Bagnold, Ralph A.

Ralph Alger Bagnold (1896-1990) is known for three intertwining achievements: military feats, desert exploration, and scientific contributions to geomorphology and sedimentology. His research publications on the movement of sediment by wind (Eolian processes and landforms) and water remain seminal references today.

Contents

Early Life

Ralph Bagnold was born in 1896 in Devon, in southwestern England. His mother was from a business family in Plymouth and his father was a Colonel in the Royal Engineers of the British Army. He had one sister, Enid, born six years before Ralph. As a child, he spent several years in Jamaica, but mostly grew up near London. His father encouraged an interest in engineering and young Ralph often built things out of items found around the home. A neighbor was an amateur scientist with a home laboratory who instilled in Ralph a curiosity for scientific knowledge. At thirteen, Ralph began at Malvern College, a well respected English public school, where he focused mainly on engineering and military studies.

First World War

In 1914, with the First World War about to begin, Bagnold joined the Army and became a lieutenant in the Royal Engineers. He served first in France, mostly overseeing the construction of battle trenches and maintaining bridges. Later he transferred to the Signal Corps in Flanders, laying and fixing telephone lines between battle zones and rear areas. He summed up his service as “[w]e lived a weird, other-worldly life among shell holes and rotting, fly-covered corpses. We got used to it. At my age I had known no other kind of adult life…. Our future seemed unlikely…. The majority of my friends gradually disappeared and were replaced by new faces.” (Bagnold, 1990, p. 198)

Between the Wars

At the end of the War, he took advantage of a program where officers could attend a university. He went to Cambridge, where he studied engineering, though he felt that his classes were too theoretically oriented. After graduating in 1921, he was stationed for two years in Ireland, which was in the often-violent process of transitioning to independence from British rule. He then spent several years home in England teaching in the Royal Corps of Signals.

Bagnold was stationed in Egypt in 1926. With much free time on their hands, he and some friends began to explore the region. They watched workmen carry away the sand that had buried the body of the Great Sphinx for millennia. They climbed many of the pyramids and Bagnold studied the irrigation works used on the Nile floodplain.

Impressed by a friend’s Model T Ford and its ability to travel over rough ground, Bagnold bought one for himself and they began to travel across the mostly roadless desert. Their first trips were to the east, to Suez, the Sinai, Palestine and the Transjordan. They learned much about desert travel by car, including how to drive over various types of terrain and how gasoline consumption varies under different types of driving conditions.

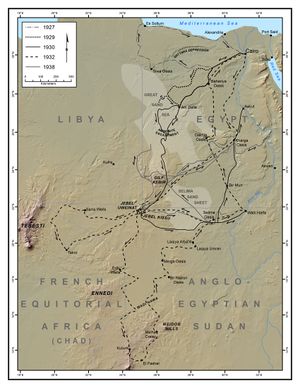

Then they turned their attention to the vast Libyan Desert west of the Nile. This desert had never been crossed in the east-west direction because its size and lack of water made it impossible for camels to survive the trek and the vast dune field known as the Great Sand Sea was assumed to be impenetrable by car. Their first trip west, in 1927, was to Siwa Oasis, returning via the coast. They did not drive in the dunes but the 1800 km round trip taught them more about desert travel.

For all of their trips, they not only had to plan the logistics of supplies and routes, but had to find a time when all could get leave from their duties and be able to scrape together enough money for gasoline and supplies. With each trip, they improved their detailed procedures for packing and safety and optimized daily rations of food and water. (For water, they allotted three pints (1.4 liter) per day for winter travel and five (2.4 liter) in the hotter months.) They became adept at getting stuck vehicles out of sand, improvising repairs in the field, and they modified the radiators so that water boiling out was saved for re-use.

Navigating with magnetic compasses proved difficult in bumpy steel vehicles, so Bagnold built a sun compass, improving on the design of previous versions. It was mounted on the dashboard and the shadow cast (by a knitting needle) could be seen because roofs were removed to reduce weight. The direction of the shadow and the known position of the sun over the course of the day (on reference tables they carried) allowed them to determine their bearing. The odometer gave the distance travelled.

