Harp seal

The Harp seal (scientific name:Pagophilus groenlandicus) is one of 19 species of marine mammals in the family of True seals. Together with the families of Eared seals and Walruses, True seals form the group of marine mammals known as pinnipeds.

| Conservation Status |

|

Scientific Classification Kingdom: Animalia (Animals) |

| Common Names: Beater Bedlamer Greenland Seal Jumping Seal Saddle-backed Seal Harp seal |

The Harp seal derives its common name from the dark harp shaped mark on its back.

Contents

Physical Description

Harp seals can grow up to two metres (m) in length and 160 kilograms (kg) in body mass, with females being slightly smaller in size than males. Males are silver gray with black heads and black "horseshoe" or "harp-shaped" markings on their backs. Females are paler in colour and have markings that are less distinct. Often the colour of females is broken up into spots. Usually, the colouration of the seals changes with age. In April and May, harp seals shed their coats and grow new ones.

Distinguishing characteristics: adult is white with dark "harp" on back, dark face. The pup is white (and is termed a whitecoat), moults to grey coat with dark spots (then termed beater) within three weeks. Immatures (individuals 14 months and older) are called bedlamers.

Reproduction

Males fight for access to females by using their teeth and flippers. Mating occurs on the ice and the seals are monogamous for the season. Sexual maturity is reached in males at six years and in females at five years. The reproductive season for harp seals is from the end of February to the end of March.

The seals migrate south to breed and molt. Gestation lasts 11.5 months, with 4.5 months dormancy of the fertilized ovum (delayed implantation). Females give birth to one pup, occasionally to twins.

The pups weigh about 10 kg and are suckled for about 12 days. The milk is rich in fat and mostly becomes blubber. Pups can gain up to two kg a day. During lactation, the mother feeds on little if anything at all. After weaning, the young spend up to 10 days alone until their embryonic hair is replaced by proper fur.

Behaviour

Harp seals are solitary animals except during breeding season, when tens of thousands of individuals congregate. There is no social organization in these aggregations. The seals seem to be seasonally monogamous. They migrate south in autumn and retreat north in summer with the receding ice pack. The migration can total 6000 to 8000 kilometres. Harp seals are powerful high-speed swimmers capable of moving quickly on the ice and diving to depths of over 270 m.

Their senses of vision and hearing are very acute, especially under water, while their sense of smell is not as sensitive.

Distribution

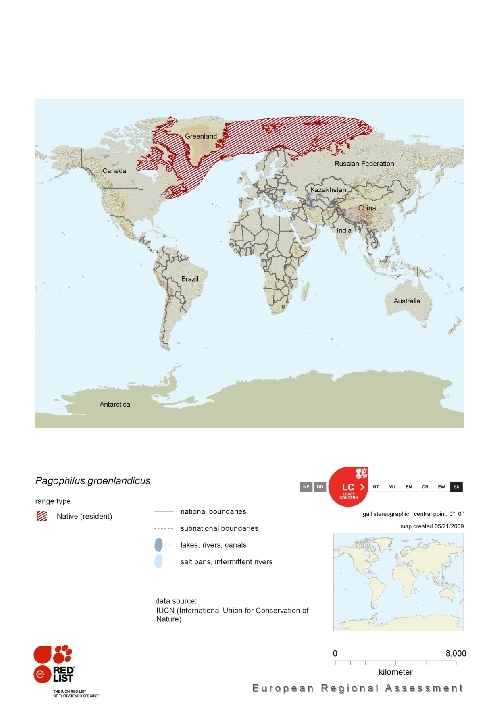

Harp seals are found in the Arctic and North Atlantic ranging from the Kara and Berents Seas to the waters surrounding Greenland and Newfoundland. There are three populations of harp seals: one that breeds in the Gulf of St. Lawrence off the coast of Newfoundland, another that breeds north of Jan Mayen island in the Greenland Sea, and a third that breeds in the White Sea.

Habitat

Harp Seal. Sketch by Henry W. Elliott.

Harp Seal. Sketch by Henry W. Elliott.

Harp seals live in the open sea on the edge of the pack ice. They are dependent on the ice for breeding and molting. They prefer rough, hummocky ice at least 25 centimetres (cm) thick, and they maintain natural holes ranging from 60 to 90 cm in diameter for purposes of access to water and breathing. During the breeding season, up to 40 seals may share a breathing hole.

Predators

Harp seals are preyed upon by sharks and killer whales.

Food Habits

Harp seals are carnivorous, feeding on fish, and crabs and other invertebrates. The fish taken include capelin, arctic cod, cod, herring, and halibut. Small crabs are the primary source of food after weaning.

Conservation Status

Although there are large number of these seals, many are killed by hunters each year, since the fur has commercial value. The clubbing of large numbers of Harp seals within Canada has received international attention, and the very large number of takings has been reduced somewhat over the last two decades. Currently, the population is estimated to be over eight million.

Economic Importance for Humans

Harp seals are second only to fur seals in commercial value. Hunters kill them for fur, oil, and leather. Native peoples of the north kill 10,000 seals a year for food and fiber, and the commercial take is much higher yet.

Harp seals have been long hunted by native peoples of the Arctic, including the northern extremes of Europe. Modern hunting began with Basque whalers sixteenth century. French, and later British, hunters in Canada began taking seals in the following century. In the nineteenth century, ship-based hunting began and the take rose rapidly, before harvesting lead to reduced hunting success in the late 1850s. At this time Norwegians also became very active in seal hunting. During this period the primarly motivation for Harp seals was their oil. However, in the twentieth century seal fur began to be the desired product.

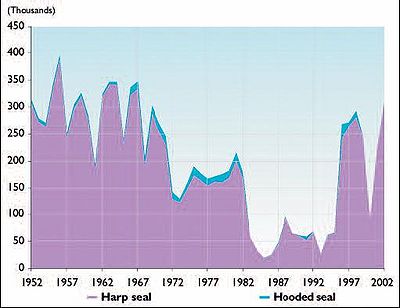

Following a rise in the numbers of seals hunted in the 1950s, the Canadian governmnet began putting limits on the duration of the hunting season which resulting in a modest decline in the take. Canada then took additional steps by protecting adult female seals on thier breeding grounds, closing limiting outside hunting in Canadian waters, and establishing, in 1971, limits on the number of seals that could be taken. In 1983,in response to public opposition to seal hunting, the European Community banned the importation of whitecoat Harp seal skins. In 1987 Canada banned the killing of whitecoats and two years later Norway followed suit.

The total population increased from less than two million in the early 1970's to more than five million in the mid-1990's. The increase was largely due to a reduction in the hunt after 1982. The population stabilized when the hunt was increased in the mid-1990's. Reported Canadian catches of harp seals include harvests off the coast of Newfoundland/Labrador (the Front) and in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Seals caught in both areas belong to the same population: the Northwest Atlantic Harp Seals. The proportion of the population that occurs in the two areas varies among years, as does the relative number of seals caught in each area. Catches from both areas are combined in official statistics and so those presented here are combined “Front” and Gulf of St. Lawrence catches.

On occassion large numbers of seals have moved into regions where they were not present in significant numbers before resulting in significant deaths as bycatch in fisheries. An occurance in 1987 was estimated to have results in 100,000 harp seals killed in 1987.

Further Reading

- Pagophilus groenlandicus (Erxleben, 1777) Encyclopedia of Life (accessed July 19, 2010)

- Pagophilus groenlandicus, Stiles, S., 2001, Animal Diversity Web (accessed July 19, 2010)

- Harp Seal, Seal Conservation Society (accessed July 19, 2010)

- Pagophilus groenlandicus, IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (accessed July 19, 2010)

- The Pinnipeds: Seals, Sea Lions, and Walruses, Marianne Riedman, University of California Press, 1991 ISBN: 0520064984

- Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, Bernd Wursig, Academic Press, 2002 ISBN: 0125513402

- Marine Mammal Research: Conservation beyond Crisis, edited by John E. Reynolds III, William F. Perrin, Randall R. Reeves, Suzanne Montgomery and Timothy J. Ragen, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005 ISBN: 0801882559

- Walker's Mammals of the World, Ronald M. Nowak, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999 ISBN: 0801857899

- Harp Seal, MarineBio.org (accessed July 19, 2010)