Brownfield regeneration (Agricultural & Resource Economics)

Contents

- 1 Brownfield regeneration

- 1.1 What is a brownfield?

- 1.2 Extent of the problem

- 1.3 What is Sustainable Brownfield Regeneration?

- 1.3.1 Beneficial use

- 1.3.2 Satisfaction of human needs

- 1.3.3 For present and future generations

- 1.3.4 Environmentally sensitive

- 1.3.5 Economically viable

- 1.3.6 Institutionally robust

- 1.3.7 Socially acceptable

- 1.3.8 Within the particular regional context

- 1.3.9 Discussion of the definition

- 1.3.10 Citation

Brownfield regeneration

What is a brownfield?

The term ‘brownfield’ is used to refer to both known contaminated sites and those only suspected of being so because of previous land-use activities (e.g. waste disposal, manufacturing, petrol stations). Below are two examples of brownfield definitions:

- ‘Brownfields are sites that have been affected by the former uses of the site and surrounding land; are derelict or underused; have real or perceived contamination problems; are mainly in developed urban areas; and require intervention to bring them back to beneficial use.’

- ‘A brownfield site is any land or premises which has previously been used or developed and is not currently fully in use, although it may be partially occupied or utilized. It may also be vacant, derelict or contaminated. Therefore a brownfield site is not available for immediate use with intervention.’

Brownfield regeneration is attractive to communities and policymakers for three reasons:

- it reduces the conversion of agricultural land and rural sites to urban uses;

- it reduces the site’s negative impacts in the local community thus promoting economic growth; and

- it removes existing contamination problems and associated risks to human health and ecological systems.

Extent of the problem

The brownfield problem in most of the USA and Western Europe is the result of two concurrent factors: a) the numerous plant closings and downsizing experienced as economies moved away from manufacturing starting in the 1970s; and b) the passing of environmental legislation in the 1980s that held specified parties liable for the cost of cleanup at contaminated sites. More recently in the USA, state programs have been established to encourage redevelopment of the potentially contaminated brownfield sites by offering regulatory burden reductions, liability relief and/or financial support for the regeneration costs. Despite this, investors commonly shy away from potentially contaminated properties due to the high perceived costs associated with remediation. While the US Superfund (Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), United States) was first passed in 1980, the relevant legislation in most European countries is much more recent. For example, Germany’s Federal Soil Protection Act was passed in 1998, the UK’s Part IIA of the 1990 Environmental Protection Act, which upholds the ‘polluter pays’ principle and imposes liability for the mandatory remediation of contaminated land, was brought into force in 2000, while other European countries (like the Netherlands) have crafted their own ‘Superfund-like’ legislation, which includes an innocent landowner disclaimer and provisions for the municipality to take over remediation.

The issue of how to develop brownfield sites in a sustainable way is very topical and the management of brownfield sites is an important element of the sustainable development strategies of North American and European governments. In recent times stakeholder and consumer demands are increasingly driving the call for brownfield regeneration projects to be sustainable in conjunction with the momentum derived from the political forces. But this begs the questions: What is sustainable brownfield regeneration? What precisely is the best definition for sustainability in the brownfield regeneration process? And how do we know if a project ‘is sustainable’ and when do we know ‘it is not sustainable’?

What is Sustainable Brownfield Regeneration?

Many sustainability definitions currently suggest every change implies a re-distribution of resources to the disadvantage of one or another stakeholder, (i.e. harm to someone), therefore it is not a definition of true sustainability. However, it depends on whether you take the literal meaning of sustainability, or use ‘if at least one person is made better off and nobody is made worse off’ (Pareto efficiency) or ‘if those people made better off compensate those people made worse off’ (Pareto optimality) definitions instead.

The sustainability definition in the context of brownfield regeneration proposed here is:

Sustainable Brownfield Regeneration is the management, rehabilitation and return to beneficial use of the brownfields in such a manner as to ensure the attainment and continued satisfaction of human needs for present and future generations in environmentally sensitive, economically viable, institutionally robust, socially acceptable and balanced way within the particular regional context.

Some of the terms used for the definition are very broad and need some further explanation to make the stepwise definition more operable in the sustainable brownfield regeneration field.

Beneficial use

The expression “beneficial use” of brownfield land provokes the question - beneficial for whom? Benefits should be created in all sustainability dimensions (i.e. not just monetary benefits) and can be broken down into: beneficial for the environment (e.g. improved ecosystem stability), beneficial for stakeholders (e.g. in monetary terms); beneficial for the community (e.g. better living standard, development, increased social cohesion); and beneficial for sustainable institutions (e.g. fostering more efficient structures in administration, offering new opportunities of citizen participation). However, it is not just resources that should be considered, but the time dimension with regard to protecting present and future generations. Therefore, the term suggests direct and attractive benefits for all stakeholders within the affected region (owners, planners/developers, future users, neighboring communities), whilst not encouraging social disparities.

Satisfaction of human needs

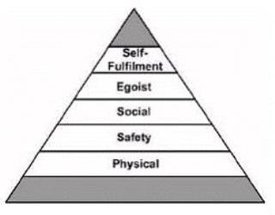

Brownfield regeneration and urban planning have to satisfy human needs to be ultimately successful. Maslow arranged human needs into a hierarchy of strength or potency, where man strives to satisfy higher needs after the lower needs have been satisfied.

Different stakeholders will have different needs within brownfield regeneration in keeping with Maslow’s theory and thus will express different expectations. For example, those people with unsatisfied security needs might look for immediate benefits (e.g. jobs, health situation) while those with unsatisfied social and esteem needs might look for social integration or prestigious roles in the redevelopment process.

For present and future generations

“Present and future generations” refers to the fact that planning and remedial action should have a short-term and a long-term view with each sustainability dimension in mind. In the brownfield context, short-term would mean a period of 2-7 years (i.e. covering a project period or an election period), whereas long-term would mean a period of 50-100 years (i.e. 3-4 generations or 1-3 brownfield utilization cycles). Planning and realization in sustainable brownfield projects should have positive effects in both the short term and the long term, but experience shows us that short-term interests (e.g. immediate provision of housing, employment, leisure) usually outweigh long-term interests. Here, the state and its institutions play an important role as stakeholders of future interests (such as natural resource reserves or ideal social structure).

However, it has to be taken into account that resources may change their relevance or value (Value theory) over time (e.g. through successful exploration, through substitute resources or due to technological development) which may result in a change to the sustainability criteria over time (i.e. the process is dynamic).

Environmentally sensitive

Brownfield regeneration is expected to happen in an environmentally sensitive manner with the wide-reaching aim of improving the region of the project in the long term. “Environmentally sensitive” means the use of renewable resources (or even non-renewable resources in the short term) in the process of brownfield regeneration and a stepwise reduction in negative environmental impacts (e.g. noise, radiation, infiltration of dangerous substances) emitting from the site. The structural diversity of the environment should be protected/improved to foster an increase in regional/local biodiversity in addition to future infrastructure/buildings being designed to facilitate simple deconstruction or easy adaptation. All measures taken should not (where possible) interfere with the targets of the other sustainability dimensions.

Economically viable

A positive cost-benefit balance is achieved for the majority of the stakeholders in the short- to medium term. This means that in the near future all social and ecological costs need to be internalized into product/service prices (e.g. emissions, social standards, effects on health, effects on environment) thus leading to a long-term productivity increase in brownfield resources. In this way, a win-win situation between economic, social and environmental targets can be achieved.

Sustainability needs a supportive, stable environment from the brownfield economy, the political system, and the affected society. For example, the region needs to provide resources like a qualified labor force, required production inputs and higher education institutions to maintain sustainable processes for brownfield regeneration.

Institutionally robust

We may think of institutions in this context as administrative-organizational structures, and not in the much broader sociological sense. For ‘institutionally robust’ brownfield regeneration, the institutional structure between and within the stakeholders’ organizations has to reflect an aspect of sustainability, with new institutions being compatible with existing frameworks (e.g. laws, scientific standards, regulations, standardized procedures) in horizontal terms (e.g. other economic sectors) as well as vertical terms (superior and inferior planning levels). The institutional design must be able to cope with short-, medium- and long-term interests and provide tools for the mediation between the different sustainability (Sustainable development triangle) dimensions. Therefore, institutions need to maintain a certain degree of flexibility in order to establish new institutions or change existing ones as a reaction to changing situations (i.e. institutional sustainability does not necessarily demand the creation of permanent, lasting institutions).

Socially acceptable

A brownfield regeneration process is socially acceptable when it meets the actual (as well as the known and expected future) needs of the communities in the region. It is fair to assume that acceptance of a project is generally higher in a socially cohesive community that is able to participate actively in the decision-making process. However, acceptance will usually be a majority affair as 100% of the people will not agree with 100% of the projects. As a general rule, acceptance will be enhanced if an overall increase in living standards and welfare as well as a distribution of benefits that reduce poverty and increase social stability and parity (i.e. in terms of income, social status, health, education, integration) is experienced. The creation of more cohesive community requires a certain degree of participation representing the minimum range of stakeholders from different fields (authorities, NGOs, associations) to make the process compatible with local and regional expectations, values and norms.

Within the particular regional context

The boundaries of the region are defined by the extension of the area that is directly or indirectly affected by the sustainable site redevelopment process, but it is also necessary that they are also administrative units of a defined scale (e.g. ward; town; county). It should be noted that a holistic, future-orientated approach that incorporates the site into a regional development concept (with the functional link between site and region being uppermost) is required. The need to have an operable definition of a region does not mean that specific regional characteristics outside the influence of brownfield regeneration are neglected, as all four dimensions of sustainability (Sustainable development triangle) are taken into consideration.

Discussion of the definition

A regenerated brownfield site can be the source of negative environmental impacts and still be sustainable, e.g. positive effects in the other dimensions of sustainability may outweigh the negative ecological ones and the negative impacts on the site are balanced on the urban/regional scale. Otherwise, in order to achieve a more sustainable situation all brownfield sites would have to be turned into greenfields! An industrial development on a brownfield site (which of course is very likely to produce negative environmental impacts) can be more sustainable than a public park, as it contributes to saving natural resources of the alternative greenfield site, generates jobs and produces positive effects in the social and economic dimension. This means a brownfield project that does not cause any negative environmental impacts overall does not necessarily need to be more sustainable than a “dirty” industrial development where potential activities and development are more sustainable in the broader regional context.

The definition needs further discussion especially with regard to some of the explanations. The wording “environmentally sensitive”, “economically viable”, “institutionally robust” and “socially acceptable” in the sustainability definition imply an approach of “first do no harm”. The four dimensions are equally ranked in the definition meaning that they a) intend not to worsen the present state and b) aim to describe an improved vision for the future. The latter would demand replacing “environmentally sensitive” with “the environmental state improving”, “economically viable” with “economically attractive / profitable”, “institutionally robust” with “fostering local and regional institutions”, and “socially acceptable” with “socially desirable”.

The definition might imply that sustainable development can be regarded as a situation that can be achieved some time in the future. However, absolute sustainability cannot be achieved, as the single dimensions of sustainability will always compete against each other to a certain extent. To reach a final situation would also contradict the principle of the sustainability concept as future generations would be dealt a fait accompli if ‘sustainability’ is set out today. Therefore, the focus should not be laid on situations regarded as optimal from today’s perspective, but allow for adaptation potential and high flexibility when considering how to approach sustainable development.