Ecoregions of Arkansas (EPA)

Overlooking the Ouachita Mountains from Hot Springs Mountain Tower, Hot Springs National Park, Hot Springs, Arkansas. (By Ken Lund from Las Vegas, Nevada, USA (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0), via Wikimedia Commons)

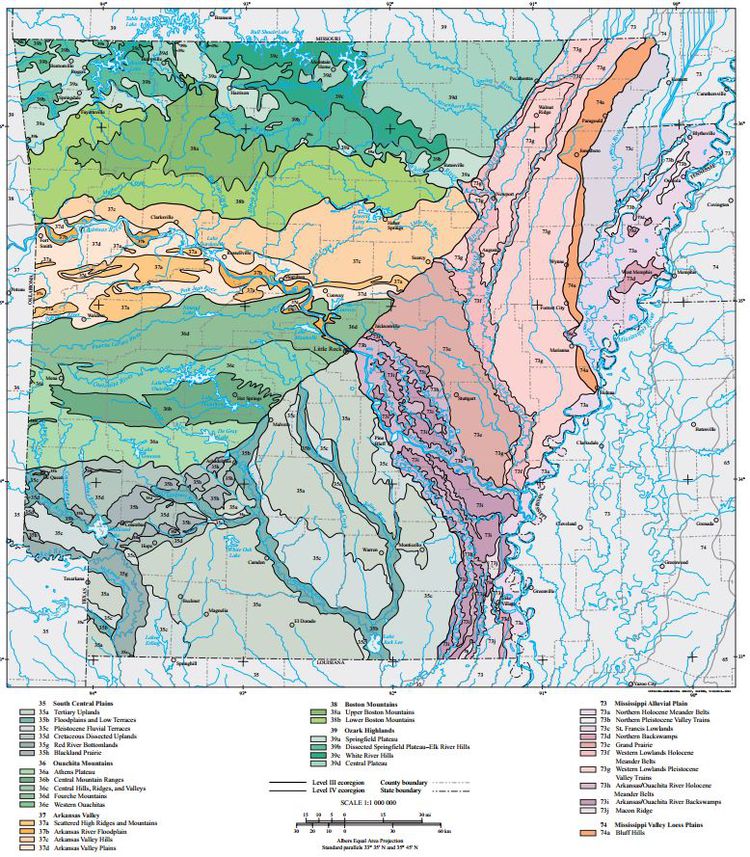

Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, and quantity of environmental resources. They are designed to serve as a spatial framework for the research, assessment, management, and monitoring of ecosystems and ecosystem components. By recognizing the spatial differences in the capacities and potentials of ecosystems, ecoregions stratify the environment by its probable response to disturbance (Bryce, Omernik, and Larsen, 1999).

Ecoregions are general purpose regions that are critical for structuring and implementing ecosystem management strategies across federal agencies, state agencies, and nongovernment organizations that are responsible for different types of resources in the same geographical areas (Omernik and others, 2000). A Roman numeral hierarchical scheme has been adopted for different levels of ecological regions. Level I (Ecoregions of Arkansas (EPA)) is the coarsest level, dividing North America into 15 ecological regions. Level II (Ecoregions of Arkansas (EPA)) divides the continent into 52 regions (Commission for Environmental Cooperation Working Group, 1997). At Level III (Ecoregions of Arkansas (EPA)), the continental United States contains 104 ecoregions and the conterminous United States has 84 ecoregions (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency [USEPA], 2003). Level IV (Ecoregions of Arkansas (EPA)) ecoregions are further subdivisions of level III ecoregions. Explanations of the methods used to define the USEPA’s ecoregions are given in Omernik (1995), Omernik and others (2000), and Gallant and others (1989).

The approach used to compile the ecoregion map of Arkansas is based on the premise that ecological regions can be identified through the analysis of the spatial patterns and the composition of biotic and abiotic characteristics that affect or reflect differences in ecosystem quality and integrity (Wiken, 1986; Omernik, 1987, 1995). These characteristics include geology, physiography, climate, soils, land use, wildlife, fish, hydrology, and vegetation (including “potential natural vegetation” defined by Küchler (p. 2, 1964) as “vegetation that would exist today" if human influence ended and "the resulting plant succession" was "telescoped into a single moment”). The relative importance of each characteristic varies from one ecological region to another regardless of ecoregion hierarchical level.

In Arkansas, there are 7 level III ecoregions and 32 level IV ecoregions; all but four level IV ecoregions continue into ecologically similar parts of adjacent states (Chapman and others, 2002, 2004a, 2004b; Griffith, Omernik, and Azevedo, 1998). Arkansas’ ecological diversity is strongly related to regional physiography, geology, soil, climate, and land use. Elevated karst plateaus, folded mountains, agricultural valleys, forested uplands, and bottomland forests occur. Fire-maintained prairie was once extensive in several parts of the state.

The ecoregion map on this poster was compiled at a scale of 1:250,000, and depicts revisions and subdivisions of earlier level III ecoregions that were originally compiled at a smaller scale (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2003; Omernik, 1987). It is part of a collaborative project primarily between USEPA Region 6, USEPA–National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory (Corvallis, OR.), and the Multi-Agency Wetland Planning Team (MAWPT), which comprises representatives of six Arkansas state agencies (Arkansas Natural Heritage Commission, Arkansas Soil and Water Conservation Commission, Arkansas Game and Fish Commission, Arkansas Department of Environmental Quality, Arkansas Forestry Commission, and University of Arkansas Cooperative Extension Service). Collaboration and consultation also occurred with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), U.S. Department of Agriculture–Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), U.S. Geologic Survey (USGS), U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, USGS–Earth Resources Observation Systems Data Center, and University of Arkansas–Center for Advanced Spatial Technologies.

This project is associated with an interagency effort to develop a common framework of ecological regions (McMahon and others, 2001). Reaching that objective requires recognition of the differences in the conceptual approaches and mapping methodologies applied to develop the most common ecoregion-type frameworks, including those developed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture–Forest Service (Bailey and others, 1994), the USEPA (Omernik 1987, 1995), and the U.S. Department of Agriculture–Soil Conservation Service (1981). As each of these frameworks is further refined, their differences are becoming less discernible. Each collaborative ecoregion project, such as this one in Arkansas, is a step toward attaining consensus and consistency in ecoregion frameworks for the entire nation.

|

35. South Central Plains | |

|

35a. The rolling Tertiary Uplands are dominated by commercial pine plantations that have replaced the native oak– hickory–pine forest. Ecoregion 35a is underlain by poorly-consolidated Tertiary sand, silt, and gravel; it lacks the Cretaceous, often calcareous rocks of Ecoregion 35d and the extensive Quaternary alluvium of Ecoregions 35b, 35g, and 73. Extensive forests dominated by loblolly and shortleaf pines grow on loamy, well-drained, thermic Ultisols; scattered, stunted, sandhill woodlands also occur. Waters tend to be stained by organics, thus lowering water clarity and increasing total organic carbon and biochemical oxygen demand levels. Most streams have a sandy substrate and a forest canopy. Many do not flow during the summer or early fall. However, in sandhills, spring-fed, perennial streams occur; here, total dissolved solids, total suspended solids, alkalinity, and hardness values are lower than elsewhere in Ecoregion 35. Water quality in forested basins is better than in pastureland. Oil production has lowered stream quality in the south. |

The rolling Tertiary Uplands (35a) are widely covered by trees and are underlain by both coastal plain and marginal marine deposits. The poorly consolidated nature of these deposits allows even small streams to carve relatively wide bottomlands. Dorcheat Bayou, which flows through Falcon Bottoms Natural Area northeast of Buckner, is pictured here. Dorcheat Bayou is considered to be The rolling Tertiary Uplands (35a) are widely covered by trees and are underlain by both coastal plain and marginal marine deposits. The poorly consolidated nature of these deposits allows even small streams to carve relatively wide bottomlands. Dorcheat Bayou, which flows through Falcon Bottoms Natural Area northeast of Buckner, is pictured here. Dorcheat Bayou is considered to beone of Arkansas’ most intact and ecologically important streams in Ecoregion 35 west of the Ouachita River. Pine flatwoods are found adjacent to bottoms. Better drained sites, including knolls, support upland pine–hardwood forest. (Photo: Thomas L. Foti, Arkansas Natural Heritage Commission) |

|

36. Ouachita Mountains | |

|

36a. The low ridges and hills of the Athens Plateau are widely underlain by shale in contrast to other parts of Ecoregion 36. Rocks are less resistant to erosion than in higher, more rugged Ecoregions 36b, 36d, and 36e but are more resistant than the unconsolidated rocks of the coastal plain in Ecoregion 35. Today, pine plantations are widespread; they are far more extensive than in the more rugged parts of Ecoregion 36 in Arkansas. Pastureland and hayland also occur. Cattle and broiler chickens are important farm products. Water quality values are distinct from Ecoregion 36c. |

|

|

37. Arkansas Valley | |

| 37a. The Scattered High Ridges and Mountains ecoregion is more rugged and wooded than Ecoregions 37b, 37c, or 37d. Ecoregion 37a is characteristically covered by savannas, open woodlands, or forests dominated or codominated by upland oaks, hickory, and shortleaf pine; loblolly pine occurs but is not native. It is underlain by Pennsylvanian sandstone and shale; calcareous rocks such as those that dominate the Ozark Highlands (39) are absent. Nutrient and mineral values (including turbidity and hardness) in streams are slightly higher than in other parts of the Arkansas Valley (37). Magazine Mountain, the highest point in Arkansas at 2,753 feet, is distinguished by diverse habitats. Its flat top is covered with xeric, stunted woodlands. Mesic sites also occur and may contain beech–maple forests. 37b. The Arkansas River Floodplain is characteristically veneered with Holocene alluvium and includes natural levees, meander scars, oxbow lakes, point bars, swales, and backswamps. It is lithologically and physiographically distinct from the surrounding uplands of the Arkansas Valley (37). Mollisols, Entisols, Alfisols, and Inceptisols are common; the soil mosaic sharply contrasts with nearby, higher elevation ecoregions where Ultisols developed under upland oaks, hickory, and pine. Potential natural vegetation is southern floodplain forest. Bottomland oaks including bur oak, American sycamore, sweetgum, willows, eastern cottonwood, green ash, pecan, hackberry, and elm were once extensive. They have been widely cleared for pastureland, hayland, and cropland. However, some forest remains in frequently flooded or poorly-drained areas. In Arkansas, bur oak is most dominant in Ecoregion 37b. 37c. The Arkansas Valley Hills are underlain by Pennsylvanian sandstone and shale, and are lithologically distinct from Ecoregions 37b and 39. Ecoregion 37c is more hilly than the Arkansas Valley Plains (37d) and less rugged than Ecoregions 36, 37a, and 38. Ultisols are common and support a potential natural vegetation of oak–hickory forest or oak–hickory–pine forest; both soils and natural vegetation contrast with those of Ecoregion 37b. Today, pastureland is extensive, but rugged areas are wooded; overall, trees are much less extensive than in neighboring Ecoregions 36d, 37a, and 38 but more widespread than in Ecoregions 37b and 37d. Poultry operations, livestock farming, and logging are important land uses. 37d. The Arkansas Valley Plains are in the rainshadow of the Fourche Mountains and were once covered by a distinctive mosaic of prairie, savanna, and woodland. Ecoregion 37d is mostly undulating but a few hills and ridges occur. Westward, Ecoregion 37d becomes flatter, drier, more open, and has fewer topographic fire barriers. Prior to the 19th century, frequently burned western areas had extensive prairie on droughty soils; scattered pine–oak savanna also occurred. Elsewhere, potential natural vegetation is primarily oak–hickory forest or oak–hickory–pine forest. Today, pastureland and hayland are extensive but remnants of prairie, particularly the Cherokee Prairie near Fort Smith, and woodland occur. Poultry and livestock farming are primary land uses. Cropland agriculture in the Arkansas Valley Plains (37d) is less important than in Ecoregion 37b, and wooded areas are not as extensive as in more rugged Ecoregions 36, 37a, 37c, and 38. Stream turbidity generally remains low except during storm events. |

|

| 38. Boston Mountains Ecoregion 38 is mountainous, forested, and underlain by Pennsylvanian sandstone, shale, and siltstone. It is one of the Ozark Plateaus; some folding and faulting has occurred but, in general, strata are much less deformed than in the Ouachita Mountains (36). Maximum elevations are higher, soils have a warmer temperture regime, and carbonate rocks are much less extensive than in the Ozark Highlands (39). Physiography is distinct from the Arkansas Valley (37). Upland soils are mostly Ultisols that developed under oak–hickory and oak–hickory–pine forests. Today, forests are still widespread; northern red oak, southern red oak, white oak, and hickories usually dominate the uplands, but shortleaf pine grows on drier, south- and west-facing slopes underlain by sandstone. Pastureland or hayland occur on nearly level ridgetops, benches, and valley floors. Population density is low; recreation, logging, and livestock farming are the primary land uses. Water quality in streams is generally exceptional; biochemical, nutrient, and mineral water quality parameter concentrations all tend to be very low. Fish communities are mostly composed of sensitive species; a diverse, often darter-dominated community occurs along with nearly equal proportions of minnows and sunfishes. During low flows, streams in both Ecoregions 38 and 36 usually run clear but, during high flow conditions, turbidity in Ecoregion 38 tends to be greater than in Ecoregion 36. Summer flow in many small streams is limited or non-existent but isolated, enduring pools may occur. | |

|

38a. The Upper Boston Mountains ecoregion is generally higher and moister than the Lower Boston Mountains (38b); elevations vary from 1,900 to 2,800 feet. Potential natural vegetation is oak–hickory forest. Characteristically, the forests of the Upper Boston Mountains (38a) are more closed and contain far less pine than those of the Lower Boston Mountains (38b). North-facing slopes support mesic forests. Ecoregion 38a is underlain by Pennsylvanian sandstone, shale and siltstone that contrasts with the limestone and dolomite that dominates Ozark Highlands (39). Water quality in streams reflects geology, soils, and land use, and is typically exceptional; mineral, nutrient, and solid concentrations as well as turbidity all tend to be very low. During the summer, many streams do not flow. |

|

| 39. Ozark Highlands The Ozarks formed as the Ouachita Mountains weighted down the edge of the North American continent, flexing the crust of the Arkoma Basin upward; younger sedimentary layers then eroded away, exposing the older, Paleozoic rocks that dominate the area. Ecoregion 39 is composed of the Springfield and Salem plateaus and largely underlain by highly soluble and fractured limestone and dolomite. It is level to highly dissected, partly forested, and rich in karst features. Caves, sinkholes, and underground drainage occur, heavily influencing surficial water availability and water temperature. Clear, cold, perennial, spring-fed streams are common, and typically have gravelly substrates; in addition, many small dry valleys occur. Ecoregion 39 is not as mountainous as Ecoregions 36 or 38, but is higher and more rugged than Ecoregion 73. Habitat diversity and species richness is high. Soils are often cherty and have developed from carbonate rocks or interbedded chert, sandstone, and shale; mesic Ultisols, Alfisols, and Mollisols are common. Soil order mosaic, soil temperature regime, and lithology are all distinct from nearby Ecoregions 36, 37, 38, and 73. Potential natural vegetation is mostly oak–hickory forest. Open forest dominates rugged areas and pastureland and hayland are common on nearly level sites. Shortleaf pine grows on steep, cherty escarpments and on shallow soils derived from sandstone; it becomes more common in Ecoregions 35, 36, and the southern portion of Ecoregion 38. Glades dominated by grass and eastern redcedar are found on shallow, droughty soils especially over dolomite. Primary land uses are logging, housing, recreation, and, especially, poultry and livestock farming. Water quality in the Ozark Highlands (39) is different from the other ecoregions in Arkansas and is strongly influenced by lithology and land use practices. Alkalinity, total dissolved solids, and total hardness values are relatively high, reflecting the influence of Ecoregion 39’s distinctive limestone and dolomite. Fecal coliform and nitrite-nitrate values are elevated downstream of improved pastureland that is intensively grazed by cattle and fields where animal wastes from confined poultry and hog operations have been applied. Parts of Ecoregion 39 are experiencing rapid population growth along with associated habitat alteration and water pollution. Fish communities characteristically have a preponderance of sensitive species and are usually dominated by a diverse minnow community along with sunfishes and darters. | |

| 39a. The nearly level to rolling Springfield Plateau is underlain by cherty limestone of the Mississippian Boone Formation; it is less rugged and wooded than Ecoregions 38, 39b, and 39c, and lacks the Ordovician dolomite and limestone of Ecoregions 39c and 39d. Karst features, such as sinkholes and caves, are common. Cold, perennial, spring-fed streams occur. Upland potential natural vegetation is primarily oak–hickory and also oak–hickory–pine forests; savannas and tall grass prairies also occurred and were maintained by fire. Today, most of the forest and almost all of the prairie have been replaced by agriculture or expanding residential areas. Poultry, cattle, and hog farming are primary land uses; pastureland and hayland are common. Application of poultry litter to agricultural fields is a non-point source that can impair water quality. Total suspended solids and turbidity values in streams are usually low, but total dissolved solids and hardness values are high. 39b. The Dissected Springfield Plateau–Elk River Hills are underlain by cherty limestone of the Mississippian Boone Formation and contain many karst features. Cold, perennial, spring-fed streams occur. Ecoregion 39b is more rugged and wooded than the lithologically similar Springfield Plateau (39a) and the lithologically dissimilar Central Plateau (39d). Potential natural vegetation is oak–hickory and oak–hickory–pine forests. Shortleaf pine grows on the thin, cherty soils of steep slopes, and is more common than in Ecoregion 39a, 39c, and 39d. Scattered limestone glades occur, but are less extensive than on the dolomites of the lithologically distinct Ecoregion 39c. Today, Ecoregion 39b remains dominated by forest and woodland. Logging, livestock farming, woodland grazing, recreation, quarrying, and housing are primary land uses. 39c. The forested White River Hills ecoregion is a highly dissected portion of the Salem Plateau that is underlain by cherty Ordovician dolomite and limestone. Soils are usually thin, rocky, steep, and nonarable. Flat land is uncommon except along the White River. Ecoregion 39c is lithologically unlike another highly dissected portion of the Ozarks, Ecoregion 39b, where Mississippian cherty limestone of the Boone Formation predominates. Clear, cold, perennial, spring-fed streams are common, but dry valleys occur. Potential natural vegetation is oak–hickory forest, oak–hickory–pine forest, and cedar glades. Glades are more extensive than elsewhere in Arkansas, and occur on thin, droughty soils derived from carbonates. Pine is most common on steep, thin, cherty soils. Ecoregion 39c includes Table Rock, Bull Shoals, Norfork, and Beaver lakes. Turbidity and total suspended solids are usually low in its streams and rivers, but total dissolved solids and hardness values are high. 39d. The Central Plateau is an undulating to hilly portion of the Salem Plateau that is dominated by agriculture. Ecoregion 39d is largely underlain by cherty Ordovician dolomite and limestone; it is lithologically distinct from another slightly dissected part of the Ozarks, the Springfield Plateau (39a). Karst features occur. The Central Plateau (39d) is less rugged and wooded than Ecoregions 38, 39b, and 39c. Natural vegetation is oak–hickory forest, oak–hickory–pine forest (often on soils derived from sandstone), barrens (on thin soils), and scattered cedar glades (on shallow, rocky, droughty soils from dolomite or limestone). Today, pastureland, hayland, and housing are common, but remnant forests and savannas occur in steeper areas. Turbidity, total suspended solids, total dissolved solids, and hardness values are often higher than in Ecoregions 39a and 39c. |

|

|

73. Mississippi Alluvial Plain | |

|

73a. The Northern Holocene Meander Belts ecoregion is a flat to nearly flat floodplain containing the meander belts of the present and past courses of the Mississippi River. Point bars, natural levees, swales, and abandoned channels marked by meander scars and oxbow lakes are common and characteristic. Ecoregion 73a tends to be slightly lower in elevation than adjacent ecoregions. Its abandoned channel network is more extensive than in the Southern Holocene Meander Belts (73k) of Louisiana. Ecoregion 73a is underlain by Holocene alluvium; it lacks the Pleistocene glacial outwash deposits of Ecoregion 73b. Soils on natural levees are relatively coarse-textured, well-drained, and higher than those on levee back slopes and point bars; they grade to very heavy, poorly-drained clays in abandoned channels and swales. Overall, soils are not as sandy as the Northern Pleistocene Valley Trains (73b) and are finer and have more organic matter than the Arkansas/Ouachita River Holocene Meander Belts (73h). Natural vegetation varies with site characteristics. Younger sandy soils have fewer oaks and more sugarberry, elm, ash, pecan, cottonwood, and sycamore than Ecoregion 73d. Widespread draining of wetlands and removal of bottomland forests for cropland has occurred. Soybeans, cotton, corn, sorghum, wheat, and rice are the main crops. Catfish farms are increasingly common and contribute to the already large agricultural base. |

|

| 74. Mississippi Valley Loess Plains Ecoregion 74 stretches from the Ohio River in western Kentucky all the way to Louisiana. It is characteristically veneered with windblown silt deposits (loess) and underlain by erosion-prone, unconsolidated coastal plain sediments; loess is thicker than in the Southeastern Plains (65). Western areas, including Arkansas, have hills, ridges, and bluffs, but further east in Mississippi and Tennessee, the topography becomes flatter. Overall, irregular plains are common. Ecoregion 74 is lithologically and physiographically distinct from the Ouachita Mountains (36), Boston Mountains (38), Ozark Highlands (39), Interior Plateau (71), and Interior River Valleys and Hills (72). Potential natural vegetation is primarily oak–hickory forest or oak–hickory–pine forest and is unlike the southern floodplain forests of the Mississippi Alluvial Plain (73). Streams tend to have gentler gradients and more silty substrates than in the Southeastern Plains (65). | |

|

74a. Crowley’s Ridge, the only portion of the Bluff Hills ecoregion in Arkansas, is a disjunct series of loess-capped hills surrounded by the lower, flatter Mississippi Alluvial Plain (73). Crowley’s Ridge, with elevations of up to 500 feet, is of sufficient height to have trapped wind-blown silt during the Pleistocene Epoch. It was formed by the aggregation of loess and the subsequent erosion by streams. The loess is subject to vertical sloughing when wet. Spring-fed streams and seep areas occur on the lower slopes and in basal areas where Tertiary sands and gravels, that were never removed by the Mississippi River, are exposed. Soils are generally well-drained; they are generally more loamy than those found in the surrounding Northern Pleistocene Valley Trains (73b) and St. Francis Lowlands (73c). Wooded land and pastureland are common; only limited cropland is found in Ecoregion 74a. Post oak–blackjack oak forest, southern red oak–white oak forest, and beech–maple forest occur. Undisturbed ravine vegetation can be rich in mesophytes, such as beech and sugar maple. Oaks still dominate most of these mesophytic communities. The forests of the Bluff Hills (74a) are usually classified as oak–beech. They are related to the beech–maple cove forests of the Appalachian Mountains; like the Appalachian cove forests, tulip poplar dominates early successional communities, at least in the southern ridge. In Arkansas, tulip poplar is native only to the Bluff Hills (74a). Shortleaf pine grows on the sandier soils of the northern ridge. |

|

Notes

- The full, original version of this entry is located here: http://www.epa.gov/wed/pages/ecoregions/ar_eco.htm. That description contains additional maps, as well as information on the physiography, geology, soil, potential natural vegetation, and the land use and land cover of the ecoregion.

- PRINCIPAL AUTHORS: Alan J. Woods (Oregon State University), Thomas L. Foti (Arkansas Natural Heritage Commission), Shannen S. Chapman (Dynamac Corporation), James M. Omernik (USEPA, retired), James A. Wise (Arkansas Department of Environmental Quality), Elizabeth O. Murray (Arkansas Multi-Agency Wetland Planning Team), William L. Prior (Arkansas Geological Commission), Joe B. Pagan, Jr. (U.S. Department of Agriculture–Natural Resources Conservation Service), Jeffrey A. Comstock (Indus Corporation), and Michael Radford (Arkansas Soil and Water Conservation Commission).

- COLLABORATORS AND CONTRIBUTORS: Ken Brazil (Arkansas Soil and Water Conservation Commission), Kenneth Colbert (Arkansas Soil and Water Conservation Commission), Philip Crocker (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency), Brian Culpepper (University of Arkansas–Center for Advanced Spatial Technologies), Billy Justus (U.S. Geological Survey), Barbara A. Kleiss (USACE, ERDC–Waterways Experiment Station), Bob Leonard (Arkansas Game and Fish Commission), Thomas R. Loveland (U.S. Geological Survey), Larry Nance (Arkansas Forestry Commission), and Rex Roberg (Arkansas Cooperative Extension Service).

- REVIEWERS: John Giese (Arkansas Department of Pollution Control and Ecology, retired), Robert J. Lillie (Professor, Department of Geosciences, Oregon State University), and Kenneth Smith (Executive Director, Audubon Arkansas).

- CITING THIS POSTER: Woods A.J., Foti, T.L., Chapman, S.S., Omernik, J.M., Wise, J.A., Murray, E.O., Prior, W.L., Pagan, J.B., Jr., Comstock, J.A., and Radford, M., 2004, Ecoregions of Arkansas (color poster with map, descriptive text, summary tables, and photographs): Reston, Virginia, U.S. Geological Survey (map scale 1:1,000,000).

- This project was partially supported by funds from the USEPA Region 6, Biocriteria Program and USEPA–Office of Science and Technology through a contract with Dynamac Corporation. It was also partially supported by funds from the Arkansas Soil and Water Conservation Commission through grants provided by the USEPA Region 6 under the provisions of Section 104(b) (3) of the Clean Water Act (through the wetlands grant program).

Literature Cited

- Bailey, R.G., Avers, P.E., King, T., and McNab, W.H., editors, 1994, Ecoregions and subregions of the United States (map): Washington, D.C., U.S. Department of Agriculture–Forest Service, map scale 1:7,500,000.

- Bryce, S.A., Omernik, J.M., and Larsen, D.P., 1999, Ecoregions – a geographic framework to guide risk characterization and ecosystem management: Environmental Practice, v. 1, no. 3, p. 141-155.

- Chapman, S.S., Griffith, G.E., Omernik, J.M., Comstock, J.A., Beiser, M.C., and Johnson, D., 2004a, Ecoregions of Mississippi (color poster with map, descriptive text, summary tables, and photographs): Reston, Virginia, U.S. Geological Survey, map scale 1:1,000,000.

- Chapman, S.S., Kleiss, B.A., Omernik, J.M., Foti, T.L., and Murray, E.O., 2004b, Ecoregions of the Mississippi Alluvial Plain (color poster with map, descriptive text, summary tables, and photographs): Reston, Virginia, U.S. Geological Survey, map scale 1:1,150,000.

- Chapman, S.S., Omernik, J.M., Griffith, G.E., Schroeder, W.A., Nigh, T.A., and Wilton, T.F., 2002, Ecoregions of Iowa and Missouri (color poster with map, descriptive text, summary tables, and photographs): Reston, Virginia, U.S. Geological Survey, map scale 1:1,800,000.

- Commission for Environmental Cooperation Working Group, 1997, Ecological regions of North America – toward a common perspective: Montreal, Commission for Environmental Cooperation, 71 p.

- Gallant, A.L., Whittier, T.R., Larsen, D.P., Omernik, J.M., and Hughes, R.M., 1989, Regionalization as a tool for managing environmental resources: Corvallis, Oregon, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, EPA/600/3-89/060, 152 p.

- Griffith, G., Omernik, J., and Azevedo, S., 1998, Ecoregions of Tennessee (color poster with map, descriptive text, summary tables, and photographs): Reston, U.S. Geological Survey, scale 1:940,000.

- Küchler, A.W., 1964, Potential natural vegetation of the conterminous United States (map and manual): American Geographic Society, Special Publication 36, map scale 1:3,168,000.

- McMahon, G., Gregonis, S.M., Waltman, S.W., Omernik, J.M., Thorson, T.D., Freeouf, J.A., Rorick, A.H., and Keys, J.E., 2001, Developing a spatial framework of common ecological regions for the conterminous United States: Environmental Management, v. 28, no. 3, p. 293-316.

- Omernik, J.M., 1987, Ecoregions of the conterminous United States (map supplement): Annals of the Association of American Geographers, v. 77, p. 118-125, map scale 1:7,500,000.

- Omernik, J.M., 1995, Ecoregions – a framework for environmental management, in Davis, W.S., and Simon, T.P., editors, Biological assessment and criteria – tools for water resource planning and decision making: Boca Raton, Florida, Lewis Publishers, p. 49-62.

- Omernik, J.M., Chapman, S.S., Lillie, R.A., and Dumke, R.T., 2000, Ecoregions of Wisconsin: Transactions of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts, and Letters, v. 88, p. 77-103.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture–Soil Conservation Service, 1981, Land resource regions and major land resource areas of the United States: Agriculture Handbook 296, 156 p.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2003, Level III ecoregions of the continental United States (revision of Omernik, 1987): Corvallis, Oregon, USEPA–National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory, Western Ecology Division, Map M-1, various scales.

- Wiken, E., 1986, Terrestrial ecozones of Canada: Ottawa, Environment Canada, Ecological Land Classification Series no. 19, 26 p.

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the Environmental Protection Agency. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the Environmental Protection Agency should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |