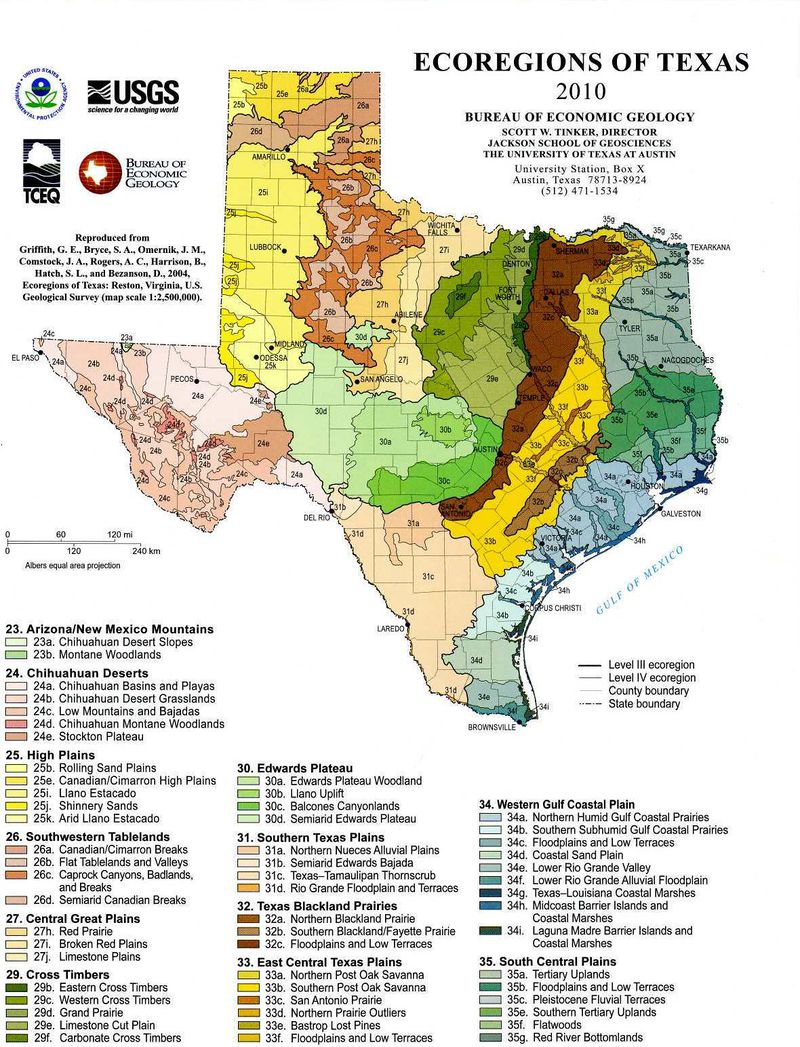

Ecoregions of Texas (EPA)

http://www.lib.utexas.edu/geo/pics/ecoregionsoftexas.jpg http://www.lib.utexas.edu/geo/pics/ecoregionsoftexas.jpg

|

| http://www.lib.utexas.edu/geo/pics/ecoregionsoftexas.jpg |

Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, and quantity of environmental resources. They are designed to serve as a spatial framework for the research, assessment, management, and monitoring of ecosystems and ecosystem components. By recognizing the spatial differences in the capacities and potentials of ecosystems, ecoregions stratify the environment by its probable response to disturbance (Bryce and others, 1999). These general purpose regions are critical for structuring and implementing ecosystem management strategies across federal agencies, state agencies, and nongovernment organizations that are responsible for different types of resources within the same geographical areas (Omernik and others, 2000).

The approach used to compile this map is based on the premise that ecological regions are hierarchical and can be identified through the analysis of the spatial patterns and the composition of biotic and abiotic phenomena that affect or reflect differences in ecosystem quality and integrity (Wiken 1986; Omernik 1987, 1995). These phenomena include geology, physiography, vegetation, climate, soils, land use, wildlife, and hydrology. The relative importance of each characteristic varies from one ecological region to another regardless of the hierarchical level. A Roman numeral hierarchical scheme has been adopted for different levels of ecological regions. Level I is the coarsest level, dividing North America into 15 ecological regions. Level II divides the continent into 52 regions (Commission for Environmental Cooperation Working Group 1997). At level III, the continental United States contains 104 ecoregions and the conterminous United States has 84 ecoregions (United States Environmental Protection Agency [USEPA] 2003). Level IV, depicted here for the State of Texas, is a further refinement of level III ecoregions. Explanations of the methods used to define the USEPA’s ecoregions are given in Omernik (1995), Omernik and others (2000), and Gallant and others (1989).

Ecological and biological diversity of Texas is enormous. The state contains barrier islands and coastal lowlands, large river floodplain forests, rolling plains and plateaus, forested hills, deserts, and a variety of aquatic habitats. There are 12 level III ecoregions and 56 level IV ecoregions in Texas and most continue into ecologically similar parts of adjacent states in the U.S. or Mexico.

The level III and IV ecoregions on this poster were compiled at a scale of 1:250,000 and depict revisions and subdivisions of earlier level III ecoregions that were originally compiled at a smaller scale (USEPA 2003; Omernik 1987). This poster is part of a collaborative project primarily between USEPA Region VI, USEPA National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory (Corvallis, Oregon), Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ), and the United States Department of Agriculture-Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). Collaboration and consultation also occurred with the United States Department of the Interior-Geological Survey (USGS)-Earth Resources Observation Systems Data Center, and with other State of Texas agencies and universities.

The project is associated with an interagency effort to develop a common framework of ecological regions (McMahon and others, 2001). Reaching that objective requires recognition of the differences in the conceptual approaches and mapping methodologies applied to develop the most common ecoregion-type frameworks, including those developed by the United States Forest Service (Bailey and others, 1994), the USEPA (Omernik 1987, 1995), and the NRCS (U.S. Department of Agriculture-Soil Conservation Service, 1981). As each of these frameworks is further refined, their differences are becoming less discernible. Regional collaborative projects such as this one in Texas, where some agreement has been reached among multiple resource management agencies, are a step toward attaining consensus and consistency in ecoregion frameworks for the entire nation.

| 23. Arizona/New Mexico Mountains The Arizona/New Mexico Mountains are distinguished from neighboring mountainous ecoregions by their lower elevations and an associated vegetation indicative of drier, warmer environments, due in part to the region’s more southerly location. Forests of spruce, fir, and Douglas-fir, common in the Southern Rockies (21) and the Wasatch and Uinta Mountains (19), are only found in limited areas at the highest elevations in this region in Arizona and New Mexico. Chaparral is common at lower elevations; pinyon-juniper and oak woodlands are found at lower and middle elevations; and the higher elevations, outside of Texas, have mostly open to dense ponderosa pine forests. | |

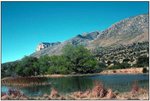

| 23a. The Chihuahuan Desert Slopes of the Guadalupe Mountains in Texas form the leading edge of a giant uplifted Permian reef created from the accumulated remains of algae, sponges, and marine bivalves. The 2000 foot high, white cliff face of the southern Guadalupe Mountains dominates the landscape of the northern Trans-Pecos of Texas. The lower slopes of the mountains, composed of eroded limestone, shale, and sandstone, represent a continuation of the Chihuahuan Desert ecosystem; soils and vegetation in much of Ecoregion 23a are similar to those in the Low Mountains and Bajadas (24c) of the Chihuahuan Deserts ecoregion (24). There is some evidence that the lower Guadalupe Mountains were once grasslands overgrazed in the late 19th century and subsequently invaded by desert shrubs. Yucca, sotol, lechuguilla, ocotillo, and cacti now dominate the rocky slopes below 5500 feet. These shrub species are sometimes called succulent desert shrubs to distinguish them from shrubs such as creosotebush typically found in the drier Chihuahuan Basins and Playas (24a). Grasslands persist near alluvial fans and on gentle slopes with deeper, sandstone-derived soils. Water is scarce; the few streams that originate from springs at higher elevations do not persist beyond the mouths of major canyons. Several lizard species that are adapted to the exposed, sun-baked landscape of West Texas are indicative of the succulent desert shrubland: the round-tailed horned lizard, the checkered whiptail, and the greater earless lizard. |

|

| 23b. The Montane Woodlands ecoregion covers the higher slopes of the Guadalupe Mountains above 5500 feet with densities of juniper, pinyon pine, and oak varying according to aspect. At middle elevations, a chaparral community occurs beneath the trees, composed of shrubs such as desert ceanothus, alderleaf mountain mahogany, and catclaw mimosa. The top of the plateau is grassy and park-like with scattered trees. A limited area of Douglas-fir, southwestern white pine, and ponderosa pine appears at the highest elevations, forming an outlier of the type of forests that prevail at similar elevations elsewhere in the Arizona/New Mexico Mountains (23) where more moisture is available. However, these patches of high elevation conifers are too small to map at this scale. The east and west faces of the Guadalupe Mountains are cut by a series of canyons. Surface water is scarce. Infiltrating rainfall percolates through the limestone, creating caverns throughout the range and a few springs that emerge from sandstone layers at 6000 feet or below. The canyons support a high number of endemic plant species due in part to their isolation as relics of a wetter climate. McKittrick Creek is considered a perennial stream, although it often runs underground and ends at the mouth of its canyon. The riparian areas surrounding the springs are oases of velvet ash, chinkapin oak, Texas madrone, bigtooth maple, maidenhair fern, and sawgrass. Mule deer, reintroduced elk, black bear, mountain lion, and the only chipmunk in Texas, the gray-footed chipmunk, are protected within Guadalupe Mountains National Park. | |

|

24. Chihuahuan Deserts | |

|

24a. The Chihuahuan Basins and Playas ecoregion includes alluvial fans, internally drained basins, and river valleys below 3500 feet. The major Chihuahuan basins in Ecoregion 24a, such as the Hueco, Salt, and Presidio basins, formed during the Basin and Range tectonism when the Earth’s crust stretched and fault collapse resulted in sediment-filled basins. These low elevation areas represent the hottest and most arid habitats in Texas, with less than 12 inches of precipitation per year. Precipitation amounts are highest in July, August, and September, and winter precipitation is relatively sparse. The playas and basin floors have saline or alkaline soils and areas of salt flats, dunes, and windblown sand. The typical desert shrubs and grasses growing in these environments, such as creosotebush, tarbush, fourwing saltbush, blackbrush, gyp grama, and alkali sacaton, must withstand large diurnal ranges in temperature, low available moisture, and an extremely high evapotranspiration rate. The alien saltcedar and common reed have invaded riparian areas. Land use, particularly grazing, is limited in desert areas due to sparse vegetation and lack of water. However, limited areas of agriculture exist near El Paso and Dell City, where irrigation water is available to produce cotton, pecans, alfalfa, tomatoes, onions, and chile peppers. |

|

| 24b. The Chihuahuan Desert Grasslands occur in areas of fine-textured soils, such as silts and clays, that have a higher water retention capacity than coarse-textured, rocky soil. The grasslands occur in areas of somewhat higher annual precipitation (10 to 18 inches) than the Chihuahuan Basins and Playas (24a), such as elevated basins between mountain ranges, low mountain benches and plateau tops, and north-facing high mountain slopes. Grasslands in West Texas were once more widespread, but grazing pressure in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was unsustainable, and desert shrubs invaded where the grass cover became fragmented. In grassland areas with lower rainfall, areal coverage of grasses may be sparse, 10% or less. Typical grasses are black, blue, and sideoats grama, bush muhly, tobosa, beargrass, and galleta, with scattered creosotebush and cholla cactus. Effective management strategies for grasslands take into account their fragile and erosive nature. | |

| 24c. The Low Mountains and Bajadas ecoregion includes disjunct areas scattered across West Texas that have a mixed geology: Permian-age sandstone, limestone, and shale in the Apache and Delaware Mountains; Cretaceous-age limestone on the Stockton Plateau and southward along the Rio Grande; and Tertiary-age volcanic rocks in the Chisos and Davis Mountains. The mountainous terrain has shallow soil, exposed bedrock, and coarse rocky substrates. Alluvial fans of rubble, sand, and gravel build at the base of the mountains and often coalesce to form bajadas. Vegetation includes mostly desert shrubs, such as sotol, lechuguilla, yucca, ocotillo, lotebush, tarbush, and pricklypear, with a sparse intervening cover of black grama and other grasses. At higher elevations, there may be scattered one-seeded juniper and pinyon pine. Strips of gray oak, velvet ash, and little walnut etch the patterns of intermittent and ephemeral drainages, and oaks may spread up north-facing slopes from the riparian zones. The varied habitats provide cover for mule deer, bobcat, collared peccary, and Montezuma quail. | |

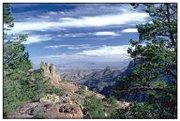

| 24d. The Chihuahuan Montane Woodlands ecoregion comprises the higher elevation mountainous areas above 5000 feet, mainly in the Chisos, Davis, Glass, and Apache Mountains. Increased precipitation in the mountains supports woodland areas except on sunny, exposed slopes that may have grass and chaparral only. Springs are few even at high elevations and mid-elevation streams may flow only during heavy rains. Oaks, junipers, and pinyon pines predominate on all these mountain ranges. Ponderosa pine and some relict Douglas-fir grow at the highest elevations in the Chisos Mountains. Higher elevation sites in the Davis Mountains also support ponderosa pine, southwestern white pine, and whiteleaf oak forests. In these ranges, trees sometimes grow with a grassy understory, or with a brush cover of bigtooth maple, madrone, little walnut, oak chaparral, and grapevines. The higher mountainous areas are a major refuge for larger ungulates, such as mule deer, desert bighorn sheep, and reintroduced elk. | |

| 24e. The Stockton Plateau ecoregion is similar geologically to the Edwards Plateau (30), but it differs ecologically. Geologically, it is a continuation of the Cretaceous-age limestone that forms the Edwards Plateau, but it is located west of the Pecos River in the dry climatic conditions of West Texas. The character of Ecoregion 24e is transitional to the arid grassland and desert shrub habitats of the Chihuahuan Desert to the west. Its mesa topography is more sharply defined than the rounded profiles of hills in the Edwards Plateau due to a lack of precipitation and associated chemical weathering. The mesa tops are sparsely covered by honey mesquite brush and either redberry or Ashe juniper. Mohr oak and Vasey oak, both shrubby in growth form, replace the plateau live oak that is common on the Edwards Plateau. The lower elevations on the Stockton Plateau are covered with Chihuahuan Desert shrubs and grama grasses. | |

| 25. High Plains Higher and drier than the Central Great Plains (27) to the east, and in contrast to the irregular, mostly grassland or grazing land of the Northwestern Great Plains (43) to the north, much of the High Plains is characterized by smooth to slightly irregular plains with a high percentage of cropland. Grama-buffalograss is the potential natural vegetation in this region compared to mostly wheatgrass-needlegrass to the north, Trans-Pecos shrub savanna to the south, and taller grasses to the east. The northern boundary of this ecological region is also the approximate northern limit of winter wheat and sorghum and the southern limit of spring wheat. Oil and gas production occurs in many parts of the region. | |

| 25b. The Rolling Sand Plains expand northward from the lip of the Canadian River trough, and they are topographically expressed as flat sandy plains or rolling dunes. In northern Texas, the vegetative cover of the Rolling Sand Plains is transitional between the Shinnery Sands (25j) to the south and the sandsage prairies of Oklahoma and Kansas. Havard shin oak, the characteristic shrub cover of the Shinnery Sands, still grows in the Texas portion of Ecoregion 25b, but it is at the northern limit of its distribution. However, both Havard shin oak and sand sagebrush perform the same important function of stabilizing sandy areas subject to wind erosion. The goal of both agricultural and grazing management is to keep enough vegetative cover on the land surface to minimize wind erosion. The sandsage association includes grasses such as big sandreed, little bluestem, sand dropseed, and sand bluestem. Lesser prairie-chickens use both shin oak and sandsage prairie habitats, but are presently imperiled due to agricultural conversion to modern farming practices as well as intensive grazing. |

|

| 25e. The Canadian/Cimarron High Plains ecoregion includes that portion of the Llano Estacado that lies north of the Canadian River in the Texas Panhandle. Winters are more severe than on the Llano Estacado (25i); the increased snow accumulation delays summer drought conditions because the snowmelt saturates the ground in the spring season. Although the topography of 25e is just as flat as the rest of the Llano Estacado, the northern portion has fewer layas, and it is more deeply dissected by stream channels. There is also more grazing land in Ecoregion 25e; the rougher terrain near the stream incisions tends to be grazed rather than tilled. In cultivated areas, corn, winter wheat, and grain sorghum are the principal crops. | |

| 25i. The Llano Estacado ecoregion, translated as the “Staked Plain”, is an elevated plain surrounded by escarpments on three sides. Geologically, the Llano Estacado began as an apron of Miocene-Pliocene sediments (Ogallala Formation) eroded from the eastern Rocky Mountains that was eventually covered by Pleistocene wind-borne sand and silt. Several caliche horizons developed in the Ogallala sediments, including a hardened caprock caliche in the uppermost layer. The Pecos River captured the headwater streams of rivers that once ran across the plain from the Rockies, isolating the Llano Estacado and truncating the drainage areas of the Red, Brazos, and Colorado rivers of Texas. As a result, the dry plain, cut off from a mountain surface water source and with little slope to induce runoff, has a very low drainage density. Instead, the smooth surface of the plain holds seasonal rainfall in myriads of small intermittent ponds or playas. The Llano Estacado was once covered with shortgrass prairie, composed of buffalograss, blue and sideoats grama, and little bluestem. An estimated 7 million bison once populated the southern High Plains. They were the most prominent elements of a prairie ecosystem that no longer functions as an interdependent web of bison, black-tailed prairie dog, black-footed ferret, snake, ferruginous hawk, coyote, swift fox, deer, pronghorn, mountain lion, and gray wolf. The Llano Estacado is presently 97% tilled for agriculture. Farmers produce cotton, corn, and wheat under dryland agriculture or irrigated with water pumped from the Ogallala Aquifer. In the era before irrigation, agriculture was not sustainable during drought cycles; the Llano Estacado formed the core of the Dust Bowl during the drought years of the 1930’s. The capacity of the Ogallala Aquifer is limited, particularly under drought conditions, emphasizing the need for enhancement and expansion of ongoing water conservation practices for agricultural and urban users. | |

| 25j. The Shinnery Sands ecoregion is named for the Havard oak brush that stablizes sandy areas subject to wind erosion. The disjunct areas include sand hills and dunes as well as flat sandy recharge areas. The largest area, at the southwestern edge of the Llano Estacado, is composed of sands most likely blown out of the Pecos River Basin against the western escarpment of the Llano Estacado. While sand sagebrush and prairie grasses such as sand dropseed, sand bluestem, and big sandreed may create a continuous plant cover in portions of Ecoregion 25j, the shrub and forb cover may be sparse in dune areas. The shinnery sands are habitat for the lesser prairie-chicken, a species that is in serious decline. The shrubs offer cover and shade for nesting, and shin oak acorns are a staple food source. The decline of the prairiechicken is linked to the conversion of shinnery to other uses. | |

| 25k. The Arid Llano Estacado ecoregion is drier than the main portion of the Llano Estacado (25i) to the north. Its climate is transitional to the arid Trans-Pecos region to the southwest (Ecoregion 24). It has somewhat more broken topography and fewer playas than the plain (25i) to the north. There is also less winter precipitation and snow cover to provide lasting moisture over the summer months. The arid conditions are reflected in the land use, which is dominated by livestock grazing and more recently irrigated peanut production. Oil and gas production activities are widespread. | |

| 26. Southwestern Tablelands The Southwestern Tablelands flank the High Plains (25) with red hued canyons, mesas, badlands, and dissected river breaks. Unlike most adjacent Great Plains ecological regions, little cropland occurs in the Southwestern Tablelands. Much of this region is in sub-humid grassland and semiarid rangeland. The potential natural vegetation in this region is grama-buffalograss with some mesquite-buffalograss in the southeast, juniper-scrub oakmidgrass savanna on escarpment bluffs, and shinnery (midgrass prairie with low oak brush) along parts of the Canadian River. Soils in this region include Alfisols, Inceptisols, Entisols, and Mollisols. | |

| 26a. The Canadian/Cimmaron Breaks ecoregion is a broad erosional incision between the High Plains (25) and the Central Great Plains (27). During the Pleistocene, the Canadian River carried much more water than it does today, in draining the meltwater from glaciers in the Rocky Mountains to the west. The river’s erosional force was great enough to cause the headward erosion of the edge of the High Plains. The dissolution of underlying salt beds and subsequent collapse of overlying rocks helped to create the deep trench of the Canadian River. Erosion has not penetrated deeply enough in the Texas portion of this region, however, to expose the Permian red beds that are prominent in the Cimarron Breaks to the north and east. The primary surficial deposit is the Ogallala Formation. |

|

|

26b. The Flat Tablelands and Valleys ecoregion includes islands of level land between the prominent buttes, badlands, and escarpments of the tablelands. Geologically, the surficial composition of these flat areas may be undissected Triassic or Permian red beds, or (in western portions) the Ogallala caprock that is found on the Llano Estacado (25i) to the west. The soils are predominately fine sandy loams or silt loams; as a result, most of Ecoregion 26b has been tilled to produce cotton, sorghum, and wheat. There is a trend toward desertification in Ecoregion 26 which is more subtle than that in the Chihuahuan Desert country of West Texas (24). Fragments of remaining native prairie are composed of mid-height grasses, such as sideoats grama and blue grama, typical of a wetter climate. Where the land has been intensively grazed, short grasses such as buffalograss predominate, and invading cacti and honey mesquite are common. Saltcedars are replacing native vegetation in riparian areas. | |

| 26c. The Caprock Canyons, Badlands, and Breaks ecoregion covers the broken country extending eastward from the eroded edge of the High Plains (25). The escarpment at the eastern edge of the Llano Estacado (25i) exposes Ogallala Formation sediments, underlying multicolored Triassic shales, mudstones, and sandstones, and Permian red beds with white gypsum deposits that form the plains to the east. The maximum relief along the escarpment is 1100 feet; the combination of topography and climate in Ecoregion 26c creates thunderstorms and tornadoes in the spring and early summer. Along the escarpments, redberry junipers grow on the rimrock and cliff faces, along with skunkbush sumac, ephedra, mountain mahogany, plum, grape, and clematis. Mohr shin oak and Havard oak are found on the benches and slopes, and honey mesquite on the flat valley floors. Riparian vegetation includes cottonwood, willow, hackberry, and big bluestem grasses with alien elms and saltcedars. Steep slopes, runoff, and salinity in badland areas limit vegetation to a sparse growth of yucca, cacti, ephedra, or sandsage. | |

| 26d. The Semiarid Canadian Breaks ecoregion is similar to Ecoregion 26a to the east with its broad valleys and moderate-relief tablelands, although this region is drier. Some flora found in Ecoregion 26a tend to drop out towards the west in 26d. The shrub and midgrass prairie vegetation includes juniper, sand sagebrush, skunkbush sumac, and yucca, along with sideoats grama and little bluestem. Fringes of cottonwood, willow, and hackberry occur along some streams. Invasive saltcedars have become established along many bottomlands, and honey mesquite has also increased in the region. Human population is sparse, with large ranches and land use devoted primarily to livestock grazing and hunting leases. The exotic aoudad, or Barbary sheep, released in the mid-20th century as a trophy game animal, has increased in the breaks and competes with the native mule deer for browse. | |

| 27. Central Great Plains The Central Great Plains are slightly lower, receive more precipitation, and are more irregular than the High Plains (25) to the west. The ecological region was once grassland, a mixed or transitional prairie from the tallgrass in the east to shortgrass farther west. Scattered low trees and shrubs occur in the south. Most of the ecoregion is now cropland. The eastern boundary of the region marks the eastern limits of the major winter wheat growing area of the United States. Soils in this region are generally deep with shallow soils on ridges and breaks. | |

| 27h. The broken tablelands of Ecoregion 26c flatten out to form the gently rolling Red Prairie ecoregion. Erosion by the Brazos and Colorado rivers has removed the overlying Cretaceous limestones to expose the Permian sedimentary rocks. The Central Great Plains ecoregions form a shallow trough between the High Plains (25) to the west and the more rugged topography of the Cross Timbers (29) to the east and Edwards Plateau (30) to the south. Precipitation amounts are considerably greater than on the High Plains, although they are not high enough to support forest vegetation. Prairie type may be midgrass or shortgrass dependent upon soil type, moisture availability and grazing pressure. Typical grasses include little bluestem, Texas wintergrass, white tridens, Texas cupgrass, sideoats grama, and curlymesquite. Much of the Red Prairie is under cultivation. |

Some areas in the Texas portion of the Central Great Plains contained grasslands, which were transitional from tallgrass to shortgrass prairie. Bluestems, gramas, Texas wintergrass, and buffalograss were typical. Many areas of Ecoregion 27 in Texas are now dominated by more brushy species, such as mesquite and lotebush. These invasive species tend to increase with overgrazing, soil erosion, lowering of ground water tables, and the decline of native grasslands. Some areas in the Texas portion of the Central Great Plains contained grasslands, which were transitional from tallgrass to shortgrass prairie. Bluestems, gramas, Texas wintergrass, and buffalograss were typical. Many areas of Ecoregion 27 in Texas are now dominated by more brushy species, such as mesquite and lotebush. These invasive species tend to increase with overgrazing, soil erosion, lowering of ground water tables, and the decline of native grasslands. |

| 27i. The soils of the Broken Red Plains ecoregion are red clay and sand, similar to that on the Red Prairie (27h). However, the topography of Ecoregion 27i is more irregular and more shrub-covered, although the prevalence of honey mesquite may be the result of grazing pressure. The line of 30 inches annual precipitation (or about the 98th meridian) marks the eastern limit of the distribution of mesquite and the eastern boundary of Ecoregion 27i. As in Ecoregion 27h, the prairie type is transitional between tallgrass and shortgrass growth forms. Besides honey mesquite, wolfberry, sand sagebrush, yucca, and pricklypear cacti may be mixed with the grasses. Riparian vegetation includes cottonwood, hackberry, cedar elm, pecan, and little walnut. In contrast to land use practices in Ecoregion 27h, the Broken Red Plains are used mainly for grazing. | |

| 27j. The Limestone Plains ecoregion is composed of thin strata of Permian-age limestone, sandy limestones, and mudstone. The Limestone Plains are covered by mixed grass prairie of little bluestem, yellow Indiangrass, and buffalograss, with scattered honey mesquite. However, upland soils are often thin, rocky, and droughty in the vicinity of limestone outcrops. Drier (or eroded) areas support desert shrubs such as lotebush, agarita, tree cholla, and ephedra. The Central Great Plains (27) are typically treeless except in riparian areas, but at the southern end of Ecoregion 27j, scattered plateau live oak grow with the mesquite shrub, in transition to the live oak-mesquite-juniper woodland of the adjacent Edwards Plateau (30). As in some other limestone-based ecoregions in Texas (such as 29d, 29e, 30a), land use is dominated by grazing rather than cultivated agriculture. A minor amount of wheat or sorghum may be grown in deeper alluvial soils. | |

| 29. Cross Timbers | |

| The Cross Timbers ecoregion is a transitional area between the once prairie, now winter wheat growing regions to the west, and the forested low mountains or hills of eastern Oklahoma and Texas. The region stretches from southern Kansas into central Texas, and contains irregular plains with some low hills and tablelands. It is a mosaic of forest, woodland, savanna, and prairie. The Cross Timbers ecoregion is not as arable or as suitable for growing corn and soybeans as the Central Irregular Plains (40) to the northeast. The transitional natural vegetation of little bluestem grassland with scattered blackjack oak and post oak trees is used mostly for rangeland and pastureland, with some areas of woody plant invasion and closed forest. Oil production has been a major activity in this region for over eighty years. | |

| 29b. The Eastern Cross Timbers ecoregion covers a more confined area than the Western Cross Timbers (29c). The ecoregion occurs on sandy substrates (Woodbine Sand) lying between the Grand Prairie (29d) and Texas Blackland Prairies (32) in eastern Texas. The soils are mainly red and yellow sands that have been leached of nutrients. Post oaks and blackjack oaks have adapted to life in sandy soils and they dominate the overstory, with scattered honey mesquite and grasses, such as little bluestem and threeawn, growing beneath them. Although the rural land use is predominantly cattle grazing, there is some farming for peanuts, grain sorghum, pecans, peaches, and vegetables. Extensive urban development also occurs within this region. |

|

| 29c. The Western Cross Timbers ecoregion covers the wooded areas west of the Grand Prairie (29d) on sandstone and shale beds. The landscape has cuesta topography consisting of sandstone ridges with a gentle dip slope on one side and a steeper scarp on the other. The soils are mostly fine sandy loams with clay subsoils that retain water. As in the Eastern Cross Timbers (29b), the dominant trees are post oak and blackjack oak with an understory of greenbriar, little bluestem, and purpletop grasses. Some researchers contend that these woodland areas would be savanna-like if they experienced fire, although one early account described the Cross Timbers as “an immense natural hedge” or belt of thick impenetrable forest. It is likely that there were more prairie openings between the belts of forest. The area has a long history of coal, oil, and natural gas production from the Pennsylvanian sandstone/limestone/shale beds. Deeper soils in the eastern part of this ecoregion support a dairy industry, pastureland, and cultivation of forage sorghum, silage, corn, and peanuts. | |

| 29d. The Grand Prairie is an undulating plain underlain by Lower Cretaceous limestones with interbedded marl and clay. Although the vegetation of the Grand Prairie is similar to the Northern Blackland Prairie (32a), the limestone of the Grand Prairie is more resistant to weathering, which gives the topography a rougher appearance. Meandering streams deeply incise the limestone surface. The original vegetation was tallgrass prairie in the upland areas and elm, pecan, and hackberry in riparian areas where deeper soils have developed in floodplain deposits or where the underlying clays have been exposed by limestone erosion. The invasive species Ashe juniper and, to a lesser extent, honey mesquite have increased since settlement. Grand Prairie grasses include big bluestem, yellow Indiangrass, little bluestem, hairy grama, Texas wintergrass, sideoats grama, and Texas cupgrass. Some common Great Plains animals, such as black-tailed jackrabbit and the scissortail flycatcher, range farther east through the Grand Prairie, creating an overlap in Great Plains and eastern forest species. Present land uses include grazing on ridges with shallow soils and farming of corn, grain sorghum, and wheat on the deeper soils on the flats. | |

| 29e. Mesas alternate with broad intervening valleys in the stairstep topography of the Limestone Cut Plain. Ecoregion 29e is underlain by Lower Cretaceous limestones, including the Glen Rose Formation and Walnut Clay, that are older than the limestone of the Edwards Plateau (30). The Glen Rose Formation has alternating layers of limestone, chert, and marl that erode differentially and generally more easily than the Edwards Limestone. The effects of increased precipitation and runoff are also apparent in the increased erosion and dissolution of the limestone layer. The Limestone Cut Plain has flatter topography, lower drainage density, and a more open woodland character than the Balcones Canyonlands (30c). The vegetation of Ecoregion 29e is similar to that of the Balcones Canyonlands, but less diverse: post oak, white shin oak, cedar elm, Texas ash, plateau live oak, and bur oak are prevalent. Although the grasslands of the Limestone Cut Plain are a mix of tall, mid, and short grasses, some consider it a westernmost extension of the tallgrass prairie, which distinguishes this ecoregion from the Edwards Plateau Woodland (30a). Grasses include big bluestem, little bluestem, yellow Indiangrass, silver bluestem, Texas wintergrass, tall dropseed, sideoats grama, and common curlymesquite. | |

| 29f. The Carbonate Cross Timbers ecoregion is that portion of the Western Cross Timbers (29c) that has Pennsylvanian or Cretaceous limestone substrate. This area is not included on some maps of the Cross Timbers, because it does not support the typical oak woodland of the sandstone-based territory surrounding it. The topography of Ecoregion 29f is also somewhat different from that of the Western Cross Timbers (29c) as it contains low mountains rather than alternating ridges and shallow basins. The limestone substrate is apparent in the vegetation cover, which has more plateau live oak, honey mesquite, and pure Ashe juniper woodland than in other surrounding Cross Timbers areas. The juniper woodlands are particularly dense. It is presumed that before widespread fire suppression, the area was less wooded and more savannah-like. | |

| 30. Edwards Plateau | |

| This ecoregion is largely a dissected limestone plateau that is hillier to the south and east where it is easily distinguished from bordering ecological regions by a sharp fault line. The region contains a sparse network of perennial streams. Due to karst topography (related to dissolution of limestone substrate) and resulting underground drainage, streams are relatively clear and cool in temperature compared to those of surrounding areas. Soils in this region are mostly Mollisols with shallow and moderately deep soils on plateaus and hills, and deeper soils on plains and valley floors. Covered by juniper-oak savanna and mesquite-oak savanna, most of the region is used for grazing beef cattle, sheep, goats, exotic game mammals, and wildlife. Hunting leases are a major source of income. Combined with topographic gradients, fire was once an important factor controlling vegetation patterns on the Edwards Plateau. It is a region of many endemic vascular plants. With its rapid seed dispersal, low palatability to browsers, and in the absence of fire, Ashe juniper has increased in some areas, reducing the extent of grassy savannas. | |

| 30a. The Edwards Plateau Woodland ecoregion contains the central part of the Edwards Plateau north of the highly dissected Balcones Canyonlands (30c). It encompasses the portion of the Edwards Plateau that receives sufficient rainfall to support woodland in contrast to the drier portion of the plateau to the west (30d) that has open juniper woodland and brush. The profile of the hills is rounded due to increased precipitation and chemical weathering. The dissection is moderate compared to the higher dissection of the Balcones Canyonlands (30c) to the south. Historically, the Edwards Plateau was a savanna of grasslands with scattered plateau live oak, Texas oak, Ashe juniper, and honey mesquite. With fire suppression and grazing, Ashe juniper and mesquite have spread, reducing the savanna character of the plateau. The grasslands of Ecoregion 30a are considered a southern extension of the mixed grass prairie, expressed as tallgrass or shortgrass dependent upon soil type, moisture availability, and grazing pressure. Grasses include little bluestem, Texas wintergrass, yellow Indiangrass, white tridens, Texas cupgrass, sideoats grama, seep muhly, and common curlymesquite. |

The dissected southeast portion of the Edwards Plateau is an area of canyonlands with a diversity of flora and fauna. The Cretaceous-age Glen Rose Limestone provides abundant water through seeps, springs, and cool, clear streams that support the deciduous woodland and associated wildlife. (Carlo Abbruzzese) The dissected southeast portion of the Edwards Plateau is an area of canyonlands with a diversity of flora and fauna. The Cretaceous-age Glen Rose Limestone provides abundant water through seeps, springs, and cool, clear streams that support the deciduous woodland and associated wildlife. (Carlo Abbruzzese) |

| 30b. The Llano Uplift ecoregion is actually a basin; in some places, it is 1000 feet below the level of the surrounding limestone escarpment. It gets its name from the granitic mass (batholith) that is exposed in the basin, granite that has been dated at one billion years old. Upland soils are shallow, reddish brown, stony, sandy loams over granite, gneiss, and schist with deeper sandy loams in the valleys. Soils tend to be acidic in contrast to the alkaline soils of the Edwards Plateau Woodland (30a) surrounding Ecoregion 30b. The woody vegetation has elements of both 30a and the Cross Timbers (29b and 29c), with plateau live oak, honey mesquite, post oak, blackjack oak, cedar elm, and some black hickory present depending on aspect and habitat. Flora normally found in the deserts of West Texas, such as catclaw mimosa and soaptree yucca, also occur on dry sites. Ashe juniper and Texas oak are generally absent from the Llano Uplift; they are found mainly on the slopes of the limestone escarpment surrounding the basin or on limestone inclusions. Grasses include little bluestem, switchgrass, yellow Indiangrass, and silver bluestem. Dome-like granite hills and outcrops contain unusual plant communities. Although ranching is the major land use, level areas of sandy loam produce wheat, sorghum, and peaches. | |

| 30c. The Balcones Canyonlands ecoregion forms the southeastern boundary of the Edwards Plateau (30). The Edwards Plateau was uplifted during the Miocene epoch at the Balcones Fault Zone, separating central Texas from the coastal plain. The Balcones Canyonlands are highly dissected through the erosion and solution of springs, streams, and rivers working both above and below ground; percolation through the porous limestone contributes to the recharge of the Edwards Aquifer. High gradient streams originating from springs in steep-sided canyons supply water for development on the Texas Blackland Prairies (32) at the eastern base of the escarpment. Ecoregion 30c supports a number of endemic plants and has a higher representation of deciduous woodland than elsewhere on the Edwards Plateau (30), with escarpment black cherry, Texas mountain-laurel, madrone, Lacey oak, bigtooth maple, and Carolina basswood. Some relicts of eastern swamp communities, such as baldcypress, American sycamore, and black willow, occur along major streamcourses. It is likely that these trees have persisted as relics of moister, cooler climates following the Pleistocene glacial epoch. Toward the west, the vegetation changes gradually as the climate becomes more arid. Plateau live oak woodland is eventually restricted to north and east facing slopes and floodplains, and dry slopes are covered with open shrublands of juniper, sumac, sotol, acacia, honey mesquite, and ceniza. | |

| 30d. The Semiarid Edwards Plateau ecoregion lies west of the 100th meridian, where precipitation amounts are too low to support closed canopy forest. Although the geologic foundation of Ecoregion 30d, Cretaceous limestone, is the same as the rest of the Edwards Plateau, the shape of the landscape differs from that further east because of the relative lack of precipitation. The profiles of the hills are sharp, not rounded, because erosion occurs mainly through rockfall at the margins of mesas rather than through limestone dissolution. Canyons break the surface; most streams are intermittent, but perennial streams have the character of those in the wetter central Edwards Plateau to the east. Although honey mesquite, Ashe juniper, and plateau live oak are still present in Ecoregion 30d, live oak is restricted to floodplains. Other arid-land shrubs become more common: lotebush, lechuguilla, sotol, and redberry juniper. Short grasses, such as buffalograss, tobosa, and black grama become more common in the west and northwest portions of Ecoregion 30d as the climate becomes more arid. | |

| 31. Southern Texas Plains This rolling to moderately dissected plain was once covered in many areas with grassland and savanna vegetation that varied during wet and dry cycles. Following long continued grazing and fire suppression, thorny brush, such as mesquite, is now the predominant vegetation type. Ceniza and blackbrush occur on caliche soils. Also known as the Tamualipan Thornscrub, or the “brush country” as it is called locally, the region has its greatest extent in Mexico. The subhumid to dry region contains a diverse mosaic of soils, mostly clay, clay loam, and sandy clay loam surface textures, and ranging from alkaline to slightly acid. The ecoregion also contains a high and distinct diversity of plant and animal life. It is generally lower in elevation with warmer winters than the Chihuahuan Deserts (24) to the northwest. Oil and natural gas production activities are widespread. | |

| 31a. The Northern Nueces Alluvial Plains ecoregion differs from much of Ecoregion 31 due to greater precipitation (22-28 in.), numerous streams that flow from the Balcones Canyonlands (30c), transitional vegetation patterns, different mosaic of soils and surficial materials, and land cover that includes more cropland and pasture. Broad Holocene and Pleistocene-age alluvial fans and other alluvial plain deposits characterize the region. The region has a hyperthermic soil temperature regime with aridic ustic and typic ustic soil moisture regimes. Soils are mostly very deep, moderately fine-textured and medium-textured. Mollisols and Alfisols are typical, with some Inceptisols. General vegetation types include some mesquitelive oak-bluewood parks in the north, and mesquite-granjeno parks in the south. Some open grassland with scattered honey mesquite, plateau live oak, and other trees occur. Little bluestem, sideoats grama, lovegrass tridens, multiflowered false rhodesgrass, Arizona cottontop, plains bristlegrass, and other mid grasses are dominant on deeper soils. Open grassland with scattered low-growing brush, such as guajillo, blackbrush, elbowbush, and kidneywood, characterize shallower soils. Arizona cottontop, sideoats grama, green sprangletop, and false rhodesgrass are dominant mid grasses on these soils. Some floodplain forests may have hackberry, plateau live oak, pecan, and cedar elm, with black willow and eastern cottonwood along the banks. Cropland is common, but large areas are used as rangeland. The main crops are corn, cotton, small grains, and vegetables. Most cropland areas are irrigated. Hunting leases for white-tailed deer, northern bobwhite, and mourning dove are an important source of income. |

The composition of the thornscrub and shrub savannas is variable across Ecoregion 31, influenced by substrate and grazing practices. Typical brush on the caliche ridge shown here includes ceniza, blackbrush, guajillo, and mesquite. Common plants in other areas are huisache and other acacias, along with guayacan, amargosa, yuccas, and Texas prickly pear. Typical grasses are silver bluestem, multiflowered false rhodesgrass, plains bristlegrass, purple threeawn, and grama species. The composition of the thornscrub and shrub savannas is variable across Ecoregion 31, influenced by substrate and grazing practices. Typical brush on the caliche ridge shown here includes ceniza, blackbrush, guajillo, and mesquite. Common plants in other areas are huisache and other acacias, along with guayacan, amargosa, yuccas, and Texas prickly pear. Typical grasses are silver bluestem, multiflowered false rhodesgrass, plains bristlegrass, purple threeawn, and grama species. |

| 31b. The Semiarid Edwards Bajada ecoregion is composed primarily of alluvial fan and slope wash deposits below the escarpment of the Edwards Plateau (30). Although not omposed of karstic Edwards Limestone nor physiographically part of Ecoregion 30, Ecoregion 31b contains springs and streams that show some similarities to those of the Edwards Plateau (30) because they flow over a chalky substrate and likely originate from cool water aquifers beneath the Edwards Plateau. The very presence of perennial streams in such an arid region is distinctive. Elevations are lower and the climate is warmer than on the Edwards Plateau (30), and the vegetation, primarily blackbrush and honey mesquite, is more typical of the rest of the Southern Texas Plains (31). | |

| 31c. Covering a large portion of the Southern Texas Plains, the Texas-Tamaulipan Thornscrub ecoregion encompasses a mosaic of vegetation assemblages and a variety of soils. This South Texas region owes its diversity to the convergence of the Chihuahuan Desert to the west, the Tamaulipan thornscrub and subtropical woodlands along the Rio Grande to the south, and coastal grasslands to the east. Composed of mostly gently rolling or irregular plains, the region is cut by arroyos and streams, and covered with low-growing vegetation. The thorn woodland and thorn shrubland vegetation is distinctive, and these Rio Grande Plains are commonly called the “brush country”. Three centuries of grazing, suppression of fire, and droughts have contributed to the spread of brush and the decrease of grasses. Soils include hyperthermic Alfisols, Aridisols, Mollisols, and Vertisols. They are varied and complex, highly alkaline to slightly acidic, ranging from deep sands to clays and clay loams. Caliche outcroppings and gravel ridges are common. Precipitation is bimodal, with peak rainfall occurring in spring and fall. Spring rains are the result of frontal activity, while fall precipitation is usually tropical in origin. Typically, transpiration and evaporation far exceed input from precipitation. Precipitation is erratic, with extreme year-to-year moisture variation. Droughts are common and frequently severe. The vegetation is dominated by drought-tolerant, mostly smallleaved, and often thorn-laden small trees and shrubs, especially legumes. The most important woody species is honey mesquite. Where conditions are suitable, there is a dense understory of smaller trees and shrubs such as brasil, colima or lime pricklyash, Texas persimmon, lotebush, granjeno, kidneywood, coyotillo, Texas paloverde, anacahuita, and various species of cacti. Xerophytic brush species, such as blackbrush, guajillo, and ceniza, are typical on the rocky, gravelly ridges and uplands. The brush communities also tend to grade into desert scrub near the Rio Grande. Mid and short grasses are common, including cane bluestem, silver bluestem, multiflowered false rhodesgrass, sideoats grama, pink pappusgrass, bristlegrasses, lovegrasses, and tobosa. Most of the area is rangeland and large ranches raise beef cattle. Ranching income is supplemented with hunting leases. Northern bobwhite and white-tailed deer are important game species. Hunting also occurs for mourning doves, wild turkey, and collared peccary. Cultivated land is minimal, with mostly grain sorghum, small grains, cotton, and watermelons. | |

| 31d. The Rio Grande Floodplain and Terraces are relatively narrow in Texas, but this region is an important natural and cultural feature of the state. Draining more than 182,000 square miles in eight states of Mexico and the United States, the Rio Grande Basin is one of the largest in North America. The river is generally sluggish and its water flow in this section is controlled in part by two large dams, Amistad above Del Rio, and Falcon below Laredo. The region consists of mostly Holocene alluvium or Holocene and Pleistocene terrace deposits, with a mix of ustic to aridic, hyperthermic soils. Some floodplain forests occurred, especially in the lower portion of the region, with species such as sugar hackberry, cedar elm, and Mexican ash. These species are generally more typical downstream in 34f. Riparian forests have declined as natural floods have been restricted by flood-controlling dams and water diversions. Brushy species from adjacent dry uplands occur at the margins, such as honey mesquite, huisache, blackbrush, and lotebush, with some grasses such as multiflowered false rhodesgrass, sacaton, cottontop, and plains bristlegrass. Wetter areas near the river may have black willow, black mimosa, common and giant reed, and hydrophytes such as cattails, bulrushes, and sedges. Many of the wider alluvial areas of the floodplain and terraces are now in cropland, mostly with cotton, grain sorghum, and cool-season vegetables. The arid or semi-arid climate of the Rio Grande Basin, the over-allocation of actual water, and the difficulties of binational management contribute to serious water resource, environmental, and economic issues. Water withdrawals and pollution from agricultural, urban, and industrial sources have degraded water quality. Salinity, nutrients, fecal coliform bacteria, heavy metals, and toxic chemicals are concerns for river uses such as irrigation and drinking water. | |

| 32. Texas Blackland Prairies The Texas Blackland Prairies form a disjunct ecological region, distinguished from surrounding regions by fine-textured, clayey soils and predominantly prairie potential natural vegetation. The predominance of Vertisols in this area is related to soil formation in Cretaceous shale, chalk, and marl parent materials. Unlike tallgrass prairie soils that are mostly Mollisols in states to the north, this region contains Vertisols, Alfisols, and Mollisols. Dominant grasses included little bluestem, big bluestem, yellow Indiangrass, and switchgrass. This region now contains a higher percentage of cropland than adjacent regions; pasture and forage production for livestock is common. Large areas of the region are being converted to urban and industrial uses. Typical game species include mourning dove and northern bobwhite on uplands and eastern fox squirrel along stream bottomlands. | |

| 32a. The rolling to nearly level plains of the Northern Blackland Prairie ecoregion are underlain by interbedded chalks, marls, limestones, and shales of Cretaceous age. Soils are mostly fine-textured, dark, calcareous, and productive Vertisols. Historical vegetation was dominated by little bluestem, big bluestem, yellow Indiangrass, and tall dropseed. In lowlands and more mesic sites, such as on some of the clayey Vertisol soils in the higher precipitation areas to the northeast, dominant grasses were eastern gamagrass and switchgrass. Also in the northeast, over loamy Alfisols, were grass communities dominated by Silveanus dropseed, Mead’s sedge, bluestems, and long-spike tridens. Common forbs included asters, prairie bluet, prairie clovers, and black-eyed susan. Stream bottoms were often wooded with bur oak, Shumard oak, sugar hackberry, elm, ash, eastern cottonwood, and pecan. Most of the prairie has been converted to cropland, non-native pasture, and expanding urban uses around Dallas, Waco, Austin, and San Antonio. |

Less than one percent of the original vegetation remains in the Texas Blackland Prairies, scattered in several small parcels across the region. A transitional prairie type at the western edge of the region is shown here. These remnant prairies contain imperiled plant communities and provide habitat for many bird species and other fauna. Restoration activities in some of the protected prairies include prescribed burning, haying, and bison grazing. (Lee Stone, City of Austin) Less than one percent of the original vegetation remains in the Texas Blackland Prairies, scattered in several small parcels across the region. A transitional prairie type at the western edge of the region is shown here. These remnant prairies contain imperiled plant communities and provide habitat for many bird species and other fauna. Restoration activities in some of the protected prairies include prescribed burning, haying, and bison grazing. (Lee Stone, City of Austin)  Houston Black, recognized as the State Soil of Texas, is a Vertisol developed on the Texas Blackland Prairie. These clayey soils shrink when dry and swell when wet, and formed in calcareous clays and marls of Cretaceous age. These prime farmland soils are important agriculturally, supporting crops of grain sorghum, cotton, corn, small grains, and forage grasses. (Photo: NRCS) Houston Black, recognized as the State Soil of Texas, is a Vertisol developed on the Texas Blackland Prairie. These clayey soils shrink when dry and swell when wet, and formed in calcareous clays and marls of Cretaceous age. These prime farmland soils are important agriculturally, supporting crops of grain sorghum, cotton, corn, small grains, and forage grasses. (Photo: NRCS) |

| 32b. The Southern Blackland Prairie ecoregion, also known as the Fayette Prairie, has similarities to 32a, although there are some geologic, soil, vegetation, and land use differences. The Miocene-age Fleming Formation and to the west the Oakville Sandstone have some calcareous clays and marls, but differ some from the Cretaceous-age formations of Ecoregion 32a. Soils are mostly Vertisols (Calciusterts and Haplusterts), Mollisols (Calciustolls and Paleustolls), and Alfisols (Paleustalfs and Haplustalfs). The region appears more dissected than most of 32a, elevations are lower, and there are less extensive areas of cropland. Land cover is a more complex mosaic than in 32a, with more post oak woods and pasture. Historical grassland differences between 32b and 32a are not well known. Although they were likely to be generally similar, 32b may have had some subdominant species more similar to those of the Northern Humid Gulf Coastal Prairies (34a). Big bluestem was a likely dominant on the Blackland Prairie Mollisols, and little bluestem-brownseed paspalum prairie often occurred on the Fayette Prairie Alfisols. Similar to Ecoregion 32a, the shrink-swell clays contain gilgai microtopography with small knolls and shallow depressions that can influence the composition of plant communities. | |

| 32c. The Floodplains and Low Terraces ecoregion of the Texas Blackland Prairies includes only the broadest floodplains, i.e., those of the Trinity, Brazos, and Colorado rivers. It covers primarily the Holocene deposits and not the older, high terraces. The bottomland forests contained bur oak, Shumard oak, sugar hackberry, elm, ash, eastern cottonwood, and pecan, but most have been converted to cropland and pasture. The alluvial soils include Vertisols, Mollisols, and Inceptisols. | |

| 33. East Central Texas Plains Also called the Post Oak Savanna or the Claypan Area, this region of irregular plains was originally covered by post oak savanna vegetation, in contrast to the more open prairie-type regions to the north, south, and west, and the pine forests to the east. The boundary with Ecoregion 35 is a subtle transition of soils and vegetation. Soils are variable among the parallel ridges and valleys, but tend to be acidic, with sands and sandy loams on the uplands and clay to clay loams in low-lying areas. Many areas have a dense, underlying clay pan affecting water movement and available moisture for plant growth. The bulk of this region is now used for pasture and range. | |

| 33a. The landscapes of the Northern Post Oak Savanna ecoregion are generally more level and gently rolling compared to the more dissected and irregular topography of much of Ecoregion 33b to the south. It is underlain by mostly Eocene and Paleocene-age formations with some Cretaceous rocks to the north. The soils have an udic soil moisture regime compared to ustic in Ecoregion 33b to the south, and are generally finer textured loams. Annual precipitation averages 40-48 inches compared to 28-40 inches in Ecoregion 33b. The deciduous forest or woodland is composed mostly of post oak, blackjack oak, eastern redcedar, and black hickory. Prairie openings contained little bluestem and other grasses and forbs. The land cover currently has more improved pasture and less post oak woods and forest than 33b. Some coniferous trees occur, especially on the transitional boundary with Ecoregion 35a. Loblolly pine has been planted in several areas. Typical wildlife species include white-tailed deer, eastern wild turkey, northern bobwhite, eastern fox squirrel, and eastern gray squirrel. |

|

| 33b. The Southern Post Oak Savanna ecoregion has more woods and forest than the adjacent prairie ecoregions (32 and 34), and consists of mostly hardwoods compared to the pines to the east in Ecoregion 35. Historically a post oak savanna, current land cover is a mix of post oak woods, improved pasture, and rangeland, with some invasive mesquite to the south. A thick understory of yaupon and eastern redcedar occurs in some parts. Many areas of this region have more dissected and irregular topography than Ecoregion 33a to the north. The soils generally have an ustic soil moisture regime compared to udic in Ecoregion 33a, and more sand and sandy loam surface textures. It is underlain by Miocene, Oligocene, Eocene, and Paleocene sediments. Sand exposures within these Tertiary deposits have a distinctive sandyland flora, and in a few areas unique bogs occur. | |

| 33c. The San Antonio Prairie is a narrow, 100-mile long region occurring primarily on the Eocene Cook Mountain Formation. Soils of Ecoregion 33c are mostly Alfisols, with some Vertisols, and Mollisols. Generally, there are fewer Vertisols compared to the Northern Blackland Prairie ecoregion (32a) to the west. Upland Alfisol prairies were dominated by little bluestem and yellow Indiangrass and contained a different mix of grasses and forbs than the dark, clayey, more calcareous Vertisols of Ecoregion 32a. Since the 1830’s, settlement clustered along the Old San Antonio Road (State Highway 21 in the south, Old San Antonio Road in the north) within this narrow belt of prairie land. Currently, land cover is a mosaic of woodland, improved pasture, rangeland, and some cropland. | |

| 33d. The small, disjunct areas of the Northern Prairie Outliers ecoregion have a blend of characteristics from Ecoregions 32 and 33. The northern two outliers, north of the Sulphur River, occur on Cretaceous sediments, while south of the river, Paleocene and Eocene formations predominate. A mosaic of forest and prairie occurred historically in this and adjacent regions. Burning was important in maintaining grassy openings, and woody invasions have taken place in the absence of fire. The tallgrass prairies included little bluestem, big bluestem, yellow Indiangrass, and tall dropseed. Current land cover is mostly pasture, with some cropland. | |

| 33e. The Bastrop Lost Pines ecoregion is an outlier of relict loblolly pine-post oak upland forest occurring on some dissected hills. It is the westernmost tract of southern pine in the United States. The pines mostly occur on gravelly soils that formed in Pleistocene high gravel, fluvial terrace deposits associated with the ancestral Colorado River, and sandy soils that formed in Eocene sandstones (Sparta Sand, Weches Formation, Queen City Sand, Recklaw Formation, and Carrizo Sand). The Lost Pines are about 100 miles west of the Texas pine belt of Ecoregion 35 and occur in a drier environment with 36 inches of average annual precipitation. In this area, the deep, acidic, sandy soils and the additional moisture provided by the Colorado River contribute to the occurrence of pines, which are thought to be a relict population predating the last glacial period. Other areas of loblolly pines appear within parts of 33b, but are mostly too small to map at this scale. | |

| 33f. The Floodplains and Low Terraces ecoregion contains floodplain and low terrace deposits downstream from Ecoregion 32 and upstream from Ecoregions 34 and 35. It includes only the wider floodplains of major streams, such as the Sulphur, Trinity, Brazos, and Colorado rivers. In addition, it covers primarily Holocene deposits and not Pleistocene deposits on older, high terraces. The bottomland forests contain water oak, post oak, elms, green ash, pecan, willow oak to the east, and to the west some hackberry and eastern cottonwoods. The northern floodplains tend to have more forested land cover, while in the south the Brazos and Colorado River floodplains are characterized by more cropland and pasture. | |

| 34. Western Gulf Coastal Plains The principal distinguishing characteristics of the Western Gulf Coastal Plain are its relatively flat topography and mainly grassland potential natural vegetation. Inland from this region the plains are older, more irregular, and have mostly forest or savanna-type vegetation potentials. Largely because of these characteristics, a higher percentage of the land is in cropland than in bordering ecological regions. Rice, grain sorghum, cotton, and soybeans are the principal crops. Urban and industrial land uses have expanded greatly in recent decades, and oil and gas production is common. | |

| 34a. Quaternary-age deltaic sands, silts, and clays underlie much of the Northern Humid Gulf Coastal Prairies on this gently sloping coastal plain. The original vegetation was mostly grasslands with a few clusters of oaks, known as oak mottes or maritime woodlands. Little bluestem, yellow Indiangrass, brownseed paspalum, gulf muhly, and switchgrass were the dominant grassland species, with some similarities to the grasslands of Ecoregion 32. Almost all of the coastal prairies have been converted to cropland, rangeland, pasture, or urban land uses. The exotic Chinese tallow tree and Chinese privet have invaded large areas in this region. Some loblolly pine occurs in the northern part of the region in the transition to Ecoregion 35. Soils are mostly fine-textured: clay, clay loam, or sandy clay loam. Within the region, there are some differences from the higher Lissie Formation to the lower Beaumont Formation, both of Pleistocene age. The Lissie Formation has lighter colored soils, mostly Alfisols with sandy clay loam surface texture, while darker, clayey soils associated with Vertisols are more typical of the Beaumont Formation. Annual precipitation varies from 37 inches in the southwest portion to 58 inches in the northeast, with a summer maximum. |

Barrier islands, peninsulas, bays, lagoons, marshes, estuaries, and flat plains characterize Ecoregion 34. The region has been greatly modified. About 35 percent of the state’s population and a large part of its industrial base, commerce, and jobs are located within 100 miles of the coastline. More than half of the United States’ chemical and petroleum production is located on the Texas coast. (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers) Barrier islands, peninsulas, bays, lagoons, marshes, estuaries, and flat plains characterize Ecoregion 34. The region has been greatly modified. About 35 percent of the state’s population and a large part of its industrial base, commerce, and jobs are located within 100 miles of the coastline. More than half of the United States’ chemical and petroleum production is located on the Texas coast. (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers) |

| 34b. The Southern Subhumid Gulf Coastal Prairies ecoregion is drier than Ecoregion 34a to the north, not only receiving less annual precipitation, but also typically experiencing summer drought. Annual precipitation ranges from 26 inches in the southwest to 37 inches in the northeast, with May and September peaks. Soils are hyperthermic compared to thermic in most of Ecoregion 34a. Little bluestem, yellow Indiangrass, and tall dropseed were once dominant grasses. Eragrostoid grasses, including the genera Bouteloua, Buchloe, Eragrostis, Hilaria, and Setaria increase in importance in Ecoregion 34b compared to 34a. Invasive species such as honey mesquite and huisache are a concern. Within the region, there are some differences from the higher Lissie Formation to the lower Beaumont Formation, both of Pleistocene age. The Lissie Formation has lighter colored soils, mostly Alfisols with sandy clay loam surface texture, while darker, clayey Vertisols are more typical of the Beaumont Formation. Almost all of the coastal prairies have been converted to other land uses: cropland, pasture, or urban and industrial. | |

| 34c. Covering primarily the Holocene floodplain and low terrace deposits, the Floodplains and Low Terraces ecoregion, especially to the southwest, has a different bottomland forest than the floodplains of Ecoregion 35. Bottomland forests of pecan, water oak, southern live oak, and elm, are typical, with some baldcypress on larger streams. The Brazos and Colorado River floodplains are a broad expanse of alluvial sediments, while floodplains to the south are more narrow. Soils include Vertisols, Mollisols, and Entisols. Large portions of floodplain forest have been removed and land cover is now a mix of forest, cropland, and pasture. | |

| 34d. The Coastal Sand Plain ecoregion provides a distinct break in both vegetation and surficial materials from the fine-textured soil grasslands of Ecoregion 34b to the north. This sand sheet landscape consists of active and (mostly) stabilized sand dune deposits with lesser amounts of silt sheet deposits (silt and fine sand) to the north. This depositional plain is characterized by a closed internal drainage system with only occasional discontinuous drainage remnants due to sand movement. Closed depressions pond water in response to seasonal and tropical storm precipitation. Soils developed on these parent sediments are Entisols and Alfisols with thick sand surfaces. The dominant grasses on the coastal sand ridges and islands extend inland covering parts of the sand plain. Vegetation is mostly mid and tall grasses such as seacoast bluestem, switchgrass, gulfdune paspalum, fringeleaf paspalum, sandbur, purple threeawn, pricklypear, and catclaw with an overstory of southern live oak and honey mesquite trees. The potholes have a variety of bulrushes and sedges. Most of the Coastal Sand Plain has been moderately to heavily grazed, and large areas have been converted to non-native range or pasture grasses. The region has little cropland compared to Ecoregion 34b. | |

| 34e. The Lower Rio Grande Valley ecoregion once supported dense, diverse grassland and shrub communities and low woodlands. However, mesquite, granjeno, and a variety of brush and shrub species invaded the landscape. Now, it is almost all in cropland, pasture, and urban land cover. The region is underlain by a mix of Quaternary clays and sands with some Miocene-age sediments of the Goliad Formation at the western edge. Mollisols are extensive, and the soils are deep, mostly clay loams and sandy clay loams. The freeze-free growing season is often over 320 days compared to 250-260 days along the northern Texas coastal area of Ecoregion 34a. Along with Ecoregion 34f, the Lower Rio Grande Valley contains important nesting grounds for the white-winged dove, a favored hunting species in southern Texas. | |

| 34f. The Lower Rio Grande Alluvial Floodplain ecoregion includes the Holocene-age alluvial sands and clays of the Rio Grande floodplain that are now almost completely in cropland or urban land cover. The soils, mostly Vertisols and Mollisols, are deep, loamy and clayey, and tend to be finer-textured than in Ecoregion 34e to the north. Some Entisols and Inceptisols occur near the river. The floodplain ridges once had abundant palm trees, and early Spanish explorers called the river “Rio de las Palmas.” Most large palm trees and floodplain forests had been cleared by the early 1900’s. A few small pieces of unique floodplain forests remain, including Texas ebony, Texas palmetto, and sugar hackberry-cedar elm floodplain forests. It is the most subtropical climate of Texas, but hard freezes occasionally occur, affecting plants and animals that are at the northern limit of their range. Crops include cotton, citrus, grain sorghum, sugar cane, vegetables, and melons. The Rio Grande’s water is mostly diverted from its channel for irrigation and urban use, and little or no flow reaches the Gulf of Mexico. Both the Central and Mississippi flyways funnel through the southern tip of Texas and many species of birds reach their extreme northernmost range in this region. In addition, subtropical, temperate, coastal, and desert influences converge here, allowing for great species diversity. Nearly 500 bird species, including neotropical migratory birds, shorebirds, raptors, and waterfowl, can be found here. | |

| 34g. The Texas-Louisiana Coastal Marshes region is distinguished from Ecoregions 34h and 34i by its extensive freshwater and saltwater coastal marshes, lack of barrier islands and fewer bays, and its wetter, more humid climate. Annual precipitation is 48 to 54 inches in Texas and up to 60 inches in Louisiana. There are many rivers, lakes, bayous, tidal channels, and canals. The streams and rivers that supply nutrients and sediments to this region are primarily from the humid pine belt of Ecoregion 35. Extensive cordgrass marshes occur. The estuarine and marsh complex supports marine life, supplies wintering grounds for ducks and geese, and provides habitat for small mammals and American alligators. Brown shrimp, the most commercially important marine species in Texas, is common along the whole coast, but in this northern coastal zone white shrimp are also commercially important. Eastern oysters and blue crabs are also common and commercially important in the region. Sport fishery species such as red drum, black drum, southern flounder, and spotted seatrout occur throughout the coastal bays of this region and Ecoregion 34h. | |

| 34h. The Mid-Coast Barrier Islands and Coastal Marshes portion of the Texas coast is subhumid compared to the humid climate of Ecoregion 34g to the northeast and to the semiarid climate of Ecoregion 34i to the south. Annual precipitation within Ecoregion 34h increases to the northeast, ranging from 34 to 46 inches. The region encompasses primarily Holocene deposits with saline, brackish, and freshwater marshes, barrier islands with minor washover fans, and tidal flat sands and clays. In the inland section from Matagorda Bay to Corpus Christi Bay, Pleistocene barrier island deposits occur. Typical soils on the coastal marshes are Entisols, with a minor extent of Histosols. Mollisols occur on tidal flats and coastal marshes, and Entisols form in sandy barrier islands and dunes. Smooth cordgrass, marshhay cordgrass, and gulf saltgrass dominate in more saline zones. Other native vegetation is mainly grassland composed of seacoast bluestem, sea-oats, common reed, gulfdune paspalum, and soilbind morning-glory. Some areas have clumps of sweetbay, redbay, and dwarf southern live oak trees. In the Coastal Bend area, the barrier islands support extensive foredunes and back-island dune fields. Scarps can characterize bay margins due to beach erosion. Salt marsh and wind-tidal flats are mostly confined to the back side of the barrier islands with fresh or brackish marshes associated with river-mouth delta areas. Marshhay cordgrass becomes less important to the south in this region. Black mangrove begins to appear from Port O'Connor south. This area of the coast has all three commercially important species of shrimp as well as important oyster and blue crab fisheries. Convergence of longshore currents from north and south occurs south of the Corpus Christi area near Padre Island National Seashore. Corpus Christi Bay serves as the ecozone or boundary between two distinct estuarine ecosystems. Copano and Mesquite bays to the north are low to moderate-salinity bays and attract whooping cranes and other birdlife. To the south in 34i, hypersaline Laguna Madre forms a unique ecosystem and supports greater expanses of seagrasses. | |

| 34i. The Laguna Madre Barrier Islands and Coastal Marshes ecoregion is distinguished by its hypersaline lagoon system, vast seagrass meadows, wide tidal mud flats, large overwintering redhead duck population, numerous protected species, great fishery productivity, and a narrow barrier island with a number of washover fans. The lower coastal zone in Texas has a more semi-arid climate and has less precipitation (27-29 inches) compared to 34g and 34h. There is extreme variability in annual rainfall, and evapotranspiration is generally two to three times greater than precipitation. As no rivers drain into the Texas Laguna Madre, the lagoon water can be hypersaline. Combined with the Laguna Madre of Tamaulipas, it is the largest hypersaline system in the world. The shallow depth, clear water, and warm climate of this lagoon are conducive to seagrass production. Nearly 80% of all seagrass beds in Texas are now found in the Laguna Madre. The food web of the Laguna Madre is predominantly based on this submerged aquatic vegetation (seagrass and algae), rather than free-floating phytoplankton. Because of the hypersalinity, oysters are not commercially harvested to a large extent, although the region does contain the only strain of high-salinity adapted oysters in North America. The blue crab harvest is also smaller than the other two coastal regions to the north. Pink shrimp make up an important part of the commercial harvest while white shrimp are more abundant to the north in 34g. The historically highly productive commercial fisheries have now given way to an important sport fishery for species such as red drum, black drum, and spotted sea trout. Marshes are less extensive on the southern coast. A few stands of black mangrove tidal shrub occur in this region. | |

| 35. South Central Plains Locally termed the “piney woods”, this region of mostly irregular plains represents the western edge of the southern coniferous forest belt. Once blanketed by a mix of pine and hardwood forests, much of the region is now in loblolly and shortleaf pine plantations. Soils are mostly acidic sands and sandy loams. Covering parts of Louisiana, Arkansas, east Texas, and Oklahoma, only about one sixth of the region is in cropland, primarily within the Red River floodplain, while about two thirds of the region is in forests and woodland. Lumber, pulpwood, oil, and gas production are major economic activities. | |

| 35a. The rolling Tertiary Uplands, gently to moderately sloping, cover a large area in east Texas, southern Arkansas, and northern Louisiana. In East Texas, Tertiary deposits are mostly Eocene sediments, with minor amounts of Paleocene and Cretaceous sediments in the north. Soils are mostly well-drained Ultisols and Alfisols, typically with sandy and loamy surface textures. Natural vegetation includes loblolly pine, shortleaf pine, southern red oak, post oak, white oak, hickory, and sweetgum, and mid and tall grasses such as yellow Indiangrass, pinehill bluestem, narrowleaf woodoats, and panicums. American beautyberry, sumac, greenbriar, and hawthorn are part of the understory. The sandier areas, mostly found on the Sparta, Queen City, and Carrizo Sand Formations, often have more bluejack oak, post oak, and stunted pines. Pine density is less than in Ecoregions 35e and 35f to the south and in 35a to the east in Arkansas and Louisiana. Toward the western boundary, this region is slightly drier and has more pasture, oak-pine, and oak-hickory forest compared to other regions of Ecoregion 35. Many areas are replanted to loblolly pine for timber production, or are in improved pasture. Lumber and pulpwood production, livestock grazing, and poultry production are typical land uses. Oil and gas production is also widespread. |

|

| 35b. In Texas, the Floodplains and Low Terraces of Ecoregion 35 comprise the western margin of the southern bottomland hardwood communities that extend along the Gulf and Atlantic coastal plains from Texas to Virginia. As delineated, 35b is mostly the Holocene alluvial floodplains and low terraces where there is a distinct vegetation change into bottomland oaks and gum forest. It does not include all of the higher terraces such as the older Deweyville Formation terraces where vegetation tends to be more similar to the uplands, with some minor swamp and wetland communities. Water oak, willow oak, sweetgum, blackgum, elm, red maple, southern red oak, swamp chestnut oak, and loblolly pine are typical. Baldcypress and water tupelo occur in semipermanently flooded areas. Soils can include Inceptisols, Vertisols, and Entisols and are generally somewhat poorly drained to very poorly drained, clayey and loamy. | |

| 35c. The Pleistocene Fluvial Terraces ecoregion covers significant terrace deposits on major streams in Louisiana and Arkansas, but terraces are less extensive in Texas, occurring mostly along the Red River. Some smaller terraces occur along the Sulphur River but are not mapped at this scale. The broad flats and gently sloping stream terraces are lower and less dissected than 35a, but higher than the floodplains of 35b. Soils are typically Alfisols. In Texas, current land cover is mostly pine-hardwood forest, with post oak, Shumard oak, and eastern redcedar woods to the west. In Arkansas, loblolly pine is more common on the terraces than shortleaf pine. | |

| 35e. The Southern Tertiary Uplands ecoregion generally covers the remainder of longleaf pine range north of the Flatwoods (35f) on Tertiary sediments. Longleaf pine often occurred on sand ridges and uplands, but open forests were also found on other soil types and locations in 35e and 35f. On more mesic sites, some American beech or magnolia-beech-loblolly pine forests occurred. Some sandstone outcrops (Catahoula Formation) have distinctive barrens or glades in Texas and Louisiana. Seeps in sand hills support acid bog species including southern sweetbay, hollies, wax-myrtles, insectivorous plants, orchids, and wild azalea; this vegetation becomes more extensive in the Flatwoods (35f). The region is more hilly and dissected than the Flatwoods (35f) to the south, and soils are generally better drained over the more permeable sediments. Currently, it has more pine forest than the oak-pine and pasture land cover to the north in 35a. Large parts of the region are public National Forest land. | |