Antarctic minke whale

The Antarctic minke whale (scientific name: Balaenoptera bonaerensis), is a very large marine mammal, in the family of Rorquals (Balaenoptera), part of the order of cetaceans. The Minke is a baleen whale, meaning that instead of teeth, it has long plates which hang in a row (like the teeth of a comb) from its upper jaws. Baleen plates are strong and flexible; they are made of a protein similar to human fingernails. Baleen plates are broad at the base (gumline) and taper into a fringe which forms a curtain or mat inside the whale's mouth. Baleen whales strain huge volumes of ocean water through their baleen plates to capture food: tons of krill, other zooplankton, crustaceans, and small fish.

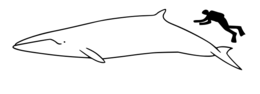

Size comparison of an average human and a minke whale. Source: Chris Huh Size comparison of an average human and a minke whale. Source: Chris Huh

|

|

Conservation Status |

|

Scientific Classification Kingdom: Animalia |

Contents

Physical Description

Balaenoptera bonaerensis is among the smallest rorqual species. Mature males average 8.36 m ineters (m) length and weigh 6.85 tons, but an adult reach a total length of 9.63 m and a body mass of 11.05 tons. Females are slightly longer with a mean total length of 7.57 m and a maximum measured length of 10.22 m. On average, B. bonaerensis is slightly longer than all forms of B. acutorostrata. Similar to Balaenoptera acutorostrata, Antarctic minke whales are dark grey on the back with a pale ventral side. The main recognition character that allows for the distinction of Antarctic minke whales from Balaenoptera acutorostrata is the absence of a white patch on the flippers in Antarctic minke whales. The rostrum is narrow and pointed. The dorsal fin is hook-shaped and located about two-thirds the length of the body from the anterior. Baleen plates are black on the left side and on the posterior two thirds of the right side, while the remaining baleen plates are white. The baleen plate filaments average about 3.0 mm in diameter. Antarctic minke whales have larger skulls than Balaenoptera acutorostrata. (Konishi et al., 2008; Perrin and Brownell Jr, 2002)

Behavior

Minke whales in Antarctic feeding areas can be solitary or form small groups. They are generally seen in groups of two to four individuals. Distribution of individuals within these groups is relatively random. There seems to be an enhanced amount of clustering in relatively enclosed areas (e.g., bays) as opposed to open water habitats. Antarctic minke whales sometimes uses the rostrum to break ice several centimeters in thickness to create breathing holes. The distance between two neighboring holes usually ranges from 200 m to 300 m. The species is often said to actively avoid ships that are in motion; furthermore, it uses “porpoising” behavior in doing so.

However, minke whales are also notorious for their curiosity and are one of the most frequently observed Balaenoptera because of their habit of approaching stationary boats. Fleeing behavior is not as commonly observed in the pack ice. Antarctic minke whales are fast swimmers, capable of speeds up to 20 km/hr. They typically dive for two to six minutes, with one minute at the surface during which they blow five to eight times. They can dive for up to 20 minutes. Minke whales breach more often than other Mysticeti. Most populations seem to migrate between summer and winter grounds, but some populations appear to remain in Antarctic waters throughout the year. (Ainley et al., 2007; Kasamatsu, Ensor, and Joyce, 1998; Schueller, 2004)

Voice and Sound Production

Balaenoptera acutorostrata in the North Atlantic produces an extensive array of sounds. Mellinger and Carson (2000) analyzed pulse trains of minke whales in the Caribbean and classified them into two categories: the “speed-up” trains and the less common “slow-down” trains. Pulse trains are sequences of pulses produced at regular or irregular intervals. There is limited information, however, as to whether this type of vocalization is also present in B. bonaerensis and what function it serves in B. acutorostrata. (Mellinger and Carson, 2000)

Reproduction

Key reproductive features of the species are: Iteroparous; seasonal breeding; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual mating; viviparous birth. Lucena (2006) suggested that Antarctic minke whales are polygamous, judging by the structure of groups in breeding grounds. Little is known about mating behavior in any Balaenoptera. (Lucena, 2006)

Kasamatsu et al. (1995) found that minke whales (probably Balaenoptera bonaerensis) migrate far north but their main breeding areas are probably between 10º and 20º S. Breeding populations may be relatively dispersed and do not seem to be associated with the coast. The generation time is estimated to be about 22 years. (Kasamatsu, Nishiwaki, and Ishikawa, 1995)

Antarctic minke whales, like Balaenoptera acutorostratus, have a gestation period of ten months, after which a single young is born at about 2.7 meters long. Calves stay with their mother for up to two years and may nurse for three to six months. (Schueller, 2004)

In Antarctic minke whales, the age at which sexual maturity is reached has been shown to have decreased from an average of age 11 in the cohorts of 1950’s to about seven years old in the 1970’s cohorts. (Thomson, Butterworth, and Kato, 1999) Antarctic minke whale females can breed up to every year, although it is more common for them to breed less often. It is thought that the breeding season occurs during the austral summer.

Female Antarctic minke whales gestate, nurse, and protect their young for up to two years. Males do not provide parental care. The milk of their close relatives, Common minke whales (Balaenoptera acutorostrata), contains lactose and several other oligosaccharides, some of which have never been found in any other mammalian species. These new oligosaccharides may have a function in the immunity of the neonate. (Saito et al., 2002)

Lifespan/Longevity

In an 18-year study of energy storage in Antarctic minke whales, Konishi et al. (2008) aged a total of 4,268 mature whales (mature males and pregnant females). They used measurement of the earplug, a layered keratinized and fatty structure inside the external auditory canal, to determine age. The oldest whale aged in their study was 73 years old according to this technique. (Konishi et al., 2008; Lockyer, 1972)

Distribution and Movements

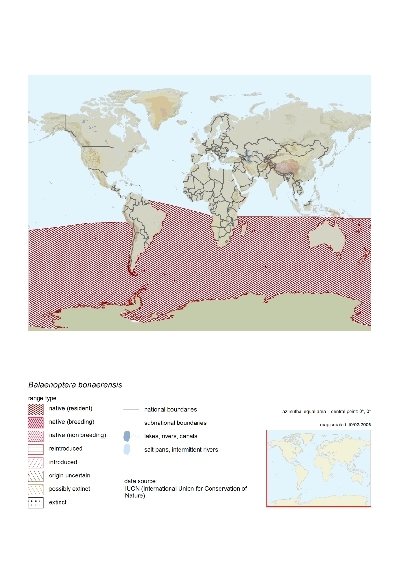

Balaenoptera bonaerensis occurs in polar to tropical waters of the southern hemisphere. It occurs in large numbers south of 60º S, throughout the Antarctic. The distribution is more difficult to assess north of the Antarctic because of its co-occurrence with Balaenoptera acutorostrata. As a result, the boundaries of the species winter distributions remain largely undefined. Balaenoptera bonaerensis is observed off the coast of Brazil and South Africa and there have been occasional sightings in Peru. An unknown proportion of the species remains in Antarctic waters during the winter. (Mead and Brownell Jr, 2005)

Habitat

Balaenoptera bonaerensis can be found in marine waters from polar to tropical regions, generally within 160 km of the edge of pack ice. While mostly found at the ice edge, B. bonaerensis can also be found within the pack ice and in polynyas. Association with pack ice is especially pronounced during winter. (Friedlaender et al., 2004; Mead and Brownell Jr, 2005; Schueller, 2004)

Food and Feeding Habits

Antarctic minke whales feed mainly on krill (Euphausia superba). Euphausia superba comprises 100% of stomach contents of minke whales caught at the ice edge and 94% (by weight) of the stomach contents of minke whales in the offshore zone. Euphausia crystarollophias was also found in smaller quantities in the stomachs of Antarctic minke whales caught in coastal areas. Other prey include Euphasi frigida and Thysanoessa macrura. This is in contrast to Balaenoptera acutorostrata, which feed on a more diverse array of fish and invertebrates. Antarctic minke whales feed primarily in the early morning and late evening and most feeding activity is observed at the edge of pack ice. Daily food consumption in the summer was estimated at 3.6 to 5.3% of body weight, representing an important proportion of krill biomass in the study area. It is likely that Antarctic minke whales eat much smaller quantities of food during the austral winter or perhaps forage very little at all on wintering grounds (Best 1982 as cited in Reilly et al., 2008). The blubber layer thickens as the feeding season progresses but mean blubber thickness in individuals has decreased over the 18 year period between 1987 and 2005. This might suggest a decrease in food availability in Antarctic waters. (Ichii and Kato, 1991; Konishi et al., 2008; Reilly et al., 2008; Tamura and Konishi, 2006)

Economic Importance for Humans

There are no recognized direct negative impacts of Antarctic minke whales on human populations. One could hypothesize, however, that potential food competition with other economically important whale species, such as blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus), could have a negative economic impact on their harvest. Larger whale species are considered more valuable in that they provide more meat per unit catch.

Since 1986, commercial whaling has been prohibited by the International Whaling Commision. Balaenoptera bonaerensis is currently taken for scientific whaling by the Japanese. The animals caught in that process can then be sold on the market for food. Before the decline of larger whale species, such as fin and blue whales (Balaenoptera physalus and Balaenoptera musculus, respectively), B. bonaerensis was seldomly targeted by whalers due to its comparatively smaller size. Consequently, whaling on Antarctic minke whales has only started relatively recently, since 1971 (IWC 2006 as cited in Reilly et al., 2008). (Reilly et al., 2008)

Threats and Conservation Status

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) currently lists the species as “Data Deficient”. However, it has been suggested that the species has declined by about 60% between the periods 1978–91 and 1991–2004. If the decline is shown to be an artifact or to have been transient, the species would then be classified as “Least Concern”, whereas it would be classified as “Endangered” if it was demonstrated to be an actual decline. The Peru population was added to Appendix I of CITES in 1986 and withdrawn from it in 2001. The predicted substantial decline in the extent of Antarctic sea ice may dramatically effect krill populations and the Antarctic minke whale populations that depend on them. (Reilly et al., 2008)

References

- Balaenoptera bonaerensis, Encyclopedia of Life (accessed February 17, 2011)

- Balaenoptera bonaerensis, IUCN Redlist (accessed February 15, 2011)

- Ainley, D., K. Dugger, V. Toniolo, I. Gaffney. 2007. Cetacean occurences patterns in the Amundsen and southern Bellingshausen sea sector, Soutern Ocean. Marine Mammal Science, 23(2): 287-305.

- UCN (2008) Cetacean update of the 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- Ichii, T., H. Kato. 1991. Food and daily food consumption of southern minke whales in the Antarctic. Polar Biology, 11: 479-487.

- Iwayama, H., H. Ishikawa, S. Ohsumi, Y. Fukui. 2005. Attempt at in vitro maturation of minke whale (Balaenoptera bonaerensis) oocytes using a portable CO2 incubator. Journal of Reproduction and Development, 51(1): 69-75.

- Kasamatsu, F., P. Ensor, G. Joyce. 1998. Clustering and aggregations of minke whales in the Antarctic feeding grounds. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 168: 1-11.

- Kasamatsu, F., S. Nishiwaki, H. Ishikawa. 1995. Breeding areas and southbound migrations of southern minke whales Balaenoptera acurostrata. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 119: 1-10.

- Konishi, , Tamura, Zenitani, Bando, Kato, Walloe. 2008. Decline in energy storage in the Antarctic minke whale (Balaenoptera bonaerensis) in the Southern Ocean. Polar Biology, 31(12): 1509-1520.

- Lockyer, C. 1972. The age at sexual maturity of the southern fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) using annual layer counts in the ear plug. Journal du Conseil International pour l’Exploration de la Mer, 34(2): 276-294.

- Lucena, A. 2006. Minke whale Balaenoptera bonaerensis (Burmeister)(Cetacea, Balaenopteridae) population structure in the breeding grounds off South Atlantic Ocean. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia, 23(1): 176-185

- Mead, J., R. Brownell Jr. 2005. Order Cetacea. Pp. 2142 in D.E. Wilson, D.M. Reeder, eds. Mammal Species of the World. A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd Ed.). Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

- Mead, James G., and Robert L. Brownell, Jr. / Wilson, Don E., and DeeAnn M. Reeder, eds. 2005. Order Cetacea. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 3rd ed., vol. 1. 723-743

- Mellinger, D., C. Carson. 2000. Characteristics of minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata) pulse trains recorded near Puerto Rico. Marine Mammal Science, 16(4): 739-756.

- Pastene, L., M. Goto, N. Kanda, A. Zerbini, D. Kerem. 2007. Radiation and speciation of pelagic organisms during periods of global warming: the case of the common minke whale, Balaenoptera acutorostrata. Molecular Ecology, 16: 1481-1495.

- Perrin, W. 2010. Balaenoptera bonaerensis Burmeister, 1867. In: Perrin, W.F. World Cetacea Database. Accessed through: Perrin, W.F. World Cetacea Database at http://www.marinespecies.org/cetacea/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=231405 on 2011-02-05

- Perrin, W., R. Brownell Jr. 2002. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. San Diego: Academic Press.

- Pitman, R., P. Ensor. 2003. Three forms if killer whales (Orcinus orca) in Antarctic waters. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management, 5(2): 131-139.

- Reilly, S., J. Bannister, P. Best, M. Brown, R. Brownell Jr, D. Butterworth, P. Clapham, J. Cook, G. Donovan, J. Urbán, A. Zerbini. 2008. Balaenoptera bonaerensis (On-line). 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed February 05, 2009 at http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/2480 .

- Rice, Dale W. 1998. Marine Mammals of the World: Systematics and Distribution. Special Publications of the Society for Marine Mammals, no. 4. ix + 231

- Schueller, G. 2004. Rorquals (Balaenopteridae). Pp. 119-130 in M. Hutchins, A.V. Evans, J.A. Jackson, D.A. Kleiman, J.B. Murphy, D.A. Thoney, eds. Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia, Vol. Vol. 15: Mammals IV., 2nd ed Edition. Detroit: The Gale Group.

- Tamura, T., K. Konishi. 2006. Feeding habits and prey consumption of Antarctic minke whales, Balaenoptera bonaerensis in JARPA research area.

- Tetsuka, M., M. Asada, T. Mogoe, Y. Fukui, H. Ishikawa, S. Ohsumi. 2004. The Pattern of Ovarian Development in the Prepubertal Antarctic Minke Whale (Balaenoptera bonaerensis). Journal of Reproduction and Development, 50(4): 381-389.

- Thiele, D., E. Chester, S. Moore, A. Sirovic, J. Hidlebrand, A. Friedlaender. 2004. Seasonal variability in whale encounters in the Western Antarctic Peninsula. Deep-Sea Research Part II - Tropical Studies in Oceanography, 51(17-19): 2311-2325.

- Thomson, R., D. Butterworth, H. Kato. 1999. Has the age at transition of Southern Hemisphere minke whales declined over recent decades?. Marine Mammal Science, 15(3): 661-682.

- UNESCO-IOC Register of Marine Organisms

- Urashima, T., H. Sato, J. Munakata, T. Nakamura, I. Arai, T. Saito, M. Tetsuka, Y. Fukui, H. Ishikawa, C. Lydersen, K. Kovacs. 2002. Chemical characterization of the oligosaccharides in beluga (Delphinapterus leucas) and Minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata) milk. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology B-Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 132(3): 611-624.

- Àrnason, U., A. Gullberg, B. Widegren. 1993. Cetacean mitochondrial DNA control region: sequences of extant baleen whales and two sperm whales species. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 10: 960-970.

1 Comment

Greg Osmond wrote: 05-10-2013 17:42:16

I was watching two Minke whales for one hour today near my home in Woody Point, Newfoundland and one kept turning with its white side up and the other seemed much smaller. Does anyone have any suggestions as to what they were doing? I thought maybe it was either a sexual thing or maybe breast feeding the younger one? Any ideas would be welcome!! Greg Osmond May 10. 2013.