Anthrax

Contents

- 1 Introduction (Anthrax)

- 1.1 U.S. Geological Survey

- 1.2 U.S. Department of Agriculture

- 1.3 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- 1.3.1 What is anthrax?

- 1.3.2 How common is anthrax and who can get it?

- 1.3.3 How is anthrax transmitted?

- 1.3.4 What are the symptoms of anthrax?

- 1.3.5 Where is anthrax usually found?

- 1.3.6 Can anthrax be spread from person-to-person?

- 1.3.7 Is there a way to prevent infection?

- 1.3.8 What is the anthrax vaccine?

- 1.3.9 Who should get vaccinated against anthrax?

- 1.3.10 What is the protocol for anthrax vaccination?

- 1.3.11 Are there adverse reactions to the anthrax vaccine?

- 1.3.12 How is anthrax diagnosed?

- 1.3.13 Is there a treatment for anthrax?

- 1.3.14 Where can I get more information about the recent Department of Defense decision to require men and women in the Armed Services to be vaccinated against anthrax?

- 2 References

- 3 Further Reading

Introduction (Anthrax)

U.S. Geological Survey

Wildlife Health Connection to Emerging Infectious Diseases

"Wildlife, domestic animals and humans share a large and increasing number of infectious diseases. The continued globalization of society, human population growth (Human population explosion), and associated landscape changes will further enhance interfaces between wildlife, domestic animals, and humans, thereby facilitating additional infectious disease emergence. These interfaces are such that a century-old concept of “the one medicine” is receiving greater attention because of the need to address these diseases across species if their economic, social, and other impacts are to be effectively minimized. The wildlife component of this triad has received inadequate focus in the past to effectively protect human health as evidence by such contemporary diseases as SARS, Lyme disease, West Nile Fever, and a host of other emerging diseases. Further, habitat loss and other factors associated with human-induced landscape changes have reduced past ability for many wildlife populations to overcome losses due to various causes. This, disease emergence and resurgence has reached unprecedented importance for the sustainability of desired population levels for many wildlife populations and for the long-term survival of some species"[1]

U.S. Department of Agriculture

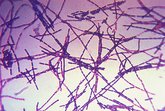

The U.S. Department of Agriculture's Food Safety and Inspection Service characterizes Anthrax as a disease of mammals and humans caused by a spore-forming bacterium called Bacillus anthracis. Anthrax has an almost worldwide distribution and is a zoonotic disease, meaning it may spread from animals to humans. All mammals appear to be susceptible to anthrax to some degree, but ruminants such as cattle, sheep, and goats are the most susceptible and commonly affected, followed by horses, and then swine.

The U.S. Department of Agricultures (USDA) main diagnostics laboratory in Ames, Iowa, the National Veterinary Services Laboratories (NVSL), maintains small quantities of anthrax to use as reference material in making confirmatory anthrax diagnoses in animals.

Disease Epidemiology

Anthrax is endemic to the United States, occurring sporadically throughout the country as environmental conditions allow. The Del Rio, Texas, region has reported ongoing outbreaks of anthrax in deer and livestock this summer. The most recent outbreak there occurred on Sept. 21, 2001. Other recent outbreaks include an outbreak in cattle and horses in Minnesota in June-July 2000; in cattle, horses, and bison in North Dakota in August 2000; and in cattle in Nebraska in January 2001.

During their vegetative stage, cells of the anthrax agent multiply in the lymph nodes of susceptible animals, including humans. When cells of B. anthracis escape from the animal's body and are exposed to oxygen, they form spores. These spores are highly resistant to heat, cold, chemical disinfectants, and long dry periods. B. anthracis spores are reported to survive for years in the environment. Environmental persistence may be related to a number of factors, including high levels of soil nitrogen and organic content, alkaline soil (a pH level higher than 6.0), and ambient temperatures higher than 60 degrees Fahrenheit.

The anthrax organism may be spread within an area by streams, insects, wild animals and birds, and contamination from wastes of infected animals. Anthrax may be perpetuated in nature by hosts such as a wildlife reservoir, which in turn spills over into the livestock population. Animals are usually infected by ingesting soilborne spores, such as in contaminated food or water. Spores can be picked up directly from the soil through grazing or from feed grown on infected soil. When periods of drought cause livestock to forage much closer to the ground, animals may ingest spores in soil they accidentally eat along with forage. After flooding, the concentration of spores caught in standing water increases when preexisting or transitory ponds begin to evaporate.

Although rare, it is possible for animals to inhale dust harboring anthrax spores. Bites from flies and other insects that may harbor vegetative anthrax have also been reported to be vehicles for mechanical transmission.

Clinical Signs

Disease occurs when spores enter the body, germinate, multiply, and release toxins. The incubation period of natural infection in animals is typically 3 to 7 days with a range of 1 to 14 days, or more.

In cattle and sheep, the course of illness may last about 1 to 2 hours. Clinical signs, such as fever up to 107 degrees Fahrenheit, muscle tremors, respiratory distress, and convulsions, often go unnoticed. After death, there may be bloody discharges from the natural openings of the body, rapid bloating, a lack of rigor mortis, and the presence of unclotted blood. This failure of blood to clot is due to a toxin released by B. anthracis.

Anthrax in horses and related animals is acute and can last up to 96 hours. Clinical manifestations depend upon how the infection occurred. If due to ingestion of spores, as in cattle, septicemia, fever, colic, and enteritis are prominent. Anthrax due to insect bite introduction (mechanical transmission) is characterized by localized hot, painful, edematous, and subcutaneous swellings at the bite location that spread to the throat, lower neck, floor of the thorax, abdomen, prepuce, and mammary glands. These horses may have a high fever and dyspnea due to swelling of the throat or colic due to intestinal involvement.

Swine, dogs, and cats usually show a characteristic swelling of the neck secondary to regional lymph node involvement, which causes dysphagia and dyspnea following ingestion of the bacteria. An intestinal form of anthrax with severe enteritis sometimes occurs in these species. Many carnivores apparently have a natural resistance, and recovery is not uncommon.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has prepared answers to frequently asked questions about Anthrax, and about the organism that causes this disease:

What is anthrax?

Anthrax is an acute infectious disease caused by the spore-forming bacterium Bacillus anthracis. Anthrax most commonly occurs in wild and domestic lower vertebrates (cattle, sheep, goats, camels, antelopes, and other herbivores), but it can also occur in humans when they are exposed to infected animals or tissue from infected animals.

How common is anthrax and who can get it?

Anthrax is most common in agricultural regions where it occurs in animals. These include South and Central America, Southern and Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, the Caribbean, and the Middle East. When anthrax affects humans, it is usually due to an occupational exposure to infected animals or their products. Workers who are exposed to dead animals and animal products from other countries where anthrax is more common may become infected with B. anthracis (industrial anthrax). Anthrax in wild livestock has occurred in the United States.

How is anthrax transmitted?

Anthrax infection can occur in three forms:

- cutaneous (skin);

- inhalation; and

- gastrointestinal.

B. anthracis spores can live in the soil for many years, and humans can become infected with anthrax by handling products from infected animals or by inhaling anthrax spores from contaminated animal products. Anthrax can also be spread by eating undercooked meat from infected animals. It is rare to find infected animals in the United States.

What are the symptoms of anthrax?

Symptoms of disease vary depending on how the disease was contracted, but symptoms usually occur within 7 days.

- Cutaneous: Most (about 95%) anthrax infections occur when the bacterium enters a cut or abrasion on the skin, such as when handling contaminated wool, hides, leather or hair products (especially goat hair) of infected animals. Skin infection begins as a raised itchy bump that resembles an insect bite but within 1-2 days develops into a vesicle and then a painless ulcer, usually 1-3 cm in diameter, with a characteristic black necrotic (dying) area in the center. Lymph glands in the adjacent area may swell. About 20% of untreated cases of cutaneous anthrax will result in death. Deaths are rare with appropriate antimicrobial therapy.

- Inhalation: Initial symptoms may resemble a common cold. After several days, the symptoms may progress to severe breathing problems and shock. inhalation anthrax is usually fatal.

- Intestinal: The intestinal disease form of anthrax may follow the consumption of contaminated meat and is characterized by an acute inflammation of the intestinal tract. Initial signs of nausea, loss of appetite, vomiting, fever are followed by abdominal pain, vomiting of blood, and severe diarrhea. Intestinal anthrax results in death in 25% to 60% of cases.

Where is anthrax usually found?

Anthrax can be found globally. It is more common in developing countries or countries without veterinary public health programs. Certain regions of the world (South and Central America, Southern and Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, the Caribbean, and the Middle East) report more anthrax in animals than others.

Can anthrax be spread from person-to-person?

Anthrax is not known to spread from one person to another person. Communicability is not a concern in managing or visiting with patients with inhalation anthrax.

Is there a way to prevent infection?

In countries where anthrax is common and vaccination levels of animal herds are low, humans should avoid contact with livestock and animal products and avoid eating meat that has not been properly slaughtered and cooked. Also, an anthrax vaccine has been licensed for use in humans. The vaccine is reported to be 93% effective in protecting against anthrax.

What is the anthrax vaccine?

The anthrax vaccine is manufactured and distributed by BioPort, Corporation, Lansing, Michigan. The vaccine is a cell-free filtrate vaccine, which means it contains no dead or live bacteria in the preparation. The final product contains no more than 2.4 mg of aluminum hydroxide as adjuvant. Anthrax vaccines intended for animals should not be used in humans.

Who should get vaccinated against anthrax?

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices has recommended anthrax vaccination for the following groups:

- Persons who work directly with the organism in the laboratory

- Persons who work with imported animal hides or furs in areas where standards are insufficient to prevent exposure to anthrax spores.

- Persons who handle potentially infected animal products in high-incidence areas. (Incidence is low in the United States, but veterinarians who travel to work in other countries where incidence is higher should consider being vaccinated.)

- Military personnel deployed to areas with high risk for exposure to the organism (as when it is used as a biological warfare weapon).

The Anthrax Vaccine Immunization Program in the U.S. Army Surgeon General's Office can be reached at 1-877-GETVACC (1-877-438-8222).

Pregnant women should be vaccinated only if absolutely necessary.

What is the protocol for anthrax vaccination?

The immunization consists of three subcutaneous injections given 2 weeks apart followed by three additional subcutaneous injections given at 6, 12, and 18 months. Annual booster injections of the vaccine are recommended thereafter.

Are there adverse reactions to the anthrax vaccine?

Mild local reactions occur in 30% of recipients and consist of slight tenderness and redness at the injection site. Severe local reactions are infrequent and consist of extensive swelling of the forearm in addition to the local reaction. Systemic reactions occur in fewer than 0.2% of recipients.

How is anthrax diagnosed?

Anthrax is diagnosed by isolating B. anthracis from the blood, skin lesions, or respiratory secretions or by measuring specific antibodies in the blood of persons with suspected cases.

Is there a treatment for anthrax?

Doctors can prescribe effective antibiotics. To be effective, treatment should be initiated early. If left untreated, the disease can be fatal.

Where can I get more information about the recent Department of Defense decision to require men and women in the Armed Services to be vaccinated against anthrax?

The Department of Defense recommends that servicemen and women contact their chain of command on questions about the vaccine and its distribution. The Anthrax Vaccine Immunization Program in the U.S. Army Surgeon General's Office can be reached at 1-877-GETVACC (1-877-438-8222).