Eastern Africa and coastal and marine environments

Contents

- 1 Introduction Figure 1. Coral reefs occur extensively along Africa's east coast. In southern Somalia coral reefs form a barrier along the coast. (Source: NASA (Eastern Africa and coastal and marine environments) 2001)

- 2 Overview of resources The sub-region’s long coastline stretches from the Red Sea, which flanks Eritrea, through the Gulf of Aden, off Djibouti, to the Indian Ocean, off Somalia and Kenya. Most of the coastal zone (Eastern Africa and coastal and marine environments) is arid and, outside the few coastal cities, sparsely populated, except in Kenya where the coast has a monsoonal climate and supports a large and growing population. Figure 2. Lamu-a UNESCO World Heritage site on the Kenyan coast, is a highly acclaimed tourist destination. (Source: S. Koppel)

- 3 Endowments and opportunities

- 4 Challenges faced in realizing development opportunities

- 5 Further reading

Introduction Figure 1. Coral reefs occur extensively along Africa's east coast. In southern Somalia coral reefs form a barrier along the coast. (Source: NASA (Eastern Africa and coastal and marine environments) 2001)

The main concerns are the loss of biodiversity, habitat degradation and the modification of mangrove and coral reef ecosystems. Human-related pressures come from overfishing and fishing-related damage, from urbanization and tourism development, from agriculture and industry, and from damming for hydropower. Other important concerns are the reported dumping of hazardous wastes on Somalia’s shores and coastal waters and climate change (Climate change and development challenges in Africa), contributing to coral bleaching and sea-level rise, which in turn leads to coastal erosion and inundation of coastal lowlands. Another issue is the sporadic infestation of coral reefs by the invasive crown-of-thorns starfish (COTS). The shores facing the Indian Ocean were impacted by the catastrophic tsunami of 26 December 2004, and in Somalia, some 300 people are reported to have died.

Overview of resources The sub-region’s long coastline stretches from the Red Sea, which flanks Eritrea, through the Gulf of Aden, off Djibouti, to the Indian Ocean, off Somalia and Kenya. Most of the coastal zone (Eastern Africa and coastal and marine environments) is arid and, outside the few coastal cities, sparsely populated, except in Kenya where the coast has a monsoonal climate and supports a large and growing population.

Most countries have important marine fisheries resources, as well as the inshore and reef fisheries which are traditionally exploited by artisanal fishers. There are prolific fisheries associated with the upwelling of the Somali Current off the north-eastern coast of Somalia, and seasonally-rich resources off Djibouti and Eritrea. Coral reefs occur extensively, except where there is upwelling or sediment is discharged. Surveys of reefs in the late 1990s, here, and on the shores of the Gulf of Aden, reported reef health to be generally good, and the diversity of coral and reef-associated fauna to be globally significant, with a high level of endemism and species diversity. Reefs occur as an interrupted barrier on Somalia’s southern coast, and in Kenya they fringe a cliff-bounded, intertidal platform extending over some 150 kilometers (km) of the Mombasa shore. Kenya’s coral reefs suffered severe mortality in the 1998 bleaching event, but recovery of coral cover is now at 50-100 percent levels.

Mangroves colonize some sheltered inlets on the Red Sea and in southern Somalia, and in Kenya exist as extensive, lush forests, in the Lamu district, and as linings to tidal creeks, further south; they have a total estimated area of 610 km2. The coral reefs, seagrass beds and mangroves of the Somali Current Large Marine Ecosystem (LME) form a productive and diverse ecosystem of great ecological and socioeconomic importance; the mangroves also providing sanctuary to a wide variety of terrestrial fauna. For the Red Sea, several Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) have been declared or proposed – notably the Dahlak Archipelago marine park (2,000 km2) in Eritrea – but these are mostly lacking effective management plans and enforcement. In Kenya, MPAs, such as the Watamu and Kisite marine national parks, are well established and generally well managed. No effective protection exists on the Somali coast.

Oil and gas exploration is continuing along the Eritrean and Kenyan coasts. The Pleistocene reef limestones provide raw materials for an established cement industry near Mombasa, and in Somalia similar limestones are quarried for aggregate and building stone. In a new coastal development venture in Kenya, mineral sands have been identified as a source of titanium ore.

The [[coastal] zone] has a rich archaeological and cultural heritage which includes the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Site of Lamu Old Town in Kenya, the oldest and best-preserved Swahili settlement in East Africa. Other significant heritage sites in Kenya include Mombasa’s Old Town and Fort Jesus. The Gedi ruins near Malindi, gazetted as a monument in 1927 and now a National Museum, mark an Islamic civilization city.

Endowments and opportunities

Inshore and reef-related fisheries have been a mainstay of the coastal populations and continue to be an essential resource for their livelihoods. The Red Sea coasts of Eritrea and Djibouti support extensive reef-based artisanal fisheries; there are also productive offshore fisheries due to the seasonal upwelling in the Gulf of Aden.

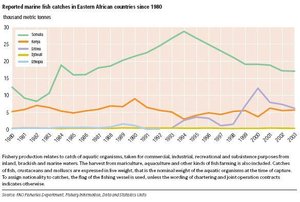

Figure 3. Reported marine fish catches in Eastern Africa countries since 1980. (Source: FAO Fisheries Department)

Figure 3. Reported marine fish catches in Eastern Africa countries since 1980. (Source: FAO Fisheries Department) Fisheries are dominated by foreign fleets, with production far outstripping that of artisanal fishers. Most commercial operations in the prolific fisheries of the Somali Current upwelling are carried out by foreign vessels, many of them illegally. In Kenya, most fishing activity takes place along the reef, with mainly reef- and seagrass-associated fish species being exploited; a few freezer trawlers fish for shrimp in the shallow waters of Ungwana Bay. Little is known of the potential of the offshore fisheries resource in southern Somali and Kenyan waters.

While artisanal and inshore fisheries are generally overharvested, some countries have not yet developed the capacity to fully exploit, or enforce regulation of, their offshore fisheries. But this is changing. Eritrea now places a high priority on the development of commercial fisheries, aiming to increase production three- to fourfold, up to between 50,000 and 60,000 tonnes (t) per year. Some 80 to 85 percent of this production is expected to be generated by the foreign industrial fleet, especially trawlers, but the contribution from artisanal fisheries may also be increased. In Djibouti, pelagic and small tuna species are considered to be significantly underexploited. Djibouti is aiming for an annual maximum sustainable yield (MSY) of 5,000 t, compared with a 2001 level of 350 t.

In Kenya, coastal tourism is a major foreign exchange earner, with its beach and coral reef resources, coastal heritage sites and forest reserves being major assets. Coastal tourism is starting to develop in Djibouti and has shown a moderate growth in Eritrea. In Somalia, ecotourism offers promise, but promise that cannot be realized until stability and effective governance is re-established.

Challenges faced in realizing development opportunities

Adopting transboundary approaches to manage marine and coastal resources is essential if their sustainability is to be ensured. The main transboundary cooperation is within the framework of the Nairobi (involving Kenya and Somalia) and Jeddah (involving Djibouti and Somalia) conventions. For the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden, PERSGA (he Regional Organization for the Conservation of the Environment of the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden) implements the Jeddah Convention. Priority actions have been identified in the Regional Action Plan coordinated by PERSGA in 2003. The Nairobi Convention is administered by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Land-based activities impacting the coastal and marine resources in Kenya are addressed through UNEP as part of the Global Environment Facility (GEF)-funded WIO-LaB project.

The loss of biodiversity, degradation of habitats, and the modification of mangrove and coral reef ecosystems have widespread consequences. Direct human pressures on the coastal and marine environment come from increasing coastal populations, pollution and the growth of tourism. Indirect pressures come from the consequences of climate change (Climate change and development challenges in Africa) – rising sea level and high sea temperatures leading to coral bleaching. Urbanization and industrial growth, and the development of mass tourism are contributing to the loss of habitats and the degradation of living resources. Tourism development tends to be poorly controlled and is contributing to reef deterioration, pollution, inappropriate construction of sea defenses, and the loss of the natural tourism value. Population increase and migration to coastal areas are putting resources under increasing pressure, and people are resorting to practices to cater for their needs which are increasingly environmentally damaging.

Other human-related pressures come from overfishing and fishing-related damage, from urbanization and tourism development, pollution from agriculture and industry and, in Kenya, the damming of rivers for hydropower. Another key issue is the reported use of Somali shores and coastal waters as dumping grounds for hazardous wastes.

Figure 4. Management of the downstream and coastal impacts of damming in the Tana Basin, Kenya. (Source: Acreman 2005, Emerton 1994, IUCN 2003b)

Figure 4. Management of the downstream and coastal impacts of damming in the Tana Basin, Kenya. (Source: Acreman 2005, Emerton 1994, IUCN 2003b) The principal threats to the continuing health of the coral reefs come from recurrences of bleaching events similar to that of 1998, overfishing and the use of destructive gear. Another issue is the sporadic infestation of coral reefs by the invasive COTS. In the absence of efficient regulatory mechanisms and because it is an open access resource, marine fisheries often provides a refuge of last resort for impoverished coastal dwellers. In Kenya, there are indications that the degradation of reef fisheries and ecosystems has been checked or at least slowed down along those stretches of coast where MPAs have been established.

There is a lack of public and government awareness of the issues, poor enforcement of the legal framework relating to reef conservation and, in the case of Somalia, a lack of effective governance. Mangroves are also under threat. Increasing land-based pollution, decreasing freshwater discharge from rivers and overharvesting are having adverse effects on the health of mangroves – the nursery areas for many marine fish species. In Kenya, there has been overharvesting to meet an increased demand from tourism developments for construction timber, as well as mangrove clearance from the expansion of agriculture and solar salt pans. Seepage of saline groundwater from the salt pans has killed neighboring mangroves.

Damming on the Tana River in Kenya for hydropower (Figure 4) has led to a reduction in the frequency and extent of seasonal flooding events, with negative impacts on agriculture and fisheries in the lower floodplains and coastal wetlands and on the prawn fishery in the adjoining Ungwana Bay. The introduction of short-term, high-flow releases to simulate the natural flooding regime is under consideration in the design of the Mutonga-Grand Falls dam planned for the Upper Tana.

Physical shoreline change including coastal erosion is another common issue. It is caused by natural phenomena, such as the Indian Ocean tsunami of December 2004, as well as human pressures. Shoreline change impacts on tourism infrastructure and on the attractiveness of the coastal environment upon which coastal tourism largely depends. The loss of beach sands and the erosion of low-lying beach plains, much favored as sites for hotel development, are particular concerns in Kenya. In many instances, beach erosion has been exacerbated by the installation of inappropriate, hard-engineered sea defenses. Beach sand erosion also endangers the nesting sites of the sea turtle, an endangered species. It is anticipated that coastal erosion will increase with sea-level rise associated with global climate change. Shoreline accretion can also be a problem. During the last 40 years or so, changes in the regime of sediment discharge from the Sabaki River have led to major siltation and beach progradation in the vicinity of the resort town of Malindi.

The socioeconomic context of small-scale marine fisheries in Kenya

Small-scale marine fisheries in Kenya are multi-species and use multi-gear. These are economically valuable, generating in excess of US$3.2 million per year for local fishers, which would represent significantly more for the wider community if the income for traders were known. The small-scale fishers land at least 95 percent of the marine catch. It is estimated that more than 60,000 coastal people depend on these fisheries. In some coastal communities, over 70 percent of households depend on fisheries, but an estimated average for the coast as a whole is 45 percent of households. Although very few coastal households depend solely on fishing for their livelihood, many depend only on fisheries resources for income. Fishing and trading fish is one activity amongst a range of livelihood activities (both subsistence and income earning) carried out by coastal households. Fish is an important source of animal protein for coastal communities; 70 percent of fisheries-dependent households and 50 percent of non-fisheries-dependent households eat fish more than once a week. Fisheries-dependent households in Kenya are poor: this is the perception of fishers and is confirmed by food security and quality of life indicators. The high levels of dependence reflect the paucity of alternative income earning options. This situation makes coastal communities highly vulnerable to mismanagement or loss of fisheries resources. The lack of effective management, by both formal and informal institutions, and the high dependence on these resources have been identified by fisheries stakeholders as important contributors to poverty in coastal communities. The prevalence of destructive fishing gear, primarily small meshed nets, coupled with growing numbers of fishers, are key management issues to tackle.

Further reading

- Acreman, M.C., 2005. Water Resources and Environment Technical Note C.3, Environmental Flows: Flood Flows. (eds. Davis, R. and Hirji, R.), The World Bank, Washington, D.C.

- Crossland, C.J., Kremer, H.H., Lindeboom, H.J., Marshall Crossland, J.I. and Le Tissier, M.D.A., eds. 2005. Coastal Fluxes in the Anthropocene: The Land-Ocean Interactions in the Coastal Zone Project of the International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme. Global Change – the International Geosphere-Biosphere Program Series. Springer, Berlin. ISBN: 3540254501

- EIA, 2005. Country Analysis Briefs. Energy Information Administration.

- FAO Fisheries Department Homepage

- Francis, J., Nilsson, A. and Waruinge, D., 2002. Marine Protected Areas in the Eastern African Region: How Successful Are They? Ambio, 31(7-8):503-11.

- IPCC, 2001. Watson, R.T. and the Core Writing Team (eds). Climate Change 2001: Synthesis Report. A Contribution of Working Groups I, II, and III to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. ISBN: 0521807700

- IUCN, 2003. TANA RIVER, KENYA: Integrating downstream values into hydropower planning. Case Studies in Wetland Valuation, No.6, May 2003. IUCN – The World Conservation Union.

- IUCN, UNEP and ICRAN, 2004. Assessment of managed effectiveness in selected marine protected areas in the Western Indian Ocean: Final Report. IUCN – The World Conservation Union, United Nations Environment Programme and the International Coral Reef Action Network.

- Kairu, K. and Nyandwi, N. (eds. 2000). Guidelines for the Study of Shoreline Change in the Western Indian Ocean Region. IOC Manuals and Guides No. 40. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural, Paris.

- Kotb, M., et al., 2004. Status of the coral reefs in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden. In Status of Coral Reefs of the World: 2004 (ed. Wilkinson, C.), Vol. 1.

- Obura, D., et al., 2004. Status of Coral Reefs in East Africa 2004: Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique and South Africa. In Status of Coral Reefs of the World: 2004 (ed. Wilkinson, C.), Vol. 1.

- Ochiewo J., 2004. Changing fisheries practices and their socioeconomic implications in South Coast Kenya. Ocean & Coastal Management, 47(7-8):389-408.

- PERSGA/GEF, 2003. Coral Reefs in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden Surveys 1990 to 2000 Summary and Recommendations. Technical Series No. 7. The Regional Organization for the Conservation of the Environment of the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden and the Global Environment Facility, Jeddah.

- Taylor, M., Ravilious, C. and Green, E.P., 2003. Mangroves of East Africa. UNEP-WCMC Biodiversity Series No. 13.

- UNEP, 2002. Africa Environment Outlook: Past, Present and Future Perspectives. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi. ISBN: 9280721011

- UNEP, 2005. After the Tsunami: Rapid Environmental Assessment. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi.

- UNEP, 2006. Africa Environment Outlook 2

- UNEP/GPA, 2004. Shoreline Change in the Western Indian Ocean Region: An Overview. Report prepared by Western Indian Ocean Marine Science Association (WIOMSA) for United Nations Environment Programme / Global Programme of Action, The Hague.

- UNEP/GPA and WIOMSA, 2004. Regional Overview of Physical Alteration and Destruction of Habitats (PADH) in the Western Indian Ocean region. A report prepared by the Western Indian Ocean Marine Science Association for United Nations Environment Programme / Global Programme of Action, The Hague.

- UNEP-WCMC, 2000. Marine and Coastal Programme Database. United Nations Environment Programme’s World Conservation Monitoring Centre.

- UNESCO, 2005. World Heritage Centre – World Heritage List. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

- WIO-LaB, 2005. Addressing Land-based Activities in the Western Indian Ocean.

|

|

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |