Interlinkages: environment and policy web in Africa

“Environment and development are not separate challenges; they are inexorably linked. Development cannot subsist upon a deteriorating environmental resource base; the environment cannot be protected when growth leaves out of account the costs of environmental destruction.” ~ World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED 1987)

Introduction

Understanding the big picture of the human-environment nexus, with its complex interactions in and across ecosystems as well as in and across human systems, is essential if policy and action responses are to contribute to the goals of sustainable development and improved human well-being. The need to focus on interlinkages and interdependencies in environmental problem solving and in defining opportunities moved to the centre of policy concerns with the 1987 report of the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) (also know as the Brundtland Commission) Our Common Future. The Brundtland report emphasizes that Africa, along with all other regions of the world, does not face separate challenges: “An environmental crisis, a development crisis, an energy crisis. They are all one” (WCED 1987). These links, between challenges in different sectors, are the basis of an interlinkages approach. In making the case for such an approach nearly two decades ago, and long before the term came into vogue, the Brundtland Commission’s visionary and agenda-setting report, identified the relationship between different sectors and the need for planning, decision making and policy frameworks that take account of these links: “These problems cannot be treated separately by fragmented institutions and policies. They are linked in a complex system of cause and effect.” and “Economics and ecology must be completely integrated in decision making and law making processes not just to protect the environment, but also to protect and promote development.” Box 1: Interlinkages defined (Source: Malabed 2001) Environmental problems are never strictly linear, even though some cause-and-effect relationships can be shown, but are a part of a complex web of interactions. This chapter highlights some of the challenges facing Africa which have strong links to the environment. Some of these challenges are analysed sectorally or thematically, but they are all interlinked. Finding opportunities for improved environmental management, as well as for human development, almost always goes beyond any given sector, demanding that new levels of cooperation and collaboration are found in governance, in policy responses, and in environmental management. Deforestation (Interlinkages: environment and policy web in Africa) , for example, is not just about trees but about changing forest landscapes and ecosystems which have implications for biodiversity and water catchment management. Deforestation may increase run-off, thus accelerating soil erosion and siltation of rivers and lakes; it may also affect soil fertility. In addition to these biophysical interactions, there are also links between forest changes and human society. Deforestation may be the product of multiple and interlinked changes in human society, including the lack of livelihood options, new pressures brought about by demographic changes, an economic environment that does not support value-adding activities and thus results in ever higher levels of harvesting, and so on. It may also affect human wellbeing by closing some opportunities, threatening cultures and knowledge systems closely related to forest resources, undercutting agricultural and livestock productivity, and increasing poor health as access to medicinal plants, wild meat and wild fruits that supplement local diets are lost.

By adopting an interlinkages approach to the challenges facing Africa, policy may maximize the opportunities across a number of domains.

Building interlinkages

An interlinkages approach recognizes the complexities inherent in ecosystem dynamics and their interface with the equally complex social, economic and political dynamics inherent in human development and governance, particularly policies, laws and institutions. Its value lies in the dynamic understanding and problem solving opportunities it brings to addressing complex cross-sectoral issues. The interlinkages concept stresses the importance of coordination of action across the relevant dimensions of sustainable development including environmental, social and economic issues. Developing an interlinkages approach requires addressing the complexity of environmental challenges. Box 1 defines interlinkages.

In each situation, policymakers and resource managers will need to determine the appropriate level of interlinkages to address any particular problem. This will need to take into account the multiple scales of interaction, the high incidence of non-linear trajectories, uncertainty, time lags, and the common and conflicting interests of multiple stakeholders. Successful approaches involve considering, among other things, that:

- Trade and investment, research and development, science and technology, and health and poverty are all important interlinked drivers of environmental change with both positive and negative impacts.

- Green environmental issues are linked to brown environmental issues, such as pollution and solid wastes, both impacting on the environment and on development opportunities.

- Processes which improve cooperation between science, policy making, practice and management can create robust and dynamic response systems that provide for better understanding of the issues and more effective responses.

- In any given situation, there may be multiple knowledge systems related to environmental management; different stakeholders may have different interests and values, indicating a need for processes that not only recognize, but also mediate and make trade-offs between these interests.

- An added challenge is that institutions – laws and policies – operate at multiple scales. The reach and jurisdiction of organizations also vary considerably and thus interlinkages in governance are important.

- Opportunities for improved participation and the recognition of public values, concerns and priorities in shaping policies are necessary to create linkages between these diverse levels, and to build collaborative and sustainable governance and management systems. These responses should include creating opportunities for participation in regional and sub-regional processes as well as creating more effective decentralization and devolution policies at the national level.

- The complexity of environmental problems – and thus the identification of opportunities – needs to be addressed through, among other things, analysing the interlinkages between and among the biophysical aspects of the environment and existing policy responses, including sub-regional, regional and international multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs), and institutions in the different sectors and at different levels, and how these affect the sustainability of the environment-human complex.

- Variations in temporal and spatial scales between different changes within the environment-human complex will need to be identified. Focusing on a single scale may obscure processes that only become obvious at finer or broader scales. Changes within natural systems and human systems occur at different temporal and spatial scales; for example, environmental shocks are episodic, rainy seasons are cyclic and droughts are stochastic. Stochastic events are those having a random probability distribution or pattern that can be analysed statistically but not predicted precisely. The spatial range of impact of these phenomena may vary. The multiple links between local livelihood sustainability and global climate change indicate the complex and multilevel interactions and interlinkages between human and environmental systems.

The interlinkages concept promotes building cooperation across institutional boundaries and between different interests at and across multiple scales. It can, for example, be used to establish links and build synergies between departments of meteorology, water (Water resources) and agriculture in addressing issues related to water availability, distribution, allocation and use. In some circumstances, institutional links between institutions and organizations operating at different spatial scales will be required. Water basins, for example, cut across national boundaries and there are multiple users and stakeholders. The progress made in eradicating Dracunculus medinensis, Guinea worm, lies in the strong interlinkages approach taken between different sectors, such as health, education and water management, and across countries, as shown in Box 2.

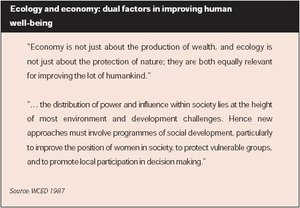

A key objective of the interlinkages approach is to demonstrate the importance of the environment and its sound management to other sectors, and thus to ensure that holistic approaches are taken to problem solving so that advancements can be made in human well-being, human vulnerability to environmental change can be minimized, and the environmental base can be sustained. Box 3 emphasizes the environment-economy-human well-being interlinkage identified by the Brundtland Commission, which has since gained wide recognition in many global, regional and national policies and strategies.

Various global and regional policy responses, such as the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) framework, the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), and the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) Johannesburg Plan of Implementation, individually and collectively, provide opportunities for enhancing synergies, promoting interlinkages among the environmental challenges, and mainstreaming the environment within and across institutional, temporal and spatial boundaries. Box 4 highlights some of the interlinkages related to the implementation of activities, at a national level, to address the MDGs and demonstrates that the appropriateness of such an approach will vary from country to country.

Adopting an interlinkages approach in the formulation of policy and the development of programmes can help to ensure that interventions are more relevant, robust and effective, and that these policies are based on principles that are cross-sectoral and interdisciplinary. This approach can also help to sharpen the focus of policy and action, while at the same time ensuring that spatial and temporal factors across multiple sectors and ecosystems are also fully considered. Interlinkages may help bring into focus certain issues, such as gender, that are often neglected. When effective institutional systems are developed to implement an interlinkages approach, it can give policymakers the advantage of having a better grasp of the range of options available, the costs and benefits of their decisions, and how to determine the interdepartmental links that are necessary to promote “joined-up policies.”

Further reading

- Keeley, J. and Scoones, I., 2003. Understanding Environmental Policy Processes: Cases from Africa. Earthscan, London.

- Lovell, C., Mandondo, A. and Moriarty, P., 2003. The question of scale in Integrated Natural Resource Management. In Integrated Natural Resources Management: Linking Productivity, the Environment and Development (eds. Campbell, B.M. and Sayer, J.A.), pp 109-38. CABI Publishing, Oxford.

- Malabed, R. N., 2001. Ecosystem Approach and Interlinkages: A Socio-Ecological Approach to Natural and Human Ecosystems. Discussion Paper Series 2001-005. United Nations University, Tokyo.

- Roberts, J. L., 2004. Case Study 12: Malaria Control in Mauritius. In AEO Case Studies: Human Vulnerability to Environmental Change. (UNEP), pp 161-8. Earthprint, London.

- Sayer, J. and Campbell, B., 2004. The Science of Sustainable Development: Local Livelihoods and the Global Environment. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

- UNEP, 2006. Africa Environment Outlook 2.

- WCED, 1987. Our Common Future.World Commission on Environment and Development. Oxford University Press, Oxford

- WHO, 2006a. Dracunculiasis (Guinea-Worm). World Health Organization, Geneva.

- WHO, 2006b. Water Related Diseases. Guinea-Worm Disease (Dracunculiasis). World Health Organization, Geneva.

|

|

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |