Narwhal

The Narwhal (scientific name: Monodon monoceros) is one of two species of cetaceans in the family of white whales (Monodontidae); the other being the Beluga. Noted for its unicorn-like single tusk, Narwhals have inspired legends in many cultures and throughout history have been revered across the world.

Narwhal Source: National Institute of Standards and Technology Narwhal Source: National Institute of Standards and Technology

|

|

Scientific Classification Kingdom: Animalia |

The smooth, white tusk is normally found only on males and is the result of extreme growth of the left elongated maxillary tooth that protrudes through the upper lip in a spiral form. Narwhals have just two teeth, both in the upper jaw. Usually the right tooth remains small and the left one grows to become the tusk. It is believed by the majority of the scientific community that the tusk is a secondary sexual characteristic and probably play a role in breeding competition. Females occasionally grow a tusk and males have been seen with two, or none. The largest tusk ever measured was a massive 267 centimetres.

Narwhals have a conical body shape and flexible neck with a mottled blue, black, grey and white body fading onto the underside. Older males can be distinguished by their white bodies with mottling only on the top of the back. The dorsal fin is just a low, inconspicuous ridge and the tail fin is concave .

Historically narwhals were a staple food source of many Arctic peoples. Arctic people used the narwhals body for a number of other uses. The blubber can be rendered for oil, the sinew used as thread, and the tusks traded and carved.

Narwhals are thought to migrate annually and in very large groups, moving to spend the winter within the heavy pack ice of the Arctic and summering in deep sounds and fjords. They make deep dives - satellite transmitters are beginning to provide information on their diving habits - and feed near the bottom, probably capturing their prey by suction and swallowing it whole. Killer whales and polar bears are predators, and humans hunt them for their skin, meat, and ivory tusks.

Narwhals live in groups of two to ten individuals which may congregate with other groups to form herds of hundreds of individuals . They move very slowly and erratically when hunting, searching for fish, squid and shrimps during dives of between seven and 20 minutes.

They are very vocal, clicking and squeaking whilst travelling. Like many cetaceans, surfacing Narwhals slap their flippers against the surface and raise their heads and tusks out of the water. Predators of Narwhals include Greenland sharks, Orcas, Polar bears and Walruses .

Mating takes place between March and May and gestation lasts around 15 months, with births in July and August of the following year. The calves are born tail first and males do not grow their tusks until they have been weaned at around one year of age. Females give birth just once every three years .

Contents

Physical Description

The species displays sexual dimorphism, with males being larger. Other physical features are: Endothermic; Homoiothermic; Bilateral symmetry. Head and body length, exclusive of the tusk, is 360 to 620 centimetres, pectoral fin length is 30 to 40 cm, and expanse of the tail flukes is 100 to 120 cm. According to Reeves and Tracey (1980) average head and body length is about 470 cm in males and 400 cm in females and average weight is 1600 kilograms in males and 960 kilograms in females. About one-third of the body mass is blubber.

Mottled black and white (young are gray); colouration becomes paler with age. Adults have brownish or dark grayish upper parts and whitish underparts, with a mottled pattern of spots throughout. The head is relatively small, the snout blunt, and the flipper is short and rounded. There is no dorsal fin, but there is an irregular doral ridge about five cm high and 60 to 90 cm long on the posterior half of the back. The posterior margins of the tail flukes are strongly convex, rather than concave or straight as in most cetaceans.

There are only two teeth, both in the upper jaw. In females the teeth usually are not functional and remain embedded in the bone. In males the right tooth remains embedded, but the left tooth erupts, protrudes through the upper lip, and grows forward in a counterclockwise spiral pattern to form a long, straight tusk. The tusk is about one-third to one-half as long as the head and body. In rare cases the right tooth also forms a tusk, but both tusks are always twisted in the same direction. Occasionally one or even two tusks develop in a female. The distal end of the tusk has a polished appearance, and the remainder is usually covered by a reddish or greenish growth of algae. There is an outer layer of cement, an inner layer of dentine, and a pulp cavity that is rich in blood. Broken tusks are common, but the damaged end is filled by new dentine growth (Reeves & Tracey, 1980).

Behaviour

Key behaviours are: motile; migratory; social. Narwhals are a gregarious species commonly found in pods of six to twenty individuals, though most groups tend to have three to eight individuals. These groups are often segregated by sex, with pods of male 'bachelors' being common. The smaller groups tend to gather together during migration seasons to form herds of hundreds or even thousands. Narwhals remain in the vicinity of pack ice throughout the year. Breathing holes are maintained through sheets of ice by thrusts of the thick melon, sometimes by several animals at once.

There are various hypotheses for the function of the tusk. Narwhals may use it like male deer, for male-male competition. It also may be used to spear food. During deep dives, the tusk may be helpful in stirring up food from bottom sediments. Since most females are tuskless, the most likely hypothesis is that the tusk is a secondary sexual characteristic and may be the result of sexual selection by females (Reeves & Tracey, 1991).

Reproduction

Key reproductive features are: Iteroparous; Seasonal breeding; Gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); Sexual; Fertilization; Fertilization; Internal; Viviparous. The gestation period is about 15.3 months, with mating occurring in March-May and calving in July-August of the following year. Lactation duration is unknown, but thought to be comparable to the white whale (Delphinapterus leucas) of 20 months. The interval between successive conceptions is normally three years. Monodon monoceros copulate vertically in the water, belly to belly. Infant Narwhals are usually implanted in the left uterine horn.

A single calf is often the result of gestation, yet some twins have been recorded. Birth takes place tail first (Klinowska, 1991). The newborn is born with 25 mm of blubber. Calves usually measure between 1.5 and 1.7 m and weigh 80 kg. Physical maturity is attained at a length of four metres and abody mass of 900 kg in females and 4.7 m and 1600 kg in males. Physical maturation usually corresponds to four to seven years of age (Reeves & Tracey, 1980). Young narwhals are capable of swimming soon after birth. They are nursed and protected by their mothers for extended periods after birth.

Lifespan/Longevity

Size at birth 1.5 metres (15 feet); Sexual maturity at five to seven years; Females have calves every threeyears; Longevity over 60 years, possibly more than 100; Behavior; Vocal and gregarious

Narwhals may live to an age of over 50 in the wild, yet attempts at captive breeding have been unsuccessful. Upon reaching the captive establishment, Narwhals have only survived from one to four months. Considering the adult male can grow to 7m long, the species is usually too big to keep in captivity except at the largest of establishments (Klinowska, 1991).

Distribution and Movements

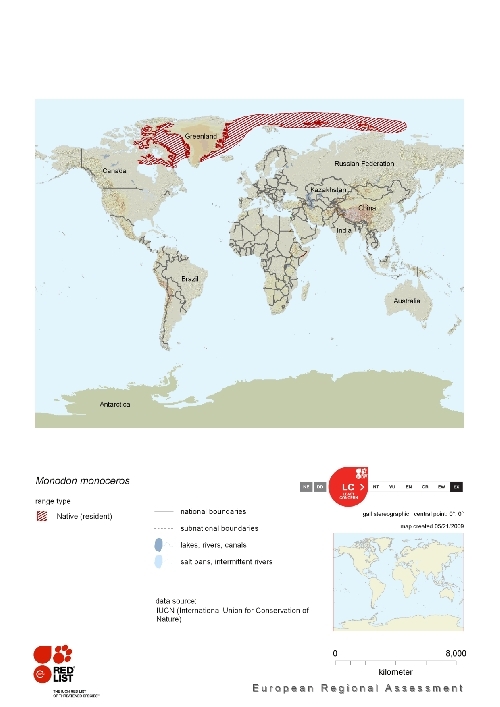

The Narwhal occurs patchily throughout Arctic waters and in the north Atlantic Ocean. The highest narwhal density is found in the eastern Canadian Arctic Ocean and Greenland. It is also found in the waters of Iceland, Svalbard in Norway, Alaska (US), and Russia .

The Narwhal occurs patchily throughout Arctic waters and in the north Atlantic Ocean. The highest narwhal density is found in the eastern Canadian Arctic Ocean and Greenland. It is also found in the waters of Iceland, Svalbard in Norway, Alaska (US), and Russia .

The IUCN Red List notes:

Narwhals primarily inhabit the Atlantic sector of the Arctic. The principal distribution is from the central Canadian Arctic (Peel Sound – Prince Regent Inlet and northern Hudson Bay) eastward to Greenland and into the eastern Russian Arctic (around 180°E). They are rarely observed in the far eastern Russian Arctic, Alaska, or the western Canadian Arctic.

In summer, narwhals spend approximately two months in high Arctic ice-free shallow bays and fjords; they overwinter in offshore, deep, ice-covered habitats along the continental slope (Heide-Jørgensen and Dietz 1995). The whales migrate annually between these disjunct seasonal areas of concentration, with the migratory periods lasting approximately two months (Koski and Davis 1994; Innes et al. 2002; Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2002; Dietz et al. 2001; Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2003).

And:

The global population is probably in excess of 80,000 animals. The Narwhals that summer in the Canadian High Arctic constitute the largest fraction, probably in excess of 70,000 animals (Innes et al. 2002; NAMMCO/JCNB 2005). In addition, some thousands of narwhals probably summer in the bays and fjords along the East Baffin Island coastline (NAMMCO/JCNB 2005). Another summering aggregation, centred in northern Hudson Bay, numbers about 3,500 animals (COSEWIC 2004). Two summering aggregations in West Greenland (Inglefield Bredning and Melville Bay) total over 2,000 animals (Heide-Jørgensen 2004; NAMMCO/JCNB 2005) and in East Greenland a rough estimate of the total number of animals in the summering aggregations is greater than 1000 (Gjertz 1991; NAMMCO/JCNB 2005). Surveys in Central West Greenland in late winter estimated 2,800 animals in 1998 and 1999 (Heide-Jørgensen and Acquarone 2002), however, these surveys covered unknown proportions of whales from different summering aggregations in West Greenland (likely Inglefield Bredning) and possibly Canada. Some areas in Canada with summering aggregations remain unsurveyed, although these likely contain small numbers.

The estimated generation length for the narwhal according to Taylor et al. (2007) is 24 years, which means that the 3-generation window is 1936-2008.

Habitat

The Narwhal occupies one of the most northerly habitats of any cetacean species, between 70°N and 80°N in the polar region, and seems to have more specific habitat requirements, and thus a more restricted range, than other cetaceans; however, this taxon is found both in coastal waters as well as pelagic environments. Narwhals are rarely found far from loose pack ice and they prefer deep water. There are large concentrations in the Davis Strait, around Baffin Bay, and in the Greenland Sea. The advance and retreat of the ice initiates migration.

During summer, Narwhals occupy deep bays and fjords; the best known and probably largest narwhal population in the world inhabits the deep inlets, sounds and channels of the eastern Canadian Arctic and north-west Greenland. When ice cover is low in larger, deeper water bodies, they move to smaller water bodies, which are steep-sided and deep. These traditional summering areas at the heads of fjords are probably important areas for calving. The Narwhal’s preference for deep water in summer separates them from [[Beluga] whales] which spend the summer mainly in shallow estuaries and bays (Klinowska, 1991).

Feeding Habits

Narwhals have a varied diet, feeding upon squid, fish and crustaceans. With few functional teeth this mammal is thought to use suction and the emission of a jet of water to dislodge prey such as bottom:living fish and molluscs. Their highly flexible necks aid in scanning a broad area and the capture of more mobile prey. Specific prey taken include: Polar cod, Greenland halibut, flounder, salmon, herring, crustaceans and cephalopods (octopuses and squids).

Predation

Some have suggested that the tusk is used for anti-predatory functions, this is unsupported by evidence. Nonetheless, the tusk, which can grow to three metres, could be a formidable weapon.

Economic Importance for Humans

Hunted by the Inuit as a subsistence food, narwhals are also hunted for their ivory tusks which are sold as curios or to be carved. The price of Narwhal ivory has increased significantly since the 1970s and continues to rise. Narwhals may also be susceptible to climate fluctuations and long-term climate change. Narwhals are known to have been trapped under fast-forming ice, preventing them from forming a breathing hole .

Threats and Conservation Status

Classified as Near Threatened (NT) on the IUCN Red List and listed on Appendix II of CITES . It is also listed on Appendix II of the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS or Bonn Convention) and on Appendix II of the Berne Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats .

In 1976 the Narwhal Protection Regulations were produced as part of the Canadian Fisheries Act. It contained legislation that required fishing to be limited to quotas, conferring total protection onto mothers and calves, requiring that full use be made of narwhal carcasses, and requiring the full labelling of every tusk obtained. However, these regulations are sometimes poorly enforced. The narwhal is protected in the United States, although the Inuit are exempt from these laws for subsistence hunting only. It is fully protected in Russia and Norway, and quotas limit the catch in west Greenland. Laws requiring the declaration of narwhal catch, both intentional and by-catch, are necessary throughout this species' range .

The IUCN Red List notes:

Narwhal populations are potentially threatened by hunting, climate change, and industrial activities. Narwhals were never the targets of large-scale commercial hunting except for a brief period of perhaps several decades of the early 20th century in the eastern Canadian Arctic (Mitchell and Reeves 1981). They were hunted opportunistically by commercial whalers, explorers and adventurers in many areas. For many centuries, narwhals have been hunted by the Inuit for human food, dog food and tusk ivory (Born et al. 1994). The mattak (skin and adhering blubber) is highly prized as food and provides a strong incentive for the hunt (Reeves 1993), but in recent years the cash value of ivory and the need for cash to buy snowmobiles have both greatly increased. Potential future threats include habitat degradation from oil exploration and development (e.g., in West Greenland) and increased shipping in the high Arctic (NW and NE passages).

In West Greenland, catches have declined since 1993 with no significant sex bias. Heide-Jorgensen (2002) estimated the annual catch rate at 550 between 1993 and 1995. In 2004, the estimated catch in West Greenland was 294 (NAMMCO/JCNB 2005), including whales that were struck and lost. In contrast to West Greenland, there has been an 8% increase in catches in East Greenland since 1993 (NAMMCO/JCNB 2005).

The narwhal is actively hunted only in Canada and Greenland. In the eastern Canadian Arctic, the average reported landed catch per year from selected communities was 373 between 1996 and 2004 (NAMMCO/JCNB 2005). In Canada the majority of the communities take a greater proportion of males than females throughout the seasons. Annual catch statistics in Canada substantially underestimate the total numbers of narwhals killed due primarily to the incomplete reporting of whales that are struck and killed but lost (IWC 2000; NAMMCO/JCNB 2005; Nicklen 2007).

Narwhals supplied various staples in the traditional tribal subsistence economy. Today the main products are mattak and ivory (Reeves 1993; Reeves and Heide-Jørgensen 1994; Heide-Jørgensen 1994; Nicklen 2007). Narwhal tusks from Canada and Greenland are sold in specialty souvenir markets domestically and also have been exported. However, in Greenland, the export of tusks is currently banned. In Canada, the quota system that had been in place since the 1970s was replaced by a community-based management system implemented in the late 1990s and early 2000s (COSEWIC 2004). The hunt is managed by local hunter and trapper organizations with harvest limits established in some communities. Compliance has been questionable (COSEWIC 2004). Under this system, removals from some summering aggregations are probably sustainable, however, there is concern that removals from other summering aggregations may not be (NAMMCO/JCNB 2005). In Greenland, a quota system was introduced in 2004 by the Greenland Ministry of Fisheries and Wildlife. The quota was set at 300 narwhals (of which 294 were taken), divided among municipalities of West Greenland. Compliance reportedly has been good (NAMMCO/JCNB 2005) although there is concern that catch limits may be set too high (IWC 2007, p. 52).

Narwhals are well adapted to a life in the pack ice as indicated by the fact that there is very little open water in their winter habitat (Laidre and Heide-Jørgensen 2005b). They spend much of their time in heavy ice and are vulnerable to ice entrapments where hundreds can become trapped in a small opening in the sea ice (savssat) and die. This occurs when sudden changes in weather conditions (such as shifts in wind or quick drops in temperature) freeze shut leads and cracks they were using. When entrapped whales are discovered by hunters, they normally are killed. A recent assessment of the sensitivity of all Arctic marine mammals to climate change ranked the Narwhal as one of the three most sensitive species, primarily due to its narrow geographic distribution, specialized feeding and habitat choice, and high site fidelity (Laidre et al. in press). Thus an argument can be made that any reduction of sea ice may be beneficial to narwhals.

References

- Jefferson, T.A., Karczmarski, L., Laidre, K., O’Corry-Crowe, G., Reeves, R.R., Rojas-Bracho, L., Secchi, E.R., Slooten, E., Smith, B.D., Wang, J.Y. & Zhou, K. 2008. Monodon monoceros. In: IUCN 2010. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2010.4. . Downloaded on 06 April 2011.

- Macdonald, D. (2001) The New Encyclopedia of Mammals. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Culik, B.M. (2002) Review on Small Cetaceans: Distribution, Migration and Threats. UNEP/CMS Secretariat, Bonn, Germany.

- MarineBio.org (April, 2005)

- Heide-Jørgensen, M.P. (2008) Pers. Comm.

- Cetaceans of the World (May, 2005)

- Banks, R. C., R. W. McDiarmid, A. L. Gardner, and W. C. Starnes. 2003. Checklist of Vertebrates of the United States, the U.S. Territories, and Canada

- Banks, R. C., R. W. McDiarmid, and A. L. Gardner. 1987. Checklist of Vertebrates of the United States, the U.S. Territories, and Canada. Resource Publication, no. 166. 79

- Born, E. W., Heide-Jørgensen, M. P., Larsen, F. and Martin, A. R. 1994. Abundance and stock composition of narwhals (Monodon monoceros) in Inglefield Bredning (NW Greenland). Meddelelser om Gronland Bioscience 39: 51-68.

- Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. 2004. Assessment and update status report on the narwhal Monodon monoceros in Canada. Ottawa, Canada Available at: www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm.

- Dietz, R., Heide-Jørgensen, M. P., Richard, P. R. and Acquarone, M. 2001. Summer and fall movements of narwhals (Monodon monoceros) from northeastern Baffin Island towards northern Davis Strait. Arctic 54: 244-261.

- Gjertz, I. 1991. The narwhal, Monodon monoceros, in the Norwegian high arctic. Marine Mammal Science 7: 402-408.

- Hay, K. A. and Mansfield, A. W. 1989. Narwhal Monodon monoceros Linneaus, 1758. In: S. H. Ridgway and R. Harrison (eds), Handbook of marine mammals, pp. 145-176. Academic Press, London, UK.

- Heide-Jørgensen, M. P. 1994. Distribution, exploitation and population status of white whales (Delphinapterus leucas) and narwhals (Monodon monceros) in West Greenland. Meddelelser om Gronland Bioscience 39: 135-150.

- Heide-Jørgensen, M. P. 2002. Narwhal Monodon monoceros. In: W. F. Perrin, B. Wursig and J. G. M. Thewissen (eds), Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, pp. 783-787. Academic Press, San Diego, USA.

- Heide-Jørgensen, M. P. 2004. Aerial digital photographic surveys of narwhals, Monodon monoceros, in northwest Greenland. Marine Mammal Science 20: 246-261.

- Heide-Jørgensen, M. P. and Aquarone, M. 2002. Size and trends of bowhead whales, beluga and narwhal stocks wintering off West Greenland. NAMMCO Scientific Publications 4: 191-210.

- Heide-Jørgensen, M. P. and Dietz, R. 1995. Some characteristics of narwhal, Monodon monoceros, diving behaviour in Baffin Bay. Canadian Journal of Zoology 73: 2106-2119.

- Heide-Jørgensen, M. P., Dietz, R., Laidre, K. L. and Richard, P. 2002. Autumn movements, home ranges, and winter density of narwhals (Monodon monoceros) tagged in Tremblay Sound, Baffin Island. Polar Biology 25: 331-341.

- Heide-Jørgensen, M. P., Richard, P., Dietz, R., Laidre, K. L., Orr, J. and Schmidt, H. C. 2003. An estimate of the fraction of belugas (Delphinapterus leucas) in the Canadian High Arctic that winter in West Greenland. Polar Biology 26: 318-326.

- Innes, S., Heide-Jørgensen, M. P., Laake, J. L., Laidre, K. L., Cleator, H. J., Richard, P. and Stewart, R. E. A. 2002. Surveys of belugas and narwhals in the Canadian High Arctic in 1996. NAMMCO Scientific Publications 4: 169-190.

- International Whaling Commission. 2002. Report of the Standing Sub-Committee on Small Cetaceans. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management 4: 325-338.

- International Whaling Commission. 2007. Report of the Scientific Committee. Journal of Cetcaean Research and Management 9: 1–73.

- IUCN (2008) Cetacean update of the 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- Klinowska, M. 1991. Dolphins, Porpoises and Whales. The IUCN Red Data Book. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

- Koski, W. R. and Davis, R. A. 1994. Distribution and numbers of narwhals (Monodon monoceros) in Baffin Bay and Davis Strait. Meddelelser om Gronland Bioscience 39: 15-40.

- Laidre, K. L. and Heide-Jørgensen, M. P. 2005. Arctic sea ice trends and narwhal vulnerability. Biological Conservation 121: 509-517.

- Laidre, K. L. and Heide-Jørgensen, M. P. 2005. Winter feeding intensity of narwhals (Monodon monoceros). Marine Mammal Science 21: 45-57.

- Laidre, K. L., Heide-Jørgensen, M. P. and Dietz, R. 2002. Diving behaviour of narwhals (Monodon monoceros) at two coastal localities in the Canadian High Arctic. Canadian Journal of Zoology 80: 624-635.

- Laidre, K. L., Heide-Jørgensen, M. P., Dietz, R., Hobbs, R. C. and Jorgensen, O. A. 2003. Deep diving by narwhals Monodon monoceros: Differences in foraging behavior between wintering areas? Marine Ecology Progress Series 261: 269-281.

- Laidre, K. L., Heide-Jørgensen, M. P., Jorgensen, O. A. and Treble, M. A. 2004. Deep-ocean predation by a high Arctic cetacean. ICES Journal of Marine Science 61: 430-440.

- Laidre, K. L., Stirling, I., Lowry, L.F., Wiig, Ø., Heide-Jørgensen, M. P. and Ferguson, S.H. 2008. Quantifying the sensitivity of Arctic marine mammals to climate-induced habitat change. Ecological Applications 18 (Supplement: Arctic Marine Mammals): 97-125.

- Linda Geddes. 2005. What's the point of the narwhal's tusk?. New Scientist. 188(2531/2532):

- Linnaeus, C., 1758. Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classis, ordines, genera, species cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tenth Edition, Laurentii Salvii, Stockholm, 1:75, 824 pp.

- MEDIN (2011). UK checklist of marine species derived from the applications Marine Recorder and UNICORN, version 1.0.

- Margaret Klinowska (1991) Dolphins, Porpoises and Whales. The IUCN Red Data Book. IUCN: Gland, Switzerland.

- Mead, James G., and Robert L. Brownell, Jr. / Wilson, Don E., and DeeAnn M. Reeder, eds. 2005. Order Cetacea. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 3rd ed., vol. 1. 723-743

- Minasian, S. 1986. The World's Whales. New York: Academic Press.

- Mitchell, E. and Reeves, R. R. 1981. Catch history and cumulative catch estimates of inital population size of cetaceans in the eastern Canadian Arctic. Reports of the International Whaling Commission 31: 645-682.

- Nicklen, P. 2007. Arctic ivory: hunting the narwhal. National Geographic 212: 110-129.

- North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission. 2005. Report of the Joint Meeting of the NAMMCO Scientific Committee Working Ground on the population status of narwhal and beluga in the North Atlantic and the Canada/Greenland Joint Commission on Consercation and Management of Narwhal and Beluga Scientific Working Group. North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission, Nuuk, Greenland.

- Perrin, W. (2011). Monodon monoceros Linnaeus, 1758. In: Perrin, W.F. World Cetacea Database. Accessed through: Perrin, W.F. World Cetacea Database at http://www.marinespecies.org/cetacea/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=137116 on 2011-03-18

- Reeves, R., S. Tracey. 1980. *Monodon monoceros*. Mammalian Species, 127: 1-7.

- Reeves, Randall R., and Sharon Tracy. 1980. Monodon monoceros. Mammalian Species, no. 127. 1-7

- Reeves, R. R. 1993. Domestic and international trade in narwhal products. TRAFFIC Bulletin 14: 13-20.

- Reeves, R. R. and Heide-Jørgensen, M. P. 1994. Commercial aspects of the exploitation of narwhals (Monodon monoceros) in Greenland, with emphasis on tusk exports. Meddelelser om Gronland Bioscience 39: 119-134.

- Rice, Dale W. 1998. Marine Mammals of the World: Systematics and Distribution. Special Publications of the Society for Marine Mammals, no. 4. ix + 231

- UNESCO-IOC Register of Marine Organisms

- Wilson, Don E., and DeeAnn M. Reeder, eds. 1993. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 2nd ed., 3rd printing. xviii + 1207

- Wilson, Don E., and F. Russell Cole. 2000. Common Names of Mammals of the World. xiv + 204

- Wilson, Don E., and Sue Ruff, eds. 1999. The Smithsonian Book of North American Mammals. xxv + 750

- van der Land, J. (2001). Tetrapoda, in: Costello, M.J. et al. (Ed.) (2001). European register of marine species: a check-list of the marine species in Europe and a bibliography of guides to their identification. Collection Patrimoines Naturels, 50: pp. 375-376