Coastal and marine environments in Africa

Contents

Introduction

As coastal populations in Africa continue to grow, and pressures on the environment from land-based and marine human activities increase, coastal and marine living resources and their habitats are being lost or damaged in ways that are diminishing biodiversity (Coastal and marine environments in Africa) and thus decreasing livelihood opportunities and aggravating poverty. Degradation has become increasingly acute within the last 50 years. Arresting further losses of coastal and marine resources, and building on opportunities to manage the resources that remain in a sustainable way, are urgent objectives.

The main causes of this degradation, apart from natural disasters, are poverty and the pressures of economic development at local to global scales. Economic gains, many bringing only short-term benefits, are being made at the expense of the integrity of ecosystems and the vulnerable communities that they support. The over-exploitation of offshore fisheries impacts on the food security of coastal populations.

Another key concern is the modification of river flows to the coast by damming and irrigation, and pollution from land, marine and atmospheric sources.

Africa’s coastal and marine areas also have important non-living resources. There are offshore commercial oil and natural gas reserves in some 20 countries and many of these are being developed to supply the global energy market as well as domestic needs. Many countries in Western Africa, for example, are oil producers, with Cameroon, Gabon and Nigeria being net exporters. Alluvial diamond- and heavy mineral-bearing sands have long been worked from the coastal sediments of Southern Africa.

Exploitation of these non-living resources has damaged the coastal environment and, in the case of oil production in the Niger delta, caused civil conflict. Africa’s coastal environment is becoming an increasingly attractive destination for global tourism. In some countries, especially the small island developing states (SIDS), tourism, and its related services, is a main contributor to national economies.

Most countries recognize the value of their coastal and marine biodiversity and have gazetted marine and wetland protected areas to ensure their sustainability. The protection and restoration of Africa’s coastal and marine ecosystems and their services are long-term objectives for local to global communities. These objectives must be achieved in the face of the pressures from land-use change, including urbanization, and climate change, including the rising sea level, coastal erosion and lowland flooding. This demands policy approaches that are multisectoral and occur at multiple levels.

Resources

Africa’s mainland and island states have rich and varied coastal and marine resources, both living and nonliving. The coasts range from deserts to fertile plains to rain forest, from coral reefs to lagoons, and from high-relief, rocky shores to deeply indented estuaries and deltas. Their marine environments include the open Atlantic and Indian oceans and the almost landlocked Mediterranean and Red seas. Continental shelves, where waters are less than 200 m deep, in some places extend more than 200 km offshore, while elsewhere they are almost absent.

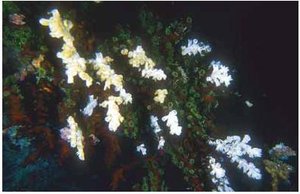

The biodiversity of the coastal zone is an important resource and there are many designated protected areas, both wetland and marine. The coral reefs, sea-grass beds, sand dunes, estuaries, mangrove forests and other wetlands that occur around many shores provide valuable services for humanity, as well as crucial nursery habitats for marine animals and sanctuaries for endangered species. The coral reefs, sea-grass beds, sand dunes, estuaries, mangrove forests and other wetlands that occur around many shores provide valuable services for humanity, as well as crucial nursery habitats for marine animals and sanctuaries for endangered species (Figure 1). Large Marine Ecosystems(LMEs) are relatively large regions, in the order of 200,000 km2 or greater, characterized by distinct bathymetry, hydrography, productivity, and trophically dependent populations. Many of these LMEs are characterized by seasonal or permanent coastal upwelling of cold, nutrient-rich oceanic water (where water is forced upwards from the ocean depths to the surface) supporting important fisheries.

During the last decade or so, substantial oil and natural gas resources have been discovered offshore, some of them in deep or ultra-deep water on the continental slope, as in Western Africa (Figure 2). Many offshore areas remain unexplored. The largest of the new oil reserves are those off the Niger delta, itself a globally important, established production area. Other major oil reserves have been discovered and are being developed within the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) of Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea and Angola. Many oil reserves are associated with natural gas. Large reserves of non-associated gas have been discovered offshore around the Gulf of Guinea – notably in Nigeria – and off Namibia and South Africa; also in the Mediterranean in the Gulf of Gabès and off the Nile delta. Natural gas is in production off the Tanzanian mainland.

Many of the coastal sediments of Southern and Eastern Africa yield mineral resources. The coastal sand dunes and seabed sediments along the Atlantic shores of South Africa and Namibia contain commercially valuable alluvial diamonds, while coastal sediments on South Africa’s Indian Ocean shores and in Mozambique contain commercial titanium and zirconium minerals. Coastal sands in Kenya are also a source of titanium.

Endowments and opportunities from resources

Africa’s marine and coastal resources have traditionally supported livelihoods through subsistence fisheries, agriculture and trading. Nowadays, the coastal areas are the locus of rapid urban and industrial growth, oil and gas development, industrial-scale fisheries and tourism (Figure 2). While there is a general trend of population increase in the coastal areas, the coastal cities are the principal growth nodes. It has been estimated that by 2025 the coastal zone from Accra to the Niger delta could be an unbroken chain of cities, with a total population of 50 million along 500 km of coastline (Figure 2). Much of the region’s heavy industry, including most refineries and gas liquefaction plants, is sited at coastal locations, along with terminal facilities for tankers and undersea pipelines, and bases for offshore engineering services.

(Source: WTO 2005)

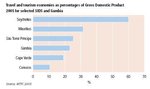

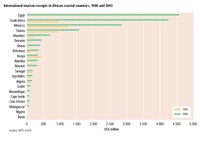

The natural coastal assets have supported a growth in tourism, with substantial economic benefits including the creation of many jobs for men and women. Tourism has become a big employer and source of income, notably in Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, Mauritius and South Africa (Figure 3). Many countries are set to further develop their coastal tourism, with an increasing market for eco- and cultural tourism. Tourism revenues were expected to grow by 5 to 10 percent in 2005, and annually, in real terms, by about 5 percent between 2006 and 2015. Much of this growth is likely to be coastal. Coral reefs are a major ecotourism attraction. There are opportunities for involving indigenous coastal communities in ecotourism, improving their well-being as well as contributing to national economies. In some countries – particularly some Small Island Developing States (SIDS) – tourism with its related services is already the largest employer and the tourism economy makes the largest contribution to Gross National Product (GNP) (Figure 4).

Artisanal fisheries are the mainstay of coastal communities’ livelihoods around much of Africa’s coastline, employing mostly men operating in small, undecked boats. Some countries, such as Morocco, Egypt, South Africa, Ghana and Senegal, have offshore industrial fishing fleets which employ mostly men, while men and women are engaged in the preparation of fish products onshore, as in the tuna canneries of Ghana, Seychelles and Mauritius. Intertidal harvesting for shellfish or maricultured seaweed, as in Tanzania, is carried out by women.

The extent to which coastal communities, and their countries, benefit from fisheries resources varies greatly, as shown in Figure 5. The resources are exploited by industrial as well as artisanal fleets, the former comprising local and foreign-flag vessels. Where the artisanal sector is strong, as on the Atlantic coast, all vessels operate in about the same areas, targeting similar species, and this often leads to conflict between artisanal and industrial fleets. Cases of poaching and illegal, unregulated and unreported (IUU) fishing by vessels from outside the region are common, the latter jeopardizing the catches of local, small-scale fishers with serious consequences for food security and income. Increases in industrial-scale fishing over the last decade or so have impacted adversely on artisanal fisheries, already stressed through population pressure by over-harvesting and the use of unsustainable fishing methods. Generally, artisanal fisheries are showing decreasing returns per fishing effort and reductions in the sizes of fish caught.

(Source: FAO fisheries Department)

Countries whose EEZs extend into the areas of oceanic upwelling in the Atlantic LMEs tend to be major, industrial producers of marine fish, much of it taken by foreign fleets under access agreements. In Eastern Africa, Somalia could benefit from the rich fisheries of the Somali Current upwelling, but much of its production is captured illegally. In the Western Indian Ocean, fisheries contribute significantly to all national economies, with stocks including tuna exploited under licence by foreign fleets. Fish processing and transhipment provides additional employment and revenue. In Mozambique and Tanzania, estuarine prawn fisheries make an important economic contribution. In the Mediterranean, where foreign industrial fleets are becoming prevalent, there may still be some scope for increased production, but at the expense of the size of fish caught. Total reported marine fish capture continues to increase, with nearly 5 million t recorded in 2003 (Figure 5). In the last three decades, imports of fish and fishery products by African countries exceeded the exports of the same in quantity, although the gap is gradually decreasing. Conversely, export values were far in excess of import values. This is because many African countries import large quantities of low-grade species, like mackerel and sardinellas, and export highgrade species like shrimps and snappers, and other demersal species.

Aquaculture makes important contributions to the livelihoods of coastal dwellers in Egypt, particularly fish from the brackish water lagoons of the Nile delta. In Zanzibar, Tanzania, seaweed farming has become important, improving livelihoods particularly of women. Few countries have seized the opportunities of aquaculture, although considerable potential exists across the region. For sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), it is estimated that less than 5 percent of the potential has been utilized, contributing less than 0.2 percent to world aquaculture production.

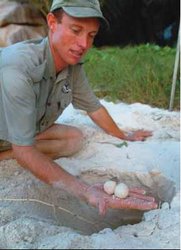

In addition to fishery resources, coastal and marine ecosystems provide important services. Coral reefs and their associated sea-grass meadows and mangrove forests, and other coastal wetlands, provide nursery areas and shelter for a host of animals, both marine and terrestrial, as well as protection against inundation and erosion by marine storm surges and extreme waves (Figure 1). Mangrove forests act as chemical cleansing buffers, absorbing landsourced pollutants, and they also have cultural and medicinal values. Beaches and dune systems provide coast protection as well as sites for nesting and breeding. Offshore oil and gas development is making substantial contributions to national economies, providing jobs for men, though many of these are short term. With the engagement of industry and effective national governance, the benefits to coastal communities and the protection of coastal and marine ecosystems could be substantially improved. In many countries, hydrocarbon development is supplying growing domestic and transnational energy markets. The value of the resources to national economies is difficult to estimate because of the volatile nature of the global energy market and the nature of specific licensing arrangements. The sums involved are potentially huge. But these resources are finite and the income generated from their production cannot be sustainable over the long term. The alluvial mineral resources of Southern Africa are similarly finite, and these too make substantial economic contributions.

Development challenges

The capacity of most coastal nations to utilize their coastal and marine assets, while simultaneously protecting them from degradation, is lacking. Although the success of coastal tourism is subject to local security issues as well as global economic pressures, its sustainability depends, above all, on the protection and beneficial management of those assets. The region’s fisheries have scope for restoration and continuing to be major contributors to coastal livelihoods, and the national economy, but only if the pressures leading to overexploitation and pollution can be controlled. Oil and natural gas development and mineral extraction have a potential for increasing the general levels of economic security and human well-being in the short to medium term, but these resources are finite and there is a need to diversify into sustainable ventures.

The overexploitation of fisheries at artisanal and industrial scales using unsustainable fishing methods, and the introduction to coastal ecosystems of invasive alien species from marine sources, are further concerns. Coastal ecosystems, especially estuaries and lagoonal wetlands, are becoming increasingly impacted by activities within river catchment, with deforestation, intensive agriculture, damming and irrigation all changing the nature of material fluxes (water, sediment, nutrients and pesticides). At the global scale, human-induced atmospheric warming has been contributing to a slow but persistent eustatic sealevel rise and significant climatic changes in the region. In the last decade, episodes of unusually high sea temperatures have caused widespread mortality of reef coral.

A summary of the principal issues faced in realizing development opportunities is given in Table 1.

Empowerment and capacity

The will and capacity of countries to manage their coastal and marine resources in ways that promote human wellbeing, for present populations and for future generations, are important issues. Effective governance at community to global levels is a prerequisite for environmental stewardship, while the development and maintenance of that stewardship depends on a sustained commitment to human and technical capacity-building. Such capacitybuilding encompasses scientific data collection and monitoring, the construction of appropriate legal frameworks, and improving capabilities in surveillance and the enforcement of legislation. Capacity-building in monitoring and enforcement at community level offers important opportunities. Community-based or participatory monitoring has been very effective in increasing the manpower available for monitoring (thus cost-effective) and at the same time enhancing environmental awareness and ownership among community members. This has been effective in mangrove and coral reef monitoring in Tanzania.

In order to develop and maintain environmental stewardship, there must be sustained commitment to finance, human and operational capacity-building, as well as to the promotion of public awareness. Capacity-building should include the development of appropriate institutions and legal frameworks, scientific data collection and monitoring, and capabilities in surveillance, as well as the monitoring and enforcement of legislation. There is a clear need for the development of professional, technical and managerial staff in each of the priority areas and activities identified in Table 2.

Collaboration and cooperation

Most coastal countries are signatories to one or more multilateral environmental agreement (MEA) that deals with marine and coastal management issues. These MEAs include the Barcelona Convention, the Jeddah Convention, the Nairobi Convention and the Abidjan Convention, as well as the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) relating to the control of pollution from ships, and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). These conventions lay the foundations for coastal states to develop legislation and management plans relating to their coastal and marine environments, integrating the various sectoral policies and, increasingly, taking account of river catchment that discharge to those environments. Under Article 76 of UNCLOS, a state may submit proposals to extend its defined continental shelf beyond the 200-nautical mile limit of its EEZ for the purposes of mineral extraction and harvesting benthic organisms. Some countries have introduced legislation for coastal management.

Recognizing the transnational issues involved in an ecosystem-wide approach to catchment, coastal and marine resource management, national legislation and management plans should place a priority on the coordination of sector interests, with the involvement of all resource users. Policies should reflect the marked increase in environmental degradation over the last 50 years or so, as well as acknowledge the priorities for taking action.

Partnerships with global actors are increasingly important in addressing coastal and marine management issues. Initiatives for improving resource management and related capacity-building are in place through organizations such as the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO (IOC), the World Bank, The Regional Organization for the Conservation of the Environment of the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden (PERSGA), LOICZ (Land-Ocean Interactions in the Coastal Zone), WWF – the World Wide Fund For Nature (WWF), IUCN- the World Conservation Union (IUCN) and UNEP. These initiatives, along with many bilateral agreements, commonly have overlapping objectives and there would be merit in improved coordination and cooperation amongst the various organizations and donors.

Destruction and pollution

Key issues in the management of the coastal zone and offshore waters include the loss of biodiversity and habitats through human-related pressures, the impacts of which have become increasingly acute within the last 50 years or so. Physical destruction and pollution of habitats from land-based and marine sources as a consequence of economic development is rife. For example, the clearance of mangroves for local consumption and export, as well as land clearance for agriculture and fuelwood leading to siltation, threaten marine life.

Competition for space is intense around developing cities, where urban sprawl is making inroads into coastal wetlands and disturbing them through land-filling, pollution and eutrophication. Elsewhere, agriculture is impinging on wetlands, with drainage schemes and pollution from fertilizers and pesticides. Mangrove forests, which provide an invaluable range of ecological services and products, including pollution filtering and coastal defence, are especially vulnerable to development pressure from overharvesting (eg for construction poles) and clearance for agriculture, prawn ponds and salt pans. They are also being stressed by reduced freshwater supply due to damming. Protected area status provides little assurance from the impacts of these competing economic activities. One challenge is how to deal with oil and gas exploration in or adjacent to marine protected areas (MPAs).

Unsustainable fisheries

Overexploitation of fisheries has two main drivers – at the artisanal scale, poverty and population growth (including the inward migration of fishers) amongst coastal communities (an added difficulty is that many fishers will not easily accept alternative means of livelihood) and, at the industrial scale, commercial incentives and subsidies available to foreign fleets operating under licence, or in some cases illegally, in Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs).

Economic and social benefits accruing to western coastal countries, in particular those arising from access agreements with distant water fleets, have generally not been realized (though the case of Namibia is an exception) and few coastal people benefit directly from access fees in terms of direct or indirect employment or in improved standards of living. There will be serious consequences for rural coastal populations if the degradation of fisheries, through overharvesting (inshore and offshore) and the use of damaging methods, continues unchecked. Fishing access agreements in the coastal states are signed by various ministries, each with their own development agenda and no common goal. Although the extent of stocks may be poorly known, countries continue to sign agreements with foreign fleets who may take advantage of the lack of surveillance and fish beyond their agreed quotas.

The fish stocks in most of the LMEs around Africa, as in the rest of the world’s oceans, are overexploited, and where catch tonnages are increasing, as in the Mediterranean, there are reductions in the sizes of fish caught. The resulting by-catch (non-target species) also poses a threat to biodiversity. Effective enforcement of regulations concerning fishing methods, such as the minimum allowable net mesh sizes, is needed if stocks are to attain maturity. Without the recognition by the international community of the precarious state of most of the offshore fisheries, there is a real danger that stocks will collapse. There is an urgent need for international agreement on fisheries regulation, as well as for financial support for monitoring, control and surveillance, and for enforcement of regulation. Most countries do not yet have the management and operational capacity to fully develop their EEZs to their own long-term economic advantage, although those of the Western Indian Ocean have recently come together (with the help of WWF) to set up minimum terms and conditions for fishing access. With this capacity in place, there should be opportunities to restore the fisheries resources to a sustainable level. There is also a great need for capacity-building in the area of negotiations. Data collection and the development of inventories remain a challenge. In the region as a whole, the quality of reported statistics for fisheries, especially for fish catches, numbers of fishers and fishing boats, is varied and in some cases unreliable.

Tourism

Coastal tourism development has the potential for longterm benefits to coastal communities and national economies, but it also raises important issues of sustainability. For sites of mass tourism, the construction of hotels and transport infrastructure involves habitat loss, while the pressures of tourist numbers – through physical disturbance, high demand for freshwater, pollution and eutrophication – impact adversely on the living resources, especially those of coral reef ecosystems. The short-term aspirations of developers must be appraised in the longer-term contexts of the sustainability of the amenity that has attracted those developers in the first place and of the implications of climate change. In particular, tourism development should aim to avoid the sidelining and alienation of indigenous communities by involving them in ecotourism.

Coastal accretion and erosion

Much of Africa’s coastal zone is vulnerable to physical shoreline change, in some places from accretion, but mostly from erosion. Most of the change is due to, or exacerbated by, human activities. Locally, it is caused by coastal engineering, such as port development interrupting the longshore transport of protective beach sediment. More widely, it is due to the retention (by damming) of river-borne sediments formerly discharged at the coast, as in the case of the Nile delta. Short of dismantling existing dams, there is little that can be done in mitigation other than installing expensive coastal defences. Coastal erosion and the progressive flooding of coastal lowlands are likely to increase, largely as a consequence of the rise in sea level produced by global warming. Apart from catastrophic temporary inundations caused by tsunamis or climate-driven marine surges, physical shoreline change is usually a slow process, and the most cost-effective solutions for threatened communities will be those involving adaptation by planned relocation. The long-term impact of sea-temperature rise (resulting from climate change) on the integrity of the region’s coral reefs is likely to be profound.

Incentives and empowerment for coastal communities to sustainably manage and develop the resources upon which they depend should be considered at the national level. Payments for the use of ecosystem services by developers and harvesters of all sorts may provide a pathway for this. The valuation of ecological services is not simple, but global knowledge in this field is fast developing. “Cap and trade” schemes, similar to those being applied to the production of gases such as carbon dioxide, can be applied to fisheries, for example, with quotas being tradable between countries or smaller stakeholders. With or without such incentives, the promotion of public awareness is important if Africa and its coastal communities are going to benefit from their coastal and marine resources over the long term.

Conclusion

(Source: J. Tack/Still Pictures)

The continuing capacity of the region’s coastal and marine ecosystems to provide the goods-and-services that are essential to human well-being will depend on the effectiveness of ecosystem management in response to the pressures of global change. Such management requires reliable monitoring information gathered from community to global levels and needs to be supported by nationally and internationally relevant legislation. Robust governance and institutional capacity, and the cooperative integration of sectoral interests at all scales, are essential. Response and compliance mechanisms should involve education as well as local and cultural knowledge. The enforcement of international agreements need to be strengthened, along with the promotion of public awareness and the enhancement of capacity for implementation, surveillance and enforcement, using remote sensing techniques as appropriate. Key research aims are to improve understanding of the causal linkages within, and affecting, the coastal and marine ecosystems, and of the value of the ecosystem’s services to humanity in order to appropriately inform policymakers and to provide the information that resource managers need to act effectively within policy frameworks.

The development and application of integrated coastal management (ICZM or ICAM) plans should be promoted, with strong inter-sectoral and international linkages, including those with catchment management authorities with responsibilities for Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM). The impacts of reduced freshwater and sediment discharge from rivers on coastal ecosystems and stability are a particular concern.

Action in terms of consultation, cooordination and the implementation of relevant legislation, at various levels, is urgently needed to halt the degradation of coastal and marine fisheries (industrial, subsistence and artisanal) and to restore their sustainability for the benefit of coastal communities and national economies. Effective monitoring and surveillance capacity will be needed to achieve this goal. Remedial measures need to be agreed at the international and ecosystem levels, with a clear understanding of the long-term negative consequences for human wellbeing of non-compliance. Regional cooperation, such as the BCLME programme, in the management of widespread or shared migratory stocks should be seen as essential rather than only an opportunity. Protection of artisanal fisheries in the face of population pressure and industrial-scale fishing is an urgent issue and directly impacts on well-being and the ability of countries to meet the income and nutritional targets of the MDGs. Recognizing the potential for aquaculture development, appropriate regulations are needed to protect coastal ecosystems, and to promote sustainable production practices.

Management of existing protected areas requires increased public awareness, financial support and political will, with stronger enforcement of national and international laws. Coral reefs and coastal wetlands must be rigorously protected within an integrated management framework, involving local fishermen in monitoring where feasible.

Water- and airborne pollution control measures, including coastal and catchment point and diffuse sources, as well as offshore oil and gas fields, should be obligatory, with financial incentives for compliance and penalties for non-compliance. The issues of solid waste management and of marine-transported litter impacting shores need urgent attention, particularly as they affect SIDS. The latter requires international cooperation, with a strengthening of adherence to MARPOL – the Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships.

The management of coastal erosion and marine inundation in the context of global climate change is a particularly difficult challenge, involving cooperation at local to global levels, as well as the adoption of interlinkages approaches as discussed in Interlinkages: the environment and policy web in Africa. Longterm planning for adaptation to sea-level rise and increased storminess should be instituted by all coastal managers, especially urban authorities. Coastal development, including tourism infrastructure, should reflect a shoreline’s susceptibility to change, with appropriate setback regimes and the relocation of vulnerable communities.

Much of the region’s coastline is exposed to extreme tsunami waves and to storm-driven marine surges that generate unusually high sea levels. Learning from the lessons of the Indian Ocean tsunami of December 2004, the development of an early warning system for these extreme marine hazards should be a priority, as well as the promotion of public awareness and emergency procedures.

Further reading

- Alder, J. and Sumaila, U.R., 2004. Western Africa: A fish basket of Europe past and present. Journal of Environment and Development. 13(2), 156-78.

- Alm, A., 2002. Pdf Integrated Coastal Zone Management in the Mediterranean: From Concept to Implementation – Towards a Strategy for Capacity Building in METAP Countries. Mediterranean Environmental Technical Assistance Program.

- Coffen-Smout, S., 1998. Pirates, Warlords and Rogue Fishing Vessels in Somalia’s Unruly Seas.

- Crossland, C.J., Kremer, H.H., Lindeboom, H.J., Marshall Crossland, J.I. and Le Tissier,M.D.A., eds. 2005. Coastal Fluxes in the Anthropocene –The Land-Ocean Interactions in the Coastal Zone Project of the International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme. Global Change – the International Geosphere-Biosphere Program Series. Springer, Berlin.

- EIA, 2005. Country Analysis Briefs. Energy Information Administration.

- FAO, 2005. FAOSTAT Database. Fisheries Data. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Francis, J. and Torell, E., 2004. Human dimensions of coastal management in the Western Indian Ocean region. Ocean and Coastal Management. 47 (7-8), 299-307.

- Groombridge, B. and Jenkins, M., 2002. World Atlas of Biodiversity: Earth’s Living Resources in the 21st Century. University of California Press, Berkeley.

- Hatziolos, M., Lunden, C.G. and Alm, A., 1996. Africa: A Framework for Integrated Coastal Zone Management. Second edition. The World Bank, Washington, D.C.

- IPCC, 2001. Climate Change 2001: Synthesis Report. A Contribution of Working Groups I, II, and III to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds.Watson, R.T. and the Core Writing Team). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Lindeboom, H., 2002. The Coastal Zone:An Ecosystem Under Pressure. In Oceans 2020: Science,Trends and the Challenge of Sustainability (eds. Field, J,G., Hempel, G., and Summerhayes, C.P.), pp. 49-84. Island Press, Washington.

- MA, 2005. Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Biodiversity Synthesis. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Island Press,Washington, D.C.

- Pauly, D., Christensen,V., Guénette, S., Pitcher,T.J., Rashid Sumaila, U., Walters, C.J.,Watson, R. and Zeller,D., 2002. Towards sustainability in world fisheries. Nature. 418, 689-95.

- Sherman, K. and Alexander, L.M. (eds. 1986). Variability and Management of Large Marine Ecosystems.American Association for the Advancement of Science Selected Symposia Series, No.99. Westview Press, Boulder.

- UNEP, 2001. Eastern Africa Atlas of Coastal resources, Tanzania. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi.

- UNEP, 2004. Ocean Islands. Global International Waters Assessment, Regional Assessment 45b. University of Kalmar, Kalmar, Sweden.

- UNEP, 2006. Africa Environment Outlook 2

- UNEP/GRID-Arendal, 2004. UNEP Shelf Programme. United Nation Environment Programme / Global Resource Information Database –Arendal.

- UNEP/MAP/PAP, 1999. Conceptual Framework and Planning Guidelines for Integrated Coastal Area and River Basins Management. United Nations Environment Programme /Mediterranean Action Plan /Priority Actions Programme.

- UNEP-WCMC, 2000. Marine Information. United Nations Environment Programme’s World Conservation Monitoring Centre.

- WCD, 2000. Dams and Development:A New Framework for Decisionmaking, The Report of the World Commission on Dams. Earthscan Publications, London.

- WTTC, 2005. Country League Tables – Travel and Tourism: Sowing the Seeds of Growth – The 2005 Travel & Tourism Economic Research. World Travel and Tourism Council, London.

|

|

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |