Bryde's whale complex

The Bryde's whale complex currently refers to three of nine species is a very large marine mammal, in the family of Rorquals (Balaenoptera), part of the order of cetaceans.

The species within Bryde's are baleen whales, meaning that instead of teeth, they have long plates which hang in a row (like the teeth of a comb) from its upper jaws. Baleen plates are strong and flexible; they are made of a protein similar to human fingernails. Baleen plates are broad at the base (gumline) and taper into a fringe which forms a curtain or mat inside the whale's mouth. Baleen whales strain huge volumes of ocean water through their baleen plates to capture food: tons of krill, other zooplankton, crustaceans, and small fish.

While there now appear to be three whales within this complex, other subpopulations may come to be recognized as distinct species. The IUCN Redlist of Threatened Species describes the situation as follows:

"There is an "ordinary" Bryde's Whale, with a worldwide distribution in the Pacific, Indian and Atlantic oceans, which grows to about 14 m in length, and one or more smaller forms which tend to be more coastal in distribution. The taxonomic status of the smaller forms is unclear."

As of early 2011, three distinct species are recognized:

- Bryde's Whale (Balaenoptera brydei)

- Eden's Whale (Balaenoptera edeni)

- Omura's Whale (Balaenoptera omurai)

Pronounced “broo-dess”, the Bryde's whale is named after Johan Bryde, who helped construct the first South African whaling factory in the early 1900s.

|

Conservation Status |

|

Scientific Classification Kingdom: Animalia |

|

Common Names: |

The Bryde's whale can frequently be found alone or in mother-calf pairs, but on occasion loose aggregations may form, probably due to the proximity of a productive feeding ground. The feeding behaviour of this species is spectacular, and involves the whale lunging forwards through a shoal of fish or krill, mouth opened wide. A vast quantity of prey and water is taken into its mouth, which is accommodated by the expandable region on the underside of the jaw. This is then squeezed back through the closed jaws of the whale, allowing water to escape through the baleen fibres, but trapping food, which is swept off by the huge, rough tongue and swallowed.

The Bryde's whale is one of the livelier rorqual species, frequently breaching clear of the water, and commonly making one to two minute long dives between the surface and depths of 300 metres. Migration patterns vary, with coastal populations in tropical waters appearing to remain in the same location throughout the year, whereas populations in subtropical waters may make limited migrations in response to movements of prey.

In tropical waters, the Bryde's whale may breed throughout the year, while in sub-tropical waters breeding mainly occurs in winter. After a year-long gestation period, a single young is born, already measuring around four metres in length. The Bryde's whale becomes sexually mature at around 8 to 11 years, and has a lifespan of up to 50 years.

Contents

Taxonomy

IUCN notes that:

"B. edeni was originally described by Anderson (1879) from a specimen collected near the Sittang River, Myanmar. . . It was small compared with "ordinary" Bryde’s whales, being apparently nearly physically mature at only 11.3 m in length (Rice 1998). Junge (1950) collected a further specimen (now held in Leiden) at Sugi Island, Indonesia (between Sumatra and Singapore), which he judged to be physically mature and "slightly over" 12 m, and identified it with Anderson's B. edeni.

B. brydei was described by Olsen (1913) from specimens taken off South Africa. Junge (1950) concluded that B. brydei was synonymous with B. edeni. This was accepted by most cetologists and management authorities until the 1990s.

Wada et al. (2003) described a new species, B. omurai, a finding that was confirmed by Sasaki et al. (2006). A source of confusion is that, before its description, specimens of B. omurai were reported as small or "pygmy" Bryde’s Whales (e.g. whales taken in the Solomon Sea (Ohsumi 1978b) and the Philippines (Perrin et al. 1996)). The phylogenetic analyses show clearly that B. omurai lies well outside the Sei/Bryde’s clade: it has a separate entry on this Red List.

Based on phylogenetic analysis, Wada et al. (2003) concluded that B. edeni (represented by Junge’s specimen) also lies outside the clade of Sei and Bryde’s Whales for one mtDNA marker and hence proposed that it be regarded as a separate species, although statistical support for the phylogeny was weak. From an analysis of the full mtDNA genome, Sasaki et al.(2006) concluded that the Junge specimen belongs to a sister clade of the "ordinary" Bryde’s Whales (i.e. more closely related to them than either is to the Sei or Omura's Whale). They agreed that it should be classified as a separate species (B. edeni) from other Bryde's Whales (B. brydei). However, the divergence is relatively shallow, and the two forms could reasonably still be considered subspecies. Data from more markers (including nuclear markers) are needed.

Yoshida and Kato (1999) found that whales from a population of "smallish" Bryde's Whales from southwestern Japan (modal length about one metre shorter than western North Pacific Bryde's Whales – Omura 1962, Ohsumi 1980a) segregated out phylogenetically from other Bryde's Whales in the western North Pacific, and suggested that they may be a subspecies. Sasaki et al. (2006) found that they form a clade with B. edeni (sensu Junge’s specimen)

Best (1977) described a resident inshore form of Bryde's whale off South Africa which is slightly smaller than the "ordinary" form of Bryde’s whale found further offshore around South Africa, and differs in terms of migration, seasonality of reproduction, fecundity and prey types (Best 2001). He noted that Olsen's 1913 description of B. brydei was probably based on a mixture of this inshore form and "ordinary" Bryde's whales caught off South Africa. In the absence of genetic analyses, the taxonomic position of the inshore form remains unclear.

Until more specimens of the putative B. edeni (sensu Sasaki et al. 2006) from more locations have been analysed morphologically and genetically, using more markers, it is too early to settle the taxonomy of the Bryde’s Whale complex: there may be one, two or more species, and/or subspecies, and intermediate forms may be found. In addition, nomenclatural uncertainty remains until the B. edeni holotype (Anderson, 1879) has been analysed genetically."

Physical Description

Bryde's whales are all endothermic and manifest bilateral symmetry. Bryde's whales are often confused with the slightly larger Sei whale (Balaenoptera borealis), but can be distinguished by the three distinctive ridges that run from the tip of the broad rostrum to the rear of the head, level with the two blowholes. Like other rorqual whales, the Bryde's whale has numerous grooves running along the underside of the lower jaw to the belly, which allow this area to expand when the whale swallows water during feeding. The jaws are lined with between 250 and 365 plates of baleen, which bear long, coarse bristles on the inner edge, used for trapping food. The skin of the Bryde's whale is black or dark grey, with white patches on the throat and chin, and may sometimes appear mottled due to pock marks caused by parasites and small sharks. The taxonomic status of the Bryde's whale is currently not totally clear. While there appear to be numerous different forms—occupying separate locations and habitats, and showing variations in size—a consensus has yet to be reached regarding whether they should be classed as subspecies or species.

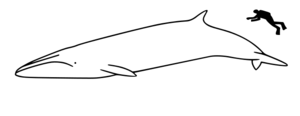

Bryde's whales are dark gray in colour with a yellowish white underside. They are the second smallest rorqual with an average length of 12 meters (m), although the female is usually about one third metre longer than the male; specifically, the length range is 11.9 to 14.6 m for males; 12.2 to 15.6 m for females Body mass of adults varies from 11,300 to 16,200 kilograms. Bryde's whales have two blowholes located on the top of the head. Bryde's whale is often confused with the Sei whale; however, the Bryde's whale has three parallel ridges in the area between the blowholes and the tip of the head. The flippers are small compared to body size. The prominent dorsal fin is sickle shaped. Instead of teeth, these whales have two rows of baleen plates. These plates are located on the top jaw and number approximately 300 on each side. Each baleen plate is short and wide, 50 cm x 19 cm.

Behaviour

Key behaviours of Bryde's whales include natatorial; motile; migratory; sedentary; and social activities. Bryde's whales are seldom seen in large groups but will congregate around dense populations of food. They are deep divers. The lobes of either side of the tail (flukes) are seldom shown. Swimming speed ranges between four to sixteen knots. Some tropical populations are possibly sedentary with short distance migrations. More research needs to be done on the behavior of Bryde's whales.

Reproduction

Key reproductive attributes of the Bryde's whales are: Iteroparous; Year-round breeding; Gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); Sexual reproduction; Viviparous. Breeding occurs year round in Bryde's whales. Sexual maturity is reached at 10 years of age for males and eight years of age for females. The gestation period is approximately 12 months. Most Bryde's whales bear a single calf. Calves are around four metres at birth and body mass of one ton.

Lifespan/Longevity

The maximum longevity recorded in the wild is 72 years of age.

Distribution and Movements

Generally, Bryde’s whale is found worldwide in warm-temperate and tropical waters. Bryde’s whale avoids cold water, unlike most rorquals. Some individuals tend to live in coastal waters; others are migratory and occur well offshore. More specifically, the IUCN notes that:

"Because the number of species or subspecies is still unresolved, and because the different forms are not readily distinguishable at sea, considerable uncertainty remains with regard to the geographic range of each form.

“Ordinary” large-type Bryde’s whales occur in the Pacific, Indian and Atlantic oceans between about 40°N and 40°S or in waters warmer than 16.3°C (Kato 2002). Migration to equatorial waters in winter is documented for the southeast Atlantic population (Best 1996) and for the northwest Pacific population (Kishiro 1996). Migration patterns of other populations are poorly known

They are relatively common in the western North Pacific, mainly north of 20°N in summer and south of 20°N in winter. In the eastern North Pacific, they do not venture north of southern California (US), but there appears to be a resident population in the northern Gulf of California (Urbán and Flores 1996), and they occur throughout the eastern tropical Pacific (Wade and Gerrodette 1993). They occur throughout the tropical Pacific, and across the South Pacific down to about 35°S, but with shifts in distributions between seasons (Miyashita et al. 1995). They occur off the coasts of Peru and Ecuador but not during July to September (Valdivia et al. 1981), and off Chile in an upwelling area between 35°-37°S (Gallardo et al. 1983). In the southwestern Pacific, their distribution extends as far south as the North Island of New Zealand (Thompson et al. 2002).

Bryde’s whales occur throughout the Indian Ocean north of about 35°S. Those in the southern Indian Ocean appear to be large-type animals (Ohsumi 1980b), as are the Bryde’s whales of the northwest Indian Ocean, which were taken illegally by Soviet whaling fleets in the 1960s (Mikhalev 1997), and those around the Maldives (Anderson 2005).

In the South Atlantic, there is a population that summers off the western coast of southern Africa, and migrates to West African equatorial waters in winter (Best 2001). Elsewhere in the Atlantic the distribution of Bryde’s whales is not well known. The Bryde’s whale appears to occur year-round throughout Brazilian waters (Zerbini et al. 1997). Bryde’s whales occur in the Gulf of Mexico (Mullin and Fulling 2004) and throughout the wider Caribbean (Ward et al. 2001). They do not occur in the Mediterranean (Reeves and Notabartolo di Sciara 2006). They have been recorded as far north as Cape Hatteras in the northwest Atlantic (Rice 1998).

East China Sea

Bryde’s whales which occur off southern and southwestern Japan are now considered to belong to an East China Sea population, having earlier been thought to be a local resident population (Kato and Kishiro 1999). Phylogenetic analyses suggest that they are a subspecies of Bryde’s whales (Yoshida and Kato 1999) or belong to the separate species B. edeni (Sasaki et al. 2006).

South African inshore form

There is a resident inshore population of Bryde’s whales off South Africa which shows some morphological differences from ordinary Bryde’s whales (Best 1977, 2001). Its main distribution is between Cape Recife and Saldanha Bay (Best 2001). It may simply be a local form of ordinary Bryde’s whale, but its taxonomic status has yet to be investigated genetically.

Other small forms Small-type “Bryde’s” whales that appear to be mature at small sizes have been found in various Asian waters and off Australia.

The B. edeni holotype (Anderson 1879) was found in the Gulf of Martaban, Andaman Sea. Further specimens were found on the Bay of Bengal coast of Myanmar (Anderson 1879) and in Bangladesh (Andrews 1918). The Junge (1950) specimen, used in recent studies as the genetic representative of B. edeni, is from Sugi Island, Sumatra (Indonesia) (close to Singapore).

A stranding from Hong Kong (China) and a rescued river-trapped individual in eastern Australian (Priddel and Wheeler 1998) have been found to be closely related phylogenetically to the “B. edeni” clade represented by the Junge (1950) specimen and the southwestern Japan whales (Sasaki et al. 2006, LeDuc and Dizon 2002).

Phylogenetic analyses reveal that at least some of the small “Bryde’s whales” taken in the Philippines artisanal fisheries (Perrin et al. 1996) were in fact B. omurai (Sasaki et al. 2006, LeDuc and Dizon 2002).

The identity of “Bryde’s whales” maturing at a small size (11-12 m) caught off western Australia (Bannister 1964) is unclear. They may be a local form, or related to small forms found elsewhere, or they may even have been B. omurai.

The identity of eight small “Bryde’s whales” stranded in Thai waters (Andersen and Kinze 1993) is also unclear."

Food and Feeding Habits

All of the members of Bryde's whale complex are filter feeders. They feed almost exclusively on pelagic fish (pilchard, mackerel, herring, and anchovies) and pelagic crustaceans (shrimp, crab and lobsters). They also have been observed to eat cephalopods (octopus, squid, and cuttlefish).

Threats and Conservation Status

A long standing prohibition on the operation of factory ships north of 40°S, put in place to prevent hunting of rorqual whale's at their lower latitude breeding grounds, allowed the Bryde's whale to escape most of the historical exploitation of rorquals, as it occupies this region all year round. Only populations in the North Pacific may have been affected, as whaling vessels in this region were allowed to operate at lower latitudes, but even this threat was mitigated by the international moratorium on all commercial whaling implemented by the International Whaling Commission (IWC) in 1986. Although pelagic whaling by Japan was subsequently resumed in 2000, it is under scientific permit, and limited to catches of 50 individuals per year. The main concern is that, while assessed as a single species, the Bryde's whale appears to be abundant, but if it is in fact a complex of several separate species, some populations may be so small that they warrant threatened status and require conservation action.

Bryde's whales are not on the Endangered species list. As a result of the 1986 Moratorium on Whaling, they are protected worldwide.

Classified as Data Deficient (DD) on the IUCN Red List and listed on Appendix I of CITES.

The Bryde's whale is included in Appendix I of CITES, making all international trade in this species illegal. With the current moratorium on commercial whaling in place, there appears to be little concern about the survival of this species. However, there is some concern that the moratorium may be lifted, leaving the Bryde's whale open to exploitation.

References

- Balaenoptera brydei (Olsen, 1913), Encyclopedia of Life. Contributors: Elizabeth Gill, University of Michigan; ARKive. Animal Diversity Web (accessed February 18, 2011)

- Reilly, S.B., Bannister, J.L., Best, P.B., Brown, M., Brownell Jr., R.L., Butterworth, D.S., Clapham, P.J., Cooke, J., Donovan, G.P., Urbán, J. & Zerbini, A.N. 2008. Balaenoptera edeni. In: IUCN 2010. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2010.4. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloadedon 04March2011.

- IUCN (2008) Cetacean update of the 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.[1]

- Aguilar, A. 1984. Historical review of catch statistics in Atlantic waters off the Iberian Peninsula. IWC Scientific Committee.

- Anderson, 1994. The Mammals of Texas

- Andersen, M. and Kinze, C. C. 1993. The Brydes whale Balaenoptera edeni Anderson 1878: its distribution in Thai waters with remarks on osteology. 10th Biennial Conference on the Biology of Marine Mammals.

- Anderson, J. 1879. Anatomical and Zoological Researches: Comprising an Account of Zoological Results of the Two Expeditions to Western Yunnan in 1868 and 1875; and a Monograph of the Two Cetacean Genera, Platanista and Orcella. Bernard Quaritch, London, UK.

- Anderson, R. C. 2005. Observations of cetaceans in the Maldives, 1990-2002. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management 7(2): 119-135.

- Andrews, R. C. 1918. A note of the skeletons of Balaenoptera edeni, Anderson, in the Indian Museum, Calcutta. Records of the Indian Museum 15(3): 105-107.v Bannister, J. L. 1964. Australian whaling 1963 catch results and research. Marine Laboratory, Cronulla, Australia.

- Banks, R. C., R. W. McDiarmid, A. L. Gardner, and W. C. Starnes. 2003. Checklist of Vertebrates of the United States, the U.S. Territories, and Canada

- Banks, R. C., R. W. McDiarmid, and A. L. Gardner. 1987. Checklist of Vertebrates of the United States, the U.S. Territories, and Canada. Resource Publication, no. 166. 79

- Best, P. B. 1977. Two allopatric forms of Bryde's whale off South Africa. Reports of the International Whaling Commission Special Issue 1: 10-38.

- Best, P. B. 1996. Evidence of migration by Bryde's whales from the offshore population in the southeast Atlantic. Reports of the International Whaling Commission 46: 315-331.

- Best, P. B. 2001. Distribution and population separation of Bryde's whale Balaenoptera edeni off southern Africa. Marine Ecology Progress Series 220: 277-289.

- Best, P. B., Butterworth, D. S. and Rickett, L. H. 1984. An assessment cruise for the South African inshore stock of Bryde's whales (Balaenoptera edeni). Reports of the International Whaling Commission 34: 403-423.

- Carwardine, M., Hoyt, E., Fordyce, R.E. and Gill, P. (1998) Whales and Dolphins. Harper Collins Publishers, London.

- CITES (April, 2009)[2]

- Dolar, M. L. L., Leatherwood, S., Wood, C. J., Alava, M. N. R., Hill, C. L. and Arangones, L. V. 1994. Directed fisheries for cetaceans in the Philippines. Reports of the International Whaling Commission 44: 439-449.

- Felder, D.L. and D.K. Camp (eds.), Gulf of Mexico–Origins, Waters, and Biota. Biodiversity. Texas A&M Press, College Station, Texas

- Gallardo V. A., Arcos D., Salamanca, M. and Pastene, L. 1983. On the occurrence of Bryde’s whales (Balaenoptera edeni Anderson 1878) in an upwelling area off central Chile. Reports of the International Whaling Commission 33: 481-488.

- Gordon, D. (Ed.) (2009). New Zealand Inventory of Biodiversity. Volume One: Kingdom Animalia. 584 pp

- International Fund for Animal Welfare - Stop Whaling(April, 2009)

- International Whaling Commission. 1974. Scientific Committee on Sei and Bryde's Whales.. Cambridge.

- International Whaling Commission. 1980. Report of the sub-committee on Bryde’s whales. Report of the International Whaling Commission 30: 64-73.

- International Whaling Commission. 1981. Report of the subcommittee on other baleen whales. Report of the International Whaling Commission 31: 122-132.

- International Whaling Commission. 1983. Chairman’s report of the 34th Annual Meeting. Report of the International Whaling Commission 33: 20-42.

- International Whaling Commission. 1996. Report of the subcommittee on North Pacific Bryde’s whales. Report of the International Whaling Commission 46: 147-159.

- International Whaling Commission. 1997. Report of the subcommittee on North Pacific Bryde’s whales. Report of the International Whaling Commission 47: 163-168.

- International Whaling Commission. 2006. Report of the workshop on the pre-implementation assessment of western North Pacific Bryde’s whales. Journal of Cetcaean Research and Management 8: 337-355.

- International Whaling Commission. 2006. The IWC Summary Catch Database.

- International Whaling Commission. 2007. Western North Pacific Bryde’s whale implementation: report of the first intersessional workshop. Journal of Cetcaean Research and Management 9: in press.

- Jefferson, T.A., S. Leatherwood and M.A. Webber. 1993. Marine mammals of the world. FAO Species Identification Guide. Rome. 312 p.

- Junge, G. C. A. 1950. On a specimen of the rare fin whale, Balaenoptera edeni Anderson, stranded on Pulu Sugi near Singapore. Zoologische Verhandelingen 9: 26.

- Kato, H. 2002. Bryde's whale Balaenoptera edeni and B. brydei. In: W. F. Perrin, B. Wursig and J. G. M. Thewissen (eds), Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, pp. 171-177. Academic Press.

- Kato, H. and Kishiro, T. 1999. Bryde's whales off Kochi, south west Japan, with new information from off southwest Kyushu (East China Sea). International Whaling Commission Scientific Committee.

- Kawamura, A. 1977. On the food of Bryde's whales caught in the South Pacific and Indian Oceans. Scientific Reports of the Whales Research Institute 29: 49-58.

- Kishiro, T. 1996. Movements of marked Bryde's whales in the western North Pacific. Reports of the International Whaling Commission 46: 421-428.

- Kondo, I. and Kasuya, T. 2002. True catch statistics for a Japanese coastal whaling company in 1965-78. International Whaling Commission Scientific Committee.

- Leduc, R. G. and Dizon, A. E. 2002. Reconstructing the rorqual phylogeny: with comments on the use molecular and morphological data for systematic study. In: C. J. Pfeiffer (ed.), Molecular and Cell Biology of Marine Mammals, pp. 100-110. Kreiger Publishing Company, Florida, USA.

- Longevity Records: Life Spans of Mammals, Birds, Amphibians, Reptiles, and Fish

- Martin, A.R. (1990) Whales and Dolphins. Salamander Books Ltd, London.

- Mead, James G., and Robert L. Brownell, Jr. / Wilson, Don E., and DeeAnn M. Reeder, eds. 2005. Order Cetacea. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 3rd ed., vol. 1. 723-743

- Mikhalev Yu. A. 1997. Bryde's whales of the Arabian Sea and adjacent waters. International Whaling Commission Scientific Committee.

- Miyashita, T., Kato, H. and Kasuya, T. 1996. Worldwide Map of Cetacean Distribution Based on Japanese Sighting Data. National Research Institute of Far Seas Fisheries.

- Mullin, K. D. and Fulling, G. L. 2004. Abundance of cetaceans in the oceanic northern Gulf of Mexico, 1996-2001. Marine Mammal Science 20(4): 787-807.

- Nowak, R.M. (1999) Walker's Mammals of the World: Volume 2. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland.

- Ohsumi, S. 1978. Bryde’s whales in the North Pacific in 1976. Reports of the International Whaling Commission 28: 277-280.

- Ohsumi, S. 1978. Provisional report on Bryde’s whales caught under special permit in the Southern Hemisphere. Reports of the International Whaling Commission 28: 281-288.

- Ohsumi, S. 1980. Bryde’s whales in the North Pacific in 1978. Reports of the International Whaling Commission 30: 315-318.

- Ohsumi, S. 1980. Population study of the Bryde’s whale in the Southern Hemisphere under scientific permit in the three seasons, 1976/77 - 1978/79. Reports of the International Whaling Commission 30: 319-331.

- Olsen, O. 1913. On the external characters and biology of Bryde’s whales (Balaenoptera brydei), a new rorqual from the coast of South Africa. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1913: 1073-1090.

- Omura, H. 1962. Further information on Bryde's whale from the coast of Japan. Scientific Reports of the Whales Research Institute 16: 7-18.

- Omura, H. 1977. Review of the occurrence of Bryde's whale in the Northwest Pacific. Reports of the International Whaling Commission 1: 88-91.

- Perrin, W. E., Dolar, M. L. L. and Ortega, E. 1996. Osteological comparison of Bryde's whales from the Philippines with specimens from other regions. Report of the International Whaling Commission 46: 409-413.

- Perrin, W. (2010). Balaenoptera edeni Anderson, 1878. In: Perrin, W.F. World Cetacea Database. Accessed through: Perrin, W.F. World Cetacea Database. 2011-02-05

- Priddell, D. and Wheeler, R. 1998. Hematology and blood chemistry of a Bryde's whale, Balaenoptera edeni, entrapped in the Manning River, New South Wales, Australia. Marine Mammal Science 14(1): 72-81.

- Ramos, M. (ed.). 2010. IBERFAUNA. The Iberian Fauna Databank

- Reeves, R. R. 2002. The origins and character of 'aboriginal subsistence' whaling: a global review. Mammal Review 32: 71-106.

- Reeves, R. R. and Notarbartolo Di Sciara, G. 2006. The status and distribution of cetaceans in the Black Sea and Mediterranean Sea. IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, Malaga, Spain.

- Rice, D. W. 1998. Marine mammals of the world: systematics and distribution. Society for Marine Mammalogy.

- Sasaki, T., Nikaido, M., Wada, S., Yamada, T. K., Cao, Y., Hasegawa, M. and Okada, N. 2006. Balaenoptera omurai is a newly discovered baleen whale that represents an ancient evolutionary lineage. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 41: 40-52.

- Thompson, K. F., O’Callaghan, T. M., Dalebout, M. L. and Baker, C. S. 2002. Population eceology of Bryde’s whales (Balaenoptera edeni sp.) in the Haurake Gulf, New Zealand: preliminary observations. International Whaling Commission Scientific Committee.

- Tønnessen J. N. and Johnsen A. O. 1982. The History of Modern Whaling. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA, USA.

- UNESCO-IOC Register of Marine Organisms

- Urban-Ramirez, J. and Flores-R., S. 1996. A note on Bryde's whales (Balaenoptera edeni) in the Gulf of California, Mexico. Reports of the International Whaling Commission 46: 453-458.

- Valdivia, J., Franco, F. and Ramirez, P. 1981. The exploitation of Bryde’s whales in the Peruvian Sea. Reports of the International Whaling Commission 31: 441-448.

- Wada, S., Oishi, M. and Yamada, T. K. 2003. A newly discovered species of living baleen whale. Nature 426: 278-281.

- Wade, P. R. and Gerrodette, T. 1993. Estimates of cetacean abundance and distribution in the eastern tropical Pacific. Reports of the International Whaling Commission 43: 477-493.

- Ward, N., Moscrop, A. and Carlson, C. 2001. Elements for the development of a Marine Mammal Action plan for the wider Caribbean: a review of marine mammal distribution. Available at: www.cep.unep.org/meetings-repository/SPAW COP/English Docs/IG20-inf3en.doc.

- Williamson, G. R. 1975. Minke whales off Brazil. Scientific Reports of the Whales Research Institute 27: 37-59.

- Yoshida, H. and Kato, H. 1999. Phylogenetic relationships of Bryde's whales in the western North Pacific and adjacent waters inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequences. Marine Mammal Science 15(4): 1269-1286.

- Wilson, Don E., and DeeAnn M. Reeder, eds. 1993. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 2nd ed., 3rd printing. xviii + 1207

- Zerbini, A. N., Secchi, E. R., Siciliano, S. and Simoes-Lopes, P. C. 1997. A review of the occurrence and distribution of whales of the genus Balaenoptera along the Brazilian coast. Reports of the International Whaling Commission 47: 407-417.

- van der Land, J. (2001). Tetrapoda, in: Costello, M.J. et al. (Ed.) (2001). European register of marine species: a check-list of the marine species in Europe and a bibliography of guides to their identification. Collection Patrimoines Naturels, 50: pp. 375-376