Eastern Africa and biodiversity

| Topics: |

Contents

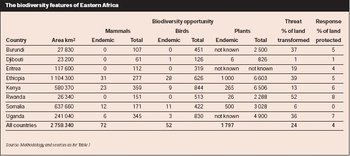

- 1 Overview of resources Nectophrynoidesvivparus is one of the few frogs that give birth to live young. This vulnerable species occurs in the Uluguru and Udzungwa mountains in the southern highlands of Tanzania. (Source: D. Moyer/WCS) Eastern Africa’s biological diversity reflects its position astride the equator and the high variability of landscapes and aquatic ecosystems. These conditions provide suitable habitat for a large variety of living organisms, some with very limited ranges. For instance, the Bonga Forest in Ethiopia contains more than 15 species of highland birds; the Metu-Gore-Tepi forest has more than 16 species of birds of which at least two are endemic, while the Tiro Boter-Becho forests have more than 32 highland biome (Eastern Africa and biodiversity) species of birds. A total of 277 species of mammals are known in Ethiopia, of which 29 are endemic and almost exclusively confined to the central plateaus. Uganda also has a high diversity, with over 1,000 species of birds being recorded, a significant percentage of Africa’s 2,313 bird species; these it owes to its combination of semi-arid savannahs, lowland and montane rain forests, vast wetlands, and an Afroalpine zone which ranges in altitude from 650 to 5,000 meters (m). The diverse habitats of Eritrea, from scorching sub-desert flatlands to mist-enshrouded evergreen montane forests, hold a wide variety of birds, many of which are confined to the Horn of Africa. Burundi has its fair share of diversity as well, with a total of 107 mammal species having been recorded to date. Meanwhile, the Masai Mara of Kenya is world-famous for big game. As elsewhere, many of Africa's animal - and plant - species are threatened with extinction. For instance although Djibouti does not have any endemic mammals, the following threatened terrestrial and marine species occur there: African Wild Dog (Lycaon pictus), Beira Antelope (Dorcatragus megalotis), Dorcas Gazelle (Gazella dorcas), Large-eared Free-tailed bat (Otomops martiensseni), Soemmerring’s gazelle (Gazella soemmerringii) and Dugong (Dugong dugon).

- 2 Challenges faced in realizing opportunities for development

- 3 Strategies to enhace the opportunities for development

- 4 Further reading

Challenges faced in realizing opportunities for development

Maintaining biodiversity is essential for ensuring that the environmental goods-and-services are maintained.

Eastern Africa contains some of the world’s oldest and richest protected areas (Table 1), such as the Tsavo, Queen Elizabeth and Serengeti national parks. The principle which guided establishment of most protected areas was that strict protection was essential for effective conservation of biological resources and therefore the exclusion of humans, livestock and fire was considered necessary. This protectionist approach was based on the USA’s Yellowstone National Park. These protected areas were established in the hope that they would continue to exist in pristine state and effectively conserve the inherent biological diversity, especially the characteristic large mammal aggregations. This idea was enshrined in such notable Multilateral Enviornmental Agreements (MEAs) as the London Convention of 1933 and the ACCNNR of 1968. While the present distribution of protected areas embraces a more modern view of the broader biodiversity concept, it still reflects a preoccupation with the large mammal concentrations. The long-term viability of the ecological systems and processes on which such areas depend remains questionable. The exclusion of humans and most of their activities notwithstanding, species loss has continued. In nearly all cases, park boundaries were established with little regard for the year-round needs of resident fauna. For example, the Nairobi National Park and Masai Mara reserve in Kenya were originally designed to conserve populations of migratory mammals whose movements have since been severely restricted. Land conversion and encroachment of these areas, and virtually all other protected areas, have led to serious ecological isolation with negative effects on species richness, abundance and genetic vigour.

In several areas, such as the Nairobi and Mkomazi parks, large mammal populations have become more compressed, and animal and plant species diversity has decreased. Rapid biodiversity loss in some of Kenya’s protected areas is also closely linked with the explosion of tourism, rapid coastal development, and spread of human settlements since the 1970s. The large mammal populations of Uganda’s Murchison Falls National Park came under heavy pressure during the years of civil strife, leading to huge species declines and directional vegetation change. In Ethiopia’s Awash, Abijata Shalla and Nechisar national parks, encroachment and settlement forced many wildlife species out of the park due to increased competition for forage.

Although biodiversity loss can be attributed to multiple causes, a large part is accounted for by the real and widespread conflict between people and wildlife. Eastern Africa has a high human population. The spread of cultivation and settlement has meant that pastoralists and their livestock have been squeezed into increasingly smaller areas. There is increasing competition between people, and between people and wildlife, for grazing land and water resources. Local people and their livestock are still viewed by the national law and policy as alien to parks, reserves and sanctuaries. The loss of key dispersal areas for wildlife leads to greater pressure within the protected areas, and heightened human-wildlife conflict. Hostilities have built up as consecutive governments ignore the hardship that wildlife causes people. Despite the obvious economic benefits that wildlife brings, many farmers, herdsmen and ranchers living adjacent to parks look upon wild animals with considerable disdain. Wildlife periodically decimates crops, causes injuries or death to people and livestock, and spreads diseases.

Strategies to enhace the opportunities for development

Since the early 1990s, there has been a growing policy change focus on sustainable use and increased local participation. There is a realization that a “fences-and-fines” approach leads to even more conflicts, unacceptable social inequity, and ultimately the destruction of the resources themselves. A “use it or lose it” philosophy has taken root. The various community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) approaches have yielded mixed results. Nearly all countries are providing greater legitimacy for the involvement of people in natural resources management. A slow but steady change in focus is under way, shifting from the biological challenges to confronting the social and economic issues. In Kenya, for instance, a national land policy is being formulated through a consultative and participatory process. This should open up new opportunities for people wishing to invest in conservation and the sustainable use of biological diversity.

Further reading

- Agrawal,A. and Gibson, C.C., 1999. Enchantment and disenchantment: the role of community in natural resource conservation. World Development. 27(4),629-49.

- Baillie, J., and Groombridge, B., 1996. 1996 IUCN Red List of Threatened Animals. IUCN – The World Conservation Union, Gland.

- BirdLife International (undated). Action for Birds and People in Africa. The conservation programme of Birdlife International Africa Partnership 2004-2008. BirdLife International, Cambridge.

- Carswell, M., Pomeroy, D., Reynolds, J and Tushabe, H., 2005. Bird Atlas of Uganda. British Ornithologists’ Union, Oxford.

- EWNHS, 1996. Important Bird Areas of Ethiopia:A first inventory. Ethiopian Wildlife and Natural History Society and BirdLife International, Addis Ababa.

- FAO, 2003. Forestry Outlook Study for Africa African Development Bank, European Commission and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

- Gebre Michael T., Hundessa, T. and Hillma, J.C., 1992. The effects of war on world heritage sites and protected areas in Ethiopia. In World Heritage Twenty Years Later. Papers presented during the workshops held during the IV World Congress on national parks and protected areas, Caracas,Venezuela, February 1992 (ed.Thorsell, J.C.), pp 143-50. IUCN – The World Conservation Union, Gland.

- Gibson, C.C., 1999. Politicians and Poachers – The Political Economy of Wildlife Policy in Africa. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Groombridge, B., and Jenkins, M.D. (eds. 1994). Biodiversity Data Sourcebook.WCMC Biodiversity Series No.1.World Conservation Press, Cambridge.

- Groombridge, B. and Jenkins, M., 2002. World Atlas of Biodiversity: Earth’s Living Resources in the 21st Century. University of California Press, Berkeley.

- Hilman, J.C., 1991. The current situation in Ethiopia’s wildlife conservation areas. Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Organisation, Addis Ababa.

- Jacobs, M.J. and Schloeder, C.A., 2001. Impacts of Conflict on Biodiversity and Protected Areas in Ethiopia. Biodiversity Support Program,Washington, D.C.

- Kaltenborn, B.P., Nyahongo, J.W. and Mayengo, M., 2003. People and wildlife Interactions around Serengeti National Park: Biodiveristy and the Human-wildlife Interface in Serengeti, Tanzania. NINA Project. Report No. 22. Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, Lillehammer.

- McNeely, J.A., Harrison, J., and Dingwall, P. (eds. 1994). Protecting Nature; Regional Reviews of Protected Areas. IUCN – The World Conservation Union, Gland.

- Songorwa,A.N., Bührs,T. and Hughey, K., 2000. Community-based wildlife management in Africa: a critical assessment of the literature. Natural Resources Journal. 40(3), 603-43.

- Swanson, T.M., 1992. The role of wildlife utilisation and other policies for biodiversity conservation. In Economics for the Wilds:Wildlife, Diversity and Development (eds. Swanson,T.M. and Barbier, E.B.), pp 65-102. Island Press, Washington, D.C.

- UNEP, 2006. Africa Environment Outlook 2.

- Western, D., 1997. In the Dust of Kilimanjaro. Shearwater Books/Island Press,Washington, D.C.

- White, F., 1983. Vegetation of Africa – a descriptive memoir to accompany the Unesco/AETFAT/UNSO vegetation map of Africa. Natural Resources Research Report No. 20. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, Paris.

- Yalden, D.W., Largen, M.J. and Kock, D., 1986. Catalogue of the mammals of Ethiopia. 6. Perrissodactyla, Proboscidea, Hyracoidea, Lagomorpha,Tubulidentata, Sirenia and Cetacea. Monit. Zool. ital. N.S. Suppl. 21(4), 31-103.

- Yeager, R. and Miller, N.N., 1986. Wildlife,Wild Death: Land-use and Survival in Eastern Africa. State University of New York Press, Albany.

|

|

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |