Africa's renaissance for the environment: biodiversity

Contents

Issues

Africa’s biodiversity wealth is an important feature of its environment. Biodiversity plays a role in poverty reduction through contributions to food security, health improvement, income generation, reduced vulnerability to climate change and provision of ecosystem services such as the cycling of nutrients and the replenishment of soil fertility. This wealth of biodiversity is unevenly distributed throughout Africa. South Africa, for example, has over 23,000 plant species, compared to Cameroon’s approximately 8,260 species and Kenya’s 6,500 species. Some African countries, such as Madagascar, the DRC and Cameroon, are known for their rare internationally recognized plant and animal species. Some of Africa’s plant species have also contributed immensely to the world’s pharmaceutical industry. Noteworthy among these are Ancistrocladus korupensis (Cameroon), Pausinystalia yohimbe (Nigeria, Cameroon and Rwanda) and Catharanthus roseus (Madagascar), which are being used in pharmaceutical research in industrialized countries. This also is the case in Botswana and South Africa, where indigenous peoples’ and rural communities’ knowledge and use of a cactus-like succulent (Hoodia gordonii) has become the basis for substantial investment in developing a dietary drug.

There are, of course, microbial and other species that offer potential for scientific development in agriculture and medicine.

The diversity of fish species includes some of the most economically significant species such as Thunnus thynnus (tuna), Tetrapturus albidus (white marlin), Makaira indica (black marlin) and Istiophorus albicans (billfish). In countries such as Namibia the fisheries sector contributes substantially to both gross domestic product (GDP) (over 35 percent) and employment. The Eastern Afromontane Hotspot is an extremely important area for freshwater fish diversity, with more than 620 endemic species.

Africa’s dryland ecosystems are also rich in biodiversity. Although the diversity of species in the drylands is quantitatively lower than in other ecosystems, that diversity is marked by its tremendous qualitative value. There are exceptions to this: some areas with harsh climates including the Namib Desert and the Karoo in the west of South Africa have an estimated 4,500 plant species, a third to one-half of which are endemic. The ecological conditions within drylands require species to become resilient or tolerant to drought and salinity, to be able to grow readily and to set seeds within a very short time frame. Such genetic traits are of global value and are particularly important to populations living in drylands. Some of the plant species in the drylands of Ethiopia and Madagascar, for instance, are valuable alternative food sources during drought.

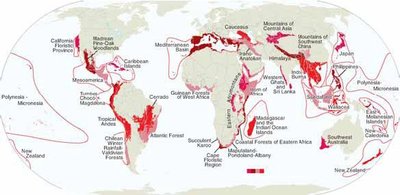

Overall, Africa is home to eight of the 34 internationally recognized biodiversity hotspots in the world. These are the Cape Floristic Region, Coastal Forests of Eastern Africa, Eastern Afromontane, Guinean Forests of West Africa, the Horn of Africa, Madagascar and the Indian Ocean Islands, Maputaland-Pondoland-Albany and the Succulent Karoo.

Biodiversity has influenced the culture and development in the region over centuries. There is a correlation between centres of biodiversity richness and human settlement. Historically, biodiversity has been at the core of livelihoods, and this remains true for many peoples, especially those who have maintained a traditional lifestyle, including forest dwellers in the Congo basin and the nomadic peoples of Eastern Africa and Southern Africa. At the regional level, biodiversity has played an important role in food security by ensuring the availability of a genetic base for improved local varieties, both crops and animals. In the tourism sector, which is a major income earner for many countries in the region, it is the foundation on which tourism is built. These resources are also supporting vibrant fisheries and pharmaceutical industries.

Disturbance and loss of habitat has, however, resulted in the loss of species and, combined with agricultural practices which focus on a few crops, is narrowing the genetic base. The impact of genetic modification of these resources remains uncertain. Invasive alien species pose a significant threat to biodiversity and to the survival of many native species, causing substantial economic losses and threatening livelihoods. The erosion of Africa’s biodiversity wealth arising from human activities is a serious problem. In the 1990s threats to higher plants included the known loss of 67 species in Cameroon, 69 in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), 125 in Ethiopia, 130 in Kenya, 255 in Madagascar, 326 in Tanzania, and 1,875 in South Africa. In response, African governments have, among other things, established protected areas, of which there are, for instance, 405 in South Africa, 68 in Kenya, 54 in Uganda, 45 in Madagascar and 39 in Ethiopia. In some countries, the management of the protected areas has not been effective because of the tendency to focus heavily on biodiversity protection at the expense of people’s livelihoods, therefore turning the affected communities against conservation. Another response has been the ratification of biodiversity-related multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs) such as the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), Ramsar and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). However, for many of these reporting and implementation remains weak. For example, until the year 2000, performance on CITES reporting requirements was mixed.

However, most biodiversity occurs outside of protected areas, and if it is to be effectively conserved then alternative measures need to be adopted. The integration of conservation measures into other landuse systems is essential, and ensuring a fair and equitable sharing of the benefits from biodiversity use is a fundamental component of this. Experience throughout the region has demonstrated the value of community involvement in biodiversity conservation and ensuring its sustainable use.

Although some countries have incorporated the MEAs into national policies and framework laws, few have succeeded in achieving the enforcement of policies and laws. Similarly, while 37 countries in Africa have ratified the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety, less than ten have put in place mechanisms, including the legal and institutional frameworks, to operationalize it. The implementation of the national biodiversity strategies and action plans (BSAP) by a number of African countries has yet to generate the expected impacts in terms of conservation, sustainable use and equitable sharing of benefits accruing from commercial transactions on biodiversity.

Outlook

Biodiversity will continue to be the most important resource endowment for many countries in the region, sustaining both national economies and community livelihoods. As the population grows, demands on the resource to meet basic needs will intensify. Expanding economic activities and human settlements will encroach on important habitats thus compromising the survival of many species. Reduced access to the resources for medicine and food will adversely affect the livelihoods of many communities. With increasing scarcity, more and more biodiversity resources, including wildlife, woodlands, medicinal plants, etc. will be managed for commercial purposes to the exclusion of the poor. This too will impact on livelihoods and overall levels of well-being. Most biodiversity will continue to be located outside protected areas. With the continued realization of the importance of biodiversity resources in national development, efforts will be pursued to safeguard the resource. Financial commitments and support will be required to finalize these frameworks and start the implementation.

Action

Africa’s commitment and goodwill on biodiversity conservation have been reasserted in the Environment Initiative of NEPAD. The 2010 targets adopted by the CBD and reiterated at the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD), Johannesburg, South Africa in 2005 are important global targets that Africa has also committed to. The priorities for biodiversity include:

- Supporting and improving implementation of the objectives of the CBD, in particular the sustainable use and fair and equitable sharing of benefits and the development of an ecosystem approach to sustainable management.

- Bringing communities and other resource users on board as both managers and planners. This could include support for and the development of community conservation areas based on multiple land uses and the objectives of the CBD.

- Implementation of the African Protected Areas Initiative (APAI).

- Supporting and implementing the CBD’s Bonn Guidelines on Access to Plant Genetic Resources and Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization.

- Preventing and controlling invasive alien species,through control of entry points, awareness raising,aquatic and terrestrial programmes, and developing a special programme on control of invasive alien species on Africa’s SIDS.

- Adopting or strengthening measures in line with the CBD 2010 targets to promote the conservation of ecosystems, as well as species and genetic diversity. Such measures may include better integration ofland use, development, and conservation by recognizing that most species will occur outside protected areas.

The following actions can be implemented by governments in the short to medium term:

- Strengthening national conservation programmes through increased financing and introducing innovative means of generating revenues from biodiversity assets. This revenue can provide additional funding for conservation programmes, some of which can be targeted at enhancing support to planning, research, monitoring and public awareness.

- Instituting and/or strengthening a system of transfers of benefit accruing from biological resources to communities through collaborative management of ecosystems.

Stakeholders

Partnerships with other stakeholders are essential to implementing the recommended actions. These partnerships in the first instance should be with resource users and managers, such as local communities and other landholders. For some areas partnerships with the private sector, civil society organizations, farmers, the scientific and research community, and the donor community will be important.

Result and target date

The actions can be implemented in the short to medium term (five to ten years). However this is an area that will require ongoing attention.

Further reading

- CBD, 2006. Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety (Montreal, 29 January 2000) – Status of Ratification and Entry into Force.

- CI, 2006a. Biodiversity Hotspots. Conservation International Washington D.C.

- CI, 2006b. Eastern Afromontane. Conservation International, Washington D.C.

- Davis, S.D., Heywood,V.H. and Hamilton,A.C. (eds. 1994). Centres of plant diversity. A guide and strategy for their conservation.Vol. 1: Europe, Africa and the Middle East. IUCN Publications Unit, Cambridge.

- Groombridge, B. and Jenkins, M., 2002. World Atlas of Biodiversity: Earth's Living Resources in the 21st Century. University of California Press, Berkeley

- Kingdom of Swaziland, 2003. National Drylands Development Programme, 2003.

- Secretariat of the CBD, UNEP and UN, 2001. Global Biodiversity Outlook. Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, United Nation Environment Programme, and United Nations. Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Montreal.

- UNEP, 2006. Africa Environment Outlook 2. Nairobi, Kenya.

- UNEP, 2002. Outreach Material for the WSSD. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi.

- WEHAB Working Group, 2002. A Framework for Action on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Management. Proceedings of the World Summit on Sustainable Development, Johannesburg, South Africa, 26 August – 4 September.

- WRI,UNDP, UNEP and World Bank, 2000.World Resources 2000-2001: People and Ecosystems - the Fraying Web of Life.World Resources Institute, Washington, D.C.

|

|

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |