Chemical use in Africa: management and responses

Contents

Management challenges

Africa needs to address the threat that existing and increasing chemical use will have on human and environmental health. As the International Conference on Chemicals Management (ICCM) noted: “The sound management of chemicals is essential to achieve sustainable development, including the eradication of poverty and disease, the improvement of human health and the environment and the elevation and maintenance of the standard of living in all countries at all levels of development” (SAICM 2006).

Developing a more effective chemical management system requires addressing the specific challenges Africa faces in management. There is already an extensive global system for chemical management, and it is important not to duplicate efforts but to create synergies and better systems for implementation. Africa faces challenges related to the availability of information and the communication of this to users, inadequate capacity to effectively monitor the use of chemicals, lack of access to cleaner production systems and technologies for waste management, as well as poor capacity to deal with poisoning and contamination. The management of obsolete chemicals, stockpiles and waste presents serious threats to human well-being and the environment in many parts of Africa.

As chemical use and production increases Africa’s chemical management institutions, which already have limited resources and capacity, will be further constrained and overburdened and will not cope. Measures and systems need to be developed to reduce exposure to negative impacts and to reduce human vulnerability.

Management of obsolete pesticides

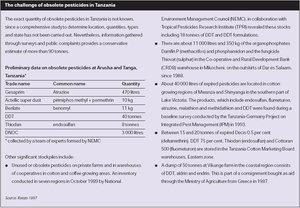

Contaminated sites and obsoletes stocks present serious problems for Africa and require immediate actions. Estimates suggest that across Africa at least 50,000 tonnes of obsolete pesticides have accumulated. Box 1 describes the extent of the problem in Tanzania. These hazardous pesticides are contaminating soil, water, air, and food sources. They pose serious health threats to rural as well as urban populations and contribute to land and water degradation.

Poor people often suffer a disproportionate burden. In poor communities these dangers are compounded by a range of factors including unsafe water supplies, poor working conditions, illiteracy, and lack of political empowerment. Poor communities often live in closer proximity to obsolete pesticide stocks than wealthy people. Children may face heightened exposure and where they do are at higher risk than adults. The WHO estimates that pesticides may cause 20,000 unintentional deaths per year and that nearly three million people may suffer specific and non-specific acute and chronic effects, mostly in developing countries. The risk faced by poor communities is exacerbated by inadequate access to healthcare systems; this is particularly the case for farming communities.

As in other fields of environmental management, partnerships that bring together a range of actors including the private sector, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and governmental organizations can be an effective way of addressing problems. The Africa Stockpiles Programme (ASP) is a global programme supported by the Global Environment Facility (GEF). Prominent partners include the World Bank, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), WWF – the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), the African Union (AU) and the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD). The objective of ASP is to clean up and safely dispose of all obsolete pesticide stocks in Africa and to establish preventive measures to avoid future accumulation so as to protect human and environmental health. Box 2 gives an example of one global initiative that supports Africa’s efforts to reduce its chemical stockpiles.

POPs and PCBs

Although the use of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) is regulated under international law, specifically in the Stockholm Convention, some are exempt from its provisions. In Africa these include dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) and Chlordane. The reasons for these exemptions are multifold, with both cost of alternatives and effectiveness being important considerations. In some cases, such as for DDT and chlordane, the objective is to give the exempted countries the opportunity to find suitable alternatives that are consistent with their social and economic situation before completing phase-out. The lack of public knowledge about possible alternatives is undoubtedly a factor in their continued use.

poly-chlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are mainly used in the manufacture of electrical equipment for electrical insulation. They are used in transformers and capacitors. These are persistent chemicals that do not break down easily and therefore their control and management is a serious challenge for Africa. Management requires undertaking complete inventories, preventing further releases into the environment, managing the stocks and contaminated sites and finally disposal. These challenges are enormous especially if considered within the context of the socioeconomic context of African countries.

Controlling emissions of dioxins (Health effects of chlorinated Dibenzo-p-dioxins (CDDs)) and furans also presents a formidable challenge to African countries because of the potential impact on human health and environment. Technical and operational modifications to the industry and related attitude changes are required.

Responses: policy and institutional arrangements

Recognition of the risks that chemicals pose to the human health and the environment has led to significant progress being made at the international levels to address this. Important recent landmarks include:

- Agenda 21 (1992);

- The World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) (2002);

- The Rotterdam Convention on the Prior Informed Consent (PIC) Procedure for Certain Hazardous Chemicals and Pesticides in International Trade (Rotterdam Convention) (1998) which entered into force in 2004; and

- The Stockholm Convention (2001) which entered into force in 2004.

These multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs) complement the more established global regime that includes:

- International Labour Organization (ILO) conventions dealing with workplace safety (including Convention 170 on Safety in the Use of Chemicals at Work and Convention 174 on the Prevention of Major Industrial Accidents);

- MEAs regulating trade in hazardous waste including Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal, 1989 (Basel) (which entered into force in 1992) and Africa’s Bamako Convention on the Ban of the Import into Africa and the Control of Transboundary Movement and Management of Hazardous Wastes within Africa, 1991(Bamako) (which entered into force in 1998); and

- MEAs dealing with marine pollution.

Chemical management

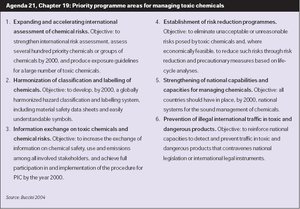

In 1992, the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) focused world attention on concerns related to the risks inherent in chemical production, transportation, distribution, storage, handling and disposal of unused materials and wastes. It adopted Agenda 21 – a global programme of action. Several chapters of Agenda 21 deal directly with the use of chemicals. These focus on environmentally-sound management of toxic chemicals (see Box 3). including the control of illegal international traffic (Chapter 19), the management of hazardous waste (Chapter 20) and capacity-building in developing countries (Chapter 38). This further refined the global approach to environmental problems by emphasising the link between environment and development, the need for integrated responses, and global cooperation and responsibility.

The WSSD reviewed progress made towards achieving the targets set out by Agenda 21. It agreed to ensure that by 2020 chemicals are used and produced in ways that minimize the significant adverse impacts on human health and the environment. It recognized that to achieve this, new management approaches would need to be adopted including the use of transparent, science-based risk assessment and management procedures based on the precautionary approach, as set out in principle 15 of the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development. Genetically modified crops in Africa provides a full overview of science-based risk assessment and how it can be used to support informed decision making. WSSD also committed the global community to support developing countries in enhancing their capacity for the sound management of chemicals and hazardous waste by providing technical and financial assistance – endorsing the UNEP-led Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management (SAICM) in pursuit of these goals.

The Stockholm Convention deals specifically with chemical management and in particular with POPs, PCBs and dioxides. The objective of this convention is to protect human health and environment. Parties are required to take action on an initial group of 12 specified chemicals. This treaty was adopted in May 2001 but, however it only entered into force in May 2004 and it currently has 122 parties including over 30 African countries (Figure 1).

Parties are required, at a minimum, to reduce the total toxic releases from listed chemicals but also to work towards the overall goal of continuing minimization and, where feasible, ultimate elimination. Parties are also required to reduce or eliminate release from stockpiles and waste. They must develop and implement strategies to identify stockpiles and wastes containing POPs and to manage these in an environmentally-sound manner. Further, parties are required to develop national implementation plans (NIPs) within two years of entry into force of the Convention.

Within Africa there have been several important responses to improving chemical management. At a regional meeting in Abuja, Nigeria, in May 2004, African governments committed themselves to promote synergies and coordination among chemical regulatory instruments and agencies, and specifically proposed the following activities, (SAICM 2004):

- Manage chemicals at all stages of their life cycle, using the principles of “cradle-to-grave” life cycle management.

- Target the most toxic and hazardous chemicals as a priority.

- Ensure full integration of chemicals management and better coordination among stakeholders.

- Increase chemical safety capacity at all levels.

- Ensure that children and other vulnerable people are protected from the risks of chemicals. Promote corporate social responsibility and develop approaches that reduce human and environmental risks for all, rather than

- transferring the risks to those least able to cope with them.

- Incorporate the legal approaches or principles of precaution, polluter pays, and the right-to-know. This must be complemented by a commitment to substitution of toxic chemicals by less harmful alternatives and promote more environmentally-friendly practices by industries. This can be achieved through, among other measures, encouraging the private sector to seek compliance with the International Organzation for Standardization (ISO) 14000 standards.

- Integrate the precautionary, life cycle, partnership, liability and accountability approaches in management.

The NEPAD Environmental Action Plan (NEPAD-EAP) sets an Africa-wide approach to environmental management. Although chemical management is not one of the programme areas, it is identified as a key crosscutting issue. At the national and regional level, environmental action programmes will need to respond to the challenges of chemical management. Some of the actions that could be included are emergency response plans, prevention of illegal transboundary movement of chemicals, capacitybuilding of regional centres for the management of dangerous waste in the context of the Stockholm Convention, and the development and implementation of programmes for reducing hazardous waste.

International trade

The impacts of trade in chemicals on environmental sustainability and human well-being and development are key motivations for law development in this area. However, as the global trade regime strengthens it is uncertain whether such initiatives will come under threat from powerful trading blocs.

The Rotterdam Convention was adopted in 1998 in response to gaps within international law related to trade in hazardous chemicals. The Rotterdam Convention has 106 parties – including 37 African countries – and entered into force in 2004. The rapid growth in chemical production and trade during the last three decades and the associated risks posed by hazardous chemicals and pesticides was an important motivation. It was evident that many countries lacked the institutional and infrastructural framework to effectively monitor import and use of such substances. The Convention seeks to promote shared responsibility and cooperative efforts in such international trade in order to:

- Protect human health and the environment from potential harm; and

- Contribute to their environmentally-sound use of chemicals by facilitating information exchange about their characteristics, providing for a national decision-making process on their import and export.

Two other treaties deal specific with the problem of the transboundary movement and disposal of hazardous waste. Africa’s Bamako Convention was adopted by the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in 1991 because the approach of the global Basel Convention was seen as not sufficiently strong to protect Africa from the threat of hazardous waste dumping. The Convention has 29 signatories, 21 of which have ratified it, and entered into force in 1998. However, many more African countries are party to the more tradefriendly Basel Convention.

The Basel Convention has 168 parties, of which 46 are Africa countries; it entered into force in 1992. The focus of this convention is to control the movement of hazardous waste, taking into account social, technology and economic aspects, to ensure the environmentally-sound management and disposal and to prevent illegal waste traffic. It recognizes the importance of the reducing hazardous waste generation, the centrality of information for effective management and the obligation to inform the importing country in advance. In 2001, the Conference of the Parties undertook to enhance capacity in Africa to deal with problems associated with stockpiles (see Box 2).

African has three Basel Convention Training Centres. These centres were established under the Secretariat of the Basel Convention with the specific objective of enhancing capacity-building. However, in recent years their mandates have expanded to include other activities related to the Rotterdam and Stockholm Conventions. The centres will support countries to synergize their chemical management-related activities at national level.

New Partnerships: a strategic approach to international chemicals management

At a global level, there has been long-standing cooperation in the management of potentially harmful chemicals. Development of legislation often focuses on a specific problem that needs to be remedied – this can result in a poorly harmonized approach that fails to create a holistic framework for tackling the depth and breadth of the issue. The development of treaties for chemical management faces precisely this problem.

There has been a steady increase in global support for the development of an approach to chemicals that takes into account issues of human well-being, environmental sustainability and development and that provides a comprehensive managerial framework. Since 2003, international organizations, governments and other stakeholders have come together in a UNEPled initiative, SAICM. This initiative seeks to promote synergies and coordination among regulatory instruments and agencies; it includes an overarching strategy, a global plan of action and a high level declaration. The initiative was endorsed by the WSSD in Johannesburg in 2002. SAICM’s policy strategy establishes objectives related to risk reduction, knowledge and information, governance, capacity-building and technical cooperation and illegal international traffic, as well as underlying principles and financial and institutional arrangements. To this end it has adopted a Global Plan of Action, which sets out proposed “work areas and activities” for implementation of the Strategic Approach.

National legislation

Environmental law has been strengthened across Africa since UNCED. Environmental rights approaches have been developed in many African countries, including Benin, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Ghana, Malawi, Mozambique, the Seychelles and Uganda. Such approaches create a sound basis for dealing with the problems posed by chemicals, protecting human health and a safe environment, while promoting sustainable development.

The development of national legal instruments to implement a comprehensive approach to chemicals, however, has lagged behind. This is exacerbated by shortages of resource allocation for enforcement, monitoring, and training. Effective legislation will require the monitoring as well as the establishment of proper management and disposal systems. Establishing such systems and obtaining the requisite equipment is expensive. Opportunities to bring chemical producers in as part of a solution may be difficult. While it is important for legislation to create proper liability and cost-recovery measures, through, for example, the incorporation of the polluter pays principle, it is also important to look at possible incentives. Public knowledge and information about chemicals and their impacts, underlies the choices of consumers and, should be promoted. Consumer and shareholder values, interests and concerns can be an important shaper of corporate policy.

Technology and capacity issues will also need to be addressed in the implementation of legislation. For example, the development of environmentally acceptable disposal facilities requires a delicate balance between technology complexity and applicability. The requirement of the Stockholm Convention, that the parties develop NIPs, provides unique opportunities for countries to reassess their strengths and weakness in the area of chemical management at national level with global support.

Institutional arrangements for the sound management of chemicals

Institutional arrangements for the sound management of chemicals in African vary from one country to another. In many countries responsibility lies with several agencies. For example, Zimbabwe has four different ministries that administer chemical-related environmental laws, Botswana also has four ministries, while in South Africa responsibility is shared among departments for environment and tourism, agriculture and the provincial governments.

During the 1990s, most African countries established a wide variety of new institutional arrangements for environmental management, protection and restoration. For example, many countries in Northern and Southern Africa created new environment ministries while most Eastern African countries favoured separate environmental protection agencies, as in Uganda and Kenya. Western and Central Africa have a mixture of both. However, the absence of coordination seriously undermines the formulation of a strategic approach and the translation of treaties related to chemical management into country programmes. When sectoral approaches dominate, the mechanisms for cooperation and coordination among different agencies are often ineffective.

Most countries face problems of access to adequate financial resources. Environmental ministries often have smaller budgets and weaker political voices than, for example, those that directly manage productive natural resources such as agriculture or determine economic policy. The result has been uncertainty and a reduced ability to plan and carry out core activities. Effective budgets for agencies have also shrunk. Competing for scarce funds and political commitment, existing institutions are frequently torn between competing priorities. The provision of budgets that cover the operations of institutions will remove some of the bottlenecks experienced. However, there is a need to identify new and additional sources for financial assistance. New financial resources are needed to undertake the programmes related to:

- Ensuring the protection of children and other vulnerable populations from the risks posed by chemicals, while increasing chemical safety at all levels.

- Promoting corporate social responsibility through the development of approaches that reduce human and environmental risks for all and do not simply transfer risks to those least able to address them.

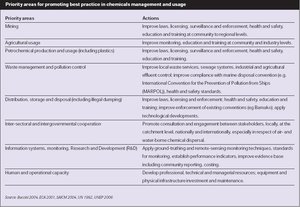

- Promoting best practices in the manufacture, distribution, trade, use and disposal of chemicals and products required to meet sustainable development objectives.

- Reducing the risks posed by chemicals to human health and the environment, with a focus on measurable indicators.

- Updating and bringing laws in line with current scientific knowledge.

- Clarifying and harmonizing responsibilities of different ministries.

- Identifying and filling in gaps in the legal framework for environmental protection.

In order to promote the sound management of chemicals in Africa, it is essential that appropriate institutional, policy, legal and administrative arrangements are in place in all countries in the region. Although institutional arrangements for chemical management will vary from country to country due to different socioeconomic conditions, there are some essential elements for the sound management of chemicals that should be included.

An effective legal and policy framework for the management and control of chemicals should be multisectoral with the ability to promote a coherent and coordinated approach. This requires:

- Information gathering and dissemination systems;

- Risk analysis and assessment systems;

- Risk management policies;

- Implementation, monitoring and enforcement mechanisms;

- Effective management of wastes at source;

- Rehabilitation measures for contaminated sites and poisoned persons;

- Effective education and information communication programmes;

- Labelling requirements that support sound use and consumer choice;

- Emergencies and disaster responses;

- Liability and responsibility rules; and

- Environmental impact assessments and social impact assessments.

This could be supported through

- Multi-stakeholder participation;

- Rights of access to information;

- Application of the precautionary approach or principle;

- Cost-benefit analysis; and

- Adoption of the polluter pays principle (PPP).

Further reading

- ASP, 2003. Obsolete Pesticide Stocks: An Issue of Poverty. Africa Stockpiles Programme.

- AU, 2005. List of countries which have signed, ratified/acceded to the Bamako Convention on the Ban of the Import into Africa and the Control of Transboundary Movement and Management of Hazardous Wastes within Africa. African Union, Addis Ababa.

- Buccini, J., 2004. Global Pursuit of the Sound Management of Chemicals. World Bank,Washington, D.C.

- NEPAD, 2003. Action Plan for the Environment Initiative. New Partnership for Africa’s Development, Midrand.

- SAICM, 2004. of the African Regional Meeting on the Development of a Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management. Abuja, Nigeria, 26-28 May. SAICM/AfRM/1. Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management.

- SAICM, 2006. Draft high-level declaration, International Conference on Chemicals Management, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 4-6 February. SAICM/ICCM.1/2. Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management.

- Secretariat of the Basel Convention, 2005. Parties to the Basel Convention.

- Secretariat of the Rotterdam Convention, 2006. Signatures and Ratifications.

- UN, 1992a. Agenda 21. Proceedings of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3-14 June. United Nations.

- UN, 1992b. Rio Declaration on Environment and Development. In Report of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3-14 June.A/CONF.151/26 (Vol. I. Annex 1).

- UNEP, 2005. GEO Yearbook 2004/5: An Overview of Our Changing Environment. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi.

- UNEP, 2006. Africa Environment Outlook 2.

|

|

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |