Coastal landform processes

| Topics: |

Geology (main)

|

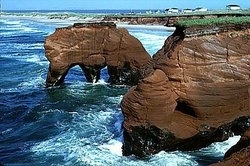

A number of mechanical and chemical effects produce erosion of rocky shorelines by waves. Depending on the geology of the coastline, nature of wave attack, and long-term changes in sea-level as well as tidal ranges, erosional landforms such as wave-cut notches, sea cliffs (Figure 1) and even unusual landforms such as caves, sea arches (Figure 2), and sea stacks can form.

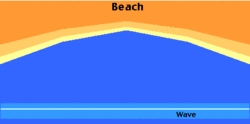

Transportation by waves and currents is necessary in order to move rock particles eroded from one part of a coastline to a place of deposition elsewhere. One of the most important transport mechanisms results from wave refraction. Since waves rarely break onto a shore at right angles, the upward movement of water onto the beach (swash) occurs at an oblique angle. However, the return of water (backwash) is at right angles to the beach, resulting in the net movement of beach material laterally. This movement is known as beach drift (Figure 3). The endless cycle of swash and backwash and resulting beach drift can be observed on all beaches.

When incoming waves strike a shoreline, beach drift can cause the movement of sediment along the shoreline. Beach drift begins when the waves reach the shore at an angle (not parallel) causing the swash and entrained sediment to travel obliquely up the beach (dark blue arows in Figure 3). The returning backwash moves back to the ocean with a direction that is defined by the slope of the beach (light blue arows in Figure 3). The differences in the direction of the swash and backwash cause a net longshore movement of sediment. In Figure 3, this movement is to the center of the beach.

Frequently, backwash and rip currents cannot remove water from the shore zone as fast as it is piled up there by waves. As a result, there is a buildup of water that results in the lateral movement of water and sediment just offshore in a direction with the waves. The currents produced by the laterial movement of water are known as longshore currents. The movement of sediment is known as longshore drift, which is distinct from the beach drift described earlier which operates on land at the beach. The combined movement of sediment via longshore drift and beach drift is known as littoral drift.

Tidal currents along coasts can also be effective in moving eroded material. While incoming and outgoing tides produce currents in opposite directions on a daily basis, the current in one direction is usually stronger than in the other resulting in a net one-way transport of sediment. Longshore drift, longshore currents, and tidal currents in combination determine the net direction of sediment transport and areas of deposition.

Many kinds of depositional landforms are possible along coasts depending on the configuration of the original coastline, direction of sediment transport, nature of the waves, and shape and steepness of the offshore underwater slope. Some common depositional forms are spits, bayhead beaches, barrier beaches or bay-mouth bars, tombolos (Figure 4), and cuspate forelands.

Further Reading