Bradley, Guy (Environmental Law & Policy)

Bradley, Guy

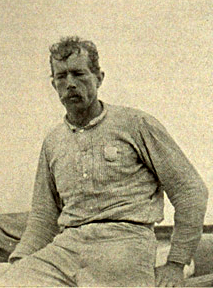

Guy Bradley (1870-1905), the first wildlife law enforcement agent killed while performing his duties to protect the nation's wildlife.

As early as the 1840s, John James Audubon had explored and documented the unrivaled beauty of the Florida Everglades. He marveled at the spears of sawgrass and mangle of mangrove thickets sprouting from a seemingly endless expanse of brackish water which provided a fertile sanctuary to the varied community of fish, reptiles, mammals and birds. This natural beauty lay undisturbed by white settlers until deserters of the Civil War were drawn there to hide. Soon after other, pioneers found their way into the region. With these wilderness settlers came the hunters' tools that spelled devastation for the Everglades' wildlife. First and foremost were the plume hunters anxious to sell their high-quality feathers to the nearest dealer who would then ship them north to millinery traders in fashionable cities along the east coast. Guy Bradley was one of those hunters.

Even before the turn of the century there were land development schemes throughout south Florida. Bradley's father had moved his family to the isolated community of Flamingo near Cape Sable as an agent for a land contractor. His son married there and made his living as a land surveyor, hunting plume birds in the Everglades and selling them to dealers for sport and to supplement his income.

In 1902, just after passage of the Lacey Act, Kirk Munroe, a member of the Florida Audubon Society visited the southern coast of Florida down through the Keys and witnessed first-hand the on-going destruction of plume birds. He urged the appointment of a game warden in an attempt to put an end to the carnage. In Guy Bradley, Munroe believed he had found just the man he needed. Bradley, he wrote, was "a thorough woodsman, a plume hunter by occupation before the passage of the present law, since which time, as I have ample testimony, he has not killed a bird." Munroe believed there to be "no better man for game warden in the whole state of Florida than Guy." Bradley accepted the job of warden representing the American Ornithologists' Union at a monthly salary of $35.

Bradley's job was clearly a dangerous one. His first directive on accepting the position was to report the names of local plume hunters as well as the firms with which they did business in New York. Bradley was intimately acquainted with many of these hunters having once done business with them himself, but his response to the Union's request included a statement saying he was no longer a hunter but a protector. He now believed that killing plume birds is "a cruel and hard calling...I will certainly do all that I can to find out who are the New York buyers." Bradley was true to his word. He even went so far as to write to the dealers asking for price lists in order to use their replies against them.

Florida's Audubon Society was concerned for Bradley's safety from the very beginning. The area under Bradley's supervision was rife with hunters who had no qualms about violating the law. News that a warden was now prepared to protect Florida's birds put Bradley in a precarious position. Still, he was dedicated to his job. On one inspection, Bradley escorted two [[from Washington deep into the Everglades to view the Cuthbert Rookery. His guests were impressed with Bradley's endurance and resourcefulness and rewarded with the sight of three thousand pair of various birds nesting there at the time.

But as Bradley kept watch over this rookery and other local [../153222/index.html habitats]], the plume hunters kept watch over him. On another trip the following year, Bradley and his guest found the bodies of more than four hundred birds, recent victims of plume hunters who had completely decimated the Cuthbert Rookery. There was no way one man could keep watch over the entire population of Florida's fowl no matter how dedicated that man might be.

On Saturday, July 8, 1905, Bradley noticed a sail on the horizon over Florida Bay. He watched as it moved toward Oyster Key and decided to investigate. A week later, Bradley's boat was found drifting near Cape Sable with Bradley's body inside. According to Walter Smith, a known poacher who was arrested soon after the body was discovered, Bradley's shooting was an act of self-defense. Smith claimed Bradley had attempted to arrest Smith and his son. When Smith resisted, Bradley shot at him and missed. Smith shot back and Bradley was killed. Although there was forensic proof Bradley's pistol had never been fired, no indictment was returned against Smith and he was released.

The Florida Audubon Society was outraged. In it's next issue of Bird-Lore, William Dutcher wrote of Bradley's senseless death. For what, he asks; for a few more plume birds to be secured "to adorn heartless women's bonnets? Heretofore the price has been the life of the birds, now is added human blood." Collier's called Bradley "Bird Protection's First Martyr." And even President Theodore Roosevelt sent his sympathies. Women's clubs around the country rose up against the use of plumes and encouraged others to follow suit.

On a ridge of shells overlooking Cape Sable, a stone was erected to honor the memory of the dedicated warden. It reads:

- :: GUY M. BRADLEY

- 1870-1905

- :: FAITHFUL UNTO DEATH

- AS GAME WARDEN OF MONROE COUNTY

- HE GAVE HIS LIFE FOR THE CAUSE

- TO WHICH HE WAS PLEDGED

- AS GAME WARDEN OF MONROE COUNTY

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |