Exclusive economic zone (EEZ)

Historical Background

The expressions “patrimonial sea”, “economic zone” or “exclusive economic zone” were first used in the early 1970s in regional meetings and organizations in Latin America, the Caribbean, Asia and Africa. However, the concept of an extended exclusive economic zone for economic purposes was already used in the late 40s and early 50s: it is rooted in the 1945 Truman Proclamations (on the natural resources of the subsoil and sea bed of the continental shelf and the conservation of coastal fisheries in certain areas of the high seas), the national claims of several Latin American countries (Chile and Peru), and the Santiago Declaration of 1952. The second Truman Proclamation has in particular influenced ocean-related policies in Latin American countries, especially where it states that it is appropriate for the United States "to establish conservation zones...where fishing activities have been or in the future may be developed (..)".

The 1952 Santiago Declaration. The Santiago Declaration in its preamble affirms that "governments are bound to ensure for their peoples access to necessary food supplies and to furnish them with the means of developing their economy". The declaration also affirms how the economic zone should extend no less than 200 miles from the coast. The motivation for the establishment of the zone was economic; there is anecdotal evidence that the basis for the 200-mile breadth was a map in a magazine article discussing the 1939 Panama Declaration, in which the United Kingdom and the United States agreed to establish a zone of security and neutrality around the American continents in order to prevent the re-supplying of Axis ships in South American ports. The map showed the breadth of the neutrality zone off the Chilean coast to be about 200 miles.

The 1964 European Fisheries Convention. In Europe, the economic zone, conceived more as a fisheries area, did not have the magnitude and sweep of the American equivalent. After failing to address fisheries zones in the 1958 and 1960 Geneva Conventions, the 1964 European Fisheries Convention provided among other things that each coastal State had the exclusive right to fish in a 6-mile belt measured from the baselines of its territorial sea; it also provided that in the area between the 6-mile limit and 12 miles from the baseline, other States known to have fished in that area between 1953 and 1962 had the right to continue doing so. This was an effort to reconcile th desire of coastal States to extend their jurisdiction over a greater portion of the sea and yet preserve fishing rights of other States.

The 1970 Declaration of the Latin American States on the law of the sea. This later declaration further added that the decision to extend the jurisdiction beyond the territorial sea limits is a consequence of "the dangers and damage resulting from indiscriminate and abusive practices in the extraction of marine resources" as well as the "utilization of the marine environment" giving rise to "grave dangers of contamination of the waters and disturbance of the ecological balance".

UNCLOS

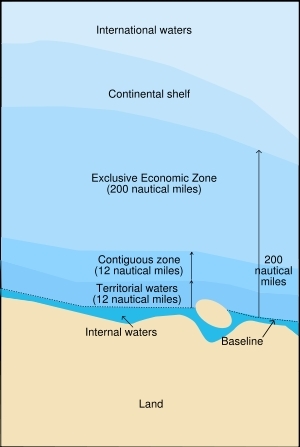

Under the United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the exclusive economic zone or EEZ is covered by Articles 56, 58 and 59. The EEZ is defined as that portion of the seas and oceans extending up to 200 nautical miles in which [[coast]al] States have the right to explore and exploit natural resources as well as to exercise jurisdiction over marine science research and environmental protection. Freedom of navigation and over flight, laying of submarine cables and pipelines, as well as other uses consented on the high seas, are still allowed.

As currently codified in UNCLOS, the EEZ marks a compromise between States seeking a 200-mile territorial sea and States wishing for more limited coastal jurisdiction.

The delimitation of EEZs between States with opposite or adjacent [[coast]s] has to be carried out through a parties agreement in accordance with international law in order to achieve – as in the words of article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice – an equitable solution. Since also in the delimitation of the continental shelf the goal is to achieve an equitable solution, many States have advocated that a single maritime boundary – valid for both the EEZ and the continental shelf – should be drawn. This provision alone has generated many delimitation disputes brought before the International Court of Justice. In the Jan Mayen Maritime Delimitation (Denmark v. Norway) case, the International Court of Justice declared that, absent a special agreement of the parties asking the Court to use a single maritime boundary applicable to both the continental shelf and the EEZ, separate boundaries must be drawn.

At this time, 104 signatories to the UNCLOS have declared a 200-mile EEZ.

Further Reading

- Attard D.J. 1986. The Exclusive Economic Zone in International Law. Oxford University Press, Oxford. ISBN: 0198256825

- Kwiatowska B. 1989. The 200 Mile Exclusive Economic Zone in the New Law of the Sea. Springer, Dordrecht. ISBN: 0792300742

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (full text)