Regional cooperation for peace and sustainable development in Africa

| Topics: |

“Safeguarding the environment is a crosscutting United Nations’ activity. It is a guiding principle of all our work in support of sustainable development. It is an essential component of poverty eradication and one of the foundations of peace and security.” ~ Kofi Annan, United Nations Secretary-General, 1997

Contents

Introduction

Peace is a prerequisite for human development and effective environmental management, both of which are critical to Africa achieving national and regional goals, such as those of the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) and its environmental action plan (NEPAD-EAP), as well as globally agreed objectives, including those of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (Regional cooperation for peace and sustainable development in Africa) . The New Partnership for Africa’s Development, which focuses on promoting economic development with a view to eradicating poverty and placing countries – individually and collectively – on a path of sustainable growth and development, recognizes the importance of peace:“The three pillars of sustainable development, however, cannot be achieved without peace and security on the continent” (NEPAD 2003a).and

“We are determined to increase our efforts in restoring stability, peace and security in the African continent. These are essential conditions for sustainable development, alongside democracy, good governance, human rights, social development, and the protection of the environment and sound economic management”(NEPAD 2002).

Cooperation at different levels – from local to national, to sub-regional, to regional, and to international – and peace represent the key to unlock many opportunities for sustainable development.

Conflict can only continue to exacerbate the problems faced in the region, as it impacts directly on economic potential and human well-being, shattering the very foundations of society. The data and information on the impacts of conflict in Africa are staggering: since 1970, more than 30 wars have been fought in Africa, seriously undermining regional efforts to ensure long-term stability, prosperity and peace. More than 350 million people in Africa live in countries that are affected by conflict. This has multiple implications for the real opportunities available to people, and it undercuts their capability to lead lives that they value. There is a strong negative correlation between conflict and human development: in 2005 most of the countries with the lowest Human Development Index (HDI) rankings were also those immersed in conflict or had recently emerged from it. The resources available to people are diminished – for example, through the loss of access to land and other natural resources on which livelihoods are based, and the loss of access to education and health care – and so is their freedom to choose. Severe military conflict in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is reported to cut life expectancy by four to six years and to contribute to a rise in infant mortality. Conflict increases the threat of bodily harm, and destroys the social and political networks on which social cohesion is based, consequently increasing the incidence of social exclusion. Women and girls face the risk of rape and kidnapping; in many of Africa’s conflicts this assault on women has been used as a weapon. In Rwanda, for example at least 250,000 women were raped during the 1994 genocide, and many were deliberately infected with HIV/AIDS; 17 percent of internally displaced women and girls surveyed in Sierra Leone had experienced sexual violence – both war- and non-war-related – including rape, torture and sexual slavery. During South Africa’s anti-apartheid struggle, the systematic physical abuse of women prisoners was an important aspect of that conflict. Recognizing the importance of gender in conflict, in 2000 the United Nations (UN) Security Council adopted Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security.

By the end of 2003, more than half of the total 24 million internally displaced people (IDP) worldwide were found in 20 African states (Norwegian Refugee Council 2004). In 2004, there were almost 2.9 million officially registered refugees in Africa, and many more people living outside of their country of origin without legal protection. By 2005, this number had risen to 4.9 million. Refugees and IDPs are amongst the most vulnerable people.

Armed conflict is a major expense, resulting in the diversion of essential resources from human and economic development. For example, the diversion of resources to finance war in Central Africa was about US$1,000 million annually, and more than US$800 million in Western Africa. Refugee assistance is an additional cost and has been estimated at more than US$500 million for Central Africa alone. For Africa, therefore, there can be no alternative to peace and regional cooperation, and the environment is a key factor. Principle 25 of the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development emphasizes (UN 1992):

“Peace, development and environmental protection are interdependent and indivisible.”

However, the issue of peace is much broader than simply armed conflict. The report of the UN High-level Panel on Threats, Challenges and Change – A More Secure World: Our Shared Responsibility – states:

“… we know all too well that the biggest security threats we face now, and in the decades ahead, go far beyond states waging aggressive war. They extend to poverty, infectious disease and environmental degradation …” (UN 2004).

Africa has made considerable progress towards building peace. In 1998, there were 14 countries who were in engaged in armed conflict or civil strife; by August 2005, the UN Secretary-General reported that only 3 countries were engaged in major conflict although many more countries were involved in civil strife of a lower intensity (UN General Assembly 2005). Most countries have greatly improved their governance systems, yet for many a combination of historical, external and internal factors continue to contribute to conflict.

Regional cooperation for sustainable development

Africa has a long history of regional cooperation, with many sub-regional and regional institutions and frameworks established and maintained long before the 20-year period of this environmental assessment report. While most of them focus on political and economic issues, others are concerned with the sharing and management of natural resources. In particular these include multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs), river basin commissions (RBC), and institutions concerned with biodiversity conservation and the utilization of transboundary resources.

From the United Nations Charter and the Constitutive Act of the African Union (AU) on one hand, to the subregional economic groups such as the Economic Commission for West African States (ECOWAS) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) on the other, the region has many mandates and institutions which promote – directly and indirectly – peace and conflict resolution. The negotiation and adoption of regional and sub-regional MEAs and protocols, over the last 20 years, has facilitated the establishment of a more reliable body of laws and institutions to respond to the needs of Africa in a globalized world. Revitalized RBCs, some dating back to the colonial period, recently established transboundary national parks, and many other governance structures provide the foundation upon which the region is taking a more assertive role in resolving and avoiding conflict, and building opportunities for development.

The African Union

In 1999, the Organization of African Unity (OAU) embarked on the process of establishing the African Union (AU) – which was launched in 2002. The AU’s objective is to accelerating the process of regional integration to enable Africa to play its rightful role in the global economy while addressing multifaceted social, economic and political problems, compounded as they are by certain negative aspects of globalization. The AU is Africa’s principal organization for the promotion of accelerated socioeconomic integration.

The AU builds on the long history of collaboration established by the OAU. The many achievements of the OAU include the adoption of the Lagos Plan of Action (1980) and the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights (1981). In the 1990s, the OAU committed to place the African citizen at the centre of development and decision making and the AU has continued to adopt measures to support this. In 1993 the OAU adopted the Mechanism for Conflict Prevention, Management and Resolution – a practical expression of the determination to find solutions to conflicts, and to promote peace, security and stability. In 2000 this was complemented by the adoption of the Solemn Declaration on the Conference on Security, Stability, Development and Cooperation which establishes fundamental principles for the promotion of democracy and good governance.

Building on this history, the AU strives to build a partnership between governments and all segments of civil society, in particular women, youth and the private sector, in order to strengthen solidarity and cohesion amongst the peoples of Africa. A key focus is on the promotion of peace, security and stability as a prerequisite for the implementation of the development and integration agenda of the Union. Its organs include a Peace and Security Council, the Pan-African Parliament, and specialized technical committees. The AU’s Constitutive Act (Box 1) is the compass by which member states should avoid the pitfalls of conflict and it provides the road signs they should follow to ensure sustainable development.

The United Nations

(Source: N. Behring/UNHCR)

All 53 countries in Africa are members of the UN. The UN Charter emphasizes a global vision of peace as the basis for development, with a special focus placed on “fundamental human rights, the dignity and worth of the people, equal rights of men and women, and of nations large and small” (UN 1945). To this end, two essential purposes of the UN are:

- To maintain international peace and security, and to that end to take effective collective measures for the prevention and removal of threats to peace and the suppression of acts of aggression or other breaches of the peace. Collectively, countries agree to bring about by peaceful means, and in conformity with the principles of justice and international law, the settlement of international disputes or situations which might lead to a breach of the peace.

- To achieve international cooperation in solving international problems of an economic, social, cultural, or humanitarian character, and to promote and encourage respect for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language or religion.

For the UN, environment is an important aspect of its peace-building goals:

“Safeguarding the environment is a crosscutting United Nations activity. It is a guiding principle of all our work in support of sustainable development. It is an essential component of poverty eradication and one of the foundations of peace and security” (Annan 1997).

The UN has, over decades, organized various international conferences in which Africa has participated, that focus on strengthening cooperation in sustainable development efforts. For example, the 1992 UN Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), also known as the Earth Summit, adopted Agenda 21 – a blueprint for sustainable development which emphases the value of cooperation. A decade later, the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD), held in Johannesburg in 2002, further emphasized the centrality of peace and security in Africa to achieving environmental goals. Chapter 8 of the WSSD Johannesburg Plan of Implementation, which focuses on Africa calls on the global community to:

“Create an enabling environment at the regional, sub-regional, national and local levels in order to achieve sustained economic growth and sustainable development and support African efforts for peace, stability and security, the resolution and prevention of conflicts, democracy, good governance, respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms, including the right to development and gender equality” (UN 2002).

Regional fora on environment and development

Regional processes, such as the African Ministerial Conference on the Environment (AMCEN) and African Ministerial Council on Water (AMCOW) provide leadership on environment and freshwater. AMCEN has been in existence since 1985, while AMCOW was launched in 2002. Both mobilize political and technical support to address diverse environmental issues, such as land degradation and desertification, chemicals management, access to safe water and sanitation, and integrated water resource management (IWRM).

From the outset, AMCEN has sought to strengthen cooperation in environmental policy responses in the region. In its inaugural declaration adopted at the end of the 1985 meeting in Cairo, AMCEN highlighted its major objective as strengthening cooperation between African governments in economic, technical and scientific activities, with the prime objective of halting and reversing the degradation of the African environment in order to satisfy food and energy needs.

African ministers have also pursued cooperative initiatives on critical environmental issues, such as energy use, the phase-out of lead fuel, and chemicals. They have also adopted an agricultural initiatves (Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme) to boost food production and help the region attain food self-sufficiency (see Land resources in Africa). Through the NEPAD process, African governments have also produced a health strategy, which among other issues, recognizes the centrality of health to development, and that poverty cannot be eradicated – or substantially alleviated – as long as disease, disability and early mortality continue to burden Africa’s people. For example, malaria has slowed annual economic growth by 1.3 percent, imposing a loss of US$12,000 million on the region per year.

Africa has adopted a number of MEAs that address regional concerns. These include the Convention on the Ban of the Import into Africa and the Control of Transboundary Movement and Management of Hazardous Wastes within Africa (Bamako)(see Chemical use in Africa) and the 2003 African Convention on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (ACCNNR) (see Human dimension of development in Africa and Interlinkages: environment and policy web in Africa). Although implementation of both remains a challenge due primarily to the lack of resources, these two conventions show the spectrum of regional cooperation in environmental issues. These are complemented, as discussed below by various subregional agreements and initiatives.

The launch in October 1999 of the African Renaissance Institute played an important role in developing a framework for enhancing cooperation. South Africa’s President Thabo Mbeki, who launched the Institute, encouraged the mobilization of all African countries, including their people and organizations, to promote the objectives of an African Renaissance – the rebirth and renewal of the region (Box 2).

Regional Economic Communities

There are a number of regional economic communities (RECs) in Africa. These include, among others, the:

- Community of Sahel-Saharan States (CEN-SAD);

- Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS);

- Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA):

- Intergovernmental Authority for Development (IGAD):

- Southern African Development Community (SADC);

- Arab Maghreb Union (UMA); and

- Economic Commission of West African States (ECOWAS).

All of these RECs are actively engaged in promoting cooperation, although primarily with a focus on economic development. Principles and motivations underlying their formation generally include sovereign equality; solidarity, peace and security; human rights, democracy and the rule of law; equity, mutual benefit; and the peaceful settlement of disputes. Several have embarked on extensive environmental collaboration.

At the sub-regional level, the SADC Treaty recognizes peace and security provisions, alongside cooperation in natural resource management (NRM), as essential to meeting its objective of achieving sustainable utilization of natural resources and effective protection of the environment (SADC 1992). In support of this, various protocols that establish shared institutions have been adopted, these include:

- The Protocol on Shared Watercourse Systems, which was signed in 1995 by the member countries and amended in 2000 to harmonize it with the most important aspects of the 1997 UN Convention on the Law of Non-Navigational Uses of International Water Courses.

- The Protocol on Energy, 1996.

- The Protocol on Transport, Communications and Meteorology, 1996.

- The Protocol on Wildlife Conservation and Law Enforcement, 1999.

Another example of cooperation in SADC is the establishment, in 2004, of the Zambezi Basin Commission after more than two decades of on-and-off negotiations among the eight riparian states.

A number of other recent initiatives at the subregional level hold promise for enhanced regional cooperation in a number of different areas, including the environment. In Eastern Africa, for example, the revival of the East African Community (EAC) in 1999 is intended to widen and deepen cooperation among the member states – Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda – in many areas, including environmental management (Box 3). In the Great Lakes Region (GLR), where conflict has been an obstacle to regional cooperation, the link between environmental quality, and peace and security has been articulated by policymakers. Meeting in Nairobi in September 2004 for the UN Great Lakes initiative, stakeholders from seven countries proposed principles and actions critical to addressing suspicion and conflict, and for encouraging cooperation among the member states. The principles focus on peace and security, democracy and good governance, economic development and regional integration, and humanitarian and social issues.The following actions and principles were seen as essential for development in the GLR (UNEP 2004b):

- Environmental quality and sustainable NRM are a precondition for peace and security in the GLR. Peace and security are a precondition for good environmental quality and sustainable resource management. Given this close relationship between peace and environment, it was emphasized that management plans should include provisions which encourage equitable access to and sharing of benefits from natural resource use, so as to avoid competition for natural resource control. These plans should also identify and support opportunities through which environmental management can contribute to peace and peaceful coexistence.

- Political commitment to the tenets of democracy and good governance are critical for the sustainable management of environmental resources. This includes strengthening national capacities, and fostering regional cooperation through the development of sustainable NRM programmes. Such programmes should focus on strategic transboundary resources such as lakes, river basins, mountain ecosystems, protected areas, and unique cultural, biodiversity and historical sites.

- Environmental management and protection should be an integral part of economic development and regional integration for sustainable development. This includes the use of sustainable transboundary natural resource management (TBNRM) as an opportunity for regional economic development and integration.

- Armed conflicts result in diverse humanitarian and social situations that have environmental implications, such as increased environmental degradation. This, in turn, leads to – or exacerbates – poverty which, in turn, further increases environmental degradation through unplanned development of human settlements and the overharvesting of resources. Effective responses include considering environmental sustainability in decisions related to the location and establishment of refugee camps, to avoid increasing stress on already fragile environments, and encouraging cooperation between the host and refugee populations, especially on the use of natural resources, by taking into account the needs of the host community.

Cooperation in freshwater resources management

River basin agreements

(Source: L. Schadomsky/Still Pictures)

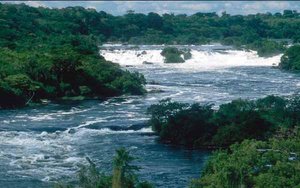

With over 50 significant international river basins, Africa has the second largest number of such basins in the world, providing opportunities for regional cooperation and transboundary management of the resource. River basin institutions have been established to jointly manage water resources, and some of these institutions date back to the colonial period. For example, Africa’s largest river, the Congo – which is over 4,000 km long – had its first treaty adopted in February 1885 as part of the Berlin Conference.

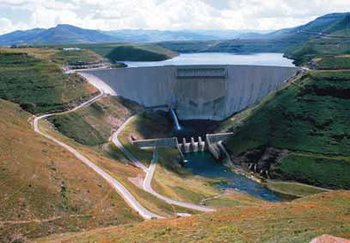

Some rivers have more than one treaty governing water resources management. For example, the Senqu/Orange basin which includes South Africa, Namibia, Botswana and Lesotho has at least five agreements, four of which relate to the Lesotho Highlands Water Project. This project is possibly Africa’s most significant water export-import activity between countries. The agreements between Lesotho and South Africa treat water as a commodity, from which the former earns revenue in foreign currency and the latter imports a much needed resource for human consumption and industrial operations, mostly in the Gauteng Province. This province generates about 60 percent of South Africa’s industrial output and 80 percent of its mining output, and is home to more than 40 percent of the country’s population. The project also generates hydropower for Lesotho. The Lesotho Highlands Water Project, which started in 1984, will cost about US$8,000 million by the time it is completed in 2020. Despite the successes at a bilateral level, a shortcoming is that it has not included all basin states and therefore may affect the rights and interests of other states, for example, water availability in Namibia and the Orange River estuary. The project has also placed new pressures on local riparian people, undercutting human well-being by directly threatening food security and agriculture-derived income. In particular, there have been problems with resettlement and the restoration of livelihoods of those whose lands were submerged due to dam construction. Local people displaced by the dam have not enjoyed the benefits of this project – hydropower. None of the ten villages promised connection have yet been connected to the electrical grid. These impacts on human well-being could increase the potential for conflict at the local and national level. These lessons demonstrate the need for collaborative approaches that take account of all interests including those of states and communities.

Many other initiatives exist related to water resources management in the region. Some have more challenges than others. Perhaps two of the most visible, often pitting environmentalists against developers or spawning national security fears, are the Okavango and the Nile basins. The strategic importance of water – including for food security, energy generation, and transport among other uses – has caused some to speculate about the possibility of conflict over watercourses in Africa and elsewhere. However, through a variety of technological, policy and institutional innovations, water management in Africa also has the potential to act as a source of cooperation and mutual benefit between communities and nations.

Okavango delta – a challenge for sub-regional cooperation

The Okavango basin is a good example of a situation which holds promise, as well as many challenges. The Okavango River rises in the highlands of Angola (where it is known as the Cubango River) and crosses into north-eastern Namibia’s Caprivi Strip before flowing into Botswana. The Okavango River is the only exploitable perennial river in Botswana and Namibia, which are extremely arid countries. The delta, which is in the middle of the Kgalagadi (Kalahari) Desert, is a highly significant area of biodiversity. The basin, which is relatively undeveloped, partly as a result of about three decades of conflict in Angola and also because of the international importance of the flora and fauna in the Delta, has gained the attention of many major environmental conservation organizations. Significantly, two of the three riparian countries are also among the most economically active in Southern Africa.

