A framework for analyzing vulnerability of the Arctic to climate change

This is Section 17.2.1 of the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment. Lead Authors: James J. McCarthy, Marybeth Long Martello; Contributing Authors: Robert Corell, Noelle Eckley Selin, Shari Fox, Grete Hovelsrud-Broda, Svein Disch Mathiesen, Colin Polsky, Henrik Selin, Nicholas J.C.Tyler; Corresponding Authors: Kirsti Strøm Bull, Inger Maria Gaup Eira, Nils Isak Eira, Siri Eriksen, Inger Hanssen-Bauer, Johan Klemet Kalstad, Christian Nellemann, Nils Oskal, Erik S. Reinert, Douglas Siegel-Causey, Paal Vegar Storeheier, Johan Mathis Turi

Building on this history, the combined effects of climate and other stressors can be examined via the following questions:

- How do social and biophysical conditions of human–environment systems in the Arctic influence the resilience of these systems when they are impacted by climate and other stressors?

- How can the coupled condition of these systems be suitably characterized for analysis within a vulnerability framework?

- To what stresses and combinations of stresses are coupled human–environment systems in the Arctic most vulnerable?

- To what degree can mitigation and enhanced adaptation at local, regional, national, and global scales reduce vulnerabilities in these systems?

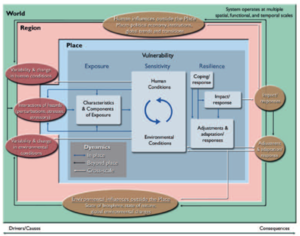

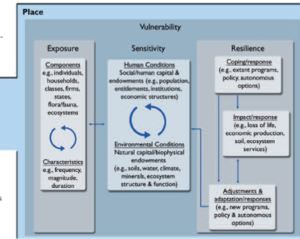

Answers to these questions require a holistic research approach that addresses the interconnected and multiscale character of natural and social systems. A framework for this approach (Fig. 17.1) depicts a cross-scale, coupled human–environment system.The multiple and linked scales in each diagram are reflected in the nesting of different colors with blue (place), pink (region), and green (world).The place (whatever its spatial dimensions) contains the coupled human–environment system whose vulnerability is being investigated. Figure 17.2 presents a more detailed schematic of the place.The influences (including stresses) acting on the place arise from outside and inside its borders. However, given the complexity and possible non-linearity of these influences, their precise character (e.g., kind, magnitude, and sequence) is commonly specific to the place-based system. This system has certain attributes denoted as human and environmental conditions.These conditions can interact with one another and can enable or inhibit certain responses in, for example, the form of coping, adaptation, and impacts. Negative impacts at various scales result when stresses or perturbations exceed the ability of the place-based human– environment system to cope or respond.There are a number of feedbacks and interactions within and around the place-based system and these dynamics can extend across placebased, regional, and global levels. Impacts and mitigating and adaptive responses, for example, can modify societal conditions of the place and/or alter societal and environmental influences within the place and at regional and global scales.

The vulnerability of the coupled human–environment system can be thought of as the potential for this system to experience adverse impacts, taking into consideration the system’s resilience.Adverse impacts might arise from phenomena such as climate change, pollution, and social change. The system’s resilience depends on its ability to counter sources of adverse change and to adapt to and otherwise cope with their consequences. It is important to note differences between mitigation and adaptation. Mitigation involves the amelioration of a stress at its source (e.g., changes in fossil fuel consumption resulting in reduced [[gas[greenhouse gas]]] (GHG) emissions).While the Arctic is experiencing the effects of climate change, actions to mitigate climate change through GHG reductions are largely dependent on the actions of people living at more southern latitudes. Adaptation (e.g., through mobility, new hunting or fishing practices, and/or the development or adoption of new technologies) requires that resources and other forms of capacity be accessible to the human–environment system in question. Such resources and capacity can take years, even generations to develop.

Chapter 17: Climate Change in the Context of Multiple Stressors and Resilience

17.1. Introduction (A framework for analyzing vulnerability of the Arctic to climate change)

17.2. Conceptual approaches to vulnerability assessments

17.2.1. A framework for analyzing vulnerability

17.2.2. Focusing on interactive changes and stresses in the Arctic

17.2.3. Identifying coping and adaptation strategies

17.3. Methods and models for vulnerability analysis

17.4. Understanding and assessing vulnerabilities through case studies

17.4.1. Candidate vulnerability case studies

17.4.2. A more advanced vulnerability case study

17.5. Insights gained and implications for future vulnerability assessments

References

Citation

Committee, I. (2012). A framework for analyzing vulnerability of the Arctic to climate change. Retrieved from http://editors.eol.org/eoearth/wiki/A_framework_for_analyzing_vulnerability_of_the_Arctic_to_climate_change- ↑ Turner, B.L., II, R.E. Kasperson, P. Matson, J.J. McCarthy, R.W. Corell, L. Christensen, N. Eckley, J.X. Kasperson, A. Luers, M.L. Martello, C. Polsky, A. Pulsipher and A. Schiller, 2003a. A Framework for Vulnerability Analysis in Sustainability Science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100:8074–8079.

- ↑ Ibid.