Invasive alien species in Africa: Developing effective responses

Contents

- 1 Introduction Box 1: Key facts (Source: IUCN/SSG/ISSG 2004, Howard and Matindi 2003, McNeely and others 2001, MA 2006) Although Africa has recognized the problems associated with invasive alien species (IAS) for several decades, a comprehensive approach to IAS is still to be developed. However, as discussed in Box 2, considerable progress has been made towards this with the adoption of the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) Environmental Action Plan (NEPAD-EAP). Box 2: NEPAD makes IAS a priority (Source: NEPAD 2003) Understanding the factors driving the spread of IAS and their impacts is essential to developing effective responses. Where species have become invasive they are an important factor in environmental change, contributing to or exacerbating human vulnerability, and in some cases foreclosing livelihood and development options. Globalization – with its expanding trade and increased human movement – is likely to increase the risk of IAS. The inadvertent ending of millions of years of biological isolation has created major ongoing problems that affect both developed and developing countries. Given that the threat posed by IAS stems from transnational processes, responses need to be based on collaborative measures. Further, the potential severity of IAS needs to be acknowledged; this includes its impacts on socioeconomic systems as well as the costs of eradication. On the basis of a global assessment, the MA found that climate change (Invasive alien species in Africa: Developing effective responses) and the introduction of IAS are the two drivers of environmental change that are the most difficult to reverse.

- 2 Making choices

- 3 Building partnerships

- 4 Investing in research and capacity

- 5 Regional and global cooperation

- 6 Biosafety, sanitary and phytosanitary measures

- 7 Further reading

Introduction Box 1: Key facts (Source: IUCN/SSG/ISSG 2004, Howard and Matindi 2003, McNeely and others 2001, MA 2006) Although Africa has recognized the problems associated with invasive alien species (IAS) for several decades, a comprehensive approach to IAS is still to be developed. However, as discussed in Box 2, considerable progress has been made towards this with the adoption of the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) Environmental Action Plan (NEPAD-EAP). Box 2: NEPAD makes IAS a priority (Source: NEPAD 2003) Understanding the factors driving the spread of IAS and their impacts is essential to developing effective responses. Where species have become invasive they are an important factor in environmental change, contributing to or exacerbating human vulnerability, and in some cases foreclosing livelihood and development options. Globalization – with its expanding trade and increased human movement – is likely to increase the risk of IAS. The inadvertent ending of millions of years of biological isolation has created major ongoing problems that affect both developed and developing countries. Given that the threat posed by IAS stems from transnational processes, responses need to be based on collaborative measures. Further, the potential severity of IAS needs to be acknowledged; this includes its impacts on socioeconomic systems as well as the costs of eradication. On the basis of a global assessment, the MA found that climate change (Invasive alien species in Africa: Developing effective responses) and the introduction of IAS are the two drivers of environmental change that are the most difficult to reverse.

The threats of IAS cannot be treated in isolation. They are part of a complex set of pressures and drivers of biodiversity loss and environmental change. As discussed in The Human Dimension of Development in Africa, social, political and economic drivers are growing in both scale and scope. The underlying causes are a complex tangle, rooted both in our expanding demands on the planet and the unfair ways that we share our resources. Rising individual consumption and material expectations, especially in rich nations, are driving agricultural intensification, habitat destruction and overexploitation elsewhere. Poverty, along with inequity, particularly in trade, access to technology, and the distribution of benefits from the use of biodiversity, make sustainable use and development particularly challenging for developing countries (WRI and others 2005). Therefore, responses need to go beyond short-term crisis-focused approaches. They need to be at multiple levels, and in many incidences an interlinkages approach – which takes into account the horizontal linkages between environmental sectors as well as the links between development and social objectives – will need to be adopted. Policies across different sectors as well as at different scales, including the national and regional, will need to be harmonized. Interlinkages: environment and policy web in Africa considers this approach to decision making and responses more fully.

Traditionally, environmental law has focused on protected areas and species protection, and it has failed to take into account the multiple drivers affecting the environment, and consequently environmental protection has been insufficient. Developing an effective legal framework demands adopting appropriate measures at multiple scales: in the case of IAS this may include, among others, having more effective customs controls, appropriate trade measures, and sanitary and phytosanitary provisions for imports and transportation vessels. Legal and policy approaches to IAS need to be at multiple levels, from the local, to national, to regional, to global, and law at these different levels needs to be harmonized. Policies and laws across different sectors, such as trade and environment, need to reinforce overall social priorities and not pull in different directions.

IAS are a constant and potential threat, and thus require strategic policy responses and action.

Making choices

A woman holds a huge Nile perch skeleton, Kisumu, Lake Victoria, Kenya.

A woman holds a huge Nile perch skeleton, Kisumu, Lake Victoria, Kenya.(Source: T. Bolstad/Still Pictures)

It is important that an informed approach be taken to new introductions of IAS as well as to decisions related to existing ones. Policy and decision-making processes that evaluate the various benefits and risks associated with IAS need to be adopted. (Box 6, for example, looks at the benefits and costs of the black wattle tree). Interlinkages: the environment and policy web in Africa considers the opportunities offered by interlinking policies as well as the use of management tools that integrate development and environmental considerations. Among these are environmental impact assessments (EIAs) and valuation techniques. Genetically modified crops in Africa assesses the value of risk assessment processes that effectively link uncertainty, scientific knowledge, and social and economic objectives. It considers the opportunities of inclusive policy processes that draw on a wide range of expertise and values. Given the central role that the general public, and in particular the business sector, plays in the proliferation of IAS, this is perhaps an important tool for decision making related to IAS.

Building partnerships

Managing and controlling IAS presents special challenges. The public are particularly important partners because of their role in introducing and maintaining IAS. Many introductions occur because the importer or user is unaware of the environmental, social and economic costs of a given species and thus information and its effective communication are critical. Even where there is an appreciation of these costs, many IAS are maintained because the public do not identify them as such or see them as a threat. This is particularly true of ornamental plants, exotic pets and economically valuable species which have been used over long periods. Bringing in the public and the business sector as partners must be a cornerstone of any effective IAS policy.

Investing in research and capacity

It is widely acknowledged that good information and understanding is the basis for sound policy and management. While considerable knowledge exists about IAS, there are still many gaps. Some of these gaps relate to the impacts of specific species on other species and ecosystems, while others relate to management strategies. For example, while we know that Suncus murinus (the Asian musk shrew or house shrew) is a rapid colonizer and a growing ecological threat, preying on or competing with many animal species and that it has a large and expanding range in Africa, very little research has been carried out on how to effectively manage the species.

It is critical for Africa to invest in and to cooperate in building better understanding and capacity to deal with these and other management challenges. This involves, as discussed in Interlinkages: environment and policy web in Africa, empowering institutions and people. Direct investment in research and technical agencies is an important aspect of this, as is the development of good institutional and governance systems.

Investment in management is essential – and this too needs to be at multiple levels. Different management techniques are needed for new and established IAS. Techniques that focus on the eradication of specific species need to be complemented by more integrated approaches to ecosystem management. For example, integrated water resource management (IWRM) can complement chemical, biological and manual eradication. Management needs to be closely linked to monitoring and evaluation and adapted accordingly.

Regional and global cooperation

Given that IAS are essentially related to trade and human mobility, it is essential to improve regional and global cooperation. The NEPAD-EAP sets the basis for such cooperation in Africa. The opportunities it presents are complemented by the development of sub-regional organizations throughout Africa which focus on harmonizing trade, customs and immigration policies and practices. These institutional arrangements are discussed in the Human dimension of development in Africa.

These specific African initiatives are complemented by various global responses, in which Africa and other developing regions have played an important role. There is a gamut of different agreements dealing with different aspects of IAS that are relevant in terms of controlling their movement and possible invasive nature. These range from the multidimensional CBD, to the conservation framework of MEAs concerned with migratory species and the aquatic environment, to biosafety laws, to sanitary and phytosanitary measures, to transport, and to trade.

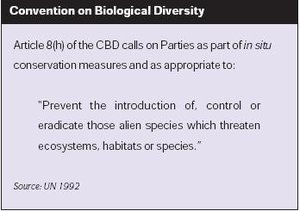

Since 1992, the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) along with Agenda 21 has set the general global framework for addressing the problems associated with IAS. The CBD recognizes the need for conservation and development as well as the close relation between them. The approach of the CBD is based on Article 8(h) of the Convention (see Box 3), and encompasses all IAS which threaten biodiversity, whether or not they remain under human control. Under this broad definition, alien plantations may also be considered to fall within the ambit of the Convention. The CBD provides the basis for taking preventative and mitigation measures to address the full range of threats posed by IAS to genetic diversity, species diversity, ecosystems and habitats.

Through the CBD Conference of the Parties (COP), a comprehensive framework for addressing these problems has been developed. The CBD has developed a sequenced approach to managing IAS. At the 2000 Conference of the Parties (COP), parties agreed:

- To give priority to preventing entry of IAS within and between states; and

- Where entry has already taken place to prevent the establishment and spread of such species.

The COP identified the eradication of such invasives as the preferred response and, where this is not feasible, the adoption of cost-effective, containment and control measures. This approach is echoed in MEAs for protecting migratory species, as well as those concerned with coastal and marine environments, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, the Ramsar Convention and the Convention on the Law of Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses.

Aquatic environments may be extremely vulnerable to IAS and eradication of such species more difficult than in terrestrial habitats. Consequently, there has been a strong focus in multilateral law on preventative measures for marine and coastal environments.

In the management of IAS, partnerships between different sectors and disciplines, as well as between the public and private sectors, is acknowledged as important. The Global Invasive Species Programme (GISP) is an initiative closely linked to the CBD and is a partnership which seeks to build global cooperation. It brings together several international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), such as World Conservation Union (IUCN) and the Nature Conservancy, scientists including those from IUCN’s Invasive Species Specialist Group, DIVERSITAS and its International Programme of Biodiversity Science, Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, South Africa’s National Botanical Institute, local projects involved in IAS eradication and control such as Working for Water in South Africa, and the United Nations Environment Programme.

The GISP has proposed 10 strategic responses to control IAS; these are (IUCN 2001):

- Building management capacity at national and international levels;

- Building research capacity using cross-sectoral and multidisciplinary approaches;

- Sharing information to, among other reasons, alert management agencies to potential dangers of new introductions;

- Developing economic policies and tools;

- Strengthening national, regional and international legal and institutional frameworks;

- Instituting a system of environmental risk analysis;

- Building public awareness and engagement;

- Preparing national strategies and plans;

- Building IAS issues into global change initiatives; and

- Promoting international cooperation.

Biosafety, sanitary and phytosanitary measures

Africa has, over a long period, recognized the importance of controlling the introduction of alien species that can be potentially damaging to ecosystem:

- The African Convention on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, adopted in 1968, requires Parties to prohibit the entry of “zoological or biological specimens, whether indigenous or imported, wild or domestic” that may cause harm to protected areas.

- The Protocol concerning Protected Areas and Wild Fauna and Flora in the East Africa Region (1985) calls for the adoption of appropriate measures to prohibit the intentional or accidental introduction of alien or new species which may cause significant or harmful changes to the sub-region.

- Other protocols developed by sub-regional bodies also address some aspects of controlling IAS. Examples include the treaty for the Establishment of the Eastern African Community (EAC), the treaty of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the treaty establishing the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA).

The African Convention on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (ACCNNR) – which revised the 1968 convention and was adopted in 2003 – requires parties to strictly control the intentional and accidental introduction of alien species, including modified organisms and to endeavour to eradicate those already introduced where their consequences are detrimental to native species or to the environment in general.

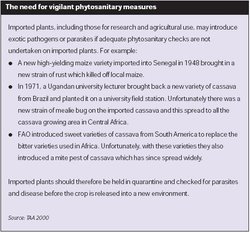

Sanitary and phytosanitary measures focus primarily on import and export regimes and provide for quarantine periods to ascertain safety as well as for the destruction of specimens. Relevant instruments and institutions include:

- The World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Health Regulations;

- The International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC);

- The World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures; and

- The Inter-African Phytosanitary Council, which was established in 1954.

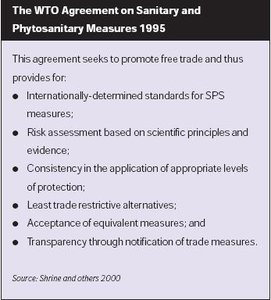

Under the IPPC, special measures have been adopted for the importation and release of alien biological control agents. However, with globalization, and the legal dominance of the WTO, managing these threats in a way that is compatible with environmental concerns, national interests and unfettered or free global trade is an increasingly complex challenge. The WTO has 148 members and creates a binding, and enforceable, set of rules designed to ensure that governments extend free market access to each others’ products and services. Box 4 sets out the essential aspects of the WTO approach.

However, as IUCN has noted: “Customs and quarantine practices, developed in an earlier time to guard against human and economic diseases and pests, are often inadequate safeguards against species that threaten native biodiversity”. New challenges include addressing the relationship between environmental change and trade, as well as growing problems of uncertainty.

Important lessons can be learnt from the legal regime developed to deal with the impact living modified organisms (LMOs) will have on biodiversity, ecosystems and human health, livelihood systems and development opportunities, as these organisms present many of the same challenges. Sanitary and phytosanitary measures historically have focused on protecting people, plants and animals from pests and diseases. However, the challenge of IAS goes beyond this to include uncertainty about possible impacts and potential conflicts between environmental, social and economic concerns.

The Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety, which entered into force in 2003, sets out the first comprehensive regulatory system for ensuring the safe transfer, handling and use of LMOs. The focus is on regulating the movement of such organisms across national borders. It is concerned with both intentional environmental introductions and LMOs that are to be used as food or feed, and for processing. Such organisms are also alien species and currently the extent to which these will threaten biological diversity, ecosystem and habitats is poorly understood – much remains uncertain and there are fundamental areas of ignorance and gaps in knowledge. In addressing this, the Protocol:

- Adopts a precautionary approach; and

- Establishes an advanced informed agreement system.

These approaches could be replicated to deal with IAS more widely, and are increasingly recognized as key components of a response strategy. The essence of this approach lies in the right to notification and prior informed consent. It includes the right to undertake risk assessment and to refuse entry of organisms due to their biological, environmental and socioeconomic impact or due to insufficient information. The African Union (AU) has developed a regime for biosafety in its Protocol on Safety in Biotechnology based on these principles. This and how to develop responses to deal effectively with scientific uncertainty are considered more fully in Genetically modified crops in Africa.

Further reading

- AU, 2003. African Convention on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. African Union, Addis Ababa.

- BirdLife International, 2004. Threatened Birds of the World 2004. BirdLife International, CD-ROM, Cambridge.

- IUCN/SSC/ISSG, 2000. IUCN Guidelines for the Prevention of Biodiversity Loss Caused by Alien Invasive Species. IUCN – the World Conservation Union Species Survival Commission, Invasive Species Specialist Group.

- IUCN/SSC/ISSG, 2004. Global Invasive Species database. IUCN – the World Conservation Union Species Survival Commission, Invasive Species Specialist Group.

- MA, 2006. Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Current State and Trends. Volume 1. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Island Press, Washington.

- McNeeley, J. A., Mooney, H. A., Neville, L. E., Schei, P. and Waage, J.K., 2001. Global Strategy on Invasive Alien Species. IUCN – the World Conservation Union, Gland.

- Shrine, C., Williams, N., and Gundling, L., 2000. A Guide to Designing Legal and Institutional Frameworks on Alien Invasive Species. IUCN –the World Conservation Union, Gland.

- UNEP, 2004. Invasive aliens threaten biodiversity and increase vulnerability in Africa. Call to Action 1(1). United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi.

- UNEP, 2006. Africa Environment Outlook 2.

- WRI in collaboration with UNEP, UNDP and the World Bank, 2005. World Resources 2005: The Wealth of the Poor – Managing Ecosystems to Fight Poverty. World Resources Institute in collaboration with the United Nations Environment Programme, the United Nations Development Programme and the World Bank.World Resources Series.World Resources Institute,Washington, D.C.

|

|

| Disclaimer: This article is taken wholly from, or contains information that was originally published by, the United Nations Environment Programme. Topic editors and authors for the Encyclopedia of Earth may have edited its content or added new information. The use of information from the United Nations Environment Programme should not be construed as support for or endorsement by that organization for any new information added by EoE personnel, or for any editing of the original content. |