Purple loosestrife (Agricultural & Resource Economics)

Contents

Purple loosestrife

Purple loosestrife is an erect perennial herb that grows up to 2.5 m tall, develops a strong taproot, and may have up to 50 stems arising from its base. Also known as spiked lythrum, salicaire, rainbow weed, and bouquet violet, purple loosestrife (scientific name:Lythrum salicaria L.) is one of 13 species of plant in the genus Lythrum in the family of Loosestrife (Lythraceae).

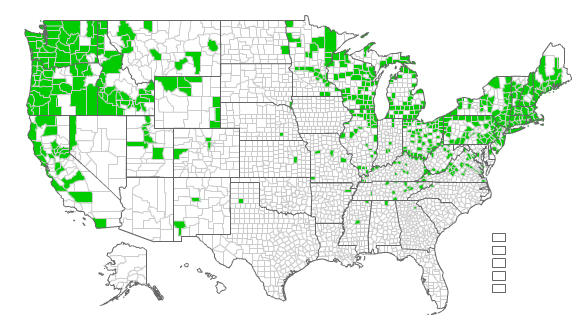

Its native range is thought to extend from Great Britain to central Russia from near the 65th parallel to North Africa. It also occurs in Japan, Korea, and the northern Himalayan region. The species has been introduced to Australia, Tasmania, and New Zealand. Since its introduction to North America, this alien plant (Invasive species) has spread rapidly into Canada, and throughout most of the United States where, according to the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, purple loosestrife now occurs in every state except Florida. This plant has become a major problem in Wisconsin and some of the northeastern states. Several factors have contributed to the spread of purple loosestrife such as its potential for rapid growth, its enormous reproductive capacity, lack of natural diseases or predators, its use as an ornamental, and for bee forage.

|

Conservation Status |

|

Scientific Classification Kingdom: Plantae |

Description

Purple loosestrife is an erect perennial herb that grows up to 2.5 m tall, develops a strong taproot, and may have up to 50 stems arising from its base. Its 50 stems are four-angled and glabrous to pubescent. Its leaves are sessile, opposite or whorled, lanceolate (2-10 cm long and 5-15 mm wide), with rounded to cordate bases. Leaf margins are entire. Leaf surfaces are pubescent.

Each inflorescence is spike-like (1-4 dm long), and each plant may have numerous inflorescences. The calyx and corolla are fused to form a floral tube (also called a hypanthium) that is cylindrical (4-6 mm long), greenish, and 8-12 nerved. Typically the calyx lobes are narrow and thread-like, six in number, and less than half the length of the petals. The showy corolla (up to 2 cm across) is rose-purple and consists of five to seven petals. Twelve stamens are typical for each flower. Individual plants may have flowers of three different types classified according to stylar length as short, medium, and long. The short-styled type has long and medium length stamens, the medium type has long and short stamens, and the long-styled has medium to short stamens. The fruit is a capsule about 2 mm in diameter and 3-4 mm long with many small, ovoid dust-like seeds (< 1 mm long).

Other species of Lythrum that grow in the United States have 1-2 flowers in each leaf-like inflorescence bract and eight or fewer stamens compared to L. salicaria, which has more than two flowers per bract and typically twelve stamens per flower. Lythrum virgatum, another species introduced from Europe closely resembles L. salicaria, but differs in being glabrous (lacking plant hairs), and having narrow leaf bases. The latter two species interbreed freely producing fertile offspring, and some taxonomists consider them to be a single species.

Distribution

Eurasia; throughout Great Britain, and across central and southern Europe to central Russia, Japan, Manchuria China, southeast Asia and northern India. Within the United States, purple loosestrife now occurs according to the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, in every state except Florida.

Habitat

Habitats include fens, marshes, borders of ponds and rivers, and ditches. This is species is still grown in flower gardens, using hybrids that are supposedly sterile. However, research has revealed that many of these hybrids can form viable seeds when wild forms of Purple Loosestrife are present in a given locality as a result of cross-pollination between these two groups of plants. Purple Loosestrife often escapes from cultivation and invades wetlands, sometimes forming dense stands that exclude other plants. This plant has become a major problem in Wisconsin and some of the northeastern states.

Faunal Associations

The flowers attract long-tongued bees and butterflies, including Bombus spp. (Bumblebees) and the butterfly Pieris rapae (Cabbage White). The seeds are too small to be of any interest to birds, and it is unclear to what extent mammalian herbivores feed on the foliage. There have been attempts recently to release leaf beetles from Europe as a biocontrol measure. This species probably provides cover to some wetland species of birds because of its tall dense vegetation.

Ethnobotanic

It was introduced to North America in the early 1800's where it first appeared in ballast heaps of eastern harbors. Most likely seeds were transported as contaminants in the ballast or possibly attached to raw wool or sheep imported from Europe. It was additionally brought to the northeastern U.S. and Canada in the 1800s, for ornamental and medicinal uses. It is still widely sold as an ornamental, except in states such as Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Illinois where regulations now prohibit its sale, purchase and distribution. Immigrants might have deliberately introduced L. salicaria for its value as a medicinal herb in treating diarrhea, dysentery, bleeding wounds, ulcers, and sores, for ornamental purposes, or as a source of nectar and pollen for beekeepers. In states where it is permitted, purple loosestrife continues to be promoted by horticulturists for its beauty as a landscape plant and for bee-forage. Purple loosestrife has been of interest to beekeepers because of its nectar and pollen production. However, honey produced from it is apparently of marginal quality.

Horticultural

Horticultural cultivars of purple loosestrife (Lythrum spp.) were developed in the mid-1900s for use as ornamentals. Initially, these were thought to be sterile, and therefore safe for horticultural use. Recently, under greenhouse conditions, experimental crosses between several cultivars and wild purple loosestrife and the native L. alatum produced hybrids that were highly fertile. Comparable, subsequent experiments performed under field conditions produced similar results, suggesting that cultivars of purple loosestrife can contribute viable seeds and pollen that can contribute to the spread of purple loosestrife indicate that such results suggest the need to prohibit cultivars of this species.

Noxiousness

Purple loosestrife grows most abundantly in parts of Canada, the northeastern United States, the Midwest, and in scattered locations in the West. Although this species tolerates a wide variety of soil conditions, its typical habitat includes cattail marshes, sedge meadows, and bogs. It also occurs along ditch, stream, and riverbanks, lake shores, and other wet areas. In such habitats, purple loosestrife forms dense, monospecific stands that can grow to thousands of acres in size, displacing native, sometimes rare, plant species and eliminating open water habitat. The loss of native species and habitat diversity is a significant threat to wildlife, including birds, amphibians, and butterflies, that depend on wetlands for food and shelter. Purple loosestrife monocultures also cause agricultural loss of wetland pastures and hay meadows by replacing more palatable native grasses and sedges.

Having a noxious weed designation in some states prohibit its importation and distribution, but it is readily available commercially in many parts of the country. Lythrum salicaria has been labeled the “purple plague." because of its epidemic devastation to natural communities. The species is included on the Nature Conservancy’s list of “America’s Least Wanted -The Dirty Dozen”.

Impact/Vectors

Naturalized purple loosestrife was relatively obscure from the time of its introduction into North America in the early 1800s until 1930, when a significant increase in populations invading wetlands and pastures was documented. Reasons for the apparent sudden colonization and spread of this species include the disturbance of natural systems by human activities including agricultural settlement, construction of transport routes such as canals, highways, and perhaps, nutrient increases to inland waters. Absence of natural enemies and ornamental use are other possible causes for purple loosestrife’s rapid expansion in North America. Recently created irrigation systems in many western states have supported further establishment and spread of L. salicaria.

The acquisition of adaptive characteristics from native species of Lythrum may have enhanced purple loosestrife’s invasive success. It will hybridize with Lythrum alatum, a widespread, native North American species, in natural settings. Under certain circumstances fertile hybrids are produced that can cross with weedy purple loosestrife. Such interspecific hybrids could serve as a “hybrid bridge” for the transfer of adaptive traits from native L. alatum into weedy populations of purple loosestrife.

North American naturalized populations of purple loosestrife often form monospecific stands, whereas, in its native Eurasian habitat the species comprises 1-4% of the vegetative cover. Purple loosestrife causes annual wetland losses of about 190,000 hectares in the United States. The species is most abundant in the Midwest and Northeast where it infests about 8,100 hectares in Minnesota, 12,000 ha in Wisconsin, over 12,000 ha in Ohio, and a larger area in New York State. Recent distributional surveys document the occurrence of monocultures in every county in Connecticut, where it has been found in 163 wetland locations. At the Effigy Mounds National Monument (EFMO), combined populations of purple loosestrife cover an area of 5 to 10 hectares growing in regularly disturbed sites. This species has a major visual impact on the vegetation of EFMO, and it has the potential to invade and replace native communities endangering the areas' primary resources.. In response to the alarming spread of this exotic species, at least 13 states (e.g., Minnesota, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Washington, and Wisconsin) have passed legislation restricting or prohibiting its importation and distribution.

Numerous studies demonstrate the aggressive and competitive nature of purple loosestrife. Fernald (see Further Reading section for this and other authors mentioned) reported a loss of native plant diversity in the St. Lawrence River floodplain following the invasion of purple loosestrife and another exotic, Butomus umbellatus L. Gaudet and Keddy report declining growth for 44 native wetland species after the establishment of Lythrum. Among the species tested, Keddy found that purple loosestrife was the most competitive. His hierarchical rank, arranged from most to least competitive, illustrates the dominance of this invasive weed over many common natives. In the Hamilton Marshes adjacent to the Delaware River, annual above-ground production of L. salicaria far exceeded all other plant species’ production combined.

Purple loosestrife provides little food, poor cover, and few nesting materials for wildlife. Waterfowl nesting becomes more difficult as clumps of L. salicaria restrict access to open water and offer concealing passageways for predators such as foxes and raccoons. Non-game species, including black terns and marsh wrens, also lose nesting sites when purple loosestrife infests their normal habitats. Balogh and Bookhout report that dense stands of purple loosestrife provide poor waterfowl and muskrat habitat. Red-wing blackbirds appear to be the only species to cope with changes in wetlands caused by purple loosestrife. In many areas where L. salicaria populations have increased, wildlife species have declined. While some studies may fail to demonstrate cause and affect relationship, they firmly establish circumstantial evidence implicating that Lythrum’s invasion is responsible for major changes in wetland communities.

Purple loosestrife prefers moist, highly organic soils but can tolerate a wide range of conditions. It grows on calcareous to acidic soils, can withstand shallow flooding, and tolerates up to 50% shade. Purple loosestrife has low nutrient requirements and can withstand nutrient poor sites. Under experimental, nutrient-deficient conditions, the root/shoot ratio increased and provided purple loosestrife with a competitive advantage over the native species Epilobium hirsutum. Survival and growth of L. salicaria was greatly improved by fertilizer treatment and greater spacing between plants. Such results suggest that excessive use of fertilizers and the release of phosphates, nitrates, and ammonia into the environment has enhanced the success of Lythrum .

Purple loosestrife flowers from July until September or October. Flowering occurs 8-10 weeks after initial spring growth. The lowermost flowers of the inflorescence open first and flowering progresses upward. The capsules mature in the same sequence and the lowermost will ripen and disperse its seeds while flowering is still occurring further up the inflorescence. Thompson et al. estimated that on average, a mature plant produces about 2,700,000 seeds annually. Purple loosestrife seeds are mostly dispersed by water, but wind and mud adhering to wildlife, livestock, vehicle tires, boats, and people serve also as agent. Seeds are relatively long-lived, retaining 80% viability after 2-3 years of submergence. Welling & Becker investigated seed bank dynamics in three wetland sites in Minnesota and noted a mean density of 410,000 seeds per square meter in the top 5 cm of soil, which was more than all other species combined.

Spring-germinated seedlings have a higher survival rate than summer-germinated seedlings. Seedlings that germinate in the spring will flower the first year, whereas, summer-germinated seedlings develop only five or six pairs of leaves before the end of the growing season. Since its seeds are small, weighing about 0.06 mg each and carry little food reserves, germination must occur under conditions where photosynthesis can occur immediately. A strong taproot develops quickly in seedlings and persists throughout the life of the plant. The aerial shoots die in the fall and new shoots arise the following spring from buds on the rootstocks. Shoots destroyed by fire, herbicides (Pesticide), or mechanical removal can also regenerate from the rootstock. As plants mature, they produce more and more aerial shoots forming very dense clumps of growth. Purple loosestrife can spread vegetatively by resprouting from stem cuttings and from regeneration of pieces of root stock. Rhizomatous growth is insignificant in purple loosestrife.

Biology and Spread

Purple loosestrife enjoys an extended flowering season, generally from June to September, which allows it to produce vast quantities of seed. The flowers require pollination by insects, for which it supplies an abundant source of nectar. A mature plant may have as many as thirty flowering stems capable of producing an estimated two to three million, minute seeds per year.

Purple loosestrife also readily reproduces vegetatively through underground stems at a rate of about one foot per year. Many new stems may emerge vegetatively from a single rootstock of the previous year. "Guaranteed sterile" cultivars of purple loosestrife are actually highly fertile and able to cross freely with purple loosestrife and with other native Lythrum species. Therefore, outside of its native range, purple loosestrife of any form should be avoided.

Management Options

Small infestations of young purple loosestrife plants may be pulled by hand, preferably before seed set. For older plants, spot treating with a glyphosate type herbicide (e.g., Rodeo® for wetlands, Roundup® for uplands) is recommended. These herbicides may be most effective when applied late in the season when plant are preparing for dormancy. However, it may be best to do a mid-summer and a late season treatment, to reduce the amount of seed produced.

While herbicides and hand removal may be useful for controlling individual plants or small populations, biological control is seen as the most likely candidate for effective long term control of large infestations of purple loosestrife. As of 1997, three insect species from Europe have been approved by the U.S. Department of Agriculture for use as biological control agents. These plant-eating insects include a root-mining weevil (Hylobius transversovittatus), and two leaf-feeding beetles (Galerucella calmariensis and Galerucella pusilla). Two flower-feeding beetles (Nanophyes) that feed on various parts of purple loosestrife plants are still under investigation. Galerucella and Hylobius have been released experimentally in natural areas in 16 northern states, from Oregon to New York. Although these beetles have been observed occasionally feeding on native plant species, their potential impact to non-target species is considered to be low.

Further Reading

- Lythrum salicaria L., Encyclopedia of Life, (accessed October 9, 2009)

- Lythrum salicaria L., Ling Cao. 2009, USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database, Gainesville, FL., Revision Date: 8/5/2009

- PLANTS profile for Lythrum salicaria L., prepared by Urbatsch, Department of Plant Biology, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, Louisiana National Plant Data Center, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Natural Resources Conservation Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture

- Purple Loosestrife Information Center

- Invasive Plant Atlas of the United States

- Cornell University Non-indigenous Plant Species Program

- Biological Control of Purple Loosestrife Program Illinois Natural History Survey

- Flora of Pakistan @ eFloras.org

- Flora of China @ eFloras.org

- Illinois Wildflowers by Dr. John Hilty

- Purple Loosestrife, National Park Service, (accessed October 9, 2009)

- USDA NRCS National Plant Data Center & Louisiana State University-Plant Biology. http://plants.usda.gov/plantguide/doc/pg_lysa2.doc

- U.S. EPA (Environmental Protection Agency). (2008) Predicting future introductions of nonindigenous species to the Great Lakes. National Center for Environmental Assessment, Washington, DC; EPA/600/R-08/066F. Available from the National Technical Information Service, Springfield, VA, and http://www.epa.gov/ncea.

- USDA, NRCS 2000. Wetland flora CD-ROM. <http://www.pwrc.usgs.gov/wli/wetprods.htm>. Wetland Science Institute, Laurel, Maryland.

- Anderson, N.O. & P.D. Ascher 1993. Male and female fertility of loosestrife (Lythrum) cultivars. Journal of the American Horticulture Society 118(6):851-858

- Balogh, G.R. & T.A. Bookhout 1989a. Purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) in Ohio's Lake Erie marshes. Ohio Journal of Science 89(3):62-64. maps.

- Batra, S.W.T., D. Schroeder, P.E. Boldt, & W. Mendel 1986. Insects associated with purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria L.) in Europe. Proc. Entomol. Soc. Wash., 88(4):748-759, Washington, D.C.

- Blossey, B. 1993. Herbivory below ground and biological weed control: life history of a root-boring weevil on purple loosestrife. Oecologia 94(3):380-387.

- Blossey, B. 1995. A comparison of various approaches for evaluating potential biological control agents using insects on Lythrum salicaria. Biological Control 5(2):113-122.

- Blossey, B. & R.U. Ehlers 1991. Entomopathogenic nematodes (Heterorhabditis spp. and Steinernema anomali) as potential antagonists of the biological weed control agent Hylobius transversovittatus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). J. Invertebrate Pathology 58(3):453-454.

- Blossey, B. & R. Notzold 1995. Evolution of increased competitive ability in invasive nonindigenous plants: a hypothesis. J. Ecology 83(5):887-889.

- Blossey, B. & D. Schroeder 1995. Host specificity of three potential biological weed control agents attacking flowers and seeds of Lythrum salicaria (purple loosestrife). Biological Control 5(1):47-53.

- Blossey, B., D. Schroeder, S.D. Hight, & R.A. Malecki 1994a. Host specificity and environmental impact of two leaf beetles (Galerucella calmariensis and G. pusilla) for biological control of purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria). Weed Science 42(1):134-140.

- Blossey, B., D. Schroeder, S.D. Hight, & R.A. Malecki 1994b. Host specificity and environmental impact of the weevil Hylobius transversovittatus, a biological control agent of purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria). Weed Science 42(1):128-133.

- Brungardt, S. [1992.] Wisdom of a flower ban supported by research. Minn. Sci. Agric. Exp. Stn. Univ. Minn. 47(1):4-5.

- Butterfield, C., J. Stubbendieck, & J. Stumpf 1996. Species abstracts of highly disruptive exotic plants. Version: 16JUL97. Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center Home Page, Jamestown, North Dakota.

- Cole, A.H. 1926. The American manufacture. Vol. 1. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

- Cornell University, Educational Television Center and Media Services 1996. Restoring the balance: biological control of purple loosestrife. Ithaca, New York. 1 videocassette (28 min.)

- Ellis, D. R. 1996. Biological control of purple loosestrife in Connecticut. 1996 Summary Report. <http://www.ceris.purdue.edu/napis/pests/pls/index.html>. (15 May 1997).

- Ellis, D.R. & J.S. Weaver 1996. Purple loosestrife: Survey and biological control. 1995 Summary Report, USDA, APHIS, PPQ, Cooperative Agricultural Pest Survey (CAPS). 9 pp

- Feller Demalsy, M.J. & J. Parent 1989. Analyse pollinique des miels de l’Ontario, Canada. Apidologie 20:127-138

- Fernald, M.L. 1940. The problem of conserving rare native plants. Annual Report, Smithsonian Institution (1939):375-391

- Flack, S. & E. Furlow 1996. America's least wanted "purple plague," "green cancer" and 10 other ruthless environmental thugs. Nature Conservancy Magazine 46(6) November/December. <http://www.tnc.org/news/magazine/nov_dec/index.html>.

- Gabor, T.S., & H.R. Murkin 1990. Effects of clipping purple loosestrife seedlings during a simulated wetland drawdown. Journal of Aquatic Plant Management 28:98-100

- Gardner, S.C. & C.E. Grue 1996. Effects of Rodeo and Garlon 3A on nontarget wetland species in central Washington. Environmental Toxicolog. Chem. 15(4): 441-451.

- Gaudet, C.L. & P.A. Keddy 1988. A comparative approach to predicting competitive ability from plant traits. Nature 334(6179):242-243

- Gaudet, C.L. & P.A. Keddy 1995. Competitive performance and species distribution in shoreline plant communities: a comparative approach. Ecology 76(1):280-291.

- Hayes, B. 1979. Purple loosestrife - The wetlands honey plant. American Bee Journal 119:382-383

- Heidorn, R., & B. Anderson 1991. Vegetation management guideline: purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria L.). Natural Areas Journal 11:172-173.

- Heuch, I. 1979. The effect of partial self-fertilization on type frequencies in heterostylous plants Lythrum salicaria. Annals of Botany 44(5):611-616. ill

- Hight, S.D., B. Blossey, J. Laing & R. DeClerck-Floate 1995. Establishment of insect biological control agents from Europe against Lythrum salicaria in North America. Environmental Entomology 24(4):967-977.

- Jones, M.A. 1976. Destination America. Holt, Rinehart & Winston, New York, New York

- Katovich, E.J.S., R.L. Becker, & B.D. Kinkaid 1996. Influence of nontarget neighbors and spray volume on retention and efficacy of triclopyr in purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria). Weed Science 44(1):143-147.

- Keddy, C. 1988. A review of Lythrum salicaria (purple loosestrife) ecology and management: The urgency for management in Ontario. Natural Heritage League, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. 34 pp

- Keddy, C. 1990. The use of functional as opposed to phylogenetic systematics: a first step in predictive community ecology. IN: S. Kawano, ed. Biological approaches and evolutionary trends in plants. Academic Press, London, U.K.

- Kok, L.T., T.J. McAvoy, R.A. Malecki, S.D. Hight, J.J. Drea, & J.R. Coulson 1992. Host specificity tests of Hylobius transversovittatus Goeze (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), a potential biological control agent of purple loosestrife, Lythrum salicaria L. (Lythraceae). Biological Control 2:1-8.

- Kok, L.T., T.J. McAvoy, R.A. Malecki, S.D. Hight, J.J. Drea, & J.R. Coulson 1992. Host specificity tests of Galerucella calmariensis (L.) and G. pusilla (Duft.) (Coleoptera Chrysomelidae), potential biological control agents of purple loosestrife, Lythrum salicaria L. (Lythraceae). Biological Control 2:282-290.

- LaFleur, A. 1996. Invasive plant information sheet: purple loosestrife. The Nature Conservancy, Connecticut Chapter.

- Lindgren, C.J. & R.T. Clay 1993. Fertility of 'Morden Pink' Lythrum virgatum L. transplanted into wild stands of L. salicaria L. in Manitoba. HortScience 28(9):954.

- Mal, T.K., J. Lovett-Doust, L. Lovett-Doust, & G.A. Mulligan 1992. The biology of Canadian weeds. 100. Lythrum salicaria. Can. J. Plant Sci. Rev. Can. Phytotech. 72(4):1305-1330.

- Mal, T.K., J. Lovett-Doust, & L. Lovett-Doust 1997. Time-dependent competitive displacement of Typha angustifolia by Lythrum salicaria. Oikos 79:26-33.

- Malecki, R.A., B. Blossey, S.D. Hight, D. Schroeder, L.T. Kok, & J.R. Coulson 1993. Biological control of purple loosestrife. BioScience 43:680-686.

- Malecki, R. 1990. Research update-Biological control of purple loosestrife. Report of New York Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York. 4pp + 2 figs

- Malecki, R. 1994. Insect biological weed control: an important and underutilized management tool for maintaining native plant communities threatened by exotic plant introductions. Trans. North. Am. Wildl. Nat. Resoures Conf. (59th) p. 400-404. Wildlife Management Institute, Washington, DC.

- Mann, H. 1991. Purple loosestrife: A botanical dilemma. The Osprey 22:67-77.

- Notestein, A. 1987. Purple loosestrife managed with herbicides at Horicon National Wildlife Refuge (Wisconsin). Restoration and Management Notes 5:91.

- Nyvall, R.F. 1995. Fungi associated with purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) in Minnesota. Mycologia 87(4):501-506.

- Nyvall, R.F. & A. Hu 1997. Laboratory evaluation of indigenous North American fungi for biological control of purple loosestrife. Biological Control 8(1):37-42.

- O'Neil, P. 1992. Variation in male and female reproductive success among floral morphs in the tristylous plant Lythrum salicaria (Lythraceae). American J. of Botany 79(9):1024-1030. Botanical Society of America, Columbus, Ohio

- O'Neil, P. 1997. Natural selection on genetically correlated phenological characters in Lythrum salicaria L. (Lythraceae). Evolution 51(1):267-274.

- Ottenbreit, K.A. 1991. The distribution, reproductive biology, and morphology of Lythrum species, hybrids and cultivars in Manitoba. M.Sc. thesis, Department of Botany, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada.

- Ottenbreit, K.A. & R.J. Staniforth 1994. Crossability of naturalized and cultivated Lythrum taxa. Canadian Journal of Botany 72(3):337-341.

- Pursh, F. 1814. Flora Americae Septentrionalis (or systematic arrangement and description of the plants of North America). White, Cochrane, and Co., London, England.

- Radford, A. E., H. E. Ahles, & C. R. Bell 1968. Manual of the vascular flora of the Carolinas. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. (small line drawing, p. 831).

- Randall, J. M. & J. Marinelli 1996. Invasive plants, weeds of the global garden. Brooklyn Botanic Garden, Handbook #149, Brooklyn, New York. 99 p. (photographs of plants in flower, front cover, p. 5 and p. 81; infested habitat, p. 5).

- Rendall, J. 1989. The Lythrum story: A new chapter. Minnesota Horticulturist 117:22-24.

- Shamsi, S.R.A., & F.H. Whitehead 1974a. Comparative eco-physiology of Epilobium hirsutum L. and Lythrum salicaria L. I. IN General biology, distribution, and germination. Journal of Ecology 62:279-290.

- Shamsi, S.R.A., & F.H. Whitehead 1974b. Comparative eco-physiology of Epilobium hirsutum L. and Lythrum salicaria L. II. IN Growth and development in relation to light. Journal of Ecology 62:631-645.

- Shamsi, S.R.A., & F.H. Whitehead 1977a. Comparative eco-physiology of Epilobium hirsutum L. and Lythrum salicaria L. III. IN Mineral nutrition. Journal of Ecology 65:55-70.

- Shamsi, S.R.A., & F.H. Whitehead 1977b. Comparative eco-physiology of Epilobium hirsutum L. and Lythrum salicaria L. IV. IN Effects of temperature and inter-specific competition and concluding discussion. Journal of Ecology 65:71-84.

- Shamsi, S.R.A. 1976. Effect of a light-break on the growth and development of Epilobium hirsutum and Lythrum salicaria in short photoperiods. Annals of Botany 40(165):153-162.

- Strefeler, M.S., E. Darmo, R.L. Becker, & E.J. Katovich 1996a. Isozyme variation in cultivars of purple loosestrife (Lythrum sp.). HortScience 31(2):279-282.

- Strefeler, M.S., E. Darmo, R.L. Becker, & E.J. Katovich 1996b. Isozyme characterization of genetic diversity in Minnesota populations of purple loosestrife, Lythrum salicaria (Lythraceaae). American Journal of Botany 83(3):265-273.

- Stuckey, R.L. 1980. Distributional history of Lythrum salicaria (purple loosestrife) in North America. Bartonia 17(47):3-20.

- Thompson, D.Q. 1991. History of purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria L.) biological control effects. Natural Areas Journal 11:148-150.

- Thompson, D.Q., R.L. Stuckey, & E.B. Thompson 1987. Spread, impact, and control of purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) in North American wetlands. Research Report No. 2. USDI, Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, DC.

- Twolan-Strutt, L. & P.A. Keddy 1996. Above- and below-ground competition intensity in two contrasting wetland plant communities. Ecology 77(1):259-270.

- Voegtlin, D.J. 1995. Potential of Myzus lythri (Homoptera: Aphididae) to influence growth and development of Lythrum salicaria (Myrtiflorae: Lythraceae). Environmental Entomology 24(3):724-729.

- Weeden, C. R, A. M. Shelton, & M. P. Hoffmann, Eds. 1996. Biological control: A guide to natural enemies in North America. Cornell University. (http://www.nysaes.cornell.edu/ent/biocontrol/weedfeeders/galerucella.html; http://www.nysaes.cornell.edu/ent/biocontrol/weedfeeders/hylobius.html).

- Welling, C.H. & R.L. Becker 1990. Seed bank dynamics of Lythrum salicaria L.: implications for control of this species in North America. Aquatic Botany 38:303-309.

- Wilcox, D.A., M.K. Seeling, & K.R. Edwards 1986. Ecology and management potential for purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria). IN The George Wright Society conference on science in the National Parks. USDI, National Park Service, Washington, DC.

- Wilcox, D.A. 1989. Migration and control of purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria L.) along highway corridors. Environmental Management 13(3):365-370.

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the USGS. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the USGS should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |