Regulation of toxic chemicals

Contents

Introduction

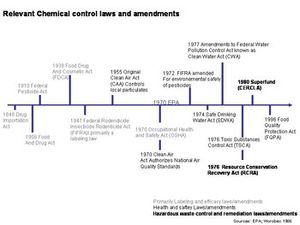

The need for government attention to and regulation of chemicals increased as the chemical and Industrial Revolution (Regulation of toxic chemicals) progressed, and as the human-chemical relationship intensified. As will become clear in this article, the great majority of chemical control laws, from limits on pesticide residues (up until very recently) to ‘allowable’ concentrations of chemicals in surface or drinking waters, have focused on control of individual chemicals. Several of the chemical control laws are reviewed below (Figure 1).

Federal Food Drug and Cosmetic Act

Prior to the late 19th-early 20th centuries in the United States, there were virtually no controls on food additives, drug efficacy, or the safety of either. One of the earliest laws concerning chemical or drug use and development was the Drug Importation Act of 1848. Apparently short-lived, this early law was enacted to protect the public from impure, degraded, or ineffective drugs that were produced elsewhere in the world and exported to the U.S. (Figure 1). With the development and sale of unregulated ‘remedies’ and all sorts of food preservation schemes (refrigerators as we know them were not developed until the last quarter of the 19th century), it soon became clear that some kind of regulation was necessary for consistent consumer protection. Concerns about adulteration, including use of preservatives in foods, spurred some of the early human studies on the health effects of adulterants. Under the direction of Dr. Harvey Wiley, the second chief chemist of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Division of Chemistry, preservatives were tested by his now infamous “poison squad,” a group of USDA employees who apparently volunteered to ingest to test the toxicity of several commonly used food preservatives of the day (formaldehyde and sulphites, for example, were amongst the first to be explored). These studies resulted in the creation of such early food and drug control laws as the Food and Drug Act of 1906. Our current Federal Food Drug and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA) authorizes assessments of the safety of new drugs, food additives, and colors; and it specifies tolerance levels for pesticides and other chemicals that may occur in foods.

Not surprisingly, from the earliest tests conducted by Wiley to many current toxicity tests required of new food additives, chemicals are tested and regulated on a single-chemical basis. Pesticide tolerances for a particular fruit or vegetable, for example, include consideration of the reference dose (RfD) for the pesticide (as an individual chemical), and consumption rates, maximum pesticide residues found during experimental exposures, and other uses and residue levels on other crops. Concern for multiple or mixed, pesticide residues in foods, however, has prompted the FFDCA recently to act in concert with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to address the issue of chemical mixture exposure in foods.

Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act

Prior to the 1970’s the early Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) under the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) was geared essentially towards protecting consumers from ineffective products. It really was not until amendments to the law in the 1970s that FIFRA was re-directed to consider the environmental fate and toxic effects of these chemicals and to protecting consumers and the environment from these products. The changes in FIFRA gave a boost to the newly emerging field of environmental toxicology. Nonetheless, fulfilling the regulatory requirements to evaluate adverse environmental effects of individual pesticides, and building upon the existing body of toxicology, environmental toxicologists focused, once again, on the evaluation of single chemicals.

Recent amendments made to both FIFRA and the FFDCA by the way of the Food Quality Protection Act (FQPA), have been hailed as groundbreaking approaches to pesticide regulation, for their departure from regulation based upon single chemicals. The FQPA is changing the way pesticide residues are regulated by setting ‘health-based’ standards for ALL pesticides in foods. ‘All’ in this case means combined residues from several different pesticides, or, chemical mixtures. The importance of this amendment, with respect to chemical mixtures should not be underestimated. This is one of the first attempts to regulate the permitting of individual chemicals based on their potential for combined toxicity. It will require development of innovative and reliable techniques to address combined toxicity. Although we will discuss the methodology used to determine new pesticide limits later, we should point out that this combined approach for now is limited to similarly acting pesticides. Currently, the FQPA does not address pesticide mixtures that act through different mechanisms. For example, several different organophosphate pesticides may occur in combination along with arsenic. The mixtures assessment will consider the combination of organophosphates, but nonetheless will assess arsenic separately. The rational for only extending combined toxicity to similarly acting pesticides should become clear as we discuss the toxicological tools available for such work.

Together, the FFDCA and FIFRA regulate a large share of chemicals to which humans are likely to be exposed, by setting tolerances and allowable concentrations for chemicals, one chemical at a time, up until 1997. This is almost a one hundred year history of single chemical regulation. Not only does toxicology and regulatory policy have a long history based upon the single-chemical approach, but they must now address the reality of chemical mixtures. Although clearly the single-chemical approach has provided a strong foundation for chemical control, the utility or relevance of these techniques for addressing multiple chemical exposures is currently unclear.

Occupational Health and Safety Act

The Occupational Health and Safety Act (OSHA), enacted in 1970, is relevant to our discussion because it set forth some of the first risk assessment techniques for dealing with chemical mixtures. It is interesting to note that occupational toxicology, one of the earliest branches of toxicology, was one of last to regulate the use of and exposure to chemicals. OSHA was designed, in part, to protect workers from exposure to harmful chemicals through establishment of standards and guidelines combined with monitoring of exposure levels in the workplace. This is not to say that industrial guidelines for exposure did not exist prior to OSHA. Industry, industrial hygienists (or occupational toxicologists), and workers alike recognized the need for worker protection from chemicals and other hazards, although depending on whose history you read, the degree and desire for protection varies widely. Without going into the details, in the early 1940s, prior to any federal regulation, the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH), began developing what eventually became known as Threshold Limit Values (TLV) for exposure to industrial chemicals. As these were set prior to the founding of OSHA, there has been some controversy over the degree of industrial influence in the setting of TLVs.

Since industrial workers were seldom exposed to one chemical at a time, the ACGIH established a forward-looking methodology to address exposure to chemical mixtures in 1963. The method was fairly simple: unless there was evidence to the contrary, mixtures of chemicals that act on the same organ were to be treated in an additive manner using what they called “dose addition”. It is this methodology, along with the TLVs, that was adopted by OSHA when it was enacted in 1970, and which has been modified for use today by such agencies as the EPA. It is important to note this early consideration of mixtures, at least for the relatively high levels of exposure experienced in occupational settings, even though 40 years later we are still grappling with how to advance beyond the simple concept of additivity.

Toxic Substances Control Act

The Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), passed in 1976. TSCA was developed to fill in the gaps of previously existing laws, all of which were designed to protect human health and the environment from chemicals released by industry and by all of us each day (such as through driving, flushing the toilet, and even taking pharmaceuticals). Under TSCA, the EPA can evaluate the toxic effects of new and existing chemicals on both humans and on the environment. Also, it mandates the tracking of the thousands of chemicals that are produced or imported into the country. Although TSCA mentions testing and assessment of individual chemicals and mixtures, there are no apparent guidelines for assessment of mixtures. Additionally, when referring to mixtures, the language of TSCA seems to refer to commercial or industrial mixtures (an intentionally prepared, and likely well defined mixture).

In 2006 the European Union (EU) enacted REACH, (Registration, Evaluation and Authorization of Chemicals)a new approach to chemical regulation, that became effective in 2007. REACH isessentially a mirror image of TSCA. While TSCA requires the EPA to demonstrate that a chemical is a risk to human or environmental health, REACH requires that the manufacturers test and ensure that chemicals do not pose such risks. Additionally, under REACH many old or existing chemicals will also require testing, unlike TSCA. Since chemicals imported into the EU also fall under REACH, the legislation may impact some chemicals produced in the U.S. as well.

A recent and evolving challenge for EPA is the regulation of nanoscale materials. A nanomaterial is defined as having at least one dimension that is 100 nanometers or smaller (though this definition is evolving as researchers and regulators become more familiar with the universe of nanomaterials currently under development). According to the Project on Emerging Nanotechnology, there are over 1000 nanotechnology-based consumer products in use, as identified by manufacturers. Some of these nanomaterials are versions of larger bulk material regulated already under TSCA—for example, nano-size titanium dioxide used in sunscreens—while others (for example, quantum dots containing mixtures of metals, polymers and other organic materials) represent new combinations. Although new chemical substances are subject to review and reporting under TSCA—existing substances even if manufactured as nanomaterials are not. Some scientists are concerned that nanosized particles may behave differently than their larger "bulk" counterparts (this difference in behavior is, in part, why some chemicals are useful as nanomaterials) and as such should be reviewed as new materials. This is an area of active research for toxicologists and regulators alike.

Together, these chemical control laws—FFDCA, FIFRA, OSHA and TSCA—make up the bulk of laws that govern the production, use, and disposal of chemicals found in drugs, food, consumer products, and the workplace. It makes some sense that these laws, enacted for the most part in the early-mid 20th century, focused on individual chemicals. A great deal of energy and funding was channeled towards the further use and development of single-chemical testing and the rapid growth of the field of toxicology as a result of these laws. Further, other than OSHA, regulation of chemicals based on consideration of combined effects is a very recent development.

Environmental toxicology: a regulatory beginning?

With the establishment of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1970, several other laws and regulations were enacted or strengthened. The intention of these laws was to control the release of chemicals in the air, water and terrestrial environments, and direct remediation or cleaning up of those chemicals already released. While still regulating release or cleanup on an individual chemical basis, these laws are also designed to evaluate the impact of all toxic chemicals released on health and environment.

Clean Air Act

The oldest of these laws is the Clean Air Act (CAA), enacted in 1955. The CAA was created to ameliorate increasing smog problems across the country, most unfortunately exemplified in the Donora Smog of 1948. The Donora incident occurred in a small steel mill town, and it sickened and killed many of the town’s residents (this story was recently recounted by Devra Davis in "When Smoke Ran Like Water". Early regulations sought to control particulate matter released from factory smokestacks. Subsequent amendments, however, provided the newly formed EPA a chance to develop criteria and set standards that would be protective of the public. Interestingly, these later additions to the CAA allowed for:

- the cumulative impact of specific chemicals from multiple sources;

- consideration of particularly vulnerable or susceptible populations; and

- consideration of other pollutants that may interact with the pollutant under consideration.

Clean Water Act

Once again it was not until unavoidably blatant examples of environmental degradation—this time of the nation’s surface water—that the legislative branch initiated the process of tightening up laws to protect and remediate our waters. This included the now infamous Cuyahoga River fire, and the James River Kepone incidents—the latter resulting in the closing of the river to all fishing following large releases of the insecticide Kepone into water discharges and soil by a local manufacturer. The Clean Water Act (CWA) is the result of years of revision and amendments to earlier acts that were clearly ineffective towards protection of surface waters. Amendments in 1972 and later in 1977 resulted in an Act regulating release of chemicals into the nation’s waterways, and required EPA to develop criteria on a chemical-by-chemical basis, to be used by individual states in setting water quality standards.

The Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) approach is also a requirement under the CWA. It requires regulators to take into account water quality, water chemistry, and the cumulative impacts of individual chemicals, providing a more holistic means of evaluating water quality than simply regulating individual chemicals. Apparently, the application of TMDLs required legal action by citizens’ organizations against the EPA. The TMDL concept is one of the few acts acknowledging the presence of chemical mixtures, multiple impacts, and the potential for interaction amongst chemical contaminants.

It is currently unclear how often the impacts of multiple chemicals are actually addressed by the EPA. The CWA does however have one tool in its arsenal that does directly address chemical mixtures at least as complex mixtures, the Whole Effluent Toxicity (WET) test. Here, point source or “end of pipe” discharges are tested as a whole using various aquatic organisms, rather than relying solely upon water quality criteria developed for individual chemicals within the effluent (although EPA recommends using the two together for water quality protection). The WET test could be categorized as a test of complex mixtures (many uncharacterized chemicals), since it is not necessary that individual components of the mixture be identified.

To date, the majority of chemical control laws for our nation’s waters remains on an individual chemical basis, even though, as recent surveys clearly indicate, many watersheds or surface water systems are contaminated with mind-boggling combinations of both regulated (those chemicals with EPA-established criteria and state standards) and unregulated chemicals (those that no one ever expected to turn up in measurable quantities in our water systems).

Safe Drinking Water Act

The other portion of our water supply is drinking water. The Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA), enacted in 1974 and subsequently amended in 1986 and 1996, was intended to protect drinking water and fill gaps left by the “surface water”-focused Clean Water Act (CWA) (i.e., to protect groundwater resources in addition to any surface waters that serve as drinking water resources). As with the other regulatory acts, the SDWA regulates on an individual chemical basis, with no consideration for combined effects of chemical mixtures that may occur in drinking water.

These chemical release laws, much like many of the chemical control laws, regulate on a single chemical basis. Much of the underlying toxicology and testing that support these laws is very similar to the methodology used to develop the earlier chemical control laws. While it is easy, in hindsight, to criticize the creators of this approach, it really is merely the outgrowth of decades of single-chemical study designed to regulate one chemical at a time from industrial or municipal dischargers—whether or not they are commonly released alongside many other chemicals. The single-chemical approach seemed to be based on a common assumption for many toxicologists and regulators: that for chemicals below levels known to cause effects (e.g., the No Observed Adverse Effect Level[NOAELs]), interactions would either not occur or not be important. There was no need, therefore, to be concerned with interactions if chemicals regulations and criteria were based upon the NOAELs. There is, however, growing concern among toxicologists and regulators that regulating chemicals one chemical at a time is not adequately protective of humans and the environment.

The RCRA and The CERCLA

The laws previously discussed deal with “allowable” releases into our air or water. The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) of 1976 and the Comprehensive Environmental Response Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA), or “Superfund,” of 1980, were enacted to reduce the potential for industrial chemicals to get to the point of release, and to cleanup currently existing contamination. Within these laws, the potential health impacts associated with combined chemical exposure is addressed through EPA’s Supplementary Guidance for Conducting Health Risk Assessment of Chemical Mixtures.

Resource Conservation and Recovery Act

The primary goal of RCRA is to protect humans and the environment from contaminants by providing the EPA with the ability to control chemicals from their production to their disposal (or reuse). RCRA applies to both active and future facilities (including many federal facility or military sites). Authority for ‘corrective action for hazardous releases’ (or remediation) under RCRA came in 1984 with the Hazardous and Solid Waste Amendments (HSWA). This allowed for remediation of facilities seeking RCRA permits and “compels corrective action for releases that have migrated beyond the facility property boundary.” Additionally, the guidance document for RCRA facility investigation acknowledges that in many situations it is appropriate to consider impacts of combined chemical exposures, even if concentrations of individual chemicals do not exceed action levels.

Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act

CERCLA, or Superfund, enacted in 1980, was designed to deal with hazardous waste that was for the most part not regulate under RCRA or any other environmental law—those chemicals released into the environment by closed and abandoned hazardous waste sites. Under CERCLA, hazardous waste sites are ranked according to cleanup priority (based on the degree of hazard they present); those deemed most hazardous are placed on the National Priorities List or NPL.

Further Reading

- Breysse, P. 1991. ACGIS TLVs: A Critical Analysis of the Documentation. Am J. Ind. Med. 20:423-427.

- Castleman, B., Ziem, G. 1988. Corporate Influence on Threshold Limit Values. American J. Indust. Med. 13:531-559.

- CERCLA overview, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

- Clean Water Act Information, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

- Davis, D. 2002. When Smoke Ran Like Water. Basic Books, NY, NY.

- Federal Food Drug and Cosmetic Act, U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- Food Drug and Cosmetic Law Journal 39: 2-73.

- Food Quality Protection Act, Highlights, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

- History of the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH), ACGIH

- Hutt, P., Hutt, P. 1984. A History of Government Regulation of Adulteration and Misbranding of Food.

- Markowitz, G., Rosner, D. 2002. Deceit and Denial. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA.

- National Acadamy of Science publication, Contaminated Sediments: Assessment and Remediation, about the James River Kepone Incident by Robert Huggett, Excerpt

- National Acadamy of Science publication, Contaminated Sediments: Assessment and Remediation, about the James River Kepone Incident by Robert Huggett, Full Report

- Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies

- RCRA, basic description, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

- Roach, S., Rappaport, S. 1990. But They are not Thresholds: A Critical Analysis of the Documentation of Threshold Limit Values. Am. J. Indust. Med. 17:727-753.

- Safe Drinking Water Act Description, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

- TMDL process, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

- TMDL program overview and the need for citizen action in order to prompt development of TMDLs, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

- TSCA, full text; provides language on types of mixtures within TSCA, U.S. Code Collection, Cornell Law School

- TSCA, General Information, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

- Nanomaterials, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

- Whole Effluent Toxicity Test, and its use in combination with single water quality criteria, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

- Wiley, H. 1907. Influence of Food Preservatives and Artificial Colors on Digestion and Health. USDA Bureau of Chemistry Bull. 84 (3).

- Worobec, M., 1984. Toxic Substances Primer. The Bureau of National Affairs, Inc. Washington, D.C.

1 Comment

Natalie Haddon wrote: 05-03-2011 11:27:06

Very helpful and a great resource!