Upon promotion to major in 1928, Bagnold was transferred to India, but continued to plan an expedition to the Libyan Desert. Bagnold was impressed with new Ford trucks and thought that they would work better than cars for desert travel. He bought one in India and he and two friends drove it to Egypt in 1929. After arriving and joining his travelling companions, their first journey to the dunes began. They drove 250 kilometers to the Great Sand Sea. Sometimes, they learned by taking chances, as in the first time they tried to drive over the large dunes:

I increased speed to forty miles an hour.... I saw Burridge holding on to the side of the lorry [truck] grimly. …A huge wall of yellow shot up high into the sky a yard in front of us. The lorry tipped violently backwards–and we rose as if in a lift, smoothly without vibration. All the accustomed car movements had ceased; only the speedometer told us we were still moving fast. It was incredible. Instead of sinking deep in loose sand at the bottom as instinct and experience both foretold, we were now near the top a hundred feet above the ground. Then the skyline receded disclosing a smooth blank surface of some sort, nearly level….

I cut the engine and let the car come to a rest gently to wait for the others…. Our wheel tracks behind were barely half an inch deep; they trailed out cleanly behind like a pair of railway lines. Yet the sand was quite soft; I ran my fingers through it easily, and there was no surface crust to support the wheels. It was just the special way the grains were packed. (Bagnold, 1935, p. 128-129)

Crossing the long, parallel ridges of sand was a skill to be used on later excursions. The trucks, however, proved to be too heavy and sunk into the ground and sand more than the lighter cars, so cars again became the preferred vehicle.

Their next trip was prepared and coordinated by Bagnold in India and his companions in England and Egypt. In 1930, they drove to the mountains known as Jebel Uweinat, near the intersecting borders of Egypt, Libya and Sudan. Losing two gear teeth on the transmission of Bagnold’s car led to its abandonment in the desert, after stripping it of tires and any other parts that might be needed by the remaining two cars. (As an aside, a short time later, a colleague of Bagnold’s brought tires and spare parts, found the car, fixed it and used it to save a group of nearly dead nomads who had fled an Italian occupation of their homeland hundreds of kilometers away.)

Bagnold spent most of his time in India, from 1928 to 1931, in the western portion that now is Pakistan. He did some travelling in the Himalayas, survived a bout of malaria and had a large skin cancer on his hand cured by two doses of X-rays.

From India, he returned to England and taught at the School of Signals. While looking at maps at the Royal Geographical Society, he happened to run into an old friend from Egypt and they began to plan for a 10,000 kilometer expedition in Egypt, Chad and Sudan (Chad was a territory of French Equatorial Africa at the time). On this 1932 expedition, they not only mapped their journey, but collected much natural history material (rocks, birds, plants, etc.) and archaeological artifacts in the region. The trip was the first crossing of the Libyan Desert from east to west. (By this time, they had replaced the Model T Fords with the new Model A cars.) Afterward, the Royal Geographical Society awarded Bagnold their Gold Medal for his contributions to exploration.

Bagnold and his companions were not the only group to explore the Libyan Desert by car in the 1920s and 1930s, but they pushed the boundaries of what was possible more than the others. While they did not operate under a rigid hierarchy, Bagnold was considered their leader. And they were quite competent in their adventures. As Bagnold (1935,p. 11-12) stated in the introduction to Libyan Sands: Travel in a Desert World, his book on the expeditions:

We never had a thrilling disaster. We never lost our way, or broke down, with only a dried date to live on…. We never went where we were not wanted, got shot up by angry tribesmen and provoked a reluctant Government into sending out police and troops. In short, we had no news value whatsoever, a most discouraging state of affairs from which to extract material for a Book of Travel, where tragedy or averted tragedy is so great an asset.

Bagnold spent 1933 and 1934 in East Asia, stationed in Hong Kong but travelling extensively. He returned to England after being diagnosed with tropical sprue, a disease of the intestines. The treatment consisted of weeks of almost no food and he was discharged from the Army as a “permanent invalid.”

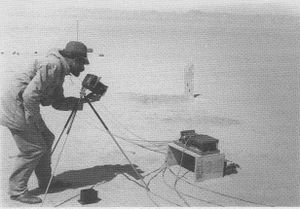

Fortunately, Bagnold recovered fully within a few months and turned his ample free time to scientific pursuits. His desert travels introduced him to sand dunes in their many forms and he was fascinated by their ability to maintain their shape as the sand on them moved. Certain kinds of dunes travelled across the desert and some even spawned other dunes. More basically, he wanted to understand the physical properties involved in the movement of sand grains by the wind. He built a wind tunnel at Imperial College in London, along with various devices for measuring wind speed inside a cloud of blowing sand. He applied what was known about fluid mechanics to the novel situation of air and solid particles flowing together. Bagnold developed a way to photograph sand grains bouncing along the surface and showed that sand rebounds higher off of a hard surface than a soft one, like a bed of other sand grains. He measured the distributions of sand grain size for hundreds of different situations (sand dunes, sea bed, streams) and introduced the practice of plotting the data logarithmically, which greatly aided the interpretation (and has been standard practice by sedimentologists ever since). He also found that the amount of sand moved by the wind is related to the cube of the wind speed and he developed an equation to predict the rate of sand transport.

His wind tunnel experiments needed field verification, so in 1938 Bagnold undertook another expedition. Sponsored by the Royal Geographical Society, he joined a group of archaeologists and set off for southwestern Egypt. While the rest of his party travelled elsewhere, Bagnold stayed alone for eight days with his equipment and measured wind speed and sand transport. His field data matched his laboratory findings reasonably well.

Bagnold published his findings in a pair of papers in the Proceedings of the Royal Society and wrote a book on his research. The Physics of Blown Sand and Desert Dunes was finished in 1939 and published in 1941. It remains a standard reference work and the inspiration for much of the research done today on sand transport by wind and sand dune studies.

In 1936, Bagnold travelled to Japan as the general handyman for an astronomical expedition to collect data during a solar eclipse. On his way home, he detoured to Tanganyika (now Tanzania) and joined a friend to climb Mt. Kilimanjaro.

Second World War

When war broke out again in 1939, Bagnold was back in the Army. He was posted to East Africa but his ship had an accident in the Mediterranean and stopped in Egypt for repairs. With some free time, he went to Cairo. A journalist recognized him and wrote an article praising the War Office for bringing such an experienced soldier back to Egypt. The Army then realized that Bagnold should be in Egypt and had him reassigned.

The British Army in Egypt was small relative to the Italian Army in Libya. Bagnold proposed that he develop a unit that could travel quickly over long distances to collect intelligence and commit “acts of piracy” if such opportunities arose. He was given six weeks to put the unit together and started by getting several friends from his previous desert travels to join him. They acquired thirty Chevrolet one and a half ton trucks and had them modified for desert travel. One hundred and fifty New Zealand soldiers volunteered for the unit and their felt hats and boots were replaced by far more practical Arab headdresses and sandals. They were taught how to move the trucks over difficult terrain and how to navigate in the desert. An initial excursion into Libya showed that they could be successful and the size of the unit was doubled. They became known as the Long Range Desert Group, led by Lieutenant Colonel R. A. Bagnold.

The Italians were beginning an invasion of Egypt, which if successful would have given them control of the Suez Canal and a path into the Middle East. However, numerous LRDG attacks on their outposts fooled them into thinking that the British forces were stronger than anticipated and the invasion was delayed. This operation has been called “Bagnold’s Bluff” and it gave the British time to strengthen their forces and better prepare for battle. The LRDG continued operations against the Italian and German armies until the end of the North Africa Campaign in 1943. Over time, Bagnold returned to Signal Corps duty and leadership of the LRDG went to Guy Prendergast, one of his companions on the earlier exploring trips. Bagnold was promoted to Brigadier, a rank between Colonel and General. In addition, in 1941 he became a member of the Order of the British Empire for his military accomplishments.

Post War

In 1944, Bagnold’s father died and he was given permission to leave the Army and see to family business affairs. On returning to England, he was pleasantly surprised to find that he had been elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society, a high honor for British scientists. He often visited his sister Enid, who was a well-known novelist and playwright, best known for the children’s book National Velvet. At Enid’s home, he met Dorothy Plank and the two married in 1946. The next year their son Stephen was born and daughter Jane soon followed. In the late 1940s, he worked as Director of Research for a subsidiary of Shell Oil, but quit to get back to research on topics he chose.

Bagnold began a series of experiments and theoretical work on the transport of soil particles in water with the long-term goal of understanding sediment movement in streams. This research was a natural outgrowth of his work with sediment movement by wind. He abandoned conventional thinking on the topic and reasoned from basic physical principles how solid particles ought to move in water, based on the amount of energy in the water. In 1956, he began corresponding with Luna Leopold of the U. S. Geological Survey. Both saw the need for an accurate means of predicting sediment movement in streams based on the underlying physics of the process. In 1958, Bagnold began working as a consultant to the USGS, spending part of each year in the United States. The USGS built a hydraulics laboratory for research on sediment movement and Bagnold outlined a series of experiments where one variable could be altered at a time. Simply put, they found that sediment movement is proportional to stream energy and flow depth.

To test their laboratory results under natural conditions, they modified a stream in Wyoming. A conveyor belt was built across the steam bed so that all sediment moving along the bottom would be caught and brought to the bank for later weighing and other measurements. Analyses of sediment data collected at different stream discharges generally confirmed the laboratory findings. Studies of sediment data from streams around the world also generally conformed to Bagnold’s theory. (It should be noted that truly accurate estimations of sediment transport by streams remain elusive today, but the work of Bagnold and his collaborators at the USGS was a tremendous improvement in our understanding of the underlying processes involved. The same is true of sediment movement by wind.)

Bagnold continued publishing research articles in prestigious scientific journals through the 1980s. In 1990, at age 94, he contracted pneumonia and died peacefully in his sleep.

Along with his positions as Fellow of the Royal Society and Order of the British Empire, Bagnold received major awards for his scientific contributions from the US National Academy of Sciences, both theGeological Society of America and the Geological Society of London, and the International Association of Sedimentologists. He summed up his ability to make novel scientific contributions in this way: “Being an amateur, a free lance who had never held any academic post or had any professional status, I had the rather unusual advantage of considering problems with an open mind, unbiased by traditional textbook ideas that remained untested against facts. I had the further advantage that the sort of problems that interested me did not involve expensive or elaborate apparatus. I could design and make what I needed.” (Bagnold, 1990, p. 199-200)

Ralph Bagnold made major contributions in three endeavors: military, exploration and scientific. But the three merged together. His military career gave him the opportunity to explore unknown regions. His geographical explorations sparked his interest in understanding the landscapes he travelled through and his move to scientific studies, he felt, was as another means of exploration. His exploration and science studies then guided his military contributions, through the LDRG.

References

- Bagnold, Stephen, personal communication, June 2011.

- Bagnold, R.A., 1933. A Further Journey Through the Libyan Desert. The Geographical Journal, v. 82 no. 2, p. 103-126.

- Bagnold, Ralph A., 1935. Libyan Sands: Travel in a Dead World, Michael Haag Limited, London. (Reprinted in 2011, Eland Press.)

- Bagnold, Ralph A., 1990. Sand, Wind and War: Memoirs of a Desert Explorer, University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

- Bagnold, R.A. and Harding King, W.J., 1931. Journeys in the Libyan Desert 1929 and 1930. The Geographical Journal, v. 78 no. 6, p. 524-535.

- Bagnold, R.A., Myers, O.H., Peel, R.F. and Winkler, H.A., 1939. An Expedition to the Gilf Kebir and ‘Uweinat, 1938. The Geographical Journal, v. 93 no. 4, p. 281-312.

- Constable, T.J., 1999, Bagnold’s Bluff. The Journal for Historical Review, v. 18 no. 2.

- Goudie, Andrew, 2008. Wheels Across the Desert: Exploration of the Libyan Desert by Motorcar 1916-1942, Silphium Press, London.

- Kenn, Maurice J., 1991. Ralph Alger Bagnold, Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society, v. 37, p. 56-68.