Marine debris

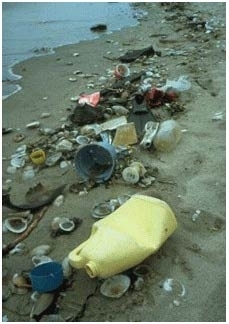

Marine debris is typically defined as any human-made object discarded, disposed of, or abandoned that enters the coastal or marine environment. It may enter directly from a ship, or indirectly when washed out to sea via rivers, streams and storm drains. Objects ranging from detergent bottles, hazardous medical wastes, and discarded fishing line all qualify as marine debris. In addition to being unsightly, it poses a serious threat to everything with which it comes into contact. Marine debris can be life-threatening to marine organisms and humans and can wreak havoc on coastal communities and the fishing industry.

Contents

Types of marine debris

As society has developed new uses for plastics, the variety and quantity of plastic items found in the marine environment has increased dramatically. These products range from common domestic material (bags, cups, bottles, balloons) to industrial products (strapping bands, plastic sheeting, hard hats, resin pellets) to lost or discarded fishing gear (nets, buoys, traps, lines).

Thousands of abandoned and derelict vessels litter ports, waterways and estuaries, creating a threat to navigation, recreation, and the environment. Many vessels end up sinking at moorings, semi-submerged in the intertidal zone, or stranding on shorelines, on reefs or in marshes, and breaking apart. In protected harbors and bays these vessels may persist for years, while in open, exposed coastal environments the debris from disintegrating vessels may be widespread along shorelines and across underwater habitats.

Glass, metal, and rubber are similar to plastic in that they are used for a wide range of products. While they can be worn away – torn into smaller and smaller fragments – they generally do not biodegrade entirely. As these materials are used commonly in our society, their occurrence as marine debris is overwhelming

Sources of Marine Debris

There are two sources of marine debris. The first is from the land and includes users of the beach, storm water-runoff, landfills, municipal solid waste, rivers, and streams, floating structures, ill-maintained garbage bins and dumps and litterbugs. Marine debris also comes from combined sewer overflows, and storm drains. Typical debris from these sources includes medical waste, street litter and sewage. Land-based sources cause 80% of the marine debris found on our beaches and waters.

The second source of marine debris is from ocean sources, and this type of debris includes galley waste and other trash from ships, recreational boaters and fishermen and offshore oil and gas exploration and production facilities. Derelict fishing gear (DFG) is nets, lines, crab/shrimp pots, and other recreational or commercial fishing equipment that has been lost, abandoned, or discarded in the marine environment. Modern gear is generally made of synthetic materials and metal, and lost gear can persist for a very long time.

Debris generated on both land and marine vessels can become marine debris during and as a result of extreme environmental conditions. Hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, tsunami and mudslides have devastating effects on human life and property. The high winds, heavy rains, flooding, and tidal surge associated with extreme weather events are capable of carrying objects as light as a cigarette butt or as heavy as the roof of a two-story home far out to sea. Masts, rigging, and other material from ships can also become debris if broken off in a heavy storm. Storms or other periods of strong winds or high waves can deposit almost any kind of natural or manmade object into the ocean.

Adding to this problem is the population influx in the coastal zone. More people means more paved area and wastes generated in coastal areas. These factors, combined with the growing demand for manufactured and packaged goods, have led to an increase in non-biodegradable solid wastes in our waterways.

The typical floatable debris from Combined Sewer Overflows includes street litter, sewage (e.g., condoms, tampons, applicators), and medical items (e.g., syringes), resin pellets, and other material that might have washed into the storm drains or from land runoff. These materials or objects can make it unsafe to walk on the beaches, and pathogens or algae's blooms can make it unsafe to swim. Pollutants, such as toxic substances, can make it unsafe to eat the fish caught from the waters. Swimming in or ingesting waters which are contaminated with pathogens can result in human health problems such as sore throat, gastroenteritis, meningitis or even encephalitis. Pathogens can also contaminate shellfish beds.

Impacts of marine debris

Each year, millions of seabirds, sea turtles, fish, and marine mammals become entangled in marine debris or ingest plastics which they have mistaken for food. As many as 30,000 northern fur seals per year get caught in abandoned fishing nets and either drown or suffocate. Whales mistake plastic bags for squid, and birds may mistake plastic pellets for fish eggs. At other times, animals accidentally eat the plastic while feeding on natural food.

The Marine Mammal Commission reports that 267 marine species have been reported entangled in or having ingested marine debris. The plastic constricts the animals' movements, or kills the marine animals through starvation, exhaustion, or infection from deep wounds caused by tightening material. The animals may starve to death, because the plastic clogs their intestines preventing them from obtaining vital nutrients. Toxic substances present in plastics can cause death or reproductive failure in the fish, shellfish, and wildlife that use the habitat.

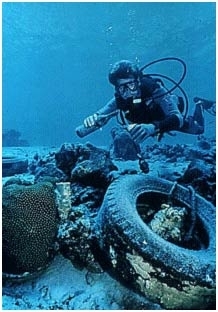

Humans can also be directly affected by marine debris. Swimmers and divers can become entangled in abandoned netting and fishing lines like marine organisms. Beach users can be injured by stepping on broken glass, cans, needles or other litter. Appearance of debris, such as plastic, can also result in economic consequences. Floating debris, either as a floating slick or as dispersed items, is visually unappealing and can result in lost tourism revenues. New Jersey now spends US$ 1,500,000 annually to clean up its beaches, and US$ 40,000 to remove debris from the New York/New Jersey Harbor.

Marine debris also acts as a navigational hazard to fishing and recreational boats by entangling propellers and clogging cooling water intake valves. Repairing boats damaged by marine debris are both time consuming and expensive. Fixing a small dent in a large, slow-moving vessel can take up to 2 days, costing the shipping company US$30,000-40,000 per day in lost carrying fees, as well as up to US$ 100,000 for the repair itself. According to Japanese estimates, the Japanese fishing industry spent US$4.1 billion on boat repairs in 1992. Lost lobster traps cost New England fishing communities US$ 250 million in 1978. These traps continue to catch lobsters and other marine organisms that are never harvested and sold; the communities' economies are therefore adversely affected.

Once debris reaches coastal and ocean bottom, especially in areas with little current, it may continue to cause environmental problems. When plastic film and other debris settle on the bottom, it can suffocate immobile plants and animals, producing areas essentially devoid of life. In areas with some currents, such as coral reefs, debris can wrap around living coral, smothering the animals and breaking up their coraline structures.

Mechanical beach raking, which is accomplished with a tractor and is used to remove debris from the shoreline, can help to remove floatable material from beaches and marine shorelines. However, it can also be harmful to aquatic vegetation, nesting birds, sea turtles, and other types of aquatic life. A study in Maine compared a raked beach and an adjacent natural beach to determine the effects of beach raking on vegetation. Beach raking not only prevents the natural re-vegetation process, but it reduces the integrity of the sand root mat just below the surface that is important in slowing beach erosion. Other problems include disturbance of vegetation if raking is conducted too close to a dune. By removing seaweed, beach erosion can also be caused. Sand compaction is reduced when seaweed is removed, resulting in suspension of the sand in the water during high tides and contributing to loss of sand and erosion of the beach. Beach cleaning machines are harmful to nest birds and can destroy potential nesting sites, crush plover nests and chicks, and remove the plovers' natural wrack-line feeding habitat. To reduce the effects on nesting birds, beach raking should not be done during the nesting season.

Efforts to control marine debris

The Beaches Environmental Assessment and Coastal Health Act (BEACH) of 2000

The Beaches Environmental Assessment and Coastal Health Act (BEACH) was enacted on October 10, 2000, and is designed to reduce the risk of disease to users of the Nation's coastal recreation waters. The act authorizes the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to award program development and implementation grants to eligible states, territories, tribes, and local governments to support microbiological testing and monitoring of coastal recreational waters, including the Great Lakes, that are adjacent to beaches or similar points of access used by the public. BEACH Act grants provide support for developing and implementing programs to notify the public of the potential for exposure to disease-causing microorganisms in coastal recreation waters. The Act also authorizes EPA to provide technical assistance to States and local governments for the assessment and monitoring of floatable materials. In partially fulfilling that obligation, EPA has compiled the most current information to date on assessing and monitoring floatable materials in the document Assessing and Monitoring Floatable Debris.

The International Coastal Cleanup (ICC)

The Ocean Conservancy, formerly known as the Center for Marine Conservation, established and maintains the annual International Coastal Cleanup (ICC) with support from EPA and other stakeholders. The first cleanup was in 1986 in Texas, and the campaign currently involves all of the states and territories of the United States and more than 100 countries around the world. The ICC is the largest volunteer environmental data-gathering effort and associated cleanup of coastal and underwater areas in the world. It takes place every year on the third Saturday in September. In 2001, over 140,000 people across the U.S. participated in the ICC. They removed about 1.6 million kilograms (3.6 million pounds) of debris from more than 7,700 miles of coasts, shorelines, and underwater sites.

National Marine Debris Monitoring Program (NMDMP)

EPA, along with other federal agencies, helped to design the National Marine Debris Monitoring Program (NMDMP), and EPA is supporting The Ocean Conservancy's implementation of the study. NMDMP is designed to gather scientifically valid marine debris data following a rigorous statistical protocol. The NMDMP is designed to identify trends in the amounts of marine debris affecting the U.S. coastline and to determine the main sources of the debris. This scientific study is conducted every 28 days by teams of volunteers at randomly selected study sites along the U.S. coastline. The NMDMP requires, at a maximum, that 180 monitoring sites located along the coast of contiguous U.S. States and Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands be fully operational. The program began in 1996 with the establishment of 40 monitoring sites ranging from the Texas/Mexico border to Port Everglades, Florida and included Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. To date, 163 study sites have been designated and 128 sites are collecting data. The program will run for a 5-year period once all of the study sites have been established.

Further Reading

| Disclaimer: This article contains information that was originally published by the Environmental Protection Agency and NOAA. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth have edited its content and added new information. The use of information from the Environmental Protection Agency and NOAA should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |