources and their habitat in federal waters.2 In 1996, amendments to the Act added a mandate to describe, identify, and ensure the conservation and enhancement of “essential fish habitat.”3 Essential fish habitat is defined by the amended Act as those waters and substrate necessary for fish spawning, breeding, feeding, or growth to maturity.4 The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries Service is the federal agency responsible for administering the Magnuson-Stevens Act. NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) and the Regional Fishery Management Councils established by the Act have designated essential fish habitat for more than 1,000 species to date.5 These species include marine finfish, mollusks, corals, and crustaceans. In the aggregate, these distinct essential fish habitat areas cover much of the waters of the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone – as a result, NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) and the Regional Councils have further designated “habitat areas of particular concern” within the broader essential fish habitat. Habitat areas of particular concern are high-priority areas for conservation, management, or research, due to the areas being rare, sensitive, particularly susceptible to human-induced degradation, or important to ecosystem function.6 NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) and the Regional Fishery Management Councils have identified approximately 100 habitat areas of particular concern.7

The Magnuson-Stevens Act is relevant to oil and gas activities on the[Continental Shelf] because it requires federal agencies to consult with NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) on any action authorized, funded, or undertaken that may adversely affect identified essential fish habitat. NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) has defined “adverse effect” in regulation to mean any action that reduces the quality or quantity of essential fish habitat.8 This can include direct or indirect physical, chemical, or biological alterations of waters or substrate, as well as loss or injury of benthic organisms, prey species and their habitat, and other ecosystem components. As part of the consultation, NOAA’s essential fish habitat regulations call upon action agencies to prepare an “essential fish habitat assessment” (EFH Assessment) that includes, among other things: a description of the proposed action; an analysis of the potential adverse effects of the action on essential fish habitat and managed species; the action agency’s conclusions regarding the effects of the action on essential fish habitat; and proposed mitigation measures, if applicable.9 The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation and Enforcement (BOEMRE), the successor agency to the Minerals Management Service (MMS), is responsible for consulting with NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) and preparing EFH Assessments for its actions related to oil and gas activities on the [Continental Shelf].10

Based on its evaluation of the EFH Assessment and associated NEPA analyses, NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) will conduct an essential fish habitat consultation (EFH consultation) and provide BOEMRE with Conservation Recommendations to avoid, minimize, mitigate, or otherwise offset the adverse effects of BOEMRE’s actions.11 BOEMRE must respond in writing to NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States)’s Conservation Recommendations by either accepting the recommendations, or by explaining why they are not accepting them.12 If BOEMRE disagrees with NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States)’s recommendations, BOEMRE must explain its reasons for not following them.13 In addition, BOEMRE must describe the measures they are proposing to implement for avoiding, mitigating, or offsetting the impact of the proposed activity on essential fish habitat.14

[Continental Shelf] oil and gas activities that are most likely to trigger the Magnuson- Stevens Act’s essential fish habitat assessment and consultation requirements are those that disturb the seafloor, discharge materials into the ocean, degrade coastal or nearshore habitats, or intake large volumes of seawater.15 In addition to reviewing potential impacts to fisheries (Fisheries and aquaculture) habitat, the consultation also considers the direct effects of the action on marine and anadromous fish species and their prey. In 1999, the Minerals Management Service (MMS) prepared a programmatic EFH Assessment,16 and NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) engaged in a programmatic EFH consultation, each of which addressed a number of proposed oil and gas activities in the Gulf of Mexico, including pipeline rights-of-way, planning for exploration and production, and platform removal.17

The 1999 MMS programmatic EFH Assessment relied heavily on analyses contained in MMS NEPA documents prepared for Central and Western Gulf of Mexico lease sales. It found a number of major impact-producing factors that could affect essential fish habitat,18 including blowouts and petroleum spills. In its discussion of “Fisheries Impacts” in the analysis section of the EFH Assessment, MMS noted that oil spills could negatively impact marine fish through the ingestion of oil or oiled prey, uptake of dissolved petroleum products through the gills, death of eggs, and decreased survival of larvae. However, discussion in the section indicated that there was a limited risk posed by oil spills to commercial marine fisheries due to the following factors: (1) the effects and damage from an oil spill are restricted by time and location; (2) lack of evidence that commercial fisheries in the Gulf had been adversely affected on a regional population level by oil spills or chronic oiling; and (3) observations that free-swimming fish were rarely at risk from oil spills.19 According to the EFH Assessment:

Fish swim away from spilled oil, and this behavior explains why there has never been a commercially important fish-kill on record following an oil spill. Large numbers of fish eggs and larvae have been killed by oil spills. However, fish over-produce eggs on an enormous scale and the overwhelming majority of them die at an early stage, generally as food for predators.20

The EFH Assessment stated that activities like “seismic surveys, subsurface blowouts, pipeline trenching, and OCS Continental Shelf discharge of drilling muds [fluids] and produced water will cause negligible impacts and not deleteriously affect Central and Western [[Gulf] commercial fisheries].”21 In contrast, it stated that operations such as “production platform emplacement, underwater OCS impediments, explosive platform removal, oil spills, and activities that result in coastal environmental degradation will cause greater impacts” on commercial fisheries. The overall conclusion by MMS was that all the oil and gas activities covered under the EFH Assessment would result in less than a 1% decrease in commercial fishery populations, essential fish habitat, and commercial fishing.22 It also determined that it would require less than six months for fishing activity and one generation for fishery resources to recover from 99% of the impacts during a single action period. To address the threat to essential fish habitat and marine fishery resources from oil spills, MMS proposed that industry Oil Spill Response Plans serve as a mitigation measure. These plans were required by MMS for all owners or operators of oil handling, storage, or transportation facilities that are located seaward of the coast.23 In addition to this mitigation measure, MMS proposed another four measures in the EFH Assessment that were not directly related to oil spills.24

NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) noted concerns with portions of the EFH Assessment related to oil spill impacts in the EFH consultation.25 However, when supplemented with information contained in the MMS NEPA analysis, NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) found that the EFH Assessment was an acceptable overall evaluation of potential adverse impacts. Based on its analysis, NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) accepted four of the MMS-proposed mitigation measures, and added six additional Conservation Recommendations.26 MMS agreed to adopt the additional Conservation Recommendations and initiated measures, including Notices to Lessees, to implement them.

Since 1999, NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) has updated the programmatic essential fish habitat consultation three times: in 2006, 2007, and in 2008.27 The updates mostly dealt with revised planning area boundaries, and did not change the Conservation Recommendations contained in the 1999 EFH consultation. Although the 1999 programmatic EFH Assessment and consultation remain in place, MMS integrated future essential fish habitat assessments for oil and gas activities in the Gulf of Mexico into NEPA documents (Environmental Impact Statements and Environmental Assessments) for those activities.28 For example, the Final Environmental Impact Statement for Gulf of Mexico Lease Sales 2007-201229 contained an essential fish habitat assessment for eleven different lease sales in theGulf of Mexico.30 The acreage analyzed in this NEPA document and the associated essential fish habitat assessment covered 58.7 million acres for the Central Planning Area sale area, and 28.7 million acres for the Western Planning Area.31

Magnuson-Stevens Act Issues for Commission Consideration

A line of shrimping boats acting as Vessels of Opportunity (VOOs) return to the port of Bayou La Batre after a shift change on Saturday June 12, 2010. Credit: Washington Department of Ecology A line of shrimping boats acting as Vessels of Opportunity (VOOs) return to the port of Bayou La Batre after a shift change on Saturday June 12, 2010. Credit: Washington Department of Ecology

|

NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) has recognized the need to update the 1999 programmatic essential fish habitat consultation in light of the oil spill (Deepwater Horizon oil spill ). On September 24, 2010, NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) formally requested that BOEMRE conduct a new essential fish habitat assessment and reinitiate consultation under the Magnuson-Stevens Act.32 This would provide an opportunity to re-evaluate the previous assumptions related to oil-spill risk and impacts to essential fish habitat. This consultation will again be conducted on a programmatic basis, which allows NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) to broadly evaluate the cumulative impacts of oil and gas operations across the Gulf of Mexico planning areas. However, NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) may also want to consider whether the broad consultation should be supplemented with additional analyses on a smaller geographic scale that would allow for a finer analysis of habitat impacts during the later stages of the BOEMRE [Continental Shelf] oil and gas leasing, exploration and development process (such as during approval for exploration or development and production plans).

One deficiency highlighted by the Deepwater Horizon incident is reliance by the government on industry Oil Spill Response Plans to address the threat of oil spills on essential fish habitat. These plans focus on what happens once an oil spill occurs, rather than steps to prevent the spill from occurring. Although they might be able to assist in planning a more efficient or effective oil-spill response, they may not work as a stand-alone measure for preventing damage to fishery resources (Fisheries and aquaculture) and habitat from oil spills. NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) and BOEMRE may need to consider alternatives that expand the Conservation Recommendations to include measures for oil-spill prevention and response.

In addition to the question of whether Oil Spill Response Plans are the correct tool to address oil-spill threats to essential fish habitat, the adequacy and content of those plans in the Gulf of Mexico has also been seriously questioned following the Deepwater Horizon incident. The Oil Spill Response Plans did not (and were not legally required to) undergo an interagency or public review process before approval by MMS. Although the content of the BP Oil Spill Response Plan appears to have met the requirements established by MMS, many of its sections lack the analysis and geographic specificity that would have made it a more meaningful tool for minimizing oil-spill impacts on living marine resources and essential fish habitat. Updating the plan requirements based on lessons learned from the BP oil spill, along with implementing a more thorough approval process that includes interagency review by the U.S. Coast Guard, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States), could be extremely helpful in improving the content and relevance of the plans. Commissioners may also want to consider options for making the plans more transparent to the general public by including a requirement for a public comment period before approval by BOEMRE, and the public posting of final Oil Spill Response Plans online.33

Endangered Species Act

Humpback whales are protected by the U.S. Marine Mammal Protection Act, but also are found outside of U.S. waters. Credit: NOAA Humpback whales are protected by the U.S. Marine Mammal Protection Act, but also are found outside of U.S. waters. Credit: NOAA

|

The [[Endangered Species Act] of 1973], which seeks to conserve threatened or endangered species, is another federal law applicable to oil and gas drilling activities on the [Continental Shelf]. The Act (Endangered Species Act, United States) is jointly implemented by NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) Fisheries Service and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Together, the two agencies have listed more than 1,900 species as endangered or threatened under the Endangered Species Act. NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) is responsible for 69 listed marine and anadromous species that include sea grass, corals, fish, turtles, and whales.

The Endangered Species Act is one of the nation’s most demanding environmental laws. Some of its provisions apply exclusively to federal agencies, while others apply to any activity with the potential to harm an endangered or threatened species, irrespective of the actor. The Act imposes absolute prohibitions, permitting limitations, environmental assessment mandates, and interagency consultation requirements.

One of the Act’s most sweeping restrictions makes it unlawful to “take” any endangered species (absent a permit that is available only in limited circumstances). The Act broadly defines “take” as “to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect, or to attempt to engage in any such conduct.”34 Through administrative regulation, the Act’s prohibition on takings has not only been extended to threatened species, but the definition of “harm” has been extended to include the modification of species habitat that physically injures or kills an individual member of a species.35 As a result, the Act makes activities unlawful that harm endangered or threatened species by causing a change in their habitat. The Act (Endangered Species Act, United States) also directs NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to identify endangered and threatened species and designate their critical habitat.36

Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act requires federal agencies to consult with NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to ensure that any action authorized, funded, or carried out is not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of endangered or threatened species, or result in the destruction or adverse modification of their designated critical habitat.37 Section 7 sets forth a series of consultation requirements with NOAA and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service designed to ensure compliance with this prohibition. If an action may affect a listed species, or either NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) or the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service advise that such a species might be in the area, then the federal agency must prepare a “Biological Assessment” that identifies any endangered or threatened species that might be adversely affected.38 If the Assessment concludes that there is potential for an adverse effect, then NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) or the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (depending on which agency is responsible for that species) must prepare a “Biological Opinion.”39 The Biological Opinion describes the extent of the adverse effect, whether the proposed agency action will jeopardize the continued existence of endangered or threatened species, and whether the proposed agency action will adversely modify or destroy critical habitat.40

If NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) or the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service determine that either jeopardy of the species or adverse modification/destruction (Habitat destruction) of designated critical habitat will occur, they must suggest “reasonable and prudent alternatives” that will reduce the impact of the activity so it can occur without violating Section 7.41 The federal agency must implement these alternatives to avoid jeopardizing the species or adversely modifying/destroying its critical habitat. Absent an exemption from Section 7, if NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) or the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service concludes that there are no reasonable and prudent alternatives, then the federal agency is barred from taking its planned action.42 In this respect, the Endangered Species Act’s consultation requirement is far tougher than that provided by either NEPA or the Magnuson-Stevens Act – the result of consultation may be to prohibit the proposed federal agency action altogether.

Potential impacts from [Continental Shelf] oil and gas activities that are likely to trigger Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act include: disturbance or damage to critical habitat from construction of pipelines or placement of anchors and structures on the ocean floor; acoustic impacts from seismic surveys; strikes of listed sea turtles or marine mammals by vessels supporting oil and gas activities; discharge of toxic fluids or marine debris; and oil spills. NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) completed its most recent formal oil and gas consultation and Biological Opinion for the Gulf of Mexico in June 2007 for seven listed marine species (five species of sea turtle, Gulf sturgeon, and sperm whales).43 The consultation considered the effects of activities occurring under the Five-Year [Continental Shelf] Oil and Gas Leasing Program (2007-2012) in the Central and Western Planning Areas of the Gulf of Mexico. Specific activities analyzed included seismic surveys, platform construction activities, well drilling and development, pipeline installation, vessel traffic, helicopter use, and spilled oil. Effects were considered over the typical 40-year lifespan of all leases that would be granted during the 2007-2012 lease sale period. Potential effects included: vessel strikes; acoustic impacts; marine debris; habitat destruction; animal displacement; discharge of heavy metals; and degradation of water quality. NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) determined in the Biological Opinion that sea turtles and Gulf sturgeon were not likely to be adversely affected by most of these effects, but opted to conduct a more detailed analysis of the effects of vessel strikes on sea turtles, seismic activity on sperm whales, and the effects of oil spills on all listed species.

The NOAA analysis of potential oil-spill effects on listed species and their habitat was comprehensive. However, NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States)’s estimation of potential takes of endangered and threatened species from oil spills relied on MMS oil spill risk analysis modeling. With the benefit of hindsight, it is clear that the MMS risk analysis significantly underestimated the “rare event” spill scenario as releasing approximately 630,000 gallons of oil over the 40-year lifetime of the proposed leases in the Gulf of Mexico Central Planning Area, and up to 875,490 gallons of oil inthe Gulf of Mexico Western Planning Area.44 Based on these MMS oil spill estimates, it can be comfortably assumed that NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) subsequently underestimated the number of potential takes of endangered and threatened species by an oil spill like the Deepwater Horizon incident (estimated at a total of roughly 4.2 million barrels or 176 million gallons of oil released into the marine environment).

NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States)’s Biological Opinion concluded that the proposed oil and gas activities were not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of any sea turtle species, Gulf sturgeon, or sperm whales.45 The Biological Opinion also provided reasonable and prudent measures designed to reduce the risk of accidental vessel strike with sea turtles, as well as a series of conservation recommendations. These conservation recommendations focused on the need for: research on the cumulative effects of noise from oil and gas construction activities; proposed cooperative NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States)-MMS work on marine mammal observer programs; reduction of marine debris; and research on the impacts of oil and gas activities on protected species. Although NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) considered the impacts of oil spills on listed species as part of the Biological Opinion and jeopardy analysis, NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) did not authorize the take of any endangered or threatened species from oil spills due to the fact that spills are considered an unlawful activity. MMS implemented the terms and conditions of the Biological Opinion through three Notices to Lessees in 2007.46

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service completed its most recent formal oil and gas consultation and Biological Opinion for the Gulf of Mexicoin January 2003 for eight listed species (whooping crane, gulf sturgeon, brown pelican, Alabama beach mouse, Perdido Key beach mouse, Kemp’s ridley sea turtle, loggerhead sea turtle, and piping plover).47 The consultation considered the effects of activities occurring under lease sales in the Central and Western Gulf of Mexico from 2003 through 2007. Based on a review of the status of the species and their critical habitat, the environmental baseline for the action area, the effects of the proposed oil and gas lease sales, and an analysis of cumulative effects, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service determined that the proposed leasing, exploration, development, production, and abandonment activities were not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of listed species under their jurisdiction. A conservation recommendation was included in the consultation regarding the content of oil spill response plans and other hazardous emergency contingency plans. The recommendation requested a variety of items be incorporated into the plans, including: identification of critical habitat; oil spill trajectory models; implementation plans for protection of endangered and threatened species and their habitats in case of a spill; identification of sea turtle nesting sites and provisions for removal of eggs in case of a spill; and a request that MMS coordinate annually with the U.S. Coast Guard to ensure that the plans contained up-to-date information on sensitive areas for the species.

According to Department of Interior staff, this formal consultation was followed by an informal consultation in September 2007 on the 2007-2012 Five-Year [Continental Shelf] Oil and Gas Leasing Program. The informal consultation considered the impacts of proposed oil and gas activities on over 30 different species (including a variety of turtles, birds, manatee, and beach mice). It determined that the proposed oil and gas activities were not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of any endangered or threatened species, or result in the destruction or adverse modification of their critical habitat.

Endangered Species Act Issues for Commission Consideration

In light of the BP oil spill and its impacts on living marine resources, BOEMRE formally requested re-initiation of interagency consultation under the Endangered Species Act with both NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, on July 30, 2010.48 In its request, BOEMRE noted that the spill volumes and scenarios used in the analysis for both the NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) and U.S. Fish and Wildlife consultations needed to be readdressed given the occurrence of a “rare event” spill exceeding 420,000 gallons as referenced in the NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) biological opinion, and potential oil spill impacts on listed species and their critical habitat. NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) concurred with this request on September 24, 2010, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service concurred with the request on September 27, 2010.49 In NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States)’s response letter to BOEMRE, NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) highlighted concerns that the previous BOEMRE environmental impact statement did not estimate the size of a catastrophic spill, and NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) was instead required to rely on historical data and other assumptions to estimate the potential size and impacts of such a spill on listed species. NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) stated that it did not believe that the oil spill assumptions sufficiently addressed the potential risks of a spill the magnitude of the BP oil spill, or the associated risks to listed species and their habitats. NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) specifically requested that BOEMRE re-analyze the risk of oil spills and the potential impacts of oil and gas industry response activities on listed species and their habitats. NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) also requested that BOEMRE develop new oil-spill probabilities and modeling for different sized spills (including catastrophic spills). The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service also encouraged BOEMRE to conduct additional modeling to address the BP oil spill scenario and its potential effects on listed species and their designated critical habitat.

The Commissioners may want to reinforce the request that BOEMRE update and revise its oil spill risk analyses for the Gulf of Mexico and Alaska with information learned during the BP oil spill. It may be appropriate for BOEMRE to complete separate oil spill risk analyses for shallow water oil and gas activity and deepwater activity in the Gulf of Mexico. This information should be integrated into the estimates for takes of threatened and endangered species in an updated Biological Opinion. The Commissioners may also want to consider whether NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service should establish an internal expertise for conducting oil spill risk analyses, or opt for another method to independently review BOEMRE oil spill risk analyses.

Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA)

Bottlenose dolphins, including this mother and calf, often interact with fish species of commercial importance. Credit: NOAA Bottlenose dolphins, including this mother and calf, often interact with fish species of commercial importance. Credit: NOAA

|

The [[Marine Mammal Protection Act] of 1972] was enacted in response to concerns that significant declines in some species of marine mammals were caused by human activities.50 The Act established a national policy to prevent marine mammal species and population stocks from declining beyond the point where they ceased to be significant functioning elements of their ecosystems. It applies to all marine mammals, regardless of population stock health or size. The Act directly regulates human activities that threaten to harm marine mammals by making it generally illegal to “take” a marine mammal without prior authorization from NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) Fisheries Service or the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.51 “Take” under the Marine Mammal Protection Act means “to harass, hunt, capture, or kill, or attempt to harass, hunt, capture or kill any marine mammal.”52 “Harassment” is further defined by the Act as any act of pursuit, torment, or annoyance which (i) has the potential to injure a marine mammal or marine mammal stock in the wild; or (ii) has the potential to disturb a marine mammal or marine mammal stock in the wild by causing disruption of behavioral patterns, including, but not limited to, migration, breathing, nursing, breeding, feeding, or sheltering.53

Under the Act, NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service authorize the take of small numbers of marine mammals incidental to otherwise lawful activities (except commercial fishing), provided that the takings would have no more than a negligible impact on those marine mammal species, and would not have an unmitigable adverse impact on the availability of those species for subsistence uses.54 If any aspect of a proposed activity is expected to result in a take, the project applicant is required to obtain an incidental take authorization (either a Letter of Authorization or an Incidental Harassment Authorizations) in advance from NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) Fisheries Service or the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. When issued, these authorizations include mitigation, monitoring, and reporting requirements that must be followed by the applicant.55

There are 28 species of marine mammals in the Gulf of Mexico. Activities from [Continental Shelf] oil and gas activities that could result in potential takes of marine mammal and a need for an incidental take authorization include: activities related to the explosive removal of offshore structures,56 seismic exploration, construction, and drilling. There are currently no U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service authorizations for the take of marine mammals incidental to oil and gas operations in the Gulf of Mexico. However, NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) does have an active authorization for the incidental take of dolphins during oil and gas structure removal operations. NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) promulgated the Marine Mammal Protection Act Incidental Take Authorization regulations for these activities in 1995. The regulations were most recently re-issued for the Gulf of Mexico in 2008.57

In addition, based on Commission staff interviews and research, it appears that MMS applied to NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) for Marine Mammal Protection Act incidental take regulations for geological and geophysical exploration, or seismic surveys, in the Gulf of Mexico in 2002. The application was specific to the potential take of sperm whales. At that time, MMS was in the process of developing a Programmatic Environmental Assessment to support the action. Upon review, NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) found that the Environmental Assessment would not be sufficient for the regulations, and instead requested that a full Environmental Impact Statement be prepared. NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) also determined that the species covered by the regulations should be expanded beyond sperm whales. In 2004, NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) received a revised application from MMS that included dolphins, beaked whales, and Bryde’s whales. MMS later decided to make additional changes to the application, which was re-submitted to NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) in November 2010. To support the Marine Mammal Protection Act regulations, BOEMRE and NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) are working together as cooperating agencies in the preparation of a Draft Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement for Geological and Geophysical Exploration of Mineral and Energy Resources in the Gulf of Mexico.

Marine Mammal Protection Act Issues for Commission Consideration58

Although there has not been a complete lack of activity related to the Marine Mammal Protection Act authorizations for oil and gas seismic activity in the Gulf of Mexico, heavy NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) staff workloads (particularly a large number of U.S. Navy actions requiring Marine Mammal Protection Act authorizations) and a lengthy back-and-forth between NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) and MMS on applications and supporting documents appear to have contributed to the slow pace of progress. Commissioners may want to consider whether additional resources are warranted, given the fact that they would be extremely helpful to expediting and expanding the scope of Marine Mammal Protection Act permitting for oil and gas activities. Additional funding for marine mammal stock assessments would also serve to strengthen the science underlying the Marine Mammal Protection Act incidental take authorizations and their associated [[NEPA] documents].

National Marine Sanctuaries Act

Congress first enacted the [[National Marine Sanctuaries Act] in 1972], and has amended and reauthorized the Act on six subsequent occasions.59 The Act (Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act, United States) provides NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) with the authority to protect and manage the resources of significant marine areas of the United States. NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States)'s administration of the marine sanctuary program involves designation of national marine sanctuaries and adopting management practices to protect the conservation, recreational, ecological, educational, and aesthetic values of those areas.

The Sanctuaries Act and its implementing regulations regulate activities that might cause adverse impacts on Sanctuary resources. The Act also includes an interagency consultation requirement. Any federal agency that is taking an action either inside or outside the boundary of a Sanctuary that is “likely to destroy, cause the loss of, or injure any Sanctuary resource”60 is required to provide NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) with a written statement describing the action and its potential effect.61 If NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) finds that the federal action or permitted activity is likely to injure Sanctuary resources, the Secretary of Commerce will recommend alternatives to the proposed action.62 Those alternatives could include choosing a different location for the activity.63 If the action agency chooses not to follow the recommended alternatives, it must provide NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) with a written explanation. If Sanctuary resources are eventually destroyed, lost, or injured after a federal agency chooses not to follow NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States)’s alternatives, the federal agency is required to act to prevent further damage and to restore or replace the resources in a manner approved by NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States).64

There are two Sanctuaries in the Gulf of Mexico, both of which include unique reef ecosystems: Flower Garden Banks and Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuaries. [[Flower Garden Banks] National Marine Sanctuary] is approximately 42 square nautical miles in size and consists of three separate areas that are located approximately 70 to 115 miles off the coasts of Texas and Louisiana in the western Gulf of Mexico. The Banks contain the northernmost coral reefs in the continental United States. They sit on salt domes that rise to within 55 feet of the surface and serve as a regional reservoir of shallow water Caribbean reef fishes and invertebrates.65 The Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary is located in the far southeast corner of the Gulf of Mexico, encompassing 2,900 square nautical miles and stretching across the Florida Keys from the Gulf of Mexico to the Atlantic Ocean. The Florida Keys Sanctuary contains extensive offshore coral reefs (Coral reefs in Florida), fringing mangroves (Mangrove ecology), seagrass meadows, hard bottom regions, patch reefs, and bank reefs – a complex marine ecosystem that serves as the foundation for the commercial fishing and tourism based economies that are vital to south Florida.66

While each Sanctuary has its own unique set of regulations, there are some regulatory prohibitions relevant to oil and gas activities that are typical for many sanctuaries. For example, the following activities are generally not permitted: discharging material or other matter into the sanctuary; disturbance of, construction on, or alteration of the seabed; disturbance of cultural resources; and exploring for, developing, or producing oil, gas, or minerals (with a grandfather clause for preexisting operations). Oil and gas activities are not allowed within the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, and are only allowed in the [[Flower Garden Banks] National Marine Sanctuary] outside designated no-activity zones (which comprise most of the Sanctuary’s area). Currently, there is one preexisting oil and gas platform that is located within the boundaries of the Flower Garden Banks, but outside the no-activity zones. The [[Flower Garden Banks] National Marine Sanctuary] superintendent has reviewed proposals for oil and gas activities near the Sanctuary; for a number of the actions that were proposed in close proximity to Flower Garden Banks, NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) has conducted consultations pursuant to the Sanctuaries Act. These consultations consistently warned MMS about potential impacts to sanctuary resources and associated liability in the case of an accidental oil spill.

National Marine Sanctuary Act Issues for Commission Consideration

The BP oil spill highlighted the possibility that oil from a spill in the Central or Western Gulf of Mexico could be carried long distances to Flower Garden Banks or the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary via the Gulf of Mexico Loop Current or associated eddies. If this occurred, it could potentially damage Sanctuary resources both inside and outside the boundaries of the Sanctuaries. Commissioners may want to consider whether NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) should expand the geographic scope of its National Marine Sanctuary Act consultations for deepwater oil and gas activities that are proposed at a distance from the Sanctuaries, but which have the potential to impact Sanctuary resources should a large spill occur.

Coastal Zone Management Act

The [[Coastal Zone Management Act] of 1972] (CZMA) sets a national policy to encourage states to preserve, protect, develop, restore and enhance natural coastal resources.67 It also encourages coastal states to develop and implement comprehensive programs to manage and balance competing uses of and impacts to coastal resources. The state coastal management programs are developed pursuant to CZMA and NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) requirements, with input from federal agencies, local governments and the public. The programs are approved by NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States). The Act emphasizes the primacy of state decision-making regarding each state’s coastal zone. In addition, once NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) has approved a state’s coastal management program, a state also implements its program through the CZMA’s “federal consistency” provision. This provision requires activities proposed by a federal agency that have reasonably foreseeable effects on any land or water use, or natural resource of the state’s coastal zone to be consistent to the maximum extent practicable with the enforceable policies of the state’s federally approved coastal management program. Non-federal applicants for federal licenses or permits must also be fully consistent with the enforceable policies of the state’s federally approved coastal management program.68 If a state coastal management program objects to a non-federal applicant’s federal license or permit activity, the non-federal applicant for the activity may appeal to the Secretary of Commerce. If the Secretary sustains a state’s objection, the federal agency may not authorize the activity; if the Secretary overrides a state’s objection, the federal agency may authorize the activity.

State CZMA federal consistency reviews for oil and gas activities occur at three times: (1) when BOEMRE issues a lease sale for offshore oil and gas (A brief history of offshore oil drilling); (2) when an applicant submits an exploration plan to BOEMRE after obtaining a lease; and (3) when the applicant submits a development and production plan to BOEMRE after the exploration phase. State coastal management programs have concurred with over 10,000 exploration plans and over 6,000 development and production plans. Based on NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) data, states have reviewed tens of thousands of federal agency activities, federal license or permit activities, [Continental Shelf] oil and gas activities, and federal financial assistance activities since approval of the first coastal management plan in 1978. States have concurred with approximately 95% of these actions.69 There have been 141 appeals to the Secretary of Commerce, and 44 resulting appeals decisions.70 Of the 44 Secretarial decisions, 14 were related to [Continental Shelf] oil and gas activities, and those 14 decisions were evenly split (7 overrode state objection, 7 sustained state objection). Four of the oil and gas appeal decisions pertained to activities in the Gulf of Mexico – all in response to CZMA consistency objections that were filed by the State of Florida (three cases decided in 1993 and one case decided in 1995 – 2 overrode state objection, 2 sustained state objection).

Coastal Zone Management Act Issues for Commission Consideration

The BP oil spill demonstrated the potential for a spill to cover a massive geographic area, as well as the threat of oil from a spill in the Gulf of Mexico being carried to distant locations and coastlines via the Gulf of Mexico loop current and other ocean circulations. These lessons raise questions for consideration by the Commissioners related to the future interpretation of “reasonably foreseeable effects” under the CZMA federal consistency provision, and NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States)’s CZMA federal consistency regulations.71 NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States)’s current test for “reasonably foreseeable effects” is whether it is reasonably foreseeable that impacts that occur inside or outside of the state’s coastal zone will affect uses or resources of the state’s coastal zone (the activity or the coastal effects could occur inside or outside a state’s coastal zone).72

One question raised for Commissioners is whether the calculation of risk for an event like the BP oil spill should be increased by BOEMRE when determining reasonably foreseeable coastal effects under the CZMA.73 A second and related question is whether states with coastlines that are located at a “far” distance from [Continental Shelf] activities should have the right to review offshore oil and gas lease sales, exploration plans, and development and production plans under the CZMA due to the potential threat a catastrophic event may cause to the state’s coastal uses or resources. This question could be important as states like Florida, which has traditionally opposed [[offshore oil and gas (A brief history of offshore oil drilling)] activities], look to protect their ocean and coastal tourism and fishing industries from the possibility of a future large oil spill. A third question is whether it is “reasonably foreseeable” that oil from a spill in the Gulf of Mexico could be carried by currents to impact coastal uses or resources of states along the east coast. A fourth question is how the Secretary of Commerce should assess the risk/effects analysis from catastrophic events such as the BP oil spill when evaluating an appeal to a state’s objection under the CZMA. NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) and BOEMRE will need to carefully consider whether or not these seemingly geographically distant impacts meet a threshold for “reasonably foreseeable” in light of the BP oil spill.

Clean Water Act

Right whale and calf. Credit: NOAA Right whale and calf. Credit: NOAA

|

The Clean Water Act, originally passed as a 1972 amendment to the Federal Water Pollution Control Act, has the objective of restoring and maintaining the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the nation’s waters.74 The Act establishes the basic structure for regulating discharges of pollutants into the waters of the U.S. and for regulating surface water quality standards. Under the Clean Water Act, it is unlawful for any person to discharge any pollutant from a point source into U.S. waters without a National Pollution Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).75

The EPA regulates all waste streams generated from [Continental Shelf] oil and gas activities, following guidelines that are intended to prevent the degradation of the marine environment and that require an assessment of the effects of the proposed discharges on sensitive biological communities and aesthetic, recreational, and economic values.76 [Continental Shelf] oil- and gas-related issues that fall under the purview of the Clean Water Act include discharges into the waters of the United States from exploratory wells and development and production facilities (sanitary wastes, toxic pollutants, chemical oxygen demand, total organic carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, etc); oil discharges; and discharges of cooling water. In the Gulf of Mexico, BOEMRE inspectors perform most of the NPDES offshore platform compliance inspections for EPA.77 Additional inspections are performed by the U.S. Coast Guard Marine Safety Office.

EPA Region 6 reissued a NPDES [Continental Shelf] General Permit for existing and new source discharges in the central and western Gulf of Mexico off the coasts of Louisiana and Texas in October 2007 (expires September 2012). The remainder of the Gulf of Mexico is covered by an NPDES permit issued by EPA Region 4 in March 2010 (expires March 2015), including the [Continental Shelf] off the coasts of Florida, Alabama, and Mississippi. The Region 6 permit is the one that applies to the Macondo well lease site. It established effluent limitations, prohibitions, reporting requirements, and other conditions and discharges from oil and gas facilities and supporting pipeline facilities that are engaged in production, field exploration, developmental drilling, facility installation, well completion, well treatment operations, well workover, and abandonment or decommissioning operations.78

Clean Water Act Issues for Commission Consideration

No significant concerns regarding the Clean Water Act permitting process for offshore oil and gas activities in the Gulf of Mexico were raised during staff research or Commission hearings. However, as the Commissioners consider different regimes for BOEMRE offshore inspection, they may want to consider how enforcement of NPDES permits is integrated into the process.

Additional Areas for Commission Consideration

Sperm whale dives near deep-water industry platforms in Gulf of Mexico. Credit: BOEMRE Sperm whale dives near deep-water industry platforms in Gulf of Mexico. Credit: BOEMRE

|

In addition to the specific issues raised throughout this paper’s review of environmental consultations, authorizations, and permits, a number of broader issues relevant to environmental reviews for [Continental Shelf] oil and gas activities should also considered by the Commissioners:

- What is the best approach for strengthening the science and analyses underlying federal environmental reviews, interagency consultations, and permitting requirements for [[offshore oil and gas (A brief history of offshore oil drilling)] activities]? How can the science be better connected to the needs of the environmental regulatory processes?

- As the Commissioners consider different options for the reorganization of BOEMRE, what is the best structure to ensure that BOEMRE environmental reviews, oil spill risk analyses, and oil spill response plans are conducted with a high level of integrity, oversight, and independence from political influence? What structure will best ensure that the science stays connected to the environmental regulatory review and decisionmaking process within BOEMRE?

- Should NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service increase their frequency of interaction with BOEMRE related to the species and habitats over which they have statutory responsibilities? Should the three agencies be consulting informally more frequently throughout the oil and gas planning, exploration, and development process? Should NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States), the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and EPA conduct more frequent or more geographically precise environmental reviews for oil and gas activities?

- What level of additional resources and staff are needed to implement changes that will strengthen or expand environmental review and oversight of oil and gas activities at all of the relevant federal environmental agencies? Should dedicated funding for these activities be provided through the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund? Will additional environmental oversight actually serve to better protect the environment from the possible negative impacts of oil and gas activities?

- How can the different steps in the [Continental Shelf] leasing, exploration, and development process be changed to allow for more meaningful involvement by other federal agencies, states, tribes, and the public at the appropriate levels and stages of oil and gas activities?

Appendix I: Oil Spill Response Plans and Oil Spill Risk Analyses

Through authorities vested by the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 and Executive Order 12777, BOEMRE is responsible for oil-spill planning, preparedness, and select response activities for fixed and floating facilities engaged in exploration, development, and production of liquid hydrocarbons, and certain oil pipelines.79 This appendix will describe environmental aspects of the Oil Spill Response Plans, as well as discuss MMS/BOEMRE Oil Spill Risk Analyses.

Oil Spill Response Plans

Rough-toothed dolphin in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Credit: MMS Rough-toothed dolphin in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Credit: MMS

|

Oil Spill Response Plans are required by BOEMRE for all owners or operators of an oil handling, storage, or transportation facility that is located seaward of the coast line.80 Once approved, they are updated and reviewed by the BOEMRE regional office every two years, more frequently if there are major changes to the facilities or response capabilities. BOEMRE regulations outline the requirements for these plans, including their contents and directions for calculating the volume of oil in a worse case discharge scenario. Each owner/operator may submit a single plan that covers all of their facilities located in a BOEMRE region. The facility may be operated while waiting for BOEMRE approval of the plan if the owner/operators certify that they can respond to the maximum extent practicable to a worse case discharge or substantial threat of discharge. Additionally, if an owner/operator already has a plan approved by BOEMRE, the owner/operator is not required to immediately rewrite the plan to include new facilities – they may wait to add such facilities when the two year review period for their plan occurs.

According to the BOEMRE regulations, the response plan must include: an emergency response action plan; oil-spill response equipment inventory; oil-spill response contractual agreements; a calculation of the worst case discharge scenario; plan for dispersant use; in-situ burning plan; and information regarding oil-spill response training and drills.81 The emergency response plan is supposed to be the core of the overall plan, and is required to include information regarding the spill response team; the types and characteristics of oil at the facilities; procedures for early detection of a spill; and procedures to be followed in the case of a spill.82 In addition to the estimation of the volume of oil, a worse case discharge scenario discussion is required that includes trajectory analyses.83 The worst case scenario discussion is also required to include a list of the resources of special economic or environmental importance that could be impacted in the areas identified by the trajectory analysis, and strategies that will be used for their protection.

These requirements were further detailed in 2006 guidance issued by the MMS Gulf of Mexico Regional Office via Notice to Lessees (NTL). In this guidance, MMS provided information regarding the format for the plans and the information they should include. Rather than requiring the companies to provide rigorous analyses and geographically specific or detailed information in the plans, the guidance allows the regulatory requirements for sections to be met through the most basic information in many cases. For example, under the category of “resource identification,” the guidance requests only a discussion of the process that the company will use to identify resources and areas of special economic or environmental importance that could be impacted by the spill, rather than an identification of the resources and analysis of their vulnerability to oil spills. Similarly, under “strategic response planning,” the guidance requests only a discussion of process that the company will use to determine its response priorities and strategies.84

In the Gulf of Mexico BOEMRE Regional Office, plans are reviewed and approved by BOEMRE Field Operations, which also serves as the main regional liaison between BOEMRE and the industry. A limited number of plans are provided by Field Operations to the Gulf of Mexico Office of Leasing and Environment for review. Based on discussions with BOEMRE staff, the Commission staff found that Field Operations is heavily focused on the efficiency of the process, working to ensure that plans are reviewed and approved within 30 days of submission by industry.

The BP Oil Spill Response Plan in place for the Gulf of Mexico was dated June 2009. The plan inventory of facilities and pipelines lists 24 production platforms and structures in [Continental Shelf]waters, as well as 55 segments of pipeline. Although the Mississippi Canyon 252 lease block (site of the Deepwater Horizon incident) was technically covered by this plan, the location was not included in BP’s inventory of facilities. According to the BP plan, three worst case scenarios were selected to be analyzed based on “projected discharge volume, proximity to shorelines, areas of environmental and/or economic sensitivity, and marine and shoreline resources.” The plan noted that “the lack of significant differences between operations, products, resources, and sensitivities helped to establish potential discharge volume and location as the primary decisive factors for Worst Cast Discharge selections.”85 However, the BP plan fails to provide any analysis that supports this conclusion.

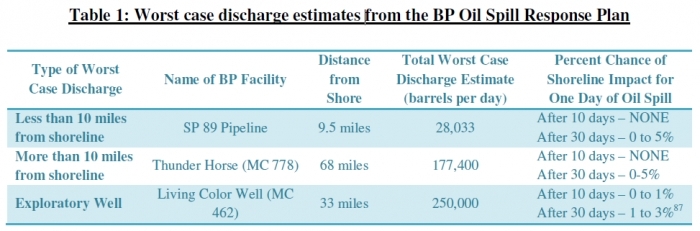

The three worst case discharge assessments included: a facility within ten miles of shore, a facility more than ten miles from shore, and an exploratory well. These categories of scenarios are outlined in the 2006 MMS guidance.86 The assessments assume maximum volumes from storage tanks and flowlines, pipelines, and daily production volume from an uncontrolled blowout. Estimates from the plan are summarized in Table 1 (below).

Despite the fact that these scenarios range from 28,033 barrels per day of discharge to 250,000 barrels per day of discharge, the BP Oil Spill Response Plan uses the exact same vague language to “analyze” shoreline impacts for each of the scenarios:

“If the spill went unabated, shoreline impact would depend on existing environmental conditions. Nearshore response may include the deployment of shoreline boom on beach areas, or protection and sorbent boom on vegetated areas. Strategies would be based upon surveillance and real time trajectories provided by The Response Group that depict areas of potential impact given the actual sea and weather conditions. Strategies from the Area Contingency Plan, The Response Group, and Unified Command would be consulted to ensure environmental and special economic resources would be correctly identified and prioritized to ensure optimal protection.”88

Sunrise over the Gulf of Mexico. Credit: NPS Sunrise over the Gulf of Mexico. Credit: NPS

|

The plan then directs the reader to other sections for more information on resource identification and resource protection methods. Both of these appendices are completely lacking in any form of analysis or specificity. Half of the “Resource Identification” appendix (5 pages) is copied from material on NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States)’s Environmental Sensitivity Index (ESI) websites. The information has not been edited for its applicability to the Gulf of Mexico. For example, the BP plan lists the full Environmental Sensitivity Index Shoreline Habitat Rankings without any discussion of which of those shoreline types are found in the Gulf of Mexico. Under the heading “Sensitive Biological and Human-Use Resources,” the plan includes the full list of resources that are included in NOAA’s nationwide description of ESI resources. As a result, the BP Oil Spill Response Plan for the Gulf of Mexico includes sea lions, sea otters, walruses and other resources that are not found in the Gulf of Mexico. The “Resource Protection Methods” appendix is equally as vague and lacking in applied analyses.

The BP Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill Response Plans for BP was prepared by a contractor that also prepared the Gulf of Mexico plans for Chevron, ConocoPhillips, ExxonMobil, Shell (along with other companies in the Gulf of Mexico). The result is five plans that are fairly close to identical. Although each has its own worst case scenario analysis calculations and trajectories, as well as other information filled into a basic template specific to the company and its assets, the broader analysis (or lack thereof) is almost exactly the same for each plan. This was a topic for a hearing by the House Subcommittee on Energy and Environment on June 15, 2010 that included as witnesses the CEOs or Presidents of BP, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, ExxonMobil, and Shell.

“Each of the five oil spill response plans also includes a section on responding to worst-case scenario involving an offshore exploratory well. On paper these plans look reassuring. BP's plan says it can handle a spill of 250,000 barrels per day. Both Chevron and Shell state they can handle over 200,000 barrels per day, and Exxon says it can handle over 150,000 barrels per day. That is far more oil than is currently leaking into the gulf of BP's well. But when you look at the details, it becomes evident these plans are just paper exercisers. BP failed miserably when confronted with a real leak, and one can only wonder whether ExxonMobil and the other companies would do any better. BP's plan says it contracted with the Marine Spill Response Corporation to provide equipment for a spill response. All the other companies rely on the same contractor.

BP's plan says another contractor will organize its oil spill removal. Chevron, Shell, and ExxonMobil use the same contractor. BP's plan relies on 22,000 gallons of dispersant stored in Kiln, Mississippi. Well, so do ExxonMobil and the other companies. I could go on, but I think you get my point. These are cookie-cutter plans. ExxonMobil, Chevron, ConocoPhillips and Shell are as unprepared as BP was and that is a serious problem. In their testimony and responses to questions the companies say they are different than BP, but when you examine their actual oil spill response plans and compare them to BP, it is hard to share their confidence.” ~Congressman Henry Waxman, Chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committee89

Despite the lack of analysis or geographic specificity, these Oil Spill Response Plans were approved by the Gulf of Mexico MMS Regional Office. ExxonMobil pointed this fact out in response to complaints about the content of their Oil Spill Response Plan, noting that they followed the 2006 MMS guidance for preparing the plan, and the plan was subsequently reviewed and approved by MMS.90 Although the regulations appeared to give MMS leverage to require more detailed and thorough analyses in the plans before they provide their approval, MMS did not require the companies to do so. The similar/identical content among the different oil company plans, as well as the overall failure of MMS to require meaningful analyses of Gulf of Mexico resources and clear strategies for their protection in case of an oil spill, raises a number of questions for the Commissioners regarding ways to improve the rigorousness of the MMS requirements and related review process. The Commissioners may also want to consider whether the worst case scenario spill calculations from these plans should be integrated into NEPA and other environmental reviews for oil and gas activities.91

Finally, Commission staff research has found a complete lack of transparency related to the Oil Spill Response Plans that likely exacerbated problems with insufficient content and analysis. First, the plans were not regularly provided to the environmental branch of the MMS Gulf of Mexico office for review. Second, the plans were not distributed to any other federal agencies for review and comment – including the U.S. Coast Guard or EPA. Third, the plans were not subject to any form of public review or comment before MMS approval, and were not available to the public after approval. All of these issues should be taken into consideration as the process for approving these plans is reviewed. In particular, Commissioners should consider whether additional BOEMRE staff and other federal agencies (U.S. Coast Guard, EPA, and NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States)) with expertise regarding different components of the Oil Spill Response Plans should review or provide clearance for the plans, whether a public comment period should be added before approval by BOEMRE, and whether finalized plans should be made public.

Oil Spill Risk Analysis

Kemp's Ridley sea turtles, Gulf of Mexico. Credit: NPS Kemp's Ridley sea turtles, Gulf of Mexico. Credit: NPS

|

The BOEMRE Oil Spill Modeling Program has the task of assessing oil-spill risks associated with offshore energy activities. This is done through the BOEMRE Oil Spill Risk Analysis model, which combines the probability of spill occurrence with a statistical description of hypothetical oil-spill movement on the ocean surface. The Oil Spill Risk Analysis is used to support BOEMRE Environmental Impact Statements for lease sales. The most recent Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill Risk Analysis was completed in June 2007, in preparation for the Central and Western Gulf of Mexico Planning Areas lease sales under the 2007-2012 [Continental Shelf] Program. The analysis covers all future operations that will occur during a 40-year time frame (2007-2046) under the Gulf of Mexico [Continental Shelf] Program.

The Oil Spill Risk Analysis is conducted in three parts: (1) calculation of the probability of oil spill occurrence based on spill rates derived from historical data and on estimated volumes of oil produced and transported; (2) calculation of trajectories of oil spills from hypothetical spill locations to locations of various environmental resources, which are simulated using the Oil Spill Risk Analysis Model; (3) the combination of results of the first two parts to estimate the overall oil-spill risk if there is oil development.92

1) Calculation of Oil Spill Occurrence Probability: In order to determine oil spill occurrence, the model relies upon spill rates from a 15-year period (1985-1999). The Oil Spill Risk Analysis report states that this data is the best representation of current technology.93

2) Calculation of Oil Spill Trajectories and Oil Interactions with Environmental Resources: The Oil Spill Risk Analysis Model simulates oil-spill transport using wind and ocean current data in the Gulf of Mexico. The result is a proxy for oil-spill trajectories. The model generates time sequences of hypothetical oil spill locations, which can be compared at each successive time step to the geographic boundaries of chosen environmental resources.94 Note that the model is calculating the trajectory for a 1-day spill event, and not a multi-day spill.

In order to choose the environmental resources to be included in the analysis, the Oil Spill Risk Analysis report notes that MMS staff consulted with staff from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.95 Environmental resources selected for analysis were: bird habitats (11 types of birds); Gulf sturgeon coastal habitat; beach mouse habitat (4 species); major recreational coastal areas (11 areas); coastal marine mammal habitats (9 areas); manatee habitats (9 areas); sea turtle nesting, mating, and general coastal habitat (30 types of habitats); coastal counties and parishes (48); offshore state waters (12 areas); and offshore state resources (5 areas). The analysis does not consider marine fishery resources and habitats; offshore marine mammal habitats and resources; offshore sea turtle resources and habitats – overall, it fails to consider most of the offshore environmental resources that are located outside of the coastal zone and are managed by NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States).96

3) Calculating Overall Oil Spill Risk: Results from the analysis are presented as the combined probability of spills both occurring and contacting modeled offshore and coastal environmental resource locations.97 The analysis estimates spill contacts with environmental resources, not impacts. The results of the analysis are presented in a series of tables that list the probability for each of the chosen environmental resources to be contacted by oil within 10 days of the 1-day spill event for both low and high oil resource production estimates.

Conclusion – Oil Spill Response Plans and Oil Spill Risk Analyses

Oil Spill Response Plans and Oil Spill Risk Analyses are both extremely important to the environmental review of [Continental Shelf] oil and gas activities. The Oil Spill Response Plans contain calculations of representative worst case oil spill scenarios for companies operating in [Continental Shelf] that should be factored into environmental reviews. Unfortunately, they did not appear to be connected to the MMS NEPA analyses, and were not made available to other federal agencies that were conducting environmental reviews of Gulf of Mexico oil and gas activities. In contrast, calculations from the MMS Oil Spill Risk Analysis were factored into MMS NEPA analyses, but resulted in significant underestimations of oil-spill impacts compared to the actual BP oil spill. Although one can argue that such a catastrophic event was not foreseeable, the BP Regional Oil Spill Response Plan for the Gulf of Mexico actually calculated a larger worst case discharge from an exploratory well than what occurred during the BP oil spill. Overall, staff research indicates that the Commissioners should consider how the content and review process for Oil Spill Response Plans can be improved to create a more meaningful program and plan focused on prevention, containment, and response. Additionally, Commissioners may want to consider ways that the environmental review process can better reflect the threat of oil spills to ecological resources in post-BP oil spill world.

End Notes

1 This staff working paper focuses on major ocean and coastal environmental laws that are applicable to oil and gas activities in the Gulf of Mexico. The Clean Air Act is not covered by this paper and the Clean Water Act is discussed only minimally. Broader NEPA issues are covered separately in Staff Working Paper No. 12.

2 16 U.S.C. §§ 1801 et seq.

3 Sustainable Fisheries Act, Pub. L. 104-297 (1996).

4 16 U.S.C. § 1802(10).

5 “What is Essential Fish Habitat?,” National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Marine Fisheries Service, Office of Habitat Conservation.

6 50 C.F.R. § 600.815(a)(8).

7 “What is Essential Fish Habitat?,” National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Marine Fisheries Service, Office of Habitat Conservation.

8 50 C.F.R. § 600.810(a) and § 600.910(a).

9 50 C.F.R. § 600.920(e).

10 On June 18, 2010, Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar signed Secretarial Order No. 3302, to reorganize the Minerals Management Service (MMS) into to the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation, and Enforcement. This staff working paper refers to MMS when discussing events that occurred or documents that were created before MMS was reorganized and renamed (to BOEMRE) in 2010.

11 50 C.F.R. § 600.925.

12 50 C.F.R. § 600.920(k) (1).

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Examples might include: anchoring and construction of structures and pipelines on the ocean floor; discharge of operational wastes (drilling fluids and cuttings, waste chemicals, fracturing and acidifying fluids, produced sand, well fluids, etc.); discharge of ballast or storage displacement water; and platform/structure removal.

16 A programmatic assessment is a broader analysis that covers multiple actions or areas. In this case, use of a programmatic assessment allows NOAA to evaluate the cumulative impacts of oil and gas operations across the Gulf of Mexico planning areas. According to NOAA guidelines, evaluation at a programmatic level may be appropriate when sufficient information is available to develop essential fish habitat conversation recommendations and address all reasonably foreseeable adverse impacts under a particular program area. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Marine Fisheries Service, Southeast Regional Office, Essential Fish Habitat: A Marine Fish Habitat Conservation Mandate for Federal Agencies – Gulf of Mexico Region (U.S. Department of Commerce, St. Petersburg, FL: September 2010).

17 Minerals Management Service, Essential Fish Habitat (EFH) Assessment for the Minerals Management Service Programmatic Consultation for Gulf of Mexico [Continental Shelf] (OCS) Oil and Gas Activities (New Orleans, LA: June 4, 1999).

18 Ibid, 4-5.

19 Ibid, 5.

20 Ibid, 5.

21 Ibid, 16.

22 Ibid, 16.

23 See Appendix I for a description of Oil Spill Response Plans.

24 Additional mitigation measures included: establishing no-activity and modified activity zones around topographic features through the MMS “topographic features stipulation”; deleting Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary from area-wide lease sales; requiring industry surveys to detect and avoid biologically sensitive areas; and using the MMS inspection program to ensure compliance with lease terms.

25 National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Marine Fisheries Service, Southeast Regional Office, Letter to the Minerals Management Service (U.S. Department of Commerce, St. Petersburg, FL: July 1, 1999).

26 Additional EFH Conservation Recommendations included: buffer zones to protect pinnacle trend features from bottom disturbing activities; additional protective requirements for the MMS “Topographic Features Stipulation” related to buffer zones, multiple well exploratory drilling, enforcement of sanctuary requirements, and documented damages to EFH; and a requirement for annual summaries to be provided to NOAA related to the number and type of permits that MMS issued in the Central and Western planning areas, areas with live bottom, and areas with topographic features.