Capitalism 3.0: Chapter 7 (About the EoE)

Contents

Capitalism 3.0: Chapter 7

| Topics: |

Universal Birthrights

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

—U.S.Declaration of Independence,1776

Capitalism and community aren’t natural allies. Capitalism’s emphasis on individual acquisition and consumption is usually antithetical to the needs of community. Where capitalism is about the pursuit of self-interest, community is about connecting to—and at times assisting—others. It’s driven not by monetary gain but by caring, giving, and sharing.

While the opportunity to advance one’s self-interest is essential to happiness, so too is community. No person is an island, and no one can truly attain happiness without connection to others. This raises the question of how to promote community. One view is that community can’t be promoted; it either arises spontaneously or it doesn’t. Another view is that community can be strengthened through public schools, farmers’ markets, charitable gifts, and the like. It’s rarely imagined that community can be built into our economic operating system. In this chapter I show how it can be—if our operating system includes a healthy commons sector.

The Rules of the Game

The perennially popular board game Monopoly is a reasonable simulacrum of capitalism. At the beginning of the game, players move around a commons and try to privatize as much as they can. The player who privatizes the most invariably wins.

But Monopoly has two features currently lacking in American capitalism: all players start with the same amount of capital, and all receive $200 each time they circle the board. Absent these features, the game would lack fairness and excitement, and few would choose to play it.

Imagine, for example, a twenty-player version of Monopoly in which one player starts with half the property. The player with half the property would win almost every time, and other players would fold almost immediately. Yet that, in a nutshell, is U.S. capitalism today: the top 5 percent of the population owns more property than the remaining 95 percent.

Now imagine, if you will, a set of rules for capitalism closer to the actual rules of Monopoly. In this version, every player receives, not an equal amount of start-up capital, but enough to choose among several decent careers. Every player also receives dividends once a year, and simple, affordable health insurance. This version of capitalism produces more happiness for more people than our current version, without ruining the game in any way. Indeed, by reducing lopsided starting conditions and relieving employers of health insurance costs, it makes our economy more competitive and productive.

If you doubt the preceding proposition, consider the economic operating systems of professional baseball, football, and basketball. Each league shifts money from the richest teams to the poorest, and gives losing teams first crack at new players. Even George Will, the conservative columnist, sees the logic in this: “The aim is not to guarantee teams equal revenues, but revenues sufficient to give each team periodic chances of winning if each uses its revenues intelligently.” Absent such revenue sharing, Will explains, teams in twenty of the thirty major-league cities would have no chance of winning, fans would drift away, and even the wealthy teams would suffer. Too much inequality, in other words, is bad for everyone.

The Idea of Birthrights

John Locke’s response to royalty’s claim of divine right was the idea of everyone’s inherent right to life, liberty, and property. Thomas Jefferson, in drafting America’s Declaration of Independence, changed Locke’s trinity to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. These, Jefferson and his collaborators agreed, are gifts from the creator that can’t be taken away. Put slightly differently, they’re universal birthrights.

The Constitution and its amendments added meat to these elegant bones. They guaranteed such birthrights as free speech, due process, habeas corpus, speedy public trials, and secure homes and property. Wisely, the Ninth Amendment affirmed that “the enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.” In that spirit, others have since been added.

If we were to analyze the expansion of American birthrights, we’d see a series of waves. The first wave consisted of rights against the state. The second included rights against unequal treatment based on race, nationality, gender, or sexual orientation. The third wave—which, historically speaking, is just beginning—consists of rights not against things, but for things—free public education, collective bargaining for wages, security in old age. They can be thought of as rights necessary for the pursuit of happiness.

What makes this latest wave of birthrights strengthen community is their universality. If some Americans could enjoy free public education while others couldn’t, the resulting inequities would divide rather than unite us as a nation. The universality of these rights puts everyone in the same boat. It spreads risk, responsibility, opportunity, and reward across race, gender, economic classes, and generations. It makes us a nation rather than a collection of isolated individuals.

Universality is also what distinguishes the commons sector from the corporate sector. The starting condition for the corporate sector, as we’ve seen, is that the top 5 percent owns more shares than everyone else. The starting condition for the commons sector, by contrast, is one person, one share.

The standard argument against third wave universal birthrights is that, while they might be nice in theory, in practice they are too expensive. They impose an unbearable burden on “the economy”—that is, on the winners in unfettered markets. Much better, therefore, to let everyone—including poor children and the sick—fend for themselves. In fact, the opposite is often true: universal birthrights, as we’ll see, can be cheaper and more efficient than individual acquisition. Moreover, they are always fairer.

How far we might go down the path of extending universal birthrights is anyone’s guess, but we’re now at the point where, economically speaking, we can afford to go farther. Without great difficulty, we could add three birthrights to our economic operating system: one would pay everyone a regular dividend, the second would give every child a start-up stake, and the third would reduce and share medical costs. Whether we add these birthrights or not isn’t a matter of economic ability, but of attitude and politics.

Why attitude? Americans suffer from a number of confusions. We think it’s “wrong” to give people “something for nothing,” despite the fact that corporations take common wealth for nothing all the time. We believe the poor are poor and the rich are rich because they deserve to be, but don’t consider that millions of Americans work two or three jobs and still can’t make ends meet. Plus, we think tinkering with the “natural” distribution of income is “socialism,” or “big government,” or some other manifestation of evil, despite the fact that our current distribution of income isn’t “natural” at all, but rigged from the get-go by maldistributed property.

The late John Rawls, one of America’s leading philosophers, distinguished between predistribution of property and redistribution of income. Under income redistribution, money is taken from “winners” and transferred to “losers.” Understandably, this isn’t popular with winners, who tend to control government and the media. Under property predistribution, by contrast, the playing field is leveled by spreading property ownership before income is generated. After that, there’s no need for income redistribution; property itself distributes income to all. According to Rawls, while income redistribution creates dependency, property predistribution empowers.

But how can we spread property ownership without taking property from some and giving it to others? The answer lies in the commons—wealth that already belongs to everyone. By propertizing (without privatizing) some of that wealth, we can make everyone a property owner.

What’s interesting is that, for purely ecological reasons, we need to propertize (without privatizing) some natural wealth now. This twenty-first century necessity means we have a chance to save the planet, and as a bonus, add a universal birthright.

Dividends from Common Assets

A cushion of reliable income is a wonderful thing. It can be saved for rainy days or used to pursue happiness on sunny days. It can encourage people to take risks, care for friends and relatives, or volunteer for community service. For low-income families, it can pay for basic necessities.

Conversely, the absence of reliable income is a terrible thing. It heightens anxiety and fear. It diminishes our ability to cope with crises and transitions. It traps many families on the knife’s edge of poverty, and makes it harder for the poor to rise.

So why don’t we, as Monopoly does, pay everyone some regular income—not through redistribution of income, but through predistribution of common property? One state—Alaska—already does this. As noted earlier, the Alaska Permanent Fund uses revenue from state oil leases to invest in stocks, bonds, and similar assets, and from those investments pays yearly dividends to every resident. Alaska’s model can be extended to any state or nation, whether or not they have oil. We could, for instance, have an American Permanent Fund that pays equal dividends to long-term residents of all 50 states. The reason is, we jointly own many valuable assets.

Recall our discussion about common property trusts. These trusts could crank down pollution and earn money from selling ever-scarcer pollution permits. The scarcer the permits get, the higher their prices would go. Less pollution would equal more revenue. Over time, trillions of dollars could flow into an American Permanent Fund.

What could we do with that common income? In Alaska the deal with oil revenue is 75 percent to government and 25 percent to citizens. For an American Permanent Fund, I’d favor a 50/50 split, because paying dividends to citizens is so important. Also, when scarce ecosystems are priced above zero, the cost of living will go up and people will need compensation; this wasn’t, and isn’t, the case in Alaska. I’d also favor earmarking the government’s dollars for specific public goods, rather than tossing them into the general treasury. This not only ensures identifiable public benefits; it also creates constituencies who’ll defend the revenue sharing system.

Waste absorption isn’t the only common resource an American Permanent Fund could tap. Consider also, the substantial contribution society makes to stock market values. As noted earlier, private corporations can inflate their value dramatically by selling shares on a regulated stock exchange. The extra value derives from the enlarged market of investors who can now buy the corporation’s shares. Given a total stock market valuation of about $15 trillion, this socially created liquidity premium is worth roughly $5 trillion.

At the moment, this $5 trillion gift flows mostly to the 5 percent of the population that own more than half the private wealth. But if we wanted to, we could spread it around. We could do that by charging corporations for using the public trading system, just as investment bankers do. (For those of you who haven’t been involved in a public stock offering, investment bankers are like fancy doormen to a free palace. While the public charges almost nothing to use the capital markets, investment bankers exact hefty fees.)

The public’s fee could be in cash or stock. Let’s say we required publicly traded companies to deposit 1 percent of their shares each year in the American Permanent Fund for ten years—reaching a total of 10 percent of their shares. This would be our price not just for using a regulated stock exchange, but also for all the other privileges (limited liability, perpetual life, copyrights and patents, and so on) that we currently bestow on private corporations for free.

In due time, the American Permanent Fund would have a diversified portfolio worth several trillion dollars. Like its Alaskan counterpart, it would pay equal yearly dividends to everyone. As the stock market rose and fell, so would everyone’s dividend checks. A rising tide would lift all boats. America would truly be an “ownership society.”

A Children’s Opportunity Trust

Not long ago, while researching historic documents for this book, I stumbled across this sentence in the Northwest Ordinance of 1787: “[T]he estates, both of resident and nonresident proprietors in the said territory, dying intestate, shall descent to, and be distributed among their children, and the descendants of a deceased child, in equal parts.”What, I wondered, was this about?

The answer, I soon learned, was primogeniture—or more precisely, ending primogeniture in America. Jefferson, Madison, and other early settlers believed the feudal practice of passing all or most property from father to eldest son had no place in the New World. This wasn’t about equal rights for women; that notion didn’t arise until later. Rather, it was about leveling the economic playing and avoiding a permanent aristocracy.

A nation in which everyone owned some property—in those days, this meant land—was what Jefferson and his contemporaries had in mind. In such a society, hard work and merit would be rewarded, while inherited privilege would be curbed. This vision of America wasn’t wild romanticism; it seemed quite achievable at the time, given the vast western frontier. What thwarted it, later, were giveaways of land to speculators and railroads, the rise of monopolies, and the colossal untaxed fortunes of the robber barons.

Fast-forward to the twenty-first century. Land is no longer the basis for most wealth; stock ownership is. But Jefferson’s vision of an ownership society is still achievable. The means for achieving it lies not, as George W. Bush has misleadingly argued, in the privatization of Social Security and health insurance, but in guaranteeing an inheritance to every child. In a country as super-affluent as ours, there’s absolutely no reason why we can’t do that. (In fact, Great Britain has already done it. Every British child born after 2002 gets a trust fund seeded by $440 from the government—$880 for children in the poorest 40 percent of families. All interest earned by the trust funds is tax-free.)

Let me get personal for a minute. My parents weren’t wealthy; both were children of penniless immigrants. They worked hard, saved, and invested—and paid my full tuition at Harvard. Later, they helped me buy a home and start a business. Without their financial assistance, I wouldn’t have achieved the success that I have. I, in turn, have set up trust funds for my two sons. As I did, they’ll have money for college educations, buying their own homes, and if they choose, starting their own businesses—in other words, what they need to get ahead in a capitalist system.

As I hope my sons will be, I’m extremely grateful for my economic good fortune. At the same time, I’m painfully aware that my family’s good fortune is far from universal. Many second-, third-, and even seventh-generation Americans have little or no savings to pass on to their heirs. Their children may receive their parents’ love and tutelage, but they don’t get the cash needed nowadays for a first-rate education, a down payment on a house, or a business venture. A few may rise because of extraordinary talent and luck, but the majority will spend their lives on a treadmill, paying bills and perhaps tucking a little away for old age. Their sons and daughters, in turn, will face a similar future.

It doesn’t have to be this way. One can imagine all sorts of government programs that can help people advance in life—free college and graduate school, GI bills, housing subsidies, and so on. Such programs, as we know, come and go, and I prefer more rather than less of them. But the simplest way to help people advance is to give them what my parents gave me, and what I’m giving my sons: a cash inheritance. And the surest way to do that is to build such inheritances into our economic operating system, much the way Social Security is.

When Jefferson substituted pursuit of happiness for Locke’s property, he wasn’t denigrating the importance of property. Without presuming to read his mind, I assume he altered Locke’s wording to make the point that property isn’t an end in itself, but merely a means to the higher end of happiness. In fact, the importance he and other Founders placed on property can be seen throughout the Constitution and its early amendments. Happiness, they evidently thought, may be the ultimate goal, but property is darn useful in the pursuit of it.

If this was true in the eighteenth century, it’s even truer in the twenty-first. The unalienable right to pursue happiness is fairly meaningless under capitalism without a chunk of capital to get started. And while Social Security provides a cushion for the back end of life, it does nothing for the front end. That’s where we need something new.

A kitty for the front end of life has to be financed differently than Social Security because children can’t contribute in advance to their own inheritances. But the same principle of intergenerational solidarity can apply. Consider an intergenerational transfer fund through which departing souls leave money not just for their own children, but for all children. This could replace the current inheritance tax, which is under assault in any case. (As this is written, Congress has temporarily phased out the inheritance tax as of 2010; a move is afoot to make the phaseout permanent.) Mind you, I think ending the inheritance tax is a terrible idea; it’s the least distorting (in the sense of discouraging economic activity) and most progressive tax possible. It also seems sadly ironic that a nation that began by abolishing primogeniture is now on the verge of creating a permanent aristocracy of wealth. That said, if the inheritance tax is eliminated, an intergenerational transfer fund would be a fitting substitute.

The basic idea is similar to the revenue recycling system of professional sports. Winners—that is, millionaires and billionaires—would put money into a kitty (call it the Children’s Opportunity Trust), to be divided among all children equally, so the next round of economic play can be more competitive. In this case, the winners will have had a lifetime to enjoy their wealth, rather than just a single season. When they depart, half their estates, say, could be passed to their own children, while the other half would be distributed among all children. Their own offspring would still start on third base, but others would at least be in the game.

Under this plan, no money would go to the government. Instead, every penny would go back into the market, through the bank or brokerage accounts (managed by parents) of newborn children. I’d call these new accounts Individual Inheritance Accounts; they’d be front-of-life counterparts of Individual Retirement Accounts. After children turn eighteen, they could withdraw from their accounts for further education, a first home purchase, or to start a business.

Yes, contributions to the Children’s Opportunity Trust would be mandatory, at least for estates over a certain size (say $1 or $2 million). But such end-of-life gifts to society are entirely appropriate, given that so much of a millionaire’s wealth is, in reality, a gift from society. No one has expressed this better than Bill Gates Sr., father of the world’s richest person. “We live in a place which is orderly. It’s a place where markets work because there’s legal structure to support them. It’s a place where people can own property and protect it. People who have the good fortune, the skill, the luck to become wealthy in our country, simply have a debt to the source of their opportunity.”

I like the link between end-of-life recycling and start-of-life inheritances because it so nicely connects the passing of one generation with the coming of another. It also connects those who have received much from society with those who have received little; there’s justice as well as symmetry in that.

To top things off, I like to think that the contributors—millionaires and billionaires all—will feel less resentful about repaying their debts to society if their repayments go directly to children, rather than to the Internal Revenue Service. They might think of the Children’s Opportunity Trust as a kind of venture capital fund that makes start-up investments in American children. A venture capital fund assumes nine out of ten investments won’t pay back, but the tenth will pay back in spades, more than compensating for the losers. So with the Children’s Opportunity Trust. If one out of ten children eventually departs this world with an estate large enough to “pay back” in spades the initial investment, then the trust will have earned its keep. And who knows? Some of those paying back might even feel good about it.

Health Risk Sharing

Pooled risk sharing, or social insurance, has several advantages over individualized risk. One is universality: everyone is covered and assured a dignified existence. Another is fairness: when risks are individualized, some people fare well, but others do not. There are winners and losers, and the disparities can be great.

Social insurance principles have been applied in America to the risks of old-age poverty, temporary unemployment, and disability. In every other capitalist democracy, they’ve been applied to these risks and ill health. The United States provides universal health insurance only to people age sixty-five and older. Extending this coverage to all Americans would be another pillar of the commons sector and make us more of a national community.

For the benefit of U.S. readers, it’s worth describing how universal health insurance works. Take our northern neighbor as a case in point. In 1984, the Canadian Parliament unanimously passed the Canada Health Act, designed to ensure that all residents of Canada have access to necessary hospital and physician services on a prepaid basis. Each province now runs its own insurance program in accordance with five federal principles:

- Universal. All residents are covered.

- Comprehensive. All medically necessary services are covered.

- Not-for-profit. Each provincial plan is not-for-profit.

- Accessible. Premiums are affordable or subsidized.

- Portable. Coverage continues when a person travels.

The act also bans extra billing by medical practitioners. As a result, the system is incredibly simple. For routine doctor visits, Canadians need only present their health card. There are no forms to fill out or bills to pay. The system is financed by a combination of federal and provincial funds. The provinces raise part of their funds by charging monthly premiums.

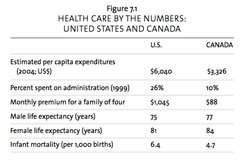

I compared monthly premiums in 2005 for families of four in California (through Aetna) and in British Columbia (through the provincial health plan). For the California family, the rate was $1,045 when the head of household is age forty-five; for the Canadian family, the rate was $88 no matter what the age of the parents (see figure 7.1). Discounts are available to low-income families.

It’s important to note that in Canada, unlike Britain, there’s no National Health Service. Medical providers work for themselves, or for private clinics and hospitals. Customers can freely choose their doctors, hospitals, and other practitioners. The only thing that’s been added to the commons is the risk-sharing system.

Here’s the bottom line. All Canadians get health care and peace of mind at a per capita cost that’s about 45 percent lower than ours. Canada lays out less than ten cents of every health care dollar on administration, while we spend nearly thirty cents (and that doesn’t include the time and energy patients themselves spend on paper-work). What’s more, our health care system doesn’t even keep us healthy. Our infant mortality rate is higher than Canada’s, our life expectancy is lower, and we have proportionally more obesity, cancer, diabetes, and depression. To top it off, forty-five million of us have no health insurance at all.

What can we learn from this comparison? Social insurance enables members of a community to reduce common risks more cheaply and efficiently than private insurance does. It’s thus a vital piece of social infrastructure. This is especially so when we want coverage to be universal. Some of the savings result from economies of scale and low marketing and administrative costs. Others result from simplicity and the absence of profit.

Notes

- “The aim is not to guarantee . . .”: George Will, “Field of Dollars,” Washington Post, Feb. 28, 1999, p. B7.redistribution vs. pre distribution: John Rawls, A Theory of Justice (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1971).Less pollution = more revenue: At this moment, the federal government and several states are giving corporate polluters free rights to use the atmosphere. It may seem shocking that politicians would create new property rights from a shared inheritance and give these valuable assets to a few corporations, yet that’s what they’re doing.“[T]he estates . . .”: For text of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, see Northwest Ordinance. (Capitalism 3.0: Chapter 7) The quote is from section 2.

- interest earned by trust funds: For information about Britain’s “baby bonds,” see “Saving from Birth: Baby Bonds Are a Great Radical Idea,” The Guardian, Apr. 11, 2003. See also Stuart White (ed.), The Citizen’s Stake: Exploring the Future of Universal Asset Policies (Bristol, U.K.: Policy Press, 2006).

- weathy’s debt: Bill Gates Sr.’s quote is taken from a forum at the Urban Institute on Jan. 14, 2003, and can be found at Forum on the Estate Tax.

- per capital expenditures: Stephen Heffler, Sheila Smith, Sean Keehan, Christine Borger, M. Kent Clemens and Christopher Truffer, “U.S. Health Spending Projections for 2004–2014,” Health Affairs, Feb. 23, 2005.

- percent spent on administration: Steffie Woolhandler, Terry Campbell, and David Himmelstein, “Costs of Health Care Administration in the U.S. and Canada,” New England Journal of Medicine, Aug. 21, 2003. * life expectancy: CIA World Factbook, 2006.

- U.S. health insurance: For information on obesity, diabetes, and depression see NewsTarget.com. For data on health insurance coverage in the United States, see Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2003 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau, Aug. 2004), p. 14. . For information about health care costs in the United States, see Paul Krugman, “The Medical Money Pit,” New York Times, Apr. 15, 2005, op ed page.