The peace now prevailing in Angola provides opportunities for development in the remote and marginalized watershed areas. But unregulated increased industrialization could result in increased pollution and increased abstraction of water from the Okavango River. The increasing demands potentially pit one state against the other. The SADC Protocol on Shared Watercourse Systems (referred to above) has proved to be a very useful tool for collaborating and resolving these kinds of concerns. Information on hydrological phenomena and the wider environmental context is crucial for effective management and reconciling differences. Often the different priorities pursued by different users (whether at the community or state level) are justified by contrasting narratives and competing sets of “expert discourses”. One important way of finding solutions and moving beyond disagreements is to develop a set of data on water-flows and other basic indicators that all riparian countries agree on.

Nile Basin Initiative

(Source: IRN)

Through information sharing, capacity-building, and joint projects, it is possible to create “transnational communities” of scientists, civil society organizations, and other stakeholders. The Nile Basin Initiative (NBI) is an example of a high-level forum that has combined aspects of “high politics” with technical cooperation and information sharing. This is, in part, is intended to foster trust and build confidence of the riparian countries in each other. The vision of the NBI is “to achieve sustainable socioeconomic development through the equitable utilization of, and benefit from, the common Nile Basin water resources.”

The NBI has emerged from several decades of cooperative work between the riparian states, initially based around scientific information sharing. Such projects include the Hydrometeorological Survey of the Catchment of Lakes Victoria, Kyoga and Albert (HYDROMET) (1967-1992), funded by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the Technical Cooperation Committee for the Promotion of the Development and Environmental Protection of the Nile Basin (TECCONILE) which was founded in 1993, and a series of ten “Nile 2000” conferences which were funded by the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA).

The objective of TECCONILE was to enable sustainable development of Nile waters through basinwide cooperation and equitable use of water. This has been described as a “revolutionary” initiative since it was the first to bring together all riparian states for the stated aim of equitable use of the Nile (Kivugo 1998). To this end, donors have assisted member states in developing national water master plans and integrating these into a Nile Basin Development Action Plan. They also supported activities to build capacity for IWRM. While TECCONILE was successful at many levels, some downstream riparian states did not participate fully.

In 1997, the Council of Ministers of Water Affairs of the Nile Basin States (Nile-COM) requested the World Bank to coordinate and lead donor activities, and since then from that time CIDA, UNDP and the Bank have worked in concert. In early 1999, the NBI was launched, as another “transitional institutional mechanism” for riparian cooperation.

The highest decision-making body of the NBI is Nile-COM which encourages the active participation of all states through among other measures, a rotational one-year chair. Technical support is provided by the Nile Technical Advisory Committee (Nile-TAC), with one member (backed up by one alternative member) from each state. The NBI Secretariat (Nile-SEC) is the implementation arm, directed by the former Director of the Water Resources Department of Tanzania. The objectives of the Nile River Basin Strategic Action Programme are to (Nile-COM 1999):

- Develop the water resources of the Nile basin in a sustainable and equitable way to ensure prosperity, security and peace for all its peoples;

- Ensure efficient water management and the optimal use of water resources;

- Ensure cooperation and joint action between the riparian countries;

- Seek win-win solutions;

- Target poverty eradication and promote economic integration; and

- Ensure that the programme results in a move from planning to action.

Under the NBI, the 1929 Nile Waters Agreement is being renegotiated. One of the key aspects of this process is the finalization of the Nile Basin Cooperative Framework (project D3 of TECCONILE) which lays out the ground rules for legal and institutional arrangements. The finalization of the draft framework, by a panel of experts from each country as well as a negotiation committee, is under way.

Cooperation in wildlife and biodiversity management

(Source: Howes/UNEP/Still Pictures)

Africa has a long history of cooperation in wildlife management, dating back to old agreements, such as the 1933 London Convention Relative to the Preservation of Fauna and Flora in Their Natural State. The management of wildlife has evolved since then – from preservation to sustainable utilization. More recently, some countries have adopted a transboundary approach to wildlife management, establishing TBNRM areas. Southern Africa has been a major player, in redefining and shifting the conservation agenda, as well as a pioneer in the development of TBNRM. It has adopted and implemented a wide range of such initiatives, from those that establish transboundary parks, to mountain conservation areas, to integrated management frameworks for shared marine ecosystems, to spatial development initiatives.

Ai-Ais/Richtersveld Transfrontier Park

The Ai-Ais/Richtersveld Transfrontier Park is a new transboundary park between South Africa and Namibia, which was proclaimed in 2003. It has been described as a collection of “jigsaw pieces” to eventually create one of the world’s greatest coastal sanctuaries to protect a unique desert ecosystem across three countries, covering about 180,000 km2.

It is intended to eventually include Angola. Namibia has signed a memorandum of understanding with Angola to pursue the establishment of a similar transfrontier park across the Kunene River. The three countries expect to establish by 2006 a super park – which would be about the same size as Uruguay – bringing these various areas together. Encompassing an arid landscape, the “super park” will be long and thin, stretching for about 2,400 km along Southern Africa’s Atlantic seaboard, and crossing the boundaries of South Africa, Namibia and Angola. The first step to the realization of this super park is the treaty between South Africa and Namibia to establish the Ai-Ais/Richtersveld Transfrontier Park, which spans the Orange River boundary to link South Africa’s Richtersveld with Namibia’s Ai-Ais and Fish River Canyon National Park.

Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park

(Source: B. Belcher/CIFOR)

The 35,000 km2 Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park connects South Africa’s Kruger National Park, Mozambique’s Limpopo National Park, and Zimbabwe’s Gonarezhou National Park, and is seen as an integral part of the Maputo Development Corridor. This megapark, which will be more than three times the size of Yellowstone National Park in the United States and almost as big as The Netherlands, will be one of the biggest conservation areas in the world.

The Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park is a huge ecosystem that is home to a wide variety of wildlife, including those most sought after by tourists – Panthera leo (lion), Ceratotherium simum (white rhinoceros), Diceros bicornis (black rhinoceros), Giraffa camelopardalis (giraffe), Loxodonta africana (elephant), Hippopotamus amphibius (hippopotamus) and Syncerus caffer (buffalo). It will also help strengthen economic relations between the three Southern African neighbours by attracting greater numbers of tourists: “creating new jobs and fortifying a tourism base not yet meeting its full potential”. The park will allow managers from the three different parks to consolidate their infrastructure development, law enforcement, and fire management strategies and thus effectively lower costs. It also addresses the most serious worldwide threat to wildlife: the loss and fragmentation of habitat.

Congo Basin Forest Partnership

(Source: E. Dounias/CIFOR)

Central African countries have taken the lead in trying to effectively manage the sub-region’s forest resources. A recent example is the meeting of the Conference of Ministers for the Forests of Central Africa (COMIFAC) in Yaoundé, Cameroon, in January 2003. It highlighted the fact that African tropical forests constitute significant natural wealth for present and future generations. They urged the new partnership to:

- Be well-balanced, responsible, transparent and to promote agreement among the parties;

- Reconcile conservation objectives with development requirements;

- Ensure the conservation of the Congo basin forests through implementation of the Plan de Convergence priority actions;

- Help reduce poverty in Central Africa through greater involvement of communities and local nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in conserving ecosystems;

- Strengthen and develop national capacities; and

- Include all international organizations that are willing to participate in efforts for sustainable management of the Congo basin forests.

Given the global significance of the Congo basin forest – it is the second largest forest in the world after the Amazon, and plays an important role in climate regulation, as well as being a huge repository of biological diversity – the countries of the Congo basin appealed for broad international solidarity to execute the UN Resolution No 54/214 of December 22, 1999, and support their effort for conservation and sustainable management of these forest ecosystems. The partnership has been supported by the second Summit of Head of States of Central Africa on the Conservation and Sustainable Management of the Forest Ecosystems, held in Brazzaville in February 2005. The Central African leaders adopted a declaration and an agreement, which commits the parties to:

- Recognize, as a national priority, the conservation and sustainable management of forests as well as the protection of their environment.

- Accelerate the establishment of the necessary instruments for sustainable development, particularly internationally accepted certification systems and to build the requisite capacity for their implementation.

- Put in place measures aimed at incorporating conservation and sustainable management of ecosystems into other development sectors including transport and agriculture.

- Establish in every country, sustainable financial mechanisms for the funding of the forest sector.

- Speed up the creation of transboundary protected areas between Central African countries.

- Strengthen participatory mechanisms aimed at increasing the consultation and participation of rural populations in the planning and management of forests.

- Develop the partnership with the international community to attract the necessary funds to finance these activities.

To facilitate the implementation of the agreement and promote the harmonization and monitoring of forest policies in Central Africa, the nine countries of Cameroon, Central African Republic (CAR), Congo Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Equatorial Guinea, Chad, Burundi, Rwanda and São Tomé and Príncipe, established COMIFAC.

Conclusion

Africa is both rich in human and natural resources, yet the poorest region the world, often depending on food aid and imports to supplement the needs of its food insecure population. There are many factors which influence underdevelopment in the region, many external but many others which are internal, including war.

A crisis of governance – weak political processes and institutions, weak legal systems, poor economic performance and debt, and underdevelopment and poverty – contributes to undermining the well-intentioned institutions and measures that have been established to promote and strengthen regional cooperation in Africa.

Source: T. Voeten/ILO)

Regional cooperation has many dividends for the region, fostering investor confidence and encouraging investment in science and technology, and many other opportunities for sustainable development. Environment is a major factor in promoting such cooperation, building upon established frameworks such as MEAs, river basin commissions and transboundary national parks. Conflict and war, however, show the immense cost to both human and natural resources when cooperation breaks down. Many millions of people who should otherwise be contributing to national and regional development are often denied this opportunity through displacement and forced migration. Millions of others die prematurely, having made limited contribution to society and Africa’s development. In such a situation, efforts aimed at attaining the MDG targets are bound to fail.

Conflict has affected some of the poorest countries in the region, and has made them even poorer. This can sometimes result in a vicious cycle – therefore, the need for adequate, sustained, wellcoordinated post-conflict rehabilitation strategies. Essential aspects of this include providing training and supporting demobilization programmes of former combatants, to enable them to achieve a sustainable lifestyle. Access to land and natural resources is an important part of this in Africa, especially in densely populated areas, as is innovative utilization of natural resources including expansion into new regional and global markets.

The NEPAD African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) may provide leaders in Africa with an opportunity to make regional cooperation in environmental management a key component of the criteria for peer assessment. Existing mechanisms for conflict resolution and peace-keeping, such as those of the AU and sub-regional organizations, should be strengthened through consensus building. However, there is a need to avoid competition and duplication between different institutions.

Developed countries, for their part, need to support African efforts by fulfilling financial pledges and privileging humanitarian ideals above geo-strategic interests. Such support would be in the spirit of MDG 8. Aid and trade agreements should take greater account of the actual and potential conflictual aspects of natural resource extraction, processing, and sale. For example, aid packages to countries where natural resource extraction is problematic could be conditional on improved accountability of related financial transactions, and/or effective environmental and social impact assessments.

This will require a shift away from the current security focus (international terrorism) by most major donor agencies. However, external regulation is affected by various technical and political constraints, and hence good domestic governance is a more effective means of limiting the capacities of actors to use natural resources to finance conflict.

In order to prevent conflict, the root causes of conflict should be addressed, and sustainable and equitable development must take place. Such development would go beyond macro-economic expansion, and would be pro-poor in nature, geographically balanced within each particular country, and would involve the enhancement of the skills-base in each country. Equity needs to be a key feature of national and sub-regional economic development. This kind of thinking is reflected in the various founding documents of the AU, SADC, NEPAD and other African institutions. There is a large degree of convergence on issues of security: most see development, freedom and peace-building as essential parts of a multidimensional approach to addressing Africa’s problems. The importance of a comprehensive, structural approach has also been described in the Carnegie Commission’s report on Preventing Deadly Conflict.

Africa’s governments need to remember:

“There can be no peace without equitable development, and there can be no development without sustainable management of the environment in a democratic and peaceful space.”PROFESSOR WANGARI MAATHAI, NOBEL PEACE PRIZE LAUREATE2004 CITED IN LEAN 2005

Further reading

- Abrams, L., 2001. Report of the Workshop on the Establishment of an International Discourse on Development in the Nile Basin: Finding a Platform for Engagement. Gland, 10-12 January.

- African Wildlife Foundation (2003). Africa Launches the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park. African Wildlife Foundation,White River.

- Akindele, F. and Senyane, R. (eds. 2004). The Irony of “White Gold”. Transformation Resource Centre, Morija.

- AMCEN, 1985. Resolution adopted by the conference at its first session. African Ministerial Conference on the Environment. UNEP/AEC 1/2: Proceedings of the First Session of the African Ministerial Conference on the Environment, Cairo, Egypt, 16-18 December.

- Carnegie Commission on Preventing Deadly Conflict, 1997. Preventing Deadly Conflict – Final Report. Carnegie Corporation of New York,New York.

- COMIFAC, 2004. Declaration de Yaoundé, Sommet des Chefs D’etat D’Afrique Centrale Sur la Conservation et al Gestion Durable des Forets Tropicales, 17 Mars 1999,Yaounde, Cameroon. Commission des Forêsts d’Afrique Centrale.

- Conca, K. and Dabelko, G.D., 2002. Problems and Possibilities of Environmental Peacemaking. In Environmental Peacemaking (eds. Conca, K. and Dabelko, G.D.), pp 220-34.Woodrow Wilson Centre Press,Washington, D.C.

- ECA, 2000. Transboundary River/Lake Basin Water Development in Africa: Prospects, Problems, and Achievements. United Nations Economic Commission for Africa,Addis Ababa.

- Ghobarah, H., Huth,P., Russett, B., and King, G., 2001. The Political Economy of Comparative Human Misery and Well-being. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, SanFrancisco, September 2001.

- Ginwala, F., 2003. Textbox 1.1 Rethinking Security: An Imperative for Africa? In Human Security Now (CHS), p 3. Commission on Human Security, New York.

- Government of Uganda, 2002. The Nile Basin Initiative Act. Uganda Gazette, Entebbe.

- Hoover, R., 2001. Pipe Dreams. The World Bank’s Failed Efforts to Restore Lives and Livelihoods of Dam-affected People in Lesotho. International Rivers Network, Berkeley.

- ICGLR, 2003. International Conference on Peace, Security,Democracy and Development in the Great Lakes Region: a Concept Paper. International Conference on the Great Lakes Region.

- Kameri-Mbote, P., 2004. http://www.boell.org/docs/E&S_Publication_Document_FINAL.pdf From Conflict to Cooperation in the Management of Transboundary Waters: The Nile Experience]. In Linking Environment and Security: Conflict Prevention and Peacemaking in East and Horn of Africa (ed. Berthold, M.), pp. 11-24. Heinrich Böll Foundation, Washington, D.C.

- Le Billon, P., 2003. Getting it Done: Instruments of Enforcement. In Natural Resources and Violent Conflict: Options and Actions (eds. Bannon, I. and Collier, P.), pp. 215-86.World Bank,Washington, D.C.

- Marshall, L. 2003. Africa Park Sets Stage for Cross-Border Collaboration. National Geographic News, 5 September.

- Mbeki, T., 1999. Speech at the Launch of the African Renaissance Institute, Pretoria October 11 1999. President of South Africa, Thabo Mbeki. South African Department of Foreign Affairs,Addis Ababa/ Pretoria.

- Michailof, S., Kostner, M., Devictor, X., 2002. Post-Conflict Recovery in Africa: An Agenda for the Africa Region. Africa Region Working Paper Series No. 30.World Bank,Washington, D.C.

- Mohamed-Katerere, J.C., 2001. Review of the Legal and Policy Framework for Transboundary Natural Resource Management in Southern Africa. Paper No 3, IUCN-ROSA Series on Transboundary Natural Resource Management. IUCN – The World Conservation Union, Harare.

- NBI, 2005. NBI-Background. Nile Basin Initiative.

- New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD).

- NHI, IUCN and USAID/RCSA, 2005. Sharing Water: Towards a Transboundary Consensus on the Management of the Okavango River Basin. National Heritage Institute, IUCN – The World Conservation Union and United States Agency for International Development Regional Office for Southern Africa. United States Agency for International Development.

- Nile-COM, 1999. Policy Guidelines for the Nile River Basin Strategic Action Programme. Council of Ministers of Water Affairs of the Nile Basin Countries.

- OSAA, 2005. Human Security in Africa. United Nations Office of the Special Adviser on Africa, New York.

- Norwegian Refugee Council (2004). Internal Displacement: A Global Overview of Trends and Developments in 2003. Global Internally Displaced Persons Project / Norwegian Refugee Council, Geneva.

- OSU, UNEP and FAO, 2002. Atlas of International Freshwater Agreements. Oregon State University, United Nations Environment Programme and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi.

- RBM/WHO, 2003. Malaria in Africa. Roll Back Malaria/World Health Organization.

- Rehn, E. and Johnson Sirleaf, E., 2002. resources/item_detail.php?ProductID=17 Women, War and Peace: The Independent Experts’ Assessment on the Impact of Armed Conflict on Women and Women’s Role in Peace-building. Progress of the World’s Women 2002,Vol. 1. United Nations Fund for Women, New York.

- Russell, D., 1989. Lives of Courage: Women for a New South Africa. Basic Books, New York.

- Southafrica.info, 2004. Africa’s Biggest Water Project. Southafrica.info, 17 March.

- Swatuk, L.A., 2002. Environmental Cooperation for Regional Peace and Security in Southern Africa. In Environmental Peacemaking (eds. Conca, K. and Dabelko, G.D.), pp 120-60.Woodrow Wilson Centre Press, Washington, D.C.

- Turton, A. and Henwood, R. (eds. 2002). Hydropolitics in the Developing World: a Southern African Perspective. African Water Issues Research Unit, Pretoria.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2003. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report. Juta, Cape Town.

- UN, 1998. The Causes of Conflict and the Promotion of Durable Peace and Sustainable Development in Africa. Report of the Secretary General. United Nations, New York.

- UN, 1992. Rio Declaration on Environment and Development. In Report of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3-14 June.A/CONF.151/26 (Vol. I.Annex 1).

- UNEP, 2006. Africa Environment Outlook 2.

- UNHCR, 2004. 2003 Global Refugee Trends. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Geneva.

- World Bank, 2000. Can Africa Claim the 21st Century? The World Bank, Washington, D.C.

|

|

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |