Coastal lagoon (Agricultural & Resource Economics)

Contents

Coastal lagoon

Introduction

According to Kjerfve coastal lagoons are shallow water bodies separated from the ocean by a barrier, connected at least intermittently to the ocean by one or more restricted inlets, and usually oriented shore-parallel. Lagoons are widespread all around the world ocean coasts (Coastal lagoon) . They represent nearly 13% of the shoreline. Their size is quite variable, ranging from less than 1 up to 10,000 km2 (Lagoa dos Patos, Brazil).

Dynamic and productive ecosystems

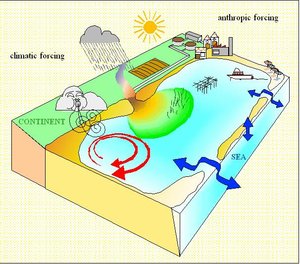

Due to their interface location, between land and sea, and low depth, they are strongly submitted to natural constraints. Consequently, most of these coastal ecosystems are very dynamic and productive. Direct (wind) and indirect (rain through river flows) climatic and marine (tide) influences cause large differences and quick changes in the physical and chemical characteristics of lagoons. Mean water residence time was estimated to be less than one week up to 4 years depending on the lagoon location (tidal, micro tidal areas) and their exchange area with the sea. Horizontal and vertical stratification of water masses is generally strongly dependent of the wind regimes whose frequency and intensity are dependent of regional climate. Hydrological characteristics (e.g. salinity, nutrients) are related to the above-mentioned physical forcing, but also depend on river flows which in turn depend on rain frequency and intensity.

Thus, considering their physico-chemical characteristics, lagoons are diverse at a global scale, but some may also be considered as highly variable environments implying natural stresses on macro- and microorganism populations.

This diversity of environmental conditions implies large differences in the biological production of lagoons (e.g., net primary production values range from 10 to 7000 g carbon m-2 yr-1 over 70 lagoons for which these values have been published,). Some coastal lagoons are thus among the most productive aquatic ecosystems. The primary productivity is mainly supported both by phytoplankton (pico- and nanoplanktonic cells) and macrophytes, their proportion being dependent (and indicative) of the trophic status of lagoons. Recent investigations have shown that macrophyte communities can be highly diverse but also may include a large proportion of exotic species.

Sustained by large primary production, fishery yields can be very high. However, it seems that the higher apparent productivity (i.e., the ratio between fishery captures and primary production) can be reached when large-scale shellfish breeding occurs. The reason is that filter-feeders are able to use phytoplankton production in a more efficient way than fishes.

Human-affected ecosystems

Lagoons in which large primary production occurr may suffer dystrophic crises due to the accumulation of excessive concentrations of organic matter (e.g., from deposited dead macroalgae) and the subsequent increase in bacterial heterotrophic activities leading to a dramatic consumption of dissolved oxygen. The oxygen depletion (sometimes anoxia) allows sulfate reduction to take place. Consequently, hydrogen sulfide accumulates, provoking a large increase in the mortality of macrofaunal species including farmed shellfish. Such dramatic events increase both in frequency and extension as a consequence of eutrophication, which is mainly related to the increase in population density and activities in the lagoon watershed.

These anthropic pressures can also lead to an increase in chemical and microbiological pollution of lagoons. Other environmental crises such as toxic algae blooms and introduction of alien species are increasingly reported, at least in sites where regular surveys are performed. They are linked both to changing environmental conditions and the human use of lagoons (e.g., shellfish transfer, ballast water).

These pressures can lead to ecological disturbances and limit or suppress economic and ecological services that support these ecosystems. From estimates of world surface occupied by lagoons (320,000 km2) and recently published economic values of the world’s wetlands (US$165 ha-1 yr-1), the value of the world coastal lagoons can be estimated at US$5.3 × 109 yr-1 — nearly 10% of the upper total wetlands value estimate.

When adding the potential sea level rise, storm frequency increase, and river flood changes that may occur in the future, coastal lagoons are among the most threatened aquatic ecosystems under global change pressure. Their health status is an indicator of human impact on our living world, and our ability to preserve these ecosystems may also be a good indicator of our ability to promote sustainable development of [[coastal] areas].

Further Reading

- Kjerfve, B., 1994. Coastal Lagoon Processes. Elsevier Science B.V., Amsterdam, xx + 577 p.

- Knoppers, B., 1994. Aquatic primary production in coastal lagoons. In: Coastal Lagoon Processes, Kjerfve, B. (ed.): 243-286. Elsevier Science B.V., Amsterdam, xx + 577 p.

- Schuyt, K. and Brander, L., 2004. The economic values of the world’s wetlands. Swiss Agency for the Environment, Forests and Landscape (SAEFL) Gland/Amsterdam, 29p.