Improving freshwater management in Africa

Contents

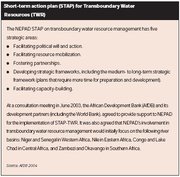

- 1 Introduction Fika Phatso Dam in the eastern Free State, South Africa. In recent years there has been a dramatic fall in water levels due to, among other factors, overutilization. (Source: A. Mohamed) An improved legal and institutional context with enhanced transparency and accountability could contribute to more effective resource management, and at the same time maximize available opportunities and ensure the fair and equitable distribution of benefits. This would have positive spinoffs at multiple levels, including for human well-being and in particular health and nutrition, livelihoods and economic development. An improved governance framework will need to address: Basic principles, such as equity and efficiency in water allocation and distribution, the need for integrated management approaches using the catchment and basin as basic units, and the need to balance the different water uses (eg for socioeconomic development versus maintenance of ecosystem integrity);The roles of government, civil society and the private sector and their responsibilities regarding management and administration of water resources (Improving freshwater management in Africa) ; * Regulatory regimes (eg water tariffs and subsidies to resource users and polluters) and; * Risk management of water-related disasters, and climate variability and change. Short-term action plan (STAP) for Transboundary Water Resources (TWR) (Source: AfDB 2004)

- 2 Mainstreaming gender

- 3 Finances

- 4 Further reading

An increasing number of countries are developing new policies, strategies and laws for water resource development and management based on the principles of integrated water resources management (IWRM) that aim at decentralization, integration and cost-recovery. The Global Water Programme (GWP), for example, seeks to encourage dialogue among financiers, water professionals, decision-makers and water users at regional and country level. For example, in Ethiopia a process has been initiated to develop an IWRM plan to be implemented in connection with the process of decentralization in the country, and to this end has developed various laws, policies and strategies. Countries which are undergoing watersector reform have often restructured their institutional and legal frameworks. This may include setting up river and lake catchment and basin organizations.

The multiplicity of transboundary water basins in Africa has led to international cooperation and action plans, such as the establishment of the Africa Ministerial Council on Water (AMCOW) and the Africa Water Task Force to steer the processes. Through the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD), a short-term action plan (STAP) was prepared, with the aim of strengthening the enabling environment for effective cooperative management and development of transboundary water resources, and of initiating the implementation of prioritized programmes. Also, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) Protocol on Shared Watercourses, and the Nile Basin Initiative (NBI) are examples of transboundary cooperation that unlock development potentials and seek win-win benefits. Though it is necessary to manage water resources at national and sub-regional levels, the management of water resources is best done at local level. Community-based natural resource management — especially water management — plays a critical part within holistic and integrated approaches for solving water scarcity problems. Key components of successful local water management are decentralizing decision making, accountability, and fostering ownership.

Capacity-building needs to be systematically included in IWRM plans. The capacity should be developed at all levels. Tailor-made capacity-building programmes for Africa can be developed and sustained that include institutional, human (technical and managerial), material and technological as well as financial aspects. Creative approaches (these are described more fully in Box 4) can be applied, in particular:

- Networking of education and training institutions, nationally and internationally (eg Capacity Building for Integrated Water Resources Management (Cap-Net and GWP);

- Establishing and sustaining national and international centres of excellence for critical issues;

- Enhancing distance education (eg the United Nations University (UNU) Water Virtual Learning Centre); and

- Strengthening partnerships with international training institutions (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) Institute for Water Education (UNESCO-IHE).

Opportunities can be increased through establishing partnerships between the public sector and civil society and the private sector. This may improve the implementation of community projects, particularly targeting the poor (see for example, Box 14: Private Sector Participation in the Zambian water supply and sanitation sector).

Political will and a strategic approach to address this issue of capacity strengthening and retention, are essential. At the Pan-African Conference on Implementation and Partnership on Water, African water ministers recognized that one of the biggest challenges that must be addressed immediately to reach the African Water Vision and the Millen(MDGs) is human and institutional capacity-building.

For establishing adequate monitoring and assessment programmes that can answer today’s questions and prepare for tomorrow, new and emerging monitoring technologies (eg the European Space Agency (ESA) and the UNESCO Earth Observation for Integrated Water Resources Management in Africa (TIGER-SHIP)) exist that can be exploited (PANAFCON 2003 recommendations). Institutions have been established (eg International Institutions for Geo-Information Science and Earth Observations (ITC)) that can underpin such advances and can provide on-the-ground monitoring, assessment and associated capacity development.

Mainstreaming gender

Central to integrated water management at basin level are the interests of the people who carry buckets of water to their homes or fields to ensure a minimum level of welfare. Women are usually the ones who are most directly concerned with the family’s water supply. Women also play a pivotal role in agriculture by providing labour to family fields or their own fields. Although the pivotal role of African women in the provision and safeguarding of water for domestic and agricultural use is widely recognized, they have a much less influential role in the management and decisionmaking processes related to water resources than men.

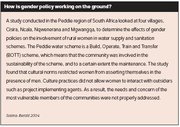

Sustainable water resources management requires that the role of women is reflected in institutional arrangements, and that men and women alike are given influential roles at all levels in water resources programmes, including in decision making and implementation. Mainstreaming gender concerns along these lines can speed up the achievement of sustainable water management by improving the access of women and men to water and water-related services to meet their essential needs. Nevertheless, in realizing the active and effective participation of women in IWRM, consideration has to be given to the way in which societies assign certain social, economic and cultural roles to men and women. These social and cultural differences require tailor-made approaches, mechanisms and activities for women to participate in IWRM.

Finances

The World Panel on Financing Water Infrastructure proposed several measures for solving the problem of financing water projects in developing countries. One such measure was to urge donors (multilateral financial institutions like the World Bank Group, the regional development banks and the European Investment Bank (EIB)) to honour their commitments to increase aid to the water sector. Others included the encouragement of international commercial lending, the promotion of private investment and operations, and the recognition and support of community initiatives and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) by providing them with the resources necessary to perform their important role.

In the light of the MDGs, urgent water needs of poor households take centre stage. The Water and Sanitation Program (WSP) acknowledges the important role played by small water supply and sanitation providers, such as CBOs and the private sector. However, these providers are faced with problems related to finance and access to credit facilities. Microfinance is proposed as an option to financing small water and sanitation services in Sub-Sahara Africa (SSA). Opportunities exist for microfinance in Africa due to two main factors: the market size is quite significant and market penetration to date has been very low due to inappropriate financing products. It has been estimated that there are over 1,000 providers or initiatives in SSA, of which perhaps only 20 are on their way to sustainability, while market penetration is only 7 percent of all poor households in Western Africa and even lower in Eastern and Southern Africa.

Many countries have embarked on cost-recovery approaches in providing water to urban and rural areas at various degrees of recovery rates. In most cases, operations and maintenance (O&M) charges are being covered in cost-recovery schemes. In Madagascar for instance, cost-recovery of O&M for irrigation amounts to 75 percent.

Available evidence indicates that only a few countries attempt to recover capital costs from users. One major problem facing water authorities is the poor water revenue and the use of flat-rate charging of water services which is not feasible from either an environmental or financial viewpoint. It does not penalize irrational consumption nor reward rational use of water resources. Furthermore, cost-recovery requires proper functioning meters and monitoring real consumption, in addition to realistic pricing for water production and delivery, and for collecting and treating wastewater. Water management agencies should consider the opportunities for privatizing certain services, such as water treatment. Water meters should be promoted to encourage efficient use of the scarce resource and to reduce wastage.

New financial mechanisms can be developed and delivery systems improved to reach greater numbers of clients. There is a need to find non-conventional financial and economic instruments. Through market research, financial services can be further strengthened.

Further reading

- AMCOW, 2003. Ministerial Communiqué on the Pan African Implementation and Partnership Conference on Water, 12 December 2003, in Addis Ababa.

- Cap-Net, 2002. Capacity Building for Integrated Water Resources Management: The importance of Local Ownership, Partnerships and Demand Responsiveness.

- Dinar,A. and Subramanian, A., 1997. Water Pricing Experiences: An International Perspective. World Bank Technical Paper No. 386.

- GWP, 2006. Eastern Africa Regional Profile. Global Water Partnership.

- Mehta, M. and Virjee, K., 2003. Financing Small Water-supply and Sanitation Service Providers: Exploring the Micro finance Option in sub-Saharan Africa. Water and Sanitation Programme, Nairobi.

- PANAFCON, 2003. Outcomes and Recommendations of the Pan-African Implementation and Partnership Conference on Water (PANAFCON), Addis Ababa, December 8-13, 2003.

- UNEP, 2006. Africa Environment Outlook 2

- WWC, 2003. Financing Water for All. Report of the World Panel on Financing Water Infrastructure. World Water Council, 3rd World Water Forum and the Global Water Partnership.

|

|

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |