Sunspots: Increasing the Solar Energy that Reaches Earth

Periodic changes in the alignment between the sun’s rotational axis and the gravitational center of the solar system produces intense fluctuations in vertical magnetic fields of the sun. These divert heat flow from deeper layers in the sun and generate patches of fluctuating temperatures on the surface that manifest as sunspots. Although Chinese astronomers recorded the presence of sunspots as early as 28 BC, systematic counts of sunspots began with the invention of the optical telescope. These telescopes show that the number of sunspots varies with about an 11-year period as well as with some less-predictable longer cycles.

A drawing of a sunspot in the chronicle of the 12th-century English monk John of Worcester.

One might presume that solar energy reaching Earth would decline during times of high sunspot activity, but the opposite is true. Heightened solar magnetic field activity that produces sunspots increases the overall brightness of the sun and more than compensates for the dark areas within the sunspots. Measurements from spacecraft since 1978 affirm that total solar energy oscillates 0.05% to 0.07% in synchrony with sunspot number. Variations in solar energy of this magnitude should account for only about a 0.03°C change in global temperatures. By contrast, solar energy reaching Earth varies 6.5% between the perihelion and aphelion, 28% between seasons in the tropics, and 4.5% during the 41,000-year cycle of obliquity. Differences from other external factors should thus dwarf the 0.05% to 0.07% oscillations resulting from sunspots. Nonetheless, sunspot number and mean surface temperatures of the terrestrial Northern Hemisphere are positively correlated. [1] For example, the period from 1645 to 1715—the middle of the Little Ice Age when Europe, North America, and perhaps much of the world suffered bitterly cold winters—was largely devoid of sunspots. One possible explanation is that during periods of low solar magnetic fluxes (i.e., few sunspots), up to 18% more cosmic rays penetrate the solar system and strike Earth. [2] Cosmic rays, as they pass through Earth’s atmosphere, may leave a trail of ions (charged atoms) that could serve as condensation centers on which cloud droplets form. Therefore, cosmic rays might stimulate the formation of clouds that reflect solar energy and cool the planet. Recent studies, however, have found little correlation between cosmic rays and cloud formation. [3]

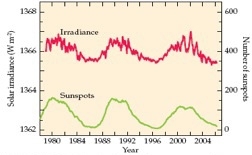

Solar irradiance (energy per unit area) and sunspots. Total solar irradiance since 1979, as measured by radiometers on several spacecraft; shown are 81-day (red) running averages. Number of sunspots at the Zurich Obsersatory; yearly (green) running averages. (After Foukal et al. 2006; SIDC, RWC Belgium, World Data Center for the Sunspot Index, Royal Observatory of Belgium.)

Solar irradiance (energy per unit area) and sunspots. Total solar irradiance since 1979, as measured by radiometers on several spacecraft; shown are 81-day (red) running averages. Number of sunspots at the Zurich Obsersatory; yearly (green) running averages. (After Foukal et al. 2006; SIDC, RWC Belgium, World Data Center for the Sunspot Index, Royal Observatory of Belgium.)

Do sunspots significantly affect Earth’s climate, and might they be responsible for some of the recent climate anomalies? [4] The current consensus is that the influence of sunspots, which is an external forcing factor, is smaller than the influence of internal forcing factors such as Earth’s atmospheric composition. [5]

[1] Usoskin, I. G., M. Schussler, S. K. Solanki, and K. Mursula (2005) Solar activity, cosmic rays, and Earth's temperature: A millennium-scale comparison. Journal of Geophysical Research-Space Physics 110: doi:A10102.

[2] -do-

[3] Kristjánsson, J. E., C. W. Stjern, F. Stordal, A. M. Fjæraa, G. Myhre, and K. Jónasson (2008) Cosmic rays, cloud condensation nuclei and clouds – a reassessment using MODIS data. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 8:7373-7387.

[4] Kanipe, J. (2006) A cosmic connection. Nature 443:141-143

[5] Foukal, P., C. Frohlich, H. Spruit, and T. M. L. Wigley (2006) Variations in solar luminosity and their effect on the Earth's climate. Nature 443:161-166.

This is an excerpt from the book Global Climate Change: Convergence of Disciplines by Dr. Arnold J. Bloom and taken from UCVerse of the University of California.

©2010 Sinauer Associates and UC Regents