Cooperative Climate: Chapter 2

Contents

- 1 The Need for Energy Efficiency Cooperation

- 2 2.1 What Energy Efficiency Can Do for East Asia – and the Planet

- 3 2.2 Domestic Political Context of Energy Conservation – Increasing Political Attention

- 4 2.3 Common Interests in Energy Efficiency: Beyond the Climate Policy Stalemate

- 5 2.4 Why the CDM Cannot Deliver Massive Energy Savings

- 6 2.5 Conclusion

- 7 Notes This is a chapter from Cooperative Climate: Energy Efficiency Action in East Asia (e-book). Previous: Chapter 1: Climate Change, Asian Economy, Energy and Policy (Cooperative Climate: Chapter 2) (Cooperative Climate: Chapter 2) |Table of Contents (Cooperative Climate: Chapter 2)|Next: Part II: Existing Energy Efficiency Cooperation in East Asia

The Need for Energy Efficiency Cooperation

By Taishi Sugiyama, Gørild Heggelund and Takahiro Ueno

This chapter explains why more cooperation is needed on energy efficiency and conservation. Energy efficiency is key to achieving sustainable development in East Asia and offers multiple benefits, including: energy security; economic efficiency; and mitigation of local and global environmental problems, including climate change. There has been increasing political attention paid to energy efficiency and conservation, with many new policies implemented in the region. International cooperation enhances domestic policy, promotes energy efficiency and serves as an institutional vehicle to go beyond the political stalemate of recent international climate policy.

2.1 What Energy Efficiency Can Do for East Asia – and the Planet

The oil supply shock in 1973 was the first political event that forced policy leaders worldwide to become aware of the importance of—and opportunities for—energy efficiency policy. Energy security and competition in international trade served as the major drivers for launching energy efficiency policies in many countries. Serious policies were designed and implemented in developed countries and then more gradually in developing countries. While the modality and seriousness of policies differ across countries, there have been many lessons learned and we can point to many successful energy-reducing policies.

In the late 1990s, climate change emerged as another key driver for improving energy efficiency. In previous decades, energy conservation policy was not stable in many countries. Policies were introduced when oil prices were high, but they were pulled back when prices dropped. However, the climate change issue emerged as another, stable policy driver since the adoption of the Kyoto Protocol (Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (full text)) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in 1997. As the deadline for developed countries to cut greenhouse gas emissions nears (2008–2012), there is greater recognition that improving energy efficiency is a major objective for achieving CO2 emission cuts.

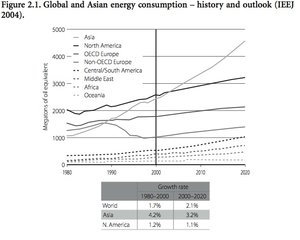

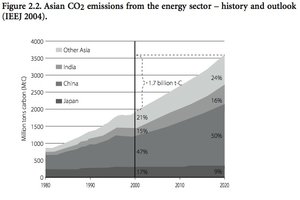

Energy efficiency is particularly important in East Asia where economies and energy demand are growing rapidly. Asia has been the growth center of the world economy and energy consumption in the last two decades, and energy consumption may grow even faster in the coming two decades (Figure 2.1). This energy growth suggests that there will be a significant increase in CO2 emissions, given the region’s high dependence on coal, particularly in China and India (Figure 2.2).

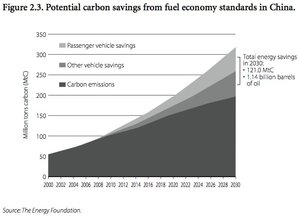

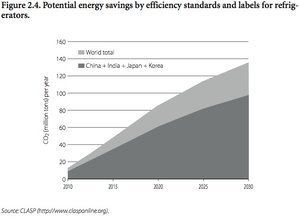

It is known that there is great potential for reducing energy consumption and CO2 emissions through accelerated energy efficiency policies. In China alone, fuel economy standards for automobiles are expected to reduce oil consumption by 1.14 billion barrels while reducing carbon emissions by 121 million tons (or 443 million tons of CO2) in 2030 (Figure 2.3). Standards and labels to promote energy-efficient refrigerators can reduce electricity use by 117 TWh (Tera Watt-Hour) and reduce CO2 emissions by 97.6 million tons by 2030 in four Asian countries: China (Energy profile of China), India (Energy profile of India), Japan and Korea (Energy profile of South Korea) (Figure 2.4). Ninety-five to 110 million tons of CO2 emissions in the iron and steel sector and 330 to 380 million tons of CO2 emissions in the cement sector can be cut by 2030 by using the best available technologies today (Tanaka et al., 2006).

There is potential for intensive policy implementation on energy efficiency to slow the expansion of the primary energy supply. This will reduce the financial burden for the infrastructure development, the geopolitical tension over overseas supply sources, and CO2 emission sources. It’s important to note that energy infrastructure can last as long as several decades. Also noteworthy is that carbon-free supply technologies, including nuclear, renewable, and carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies for fossil fuel facilities are still in limited use globally. Therefore, it is critical to buy time by implementing energy efficiency policies and avoiding the expansion of highly carbon-intensive infrastructure, until the carbon-free technologies are well-developed, affordable and available to East Asian countries in the coming decades.

2.2 Domestic Political Context of Energy Conservation – Increasing Political Attention

East Asian countries have already become aware of the importance of energy efficiency and have begun taking action. In this section, our primary focus is on China.

A. China’s current energy policy and political setting

China’s dependency on coal as its primary energy source (67.7 per cent of total energy consumption, China Statistical Yearbook, 2005) has made energy efficiency an increasingly important component of China’s current energy policy. With 114 billion tons of known coal reserves, China (Energy profile of China) will continue to be dependent upon coal for the foreseeable future, and by 2030, coal is expected to constitute 53 per cent [1] of total energy consumption. China announced in 2001 plans to quadruple its GDP before 2020, while only doubling its energy consumption. This objective provides serious challenges for China as energy consumption increases.

Policy and legal system

Energy conservation has been an important element of the political agenda in China for over two decades, and the focus on energy efficiency has yielded results. From 1980 to 2000, China’s energy only doubled, while its GDP quadrupled (NESP, 2005; Sinton et al., 2005). China’s GDP increased by 9.7 per cent during the period, while the average energy intensity rose by 4.6 per cent. About 1,260 Mtce was saved between 1981 and 2002 while China’s goal of supplying enough energy to sustain economic growth was still met. China’s Ninth Five-Year Plan for Social and Economic Development (1996–2000) suggested for the first time explicit and detailed energy strategy, making energy saving a priority. During that period, China’s Energy Conservation Law entered into force (on January 1, 1998).[2] The 10th Five-Year Plan for Social and Economic Development (2001–2005) placed energy conservation at the top of the energy policy agenda. Improving energy efficiency and spreading energy-saving technologies were two of the Plan’s main energy policy objectives. Diversification of China’s energy mix and development of new sources of energy and [[renewable] energies] were also identified. The 10th Five-Year Plan for Energy Conservation and Comprehensive Resource Utilization, a key document attached to the 10th Five-Year Plan, set specific goals for energy conservation. Another important policy document that illustrates the increasing political attention paid to the energy issue by China’s leadership, including energy efficiency, is the China Medium- and Long-Term Energy Conservation Plan (2004–2020) issued by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). The Plan stresses China’s enormous potential to save energy.

There have been several recent signs that China’s leadership feels the urgency of the current energy situation and the need to slow down energy consumption. During the National People’s Congress (NPC) in March 2006, energy efficiency was emphasized as a key measure of economic growth by Premier Wen Jiabao who proposed a four per cent reduction in energy intensity for 2006 in his report. Energy intensity is energy consumption per unit of gross domestic product (GDP). From 2006, the energy consumption per unit of output for all regions and major industries will be made public on an annual basis. Moreover, the 11th Five-Year Social and Economic Development Program [3] was recently issued and names improved energy efficiency as a major objective; the goal is to reduce the ratio of total energy use to GDP by 20 per cent in 2010 compared to 2005. Also, a high-level task force has been set up to draft a law on energy (with representatives from a number of ministries). In a rare move, the government has called on the public to provide input to the drafting of the new energy law.

In the state media, Chinese leaders have expressed their concern with the current energy situation, illustrating the increased attention being paid to the energy issue.[4]In addition to the domestic pollution problems and energy security issues related to energy consumption, China’s growing GHG emissions deeply trouble China’s leaders and the issue has been addressed in the state media (see China Climate Change Info Net, 2004). A heightened awareness among China’s leaders that energy shortages and pollution problems limit economic growth is another reason for the emerging focus on energy efficiency. Policy measures and initiatives have been carried out to achieve energy efficiency in China. Efforts by the government to increase overall energy efficiency have included: the reduction of coal and petroleum subsidies; investments to improve energy efficiency; and China has “drafted and implemented a series of incentive policies in terms of finance, credit and taxation toward energy conservation projects including interest payment rebates, differential interest rates, revoking of import taxes and reduction of income tax, etc.”. Several priority projects that concern development of technologies and equipment for clean energy programs were targeted under the 10th Five- Year Plan such as the 863 Program, and the National Key Technologies R&D Program. Policy studies have been issued, such as China’s National Comprehensive Energy Strategy and Policy by the Development Research Center of the State Council in 2005. Efforts have been carried out to increase awareness in the industrial sector and projects have been implemented such as the development of Energy Saving Companies (ESCO) and Energy Management Companies (EMC) with GEF grants, and loans from the World Bank and the Chinese government. Also, programs for Voluntary Energy Efficiency Agreements for Iron & Steel plants (in Shandong province, for example) that increase their efficiency efforts have been carried out with foreign assistance. The Efficient Lighting Initiative (ELI) is another initiative that has been adopted by China to increase efficiency (see Chapter 5 (Cooperative Climate: Chapter 2) on the ELI). The ongoing efforts to introduce standards and labeling for electrical appliances have yielded dramatic results in China (see Chapter 4 (Cooperative Climate: Chapter 2) for Collaborative Labeling and Appliance Standards Program (CLASP) efforts in China). The Ministry of Construction introduced a pilot program on energy conservation in buildings, and in 2006 more stringent energy codes for new buildings were introduced aimed at cutting energy consumption by two-thirds. Beijing and Shanghai will be experimental cities and the rest of the country is expected to follow by 2010 (Xu, 2005)

While ongoing efforts have been effective, the potential for energy efficiency in China is still large. Chinese industries are typically less energy efficient than their counterparts in other countries. Energy efficiency potential in the industrial sector is large as energy intensity is still higher on average (about 40–50 per cent) in China than in Western industrialized countries. Moreover, coal consumption is rising after declining in the late 1990s. Energy shortages and growing domestic air pollution problems are major reasons for the recent urgency to increase energy efficiency. China’s reaction to the power shortages (which occurred in 24 out of 31 provinces in 2004) has been to construct new power plants, with 66 GigaWatt (GW) built in 2005 alone, and over 70 GW planned to come online in 2006. The energy savings potential from developing more efficient electrical appliances (TVs, refrigerators and lighting) is large and could save 10 per cent of all residential energy by 2010 (Ogden, 2006). Energy codes for buildings have been introduced, but the effective implementation of these codes has been slow as less than five per cent of constructed urban buildings comply with the design codes of building energy conservation (NDRC, 2005). Some of the areas of potential improvement are energy structure, technology and management. In addition, low managerial capacity, the lack of efficient implementation of existing laws and outdated equipment—combined with increasing energy demand—emphasize the need for focusing on energy efficiency. Lack of funding is another issue. In 2004, China spent 424 billion Yuan on energy supply compared to 23 billion on energy conservation.

Institutions

Recently, the increased focus on energy challenges in China has resulted in the establishment of new energy authorities. On the institutional side, China has varied the centralized governmental energy authorities over the years. The Energy Bureau in the NDRC has had the primary responsibility for China’s energy industry since 2003 when institutional changes took place. The then State Development and Planning Commission (SDPC) was renamed the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). The State Economic and Trade Commission (SETC) that was responsible for energy related matters was abolished, and the NDRC took over many of the responsibilities. The Energy Bureau of the NDRC became responsible for energy supply, while energy consumption and efficiency belong to a division of the environment department (Department of Environment and Resources Conservation). In the same year, the State Electricity Regulatory Commission was also established. After several years of growth, it remains weak, with the key functions of setting electricity rates and approving projects remaining with NDRC’s Pricing Department and Energy Bureau respectively. The State Administration for Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine, is responsible for setting standards of all sorts, including efficiency standards for appliances and lighting equipment.

Further institutional changes include the establishment of the Office of the National Energy Leading Group in 2005, which is an office at the ministerial level led by Ma Kai, the NDRC minister. The office is in charge of overall energy strategy, but its actual functions are unclear. The office serves the National Energy Leading Group, a high-level task force led by Premier Wen Jiabao (and vice premiers Huang Ju and Zeng Peiyan) that meets annually.[5] It is still unclear what the results of these institutional changes will be and whether they will strengthen energy policy-making and coordination. Some believe that the National Energy Leading Group may be a forerunner to the establishment of a new Ministry of Energy, and they advocate for the establishment of such a ministry with a clear mandate and the authority to achieve efficient implementation of energy policy.

Based on the study of developments in China’s energy policy, supplemented by interviews and a workshop in Beijing, it is clear that the political climate for action on energy efficiency is favorable and the political will to cooperate is there.

B. Current energy efficiency policies in East Asia

China is not the only country that has addressed energy efficiency policy seriously. Almost all East Asian countries have adopted and implemented policies aimed at energy efficiency in recent decades. This section discusses the current realities.

Typology of policies

There is a variety of policies for energy efficiency. They differ across sectors and national conditions. A typology of policies includes the following:

- information sharing (on policy design, technologies, etc.);

- setting energy conservation goals;

- setting technology dissemination goals;

- reporting programs;

- training and education;

- setting minimum energy performance standards on energy-efficient technologies including appliances, equipment, lighting products, industrial processes, whole buildings and automobiles;

- labeling programs for technologies;

- “top-runner” or “best available technology” programs;

- voluntary (or negotiated) agreements, especially in the industrial sector;

- energy manager system;

- technology research, development and demonstration;

- support for Energy Saving Companies (ESCOs) or Energy Management Companies (EMCs);

- governmental procurement of efficient technologies;

- financial incentives:

- favorable lending terms for investments;

- special loan funds dedicated to energy efficiency;

- incentives for investments in energy-efficient technologies; and

- rebates for highly efficient products;

- recognition and awards for enterprises, agencies and individuals;

- fines, fees and other punitive measures for non-compliance or as a disincentive;

- support for technological research, development and demonstration; and

- education on energy efficiency for all players.

While many of them are already well-known, it might be helpful to add some explanations and examples. Efficiency standards are either mandatory or voluntary and they aim at transforming the technology market by eliminating products that do not meet efficiency standards. Labeling is a communication method of sharing efficiency information with consumers in order to encourage the production of more efficient equipment. Voluntary agreements are the agreements between the business sector and the government to engage in energy efficiency programs. There is a wide variety of voluntary agreements. One example is endorsement labeling programs such as ENERGY STAR. Another example is negotiated agreements between government and private companies to improve energy efficiency. The energy manager system is a system that mandates companies to designate energy managers in charge of energy efficiency improvement at their factories. Energy managers are required to have expertise and training and must regularly report on energy consumption. Governmental procurement is a governmental activity designed to procure energy-efficient products in order to build demand for cutting-edge, energy-efficient technologies.

Institutions, policies to date

Tables 2.1 through 2.9 summarize the current status of energy efficiency policy and institutions in East Asian countries. In most countries, there are dedicated energy ministries and/or agencies present (Table 2.1). Also, most countries have energy conservation laws and/or long-term plans to guide their individual energy efficiency policies (Table 2.2). While there are energy efficiency standards and labels for refrigerators and air conditioners in most countries, many countries lack standards and labels for washing machines (Table 2.3) and dozens of other energy-consuming products. Half of the countries lack energy efficiency standards (often called codes) for dwellings, although most countries have them for public and commercial buildings (Table 2.4). Countries also differ with respect to having other policies and energy reduction measures such as “reporting, energy manager, and energy saving plan” requirements (Table 2.5); fiscal measures (Table 2.6); economic incentives (Table 2.7); energy audits (Table 2.8); and voluntary agreements (Table 2.9).

The terms that capture attention here are: progress, diversity, convergence and opportunity. First of all, there has already been progress in developing institutions in all countries. This serves as a firm basis for further improving energy efficiency. There is no need to start this process from scratch, and any isolated efforts without taking region-wide progress into account would be futile. Diversity is an obvious concept, even at this superficial level of summary. The types of policies adopted differ across countries. This implies that steady progress within individual sectors of an individual country, in harmony with individual energy efficiency regimes that reflect the priorities and history of that country, is far more important than seeking a “one-size-fits-all” solution that would aim to address all countries and sectors simultaneously. On the other hand, convergence is observed when the set of Policies (Cooperative Climate: Chapter 2) is seen from a wider perspective. This means that no country will adopt a completely different set of policies from the rest of the world to address energy efficiency. Countries have similar sets of policies in general, with many differences in details. This implies two things. First of all, there are policies that have generally proven, or at least are perceived to be proven, to be effective in meeting the goals. Second, there is a wide range of opportunities for international cooperation. Countries are promoting similar policies to meet similar goals. This means that there are many resources to be shared among the involved nations, including intellectual knowledge, practical lessons of successes and failures, personnel resources that embody them, and enthusiasm and shared values toward more energy efficiency.

An immediate caveat to the tables is the shallowness of the summary. In particular, differences in ambitiousness and legal systems are lacking. Ambitiousness of standards and labeling differs across countries. In some countries standards are set at an ambitious level so that only cutting-edge energy efficiency equipment is able to survive in the market. In some other countries, however, the level of standards is low, reflecting the capacity of domestic manufacturers and people’s willingness to pay for up-front costs.[6]

Legal systems also differ across countries. In Japan, if laws and standards are stipulated, compliance with them usually follows without harsh enforcement in many cases. Publicizing the non-compliance is seen by companies as a very heavy penalty. In many other countries, however, laws and standards are seen as meaningless without the presence of strong enforcement and heavy penalties, such as fines or imprisonment. Japan used voluntary agreements and non-mandatory requirements as the major instruments on every front of environmental policy, of which pollution control agreement and top-runner systems for appliance standards are most famous, and have succeeded in controlling the environmental quality to some extent. It is an interesting lesson, but applying it to the rest of world may not be appropriate. This is not to say that one country is better or worse than another, but the differences in their legal systems must be recognized. This, therefore, suggests that fine-tuned, perhaps different, legal approaches in promoting energy efficiency in individual countries are needed.[7]

|

Table 2.1. Institutions in charge of implementing energy efficiency programs. | ||

| National energy efficiency agency (Existence/name) |

| |

| Australia | No | • (2) °(3) |

| China | ° | |

| Hong Kong, China | ° | |

| India | • (BEE) | • |

| Indonesia | ° | |

| Japan | •* | • (9) |

| Korea | • (KEMCO) | |

| Malaysia | • (PTM) | |

| Philippines | ° | ° (2) |

| Taiwan, China | ° | |

| Thailand | • (DEDE) | • (5) |

| Vietnam | • (VECP) | • (6) |

| • National agency; ° Ministry department rather than separate agency. *Agency covering energy efficiency and supply. | ||

| Source: WEC 2004 | ||

|

Table 2.2. Existence of national energy efficiency programs. | |

| Australia | Safeguarding the future 1998-2004: Constrain emissions growth to eight per cent above 1990 levels |

| China | National Energy Conservation Project 2001-2005 Medium- to Long-term Energy Conservation Plan |

| Hong Kong, China | Nothing |

| India | Energy Conservation Law |

| Indonesia | Energy Conservation Program 2003-2010: Reduction of the energy intensity of one per cent per year |

| Japan | Energy Conservation Law |

| Korea | Second Energy Rationalization Energy Plan 1999-2003 (10 per cent savings in 2003) |

| Malaysia | Malaysian Industrial Energy Efficiency Improvement Program 2000-2004 (10 per cent saving) |

| Philippines | Energy Conservation and Efficiency Program 2000-2001; Promotion of Energy Efficient Use Law (2000) |

| Taiwan, China | Energy Efficiency and Conservation Program: 28 per cent reduction in the energy intensity of the GDP by 2020 (16 per cent in 2010) |

| Thailand | ? |

| Vietnam | Vietnam Energy Conservation Program 2003-2005 |

| Source: WEC 2004 | |

|

| |||

| Refrigerators | Washing machines | Air conditioners | |

| Australia | M (1999, 2005) | L | M (2001/04/07) |

| China | L (2004), M (1989/2000) | M (1989) | M (1989/2001) |

| Hong Kong, China | No | No | No |

| India | P (2005) | No | No |

| Indonesia | p (2005) | No | No |

| Japan | M (1999) | M (1999) | |

| Korea | L, M (2001) | L, M (2001) | L, M (1993) |

| Malaysia | No | No | No |

| Philippines | M (2000) | M (1993/2002) | |

| Taiwan, China | M (2000) | M (2002) | |

| Thailand | L, M (2004) | L, M (2004) | |

| Vietnam | P | P | P |

| L: Mandatory labels; M: Mandatory efficiency standards; V:Voluntary standards; P: Under preparation | |||

| Source: WEC 2004 | |||

|

Table 2.4. Thermal energy efficiency standards for new buildings. | ||||||

| Year | Dwelling Status |

Savings | Year | Building Status |

Savings | |

| Australia | 2003 | P | 2003 | P | ||

| China | 1995 | M | 1995 | M | ||

| Hong Kong, China | No | 1995 | M | |||

| India | No | 2001 | P | |||

| Indonesia | No | 2000 | V | |||

| Japan | 1999 | M | 1999 | M | ||

| Korea | 1994 | M | 2001 | M | 10% | |

| Malaysia | No | 2001 | P,V | |||

| Philippines | No | 1994 | M | |||

| Taiwan, China | 1995-2002 | M | 20% | 1995-2002 | M | 5-10% |

| Vietnam | P | P | ||||

| M: Mandatory; P: Planned; V: Voluntary. | ||||||

| Savings: consumption reduction compared to buildings built before the enforcement of the standards. | ||||||

| Source: WEC 2004 | ||||||

|

Table 2.5. Other Regulations. | ||||

| Mandatory consumption reporting |

Mandatory energy managers |

Mandatory energy saving plan |

Mandatory maintenance | |

| Australia | ||||

| China | ||||

| Hong Kong, China | ||||

| India | ||||

| Indonesia | S | I | Yes* | |

| Japan** | I, S | I, S | I, S | |

| Korea | I, S | I, S, U | ||

| Malaysia | ||||

| Philippines | I, T, S | I | I, T, H, S | |

| Taiwan, China | I, T, H, S | I, T, H, S | I, T, H, S | |

| Thailand | Yes | |||

| Vietnam | ||||

| I: Industry; S: Services; H: Households; T: Transport; Empty cell: No Measure | ||||

| *Objective of 320 MW; by October 2002, power saving of 7 MW; target of 150 MW for 2003 | ||||

| **Factories which consume large amounts of fuel or electricity (more than 3,000 kL of fuel per year in crude oil equivalent or more than 12 GWh of electric power per year) are subject to the mandatory requirement. | ||||

| Source: WEC 2004 | ||||

|

Table 2.6. Fiscal measures. | |||

| Tax credit or tax reduction | Accelerate depreciation | Tax reduction | |

| Australia | |||

| China | |||

| Hong Kong, China | |||

| India | |||

| Indonesia | |||

| Japan | I, S, H | I | |

| Korea | I, S, H, T | I, S, H | |

| Malaysia | I | I | I, S |

| Philippines | |||

| Taiwan, China | I, S | ||

| Thailand | I | ||

| Vietnam | |||

| I: Industry; S: Services; H: Households; T:Transport; Empty cell: No measure. | |||

| Source: WEC 2004 | |||

|

Table 2.7. Economic incentives, by sector. | ||||

| Investment subsidies | Soft loans | Energy efficiency funds (type/budget) |

ESCO (number/ turnover) | |

| Australia | Various funds* | (60-70) | ||

| China | ||||

| Hong Kong, China | ||||

| India | ||||

| Indonesia | ||||

| Japan | I, S, H | (144) (127 M$) | ||

| Korea | I, S, H, T | (163) (108 M$) | ||

| Malaysia | I | (2.1 M$/yr) | (4) (2.1 M$) | |

| Philippines | I | (6) | ||

| Taiwan, China | I, S, H | (9) | ||

| Thailand | I, S, H | H | ENCON fund | (8) |

| Vietnam | (3 M$/yr) | (4) (2 M$) | ||

| I: Industry; S: Services; H: Households; T:Transport; Empty cell: No measure. | ||||

| *In Australia there are six programs with a total public budget of 25.6 MS/year (US$14 M) | ||||

| Source: WEC 2004 | ||||

|

Table 2.8. Audits | |||

| Dwellings | Buildings | Industry | |

| Australia | S | S (Victoria EPA only) | |

| China | |||

| Hong Kong, China | S (154) | ||

| India | |||

| Indonesia | F, S | F, S | |

| Japan | F (177) | F (200) | |

| Korea | F, S (419) | F, S (1750) | |

| Malaysia | F | F | |

| Philippines | (525) (1979- ) | Yes | |

| Taiwan, China | F, M | F, M | |

| Thailand | M, S (<30%) | S (<30%) | |

| Vietnam | S | ||

| M: Mandatory; F: Free for the consumer (i.e., 100 per cent subsidized); S: Partly subsidized. | |||

| Source: WEC 2004 | |||

|

Table 2.9. Voluntary agreements to reduce energy consumption and/or CO2 emissions. | |

| Australia | • (Variety of programs with voluntary commitments) |

| China | • (two steel companies) |

| Hong Kong, China | No |

| India | No |

| Indonesia | No |

| Japan | • (1) (industry federation) |

| Korea | • (industry and building) |

| Malaysia | • (14) (four with industry associations and 10 with industrial companies) |

| Philippines | • |

| Taiwan, China | • (5) (with industry associations)* |

| Thailand | |

| Vietnam | • (1) (textile industry) |

| *Iron and steel, chemicals, cement, pulp and paper, and man-made fibers; period 1997–2002; target of 1.9 MGloe savings (about 1.7 Mtoe). | |

| Source: WEC 2004 | |

C. Why domestic policies are the key to promoting energy efficiency

Most energy efficiency improvement investments are economically beneficial since the reduced energy costs usually overcompensate for the upfront investment. This is why many people assume that energy efficiency improvement activities simply happen without government support. In reality, however, there are many barriers for energy efficiency improvement (IPCC, 2001, Chapter 5). These include, among others, unstable, distorted or incomplete prices; a lack of information; lifestyle and behavioral influences; and consumption patterns.

For example, imagine you are buying a refrigerator and there are two options: one with a high price and high energy efficiency; the other with a low price and low energy efficiency. If your electricity is heavily subsidized and does not reflect real energy costs, then you will not buy the one with high efficiency. This is the barrier to energy efficiency called distorted or incomplete prices. If there is no information available to show the difference in energy efficiency, you will not choose the one with high efficiency. This is the barrier called lack of information. You may simply not care how much energy is used and will base your choice on color, design, performance or, perhaps, the marketing campaign. This barrier is one of lifestyle and behavior. For the manufacturers of refrigerators, a stable macroeconomic condition is necessary to invest in a production line for more sophisticated refrigerators with high energy efficiency.

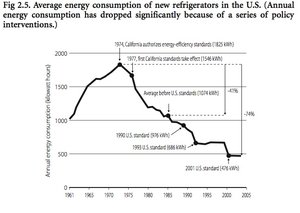

Often, people do not care how much energy is consumed by each appliance. Even if they do care, a lack of information could prevent them from choosing the right one. The same goes for firms. As a result, there are many energy efficiency improvement opportunities ignored by all countries. Often, the payback periods for energy efficiency investment are as short as two years. This means that if you buy a more energy-efficient appliance, then your energy consumption costs would be reduced, and you would recover the extra upfront costs in two years and enjoy the lowered energy costs after that. This is where government can play a role. Governments can provide reliable information as to how much energy is consumed by each appliance. Governments can also set efficiency standards that appliance manufacturers have to meet. There have been many success stories of governmental policies improving energy efficiency (See. Fig. 2.5). It is important to note that energy efficiency improvements will not happen without strong policies to support them.

2.3 Common Interests in Energy Efficiency: Beyond the Climate Policy Stalemate

As we discussed in Chapter 1 (Cooperative Climate: Chapter 2), focusing on cooperative issues could overcome the stalemate that is seen in climate change negotiations under UNFCCC. Here we briefly describe how energy efficiency cooperation serves many policy goals of Japan and other East Asian countries. In Japan, there are six national interests in promoting energy efficiency policies and emission reduction measures in East Asia:

- Energy security. Less energy consumption in developing countries eases competition for sources of supply.

- Regional security. Territorial disputes are often related to mineral resources. Energy conservation would moderate the potential for such disputes. To cooperate on a commonly-beneficial agenda would contribute to mutual trust.

- Market development for highly efficient equipment. Japanese manufacturers will benefit given their high technological capacity to produce highly efficient equipment.

- Incentives for more ambitious efficiency policies in Japan. With the expectation that Asian countries will follow suit in the future, ambitious efficiency policies would be welcomed by policy-makers and manufacturers.

- Climate change mitigation. Japan is committed to climate change mitigation; hence, cost-effective and politically feasible options to cut emissions in developing countries are desirable.

- Trans-boundary air pollution mitigation, such as acid rain.

For developing countries, there are at least six national interests:

- Economic efficiency. Energy efficiency improvement is a key element of productivity and contributes to the economic efficiency of the economy as a whole.

- Development of the market for globally-competitive equipment. China and Southeast Asian countries have used the international system as a vehicle to train and modernize their industries. A notable example is their willingness to participate in the WTO, despite the challenges to some domestic economic sectors.

- Energy security. China (Energy profile of China), Korea and some Southeast Asian countries are highly dependent on imported oil.

- Regional security.

- Pollution prevention.

- Climate change mitigation.

Some of these national interests have been present for decades, but others are new, and the importance of energy efficiency policy is constantly increasing, given burgeoning economic development, energy consumption growth, mounting environmental concerns and territorial tensions in the region. The time seems ripe for further enhancing regional cooperation on energy efficiency that fits within the national interests of all parties.

Although the above argument seems applicable in general, there would be more specific interests and disinterests with a closer look at individual stakeholders; a serious consideration of aligned interests is a prerequisite for politically feasible policy-making. A policy research question throughout this book is how we can save energy while addressing these specific requirements through wise design and implementation of policy.

2.4 Why the CDM Cannot Deliver Massive Energy Savings

The Clean Development Mechanism of the Kyoto Protocol (Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (full text)) has been deemed by the climate policy circle as a key vehicle promoting energy efficiency in developing countries since 1997. While many efforts are still ongoing, and it is too early to judge the program’s success in a comprehensive way, the initial historical record was less than expected and it is not likely that the CDM will bring about major energy efficiency improvements in developing countries. As a consequence, energy efficiency in developing countries is largely missing from the Kyoto Protocol framework and discouraged in practice under CDM.

A. Brief history of the CDM

The CDM has two origins: one is Joint Implementation, as stipulated in the UNFCCC; the other is the Clean Development Fund proposal by Brazil during negotiations in Kyoto in 1997. The intent of the latter was to penalize countries that failed to meet binding targets and to use the revenue obtained from these penalties to assist developing countries. Combining the two origins, Parties created the concept of the CDM and agreed on Article 12 of the Kyoto Protocol. At COP-7, the CDM rulebook (Marrakech Accords) was agreed on and adopted. It specifies organizational bodies such as the EB and DOE and their operational rules.

The Marrakech Accords specify that the CDM Executive Board (EB) supervise the CDM. The EB established the Methodology Panel (Meth Panel). The Methodology Panel, with its technical capability, drafted a recommendation regarding methodologies of baseline and monitoring for the EB’s consideration. The EB began the process of approving new baseline and monitoring methodologies in 2003. They have had 18 meetings since then, and, as of March 2005, have approved 23 methodologies. Also, two consolidated methodologies were approved for landfill methane recovery and renewable power generation connected to an existing power grid.

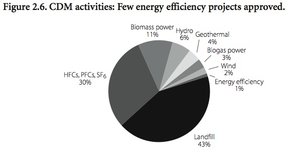

Regarding the types of submitted CDM projects and methodologies, of 89 methodologies submitted by March 2005, 28 address energy efficiency; 24 renewable electricity generation; and 23 fugitive methane emissions. Only four address industrial gases. However, of the 23 approved methodologies, only three address energy efficiency while two address industrial gases; five renewable energy; and nine fugitive methane emissions. Of 74 projects available for public comments in the validation process, 46 concern renewable electricity generation; 24 fugitive methane emissions; and only two energy efficiency. As a result, the major share of the estimated CERs to date comes from landfill methane recovery, HFC deconstruction and N2O deconstruction as shown in Figure 2.6.

Energy efficiency improvement has largely been absent from CDM activities so far. One of the reasons is that it is less straightforward in demonstrating additionality [8] than other types of projects, such as methane recovery and [[renewable] energy] projects. Take the example of energy efficiency improvement investment with a payback period of five years at an office building. This payback time frame is surely longer than common practice in many countries where typical payback periods are one to three years.However, this investment incurs net benefits from the sixth year on; hence people may wonder if the investment would occur regardless of CDM credits. Scientifically, there are methodologies with which you can argue that this project is “additional to what would otherwise occur” by establishing a control group, for example. However, it does not necessarily mean that you can easily convince everyone concerned of the environmental integrity of the CDM.

There are intensive activities going on to develop additionality tests, and baseline and monitoring methodologies that would appropriately reward energy efficiency improvement projects with emission reduction credits of CDM (called Certified Emission Reduction units, or CERs), including the Japanese government initiative titled “Future CDM” (METI/MRI/CRIEPI, 2006). On the international negotiation front, there has been a debate about whether a “Policy CDM” can be credited under the Kyoto Protocol. In other words, if a developing country develops and implements a policy that results in emission reductions, does it deserve CERs? At the COP-11/MOP-1 in Montreal in 2005, countries decided that 1) such a policy would not be credited as CDM, but that 2) activities under such a program can be bundled as a CDM project and can be credited.[9] While it remains to be seen how they are interpreted by the Executive Board and whether they result in projects and emission cuts, it is unlikely that the majority of proven, popular and powerful policy tools reviewed in Section 2.2 (Cooperative Climate: Chapter 2), including emission standards, are to be credited under the CDM. This means there will not be massive energy savings from the CDM.

B. Can the CDM deliver energy efficiency?

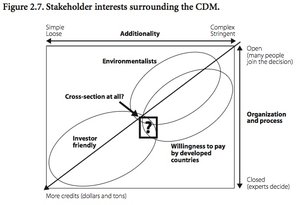

In order to see if the CDM can deliver energy efficiency, let us analyze various expectations and realities surrounding CDM using Figure 2.7. There are two key axes:

- Additionality. Additionality is difficult to define and the effort to do so easily becomes a futile and eternal debate. The situation has become more complex since two different interests are related to the CDM. Environmentalists want strict and complex additionality judgments. The business sector wants simple and quick ones. Finding a satisfactory solution to satisfy both parties is not easy.

- Decision-making institutions and process. If the CDM were a domestic law, then it is the role of the government to judge on additionality and implement it by specifying detailed rules, including administrative order or standards. There are many environmental policies implemented in such a way, even the key concepts and stakeholder arrangements are very complex (e.g., the precautionary principle is a very difficult concept, but countries do manage it in domestic environmental policy). Such an administrative discretion is essential to implement law in practice. But the CDM is different. Large UN organizations, including the UNFCCC secretariat, the Executive Board, Expert Panels, and Conferences and Meetings of the Parties are in charge of its implementation. The process is open to the public to secure political support from environmentalists and developing countries. Being transparent is a very beneficial characteristic for the UN organizations in charge of environmental issues. However, this also means there are a series of hearings and rulings before developing CDM methodologies and CDM projects, and the outcome is highly uncertain. This can impede the effective functioning of business. Stable institutions and legal systems are important for encouraging business investments for the CDM.

In a nutshell, there is a big question as to whether the UN is the appropriate body to print and control the flow of virtual money—in the form of emission credits—in a business-friendly manner. What a UN organization could surely do is create and implement some rules to influence existing market activities such as production activities and commodity flows of timber, for example. Creating a new commodity or printing money and distributing it to the world is a major challenge, and very difficult to achieve for a UN organization. Of course, there are some improvements that could alleviate the concerns raised above. For example, setting some rules that are simple yet transparent and environmentally-sound might be possible. Or, institutional development of a promoting body for the CDM with more permanent specialists may help in such rule-setting. Such efforts could be considered.

There are, however, more fundamental limits to CDM. First is the continuation of a Kyoto (Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (full text))-style binding cap regime itself. It is possible that most countries decide not to take on binding caps for a post-2012 climate regime. If the number of countries taking on binding caps is small, it would be difficult for them to have ambitious targets and, thus, the credit demand created for the CDM would be small.Yet, it is possible to imagine a regime in which a national binding cap is abandoned but incentive for the CDM is created as a government procurement system for certain amounts of CERs in the absence of national cap.

Still, there is a more fundamental limit. That is the willingness-to-pay by developed countries. Imagine that the CDM is the major vehicle for energy efficiency improvement in China. Chinese emissions are four billion tons of CO2 annually. If 10 per cent of them are cut through the CDM and the price of credits are US$10 per ton, then US$4 billion per annum will flow to China. Agreeing upon such an institutional framework, which implies massive financial flows to many developing countries, is impossible in current international politics, in which Japanese ODA is declining and the U.S. is not spending a dollar on ODA to China.

One may argue that once the CDM is regarded as a “market mechanism” and becomes less political, an arrangement implying large financial flows would be possible. One can point to many other decisions affecting larger amounts of financial flows to developing countries—for example, rules regarding foreign direct investment, which dwarfs financial flow generated by the CDM. However, such an argument is weak since the negotiations on the CDM and binding caps are extremely political and there is no sign of change in the near future. Since the CDM is considered very political, it looks like another form of ODA to most policy-makers. If it is indeed another form of ODA, then the CDM is not likely to flourish. It seems extremely difficult and unlikely that countries will agree on binding targets that imply new financial transfers worth billions of dollars.

The key concept of the CDM is that “additional costs” associated with greenhouse gas emissions reduction projects would be paid by developed countries. However, if the CDM is going to cover massive greenhouse gas emissions cuts in developing countries, this very concept exceeds the limit of willingness-today. Then, what is the likely development of the CDM in the future? Our expectation is that the CDM will play only a marginal role in cutting greenhouse gas emissions. Surely it played an important role in addressing methane gas emissions and HFC emissions that would not have been cut otherwise. Furthermore, it may play some role in energy efficiency improvement in some sectors. However, the role of the CDM will remain only marginal, compared to the huge potential energy savings in China and many other countries. The large share of energy efficiency improvement will come from each individual country’s policies. Addressing national policies and promoting further international cooperation will deliver more energy savings than promoting the CDM.

2.5 Conclusion

Energy efficiency and conservation are promising ways to promote economic development and energy security, while simultaneously addressing the environmental impacts of energy use—from local air (Air pollution emissions) and water pollution to global climate change. Despite the need for increased energy efficiency in East Asia, international climate negotiations under the UNFCCC have thus far yielded relatively few efforts on energy efficiency. The Clean Development Mechanism is intended to encourage non-Annex I (developing) countries to participate in greenhouse gas reduction activities, which could include energy efficiency and conservation. In practice, however, current rules concerning baselines and additionality for CDM projects favor methane recovery—not energy efficiency. Precisely because energy efficiency projects can be economically favorable, they have had difficulty gaining approval as CDM projects. Furthermore, other obstacles, including political interests, will likely limit the role of the CDM.

Nevertheless, East Asian countries have been promoting energy efficiency policies within their own borders, as well as engaging in international energy efficiency cooperation. As highlighted in this chapter, most East Asian countries have established government agencies or departments with a mandate to pursue energy efficiency, and have enacted a variety of policies aimed at promoting energy efficiency and conservation. These national energy efficiency efforts were undertaken for multiple reasons, including economic development, energy security and environmental protection. With these common interests, East Asian countries favor international cooperation on energy efficiency. In 2005 and early 2006, dialogue and new initiatives on energy efficiency have greatly increased in the region, creating a political window of opportunity for even further cooperation.

Notes This is a chapter from Cooperative Climate: Energy Efficiency Action in East Asia (e-book). Previous: Chapter 1: Climate Change, Asian Economy, Energy and Policy (Cooperative Climate: Chapter 2) (Cooperative Climate: Chapter 2) |Table of Contents (Cooperative Climate: Chapter 2)|Next: Part II: Existing Energy Efficiency Cooperation in East Asia

Citation

Development, I., Heggelund, G., Sugiyama, T., & Ueno, T. (2012). Cooperative Climate: Chapter 2. Retrieved from http://editors.eol.org/eoearth/wiki/Cooperative_Climate:_Chapter_2- ↑ Under the Reference Scenario of the IEA (2004), by 2030 China and India will account for 48 percent of global coal demand.

- ↑ Other energy-related laws are the Electric Power Law (1996); the Coal Industry Law (1996); the Cleaner Production Promotion Law (2002); and the Renewable Energy Law (2005) that went into effect in January 2006. In addition, there are numerous regulations to direct and standardize energy conservation work (see PRC 2004 chapter four for a list of laws, policies and regulations).

- ↑ The Five-Year Plan (jihua) is now called the Five-Year Program (guihua), implying that the targets should be considered more as guidance than as mandatory goals.

- ↑ One example is General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Hu Jintao’s speech about the energy situation in China on June 28, 2005, (Xin Langwang), where energy efficiency was highlighted as one of the areas requiring focus.

- ↑ Other members of the Leading Group include NDRC Minister Ma Kai, Foreign Minister Li Zhaoxing, Finance Minister Jin Renqing and Commerce Minister Bo Xilai.

- ↑ While energy efficiency programs save costs for consumers in most cases, people often make the decision to purchase equipment based on up-front costs only.

- ↑ For a comprehensive discussion of differences in the national legal systems and their impact on environmental and other political goals, see Kagan and Axelrad (2000), for example.

- ↑ Under the CDM, project participants are mandated to demonstrate the “additionality,” i.e., that the project is additional to what would otherwise occur (baseline). The difference between the baseline emissions and project emissions are credited as Certified Emission Reduction units.

- ↑ The exact wording is as follows. “[COP/MOP-1] Decides that a local/regional/national policy or standard cannot be considered as a Clean Development Mechanism project activity, but that project activities under a program of activities can be registered as a single Clean Development Mechanism project activity provided that approved baseline and monitoring methodologies are used that, inter alia, define the appropriate boundary, avoid double-counting and account for leakage, ensuring that the emission reductions are real, measurable and verifiable, and additional to any that would occur in the absence of the project activity.”