Acceleration

In physics, and more specifically kinematics, acceleration is the change in velocity over time. Because velocity is a vector, it can change in two ways: a change in magnitude and/or a change in direction.

In one dimension, i.e. a line, acceleration is the rate at which something speeds up or slows down. However, as a vector quantity, acceleration is also the rate at which direction changes. Acceleration has the dimensions LT?2.

In SI units, acceleration is measured in metres per second squared (m/s2).

In common speech, the term acceleration commonly is used for an increase in speed (the magnitude of velocity); a decrease in speed is called deceleration. In physics, a change in the direction of velocity also is an acceleration: for rotary motion, the change in direction of velocity results in centripetal (toward the center) acceleration; where as the rate of change of speed is a tangential acceleration.

In classical mechanics, for a body with constant mass, the acceleration of the body is proportional to the resultant (total) force acting on it (Newton's second law):where F is the resultant force acting on the body, m is the mass of the body, and a is its acceleration.

Contents

Average and instantaneous acceleration

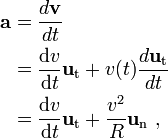

Average acceleration is the change in velocity (?v) divided by the change in time (?t). (See Figure 1.)

Instantaneous acceleration is the acceleration at a specific point in time.

Tangential and centripetal acceleration

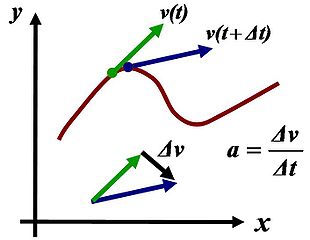

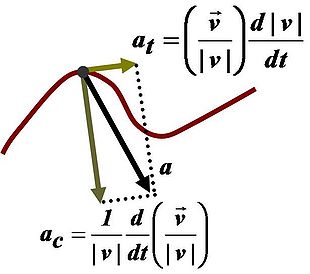

The velocity of a particle moving on a curved path as a function of time can be written as:with v(t) equal to the speed of travel along the path, and ut a unit vector tangent to the path pointing in the direction of motion at the chosen moment in time.

where un is the unit (outward) normal vector to the particle's trajectory, and Ris its instantaneous radius of curvature based upon the osculating circle at time t. These components are called thetangential acceleration at and the radial acceleration, respectively. The negative of the radial acceleration is the centripetal acceleration ac, which points inward, toward the center of curvature.(See Figure 2.)

Extension of this approach to three-dimensional space curves that cannot be contained on a planar surface leads to the Frenet-Serret formulas.

Relation to relativity

After completing his theory of special relativity, Albert Einstein realized that forces felt by objects undergoing constant proper acceleration are actually feeling themselves being accelerated, so that, for example, a car's acceleration forwards would result in the driver feeling a slight pressure between himself and his seat. In the case of gravity, which Einstein concluded is not actually a force, this is not the case; acceleration due to gravity is not felt by an object in free-fall. This was the basis for his development of general relativity, a relativistic theory of gravity.

Further Reading

- :* Crew, Henry (2008). The Principles of Mechanics. BiblioBazaar, LLC. ISBN 0559368712.

- Bondi, Hermann (1980). Relativity and Common Sense. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0486240215.

- Lehrman, Robert L. (1998). Physics the Easy Way. Barron's Educational Series. ISBN 0764102362.

- Larry C. Andrews & Ronald L. Phillips (2003). Mathematical Techniques for Engineers and Scientists. SPIE Press. ISBN 0819445061.

- Ch V Ramana Murthy & NC Srinivas (2001). Applied Mathematics. New Delhi: S. Chand & Co.. ISBN 81-219-2082-5.

Note: This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Acceleration that was accessed on April 9, 2010. The Author(s) and Topic Editor(s) associated with this article may have significantly modified the content derived from Wikipedia with original content or with content drawn from other sources. All content from Wikipedia has been reviewed and approved by those Author(s) and Topic Editor(s), and is subject to the same peer review process as other content in the EoE. The current version of the Wikipedia article may differ from the version that existed on the date of access. See the EoE’s Policy on the Use of Content from Wikipedia for more information.